The African American Experience in Historically White Fraternities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Printable Version of Entire Document (PDF)

CBCF CHAIR'S MESSAGE "AFoundation Expanding Opportunities" n he history of Black America is the history ofa people BTf who have overcome tremendous odds, triumphed over the adversity of slavery and segregation, and found opportunity in hardship. we come together for the 21st Annual Legislative Weekend, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation is rAsproud to celebrate these achievements and to help chart a course for the future that willenable us to continue to build on the successes of the past. The civil rights era inaugurated by Thurgood j^ Marshall and other champions of justice was marked by the \u25a0 passage of landmark legislation banning discrimination in employment, housing, public accommodations, and the voting booth. Thanks to this watershed period of progress in our Congressman Alan Wheat nation's recent past, an unprecedented number of Black Americans are now beginning to realize economic security. Yetrecent events have shown us that we cannot take these gains for granted. Although a vibrant and growing Black middle-class willcontinue to make headway in the 19905, a dismaying portion of our population faces a bleak future as a result of governmental indifference and neglect during the last ten years. An increasingly hostile Supreme Court has begun to chip away at the legal underpinnings of our nation's antibias safety net and the current Administration has shown itself willingto play racial politics withlegislative safeguards against discrimination. In the face of these new obstacles to progress, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation is rising to the challenge of developing strategies to address the inequities that continue to confront modern society and to create new opportunities for an increasingly diverse Black American population. -

College of Wooster Miscellaneous Materials: a Finding Tool

College of Wooster Miscellaneous Materials: A Finding Tool Denise Monbarren August 2021 Box 1 #GIVING TUESDAY Correspondence [about] #GIVINGWOODAY X-Refs. Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See also Oversized location #J20 Flyers, Pamphlets #METOO X-Refs. #ONEWOO X-Refs #SCHOLARSTRIKE Correspondence [about] #WAYNECOUNTYFAIRFORALL Clippings [about] #WOOGIVING DAY X-Refs. #WOOSTERHOMEFORALL Correspondence [about] #WOOTALKS X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location A. H. GOULD COLLECTION OF NAVAJO WEAVINGS X-Refs. A. L. I. C. E. (ALERT LOCKDOWN INFORM COUNTER EVACUATE) X-Refs. Correspondence [about] ABATE, GREG X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location ABBEY, PAUL X-Refs. ABDO, JIM X-Refs. ABDUL-JABBAR, KAREEM X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets See Oversized location Press Releases ABHIRAMI See KUMAR, DIVYA ABLE/ESOL X-Refs. ABLOVATSKI, ELIZA X-Refs. ABM INDUSTRIES X-Refs. ABOLITIONISTS X-Refs. ABORTION X-Refs. ABRAHAM LINCOLN MEMORIAL SCHOLARSHIP See also: TRUSTEES—Kendall, Paul X-Refs. Photographs (Proof sheets) [of] ABRAHAM, NEAL B. X-Refs. ABRAHAM, SPENCER X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] Flyers, Pamphlets ABRAHAMSON, EDWIN W. X-Refs. ABSMATERIALS X-Refs. Clippings [about] Press Releases Web Pages ABU AWWAD, SHADI X-Refs. Clippings [about] Correspondence [about] ABU-JAMAL, MUMIA X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets ABUSROUR, ABDELKATTAH Flyers, Pamphlets ACADEMIC AFFAIRS COMMITTEE X-Refs. ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND TENURE X-Refs. Statements ACADEMIC PROGRAMMING PLANNING COMMITTEE X-Refs. Correspondence [about] ACADEMIC STANDARDS COMMITTEE X-Refs. ACADEMIC STANDING X-Refs. ACADEMY OF AMERICAN POETRY PRIZE X-Refs. ACADEMY SINGERS X-Refs. ACCESS MEMORY Flyers, Pamphlets ACEY, TAALAM X-Refs. Flyers, Pamphlets ACKLEY, MARTY Flyers, Pamphlets ACLU Flyers, Pamphlets Web Pages ACRES, HENRY Clippings [about] ACT NOW TO STOP WAR AND END RACISM X-Refs. -

Heritage Guid E African America N

BU FFA AF LO RIC N AN IA HER G ITA A A GE M R G E A U R I IC D A E N VisitBuffaloNiagara.com C O N T Introduction..................1 E N Black Buffalo History..........2-4 T A Culture of Festivals...............5-8 S The Spoken Word Circuit...............9 Cultural Institutions......................10-13 Historic Sites & Landmarks.............14-17 Food for the Soul.............................18-19 Shopping Stops................................20-21 Houses of Worship..........................22-24 The Night Scene.................................25 Itineraries...................................26-33 Family Reunion & Group Event Planner..........34-35 References & Acknowledgements......36 African American Buffalo A Quilt of American Experience KC KRATT KC Michigan Street Baptist Church Buffalo is an heirloom quilt stitched with the tenacity and triumph of the African American spirit. The city was a final stop on the freedom train north from slavery and the Jim Crow South. In its heyday, Buffalo represented hope and self-empowerment for black Ameri- cans, and a better life for generations to come. Black frontiersman Joseph Hodges was one of Buffalo’s earliest non-white settlers. Local griots - oral historians - know that Underground Railroad conductor Harriet “Mother Moses” Tubman led bands of runaways through the Niagara region. Abolitionist William Wells Brown lived on Pine Street in Buffalo and H a rr helped fugitives cross the water into Canada when he ie t T ub worked for the Lake Erie Steamship Co. man Frederick Douglass spoke to a full sanctuary at the Michigan Street Baptist Church. In 1905, W.E.B. DuBois, with other black leaders, planned the Niagara Movement and Booker T. -

On and Off the Stage at Atlanta Greek Picnic: Performances of Collective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@Florida International University Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-20-2015 On and Off the tS age at Atlanta Greek Picnic: Performances of Collective Black Middle-Class Identities and the Politics of Belonging Synatra A. Smith Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Synatra A., "On and Off the tS age at Atlanta Greek Picnic: Performances of Collective Black Middle-Class Identities and the Politics of Belonging" (2015). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1906. http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1906 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida ON AND OFF THE STAGE AT ATLANTA GREEK PICNIC: PERFORMANCES OF COLLECTIVE BLACK MIDDLE-CLASS IDENTITIES AND THE POLITICS OF BELONGING A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in GLOBAL AND SOCIOCULTURAL STUDIES by Synatra A. Smith 2015 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts and Sciences This dissertation, written by Synatra A. Smith, and entitled On and Off the Stage at Atlanta Greek Picnic: Performances of Collective Black Middle-Class Identities and the Politics of Belonging, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

UNDERSTANDING RACIAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT THROUGH the EXPERIENCES of BLACK WOMEN in WHITE SORORITIES at PREDOMINANTLY WHITE INSTITUTIONS (Pwis)

RUNNING HEAD: BLACK LIKE ME BLACK LIKE ME: UNDERSTANDING RACIAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT THROUGH THE EXPERIENCES OF BLACK WOMEN IN WHITE SORORITIES AT PREDOMINANTLY WHITE INSTITUTIONS (PWIs) By Joy L. Smith A dissertation submitted to The Graduate School of Education Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education Graduate Program in Social & Philosophical Foundations of Education Approved by ________________________________________ Dr. Beth C. Rubin, Chair ________________________________________ Dr. James Giarelli ________________________________________ Dr. Fred J. Bonner II New Brunswick, New Jersey August, 2018 BLACK LIKE ME Abstract of the Dissertation Du Bois (1902) argues that “being Black” is a consistent identity struggle for people of African descent in the United States because Black identity is often seen as incongruent with the cultural and social values of mainstream America. Tinto (1993) offers that this incongruence is apparent at predominantly White institutions (PWIs) and suggests that participating in racially- centered student organizations allows Black students to “fit in” at PWIs and, in turn, promotes their success in college. Carter (1994) contends that Black identity is not a uniformed experience; socioeconomic status, educational level/attainment and ethnicity/nationality diversify it. This dissertation explored this versatility through the stories of Black women who joined White sororities at PWIs. The goal was to shed light on their experiences, to understand how race is perceived and understood in the lives of those who do not perform race in traditional or stereotypical ways. Secondly, the research delved into the intersected relationship between race, class/socioeconomics and ethnicity/nationality—and the role that it plays in defining Black identity at PWIs. -

Primary & Secondary Sources

Primary & Secondary Sources Brands & Products Agencies & Clients Media & Content Influencers & Licensees Organizations & Associations Government & Education Research & Data Multicultural Media Forecast 2019: Primary & Secondary Sources COPYRIGHT U.S. Multicultural Media Forecast 2019 Exclusive market research & strategic intelligence from PQ Media – Intelligent data for smarter business decisions In partnership with the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers Co-authored at PQM by: Patrick Quinn – President & CEO Leo Kivijarv, PhD – EVP & Research Director Editorial Support at AIMM by: Bill Duggan – Group Executive Vice President, ANA Claudine Waite – Director, Content Marketing, Committees & Conferences, ANA Carlos Santiago – President & Chief Strategist, Santiago Solutions Group Except by express prior written permission from PQ Media LLC or the Association of National Advertisers, no part of this work may be copied or publicly distributed, displayed or disseminated by any means of publication or communication now known or developed hereafter, including in or by any: (i) directory or compilation or other printed publication; (ii) information storage or retrieval system; (iii) electronic device, including any analog or digital visual or audiovisual device or product. PQ Media and the Alliance for Inclusive and Multicultural Marketing at the Association of National Advertisers will protect and defend their copyright and all their other rights in this publication, including under the laws of copyright, misappropriation, trade secrets and unfair competition. All information and data contained in this report is obtained by PQ Media from sources that PQ Media believes to be accurate and reliable. However, errors and omissions in this report may result from human error and malfunctions in electronic conversion and transmission of textual and numeric data. -

Who Taught You to Hate Yourself?: the Racially Coded Language of Professionalism and Its Detriment to the Black Community

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2017 Who Taught You to Hate Yourself?: The Racially Coded Language of Professionalism and its Detriment to the Black Community Alexys Jones Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Alexys, "Who Taught You to Hate Yourself?: The Racially Coded Language of Professionalism and its Detriment to the Black Community" (2017). Online Theses and Dissertations. 535. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/535 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master of Science degree at Eastern Kentucky University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of the source is made. Permission for extensive quotation from or reproduction of this thesis may be granted by my major professor, or in his absence, by the Head of Interlibrary Services when, in the opinion of either, the proposed use of the material is for scholarly purposes. Any copying or use of the material in this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Black History in Buffalo

Black History in Buffalo: Selected Sources in the Grosvenor Room Michigan Street Baptist Church 511 Michigan Avenue Built circa 1843 Key Grosvenor Room * = Oversized book Buffalo and Erie County Public Library Folio = A really oversized book 1 Lafayette Square GRO = In Grosvenor Room Buffalo, New York 14203-1887 NON-FICT = Shelved in the General Non-Fiction Collection (716) 858-8900 STACKS = Shelved in Closed Stacks, ask staff to retrieve www.buffalolib.org MEDIA = Shelved in Media Room November 2020 Ref. = Reference book, cannot be borrowed 1 Table of Contents Databases ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Directories ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Local History File .................................................................................................................................. 4 Newspapers & Periodicals .................................................................................................................... 4 Organizations ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Prominent Black Buffalonians File ........................................................................................................ 5 Scrapbooks .......................................................................................................................................... -

2015-2017 Butterfly Tribune

Gamma Phi Delta Sorority, Inc. Northern Region – 2015-2017 Elizabeth A. Garner BUTTERFLY TRIBUNE Violet T. Lewis Founder Co-Founder Welcome Nu Phi Chapter, Cincinnati ,Ohio to Gamma Phi Delta Sorority, Inc. and the Northern Region-, “The Power of Vision: Empowering Women & Inspiring Leaders” Gamma Phi Delta Sorority, Inc. Northern Region – 2015-2017 Greetings Northern Region Sorors! I would like to give a special 'Thank You' to the Regional Board, Chapter Basilei, Northern Region Sorors, and National Officers for your support and encouragement over the past two years. Consider our Theme: The Power of Vision: Empowering Women and Inspiring Leaders. The Power of Vision - 'The act or power of anticipating that which will or may come to be.' How many times have you had an idea or concept and was blessed to see it come to fruition? Empowering Women - 'To give power or authority to; authorize, especially by legal or official means.' How many women have you supported and encouraged to increase their power and authority over their own lives? Inspiring Leaders - 'To influence, fill, or affect with a specified feeling or thought.' How are you assisting others in their efforts to advance in their careers, organizations and/or associations? Our Theme, considered long by some, if studied, and put into action, will change the course of someone's life. What will you do today, How will you encourage someone today, Who will you support today? It all begins with You! Let's increase our ideas, continue our empowerment of women and be supportive of our leaders for we are: The Mighty Northern Region of Gamma Phi Delta Sorority, Inc. -

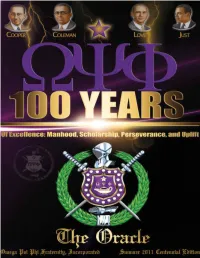

1 the Oracle

The Oracle - Summer 2011 Centennial Edition 1 Editor to The Oracle Brother Michael A. Boykin, MAJ 3951 Snapfinger Parkway Decatur, GA 30035 Email: [email protected] District Directors of Public Relations The Oracle 1st Brother Al-Rahim Williams 2nd Brother Zanes Cypress, Jr. 3rd Brother Terrence Gilliam 4th Brother Bryan K. Dirke Volume 81 * No. 24 5th Brother L. Rodney Bennett 6th Brother Byron Putman * Summer 2011 7th Brother Darron Toston 8th Brother Osuman Issaka The official publication of 9th Brother Van Newborn 10th Brother Robert Browne Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. 12th Brother Robert L. Woodson 13th Brother Kevin Williams The Oracle is published quarterly (spring, summer, fall and winter) Graphic Design Team by Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Brother Craig Ballard Brother David Shelton at its publications office: Brother Sean Long Brother Michael Taylor 3951 Snapfinger Parkway, Decatur, GA 30035. International Photographer Emeritus Send address changes to: Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Brother John H. Williams Attn: Grand KRS 3951 Snapfinger Parkway Decatur, GA 30035 International Photographers Brother Reginald Braddock * The Oracle deadlines are: Brother Galvin Crisp Spring issue - February 15 Brother James Witherspoon Summer issue - May 15 Fall issue - August 15 Winter issue - November 15 39th Grand Basileus *Deadlines are subject to change. Brother Dr. Andrew A. Ray Cover by Brother Sean T. Long # 5 Chi Lambda Lambda 2009 Chicago, IL 2 The Oracle - Summer 2011 Centennial Edition The Oracle Contents 5 Supreme Council Roster 12 6 Grand Basilei 8 Message from the Grand Basileus 9 Message from the First Vice Grand Basileus 10 Message from the Features Second Vice Grand Basileus 12 Farewell Tribute 12 Farewell Tribute to 28th Grand 28th Grand Basileus James S. -

Volume 19, No.11 January 05, 2011

Volume 19, No.11“And Ye Shall Know The Truth...” January 05, 2011 In This Issue The Truth Editorial Page 2 Perryman Page 3 Ashford Page 4 Kwanzaa Page 5 Health Section Eating Healthy Page 6 2010 Resolutions Page 7 Another Health Care Bill Page 7 NAMI Page 8 Angela Steward Page 9 Ask Ryan Page 10 Book Review Page 11 Minister Page 13 BlackMarketPlace Page 14 Classifieds Page 15 Page 2 The Sojourner’s Truth January 05, 2011 This Strikes Us … Community Calendar A Sojourner’s Truth Editorial January 8 Ah, celebrity! Ain’t it grand? West Toledo Bereavement Ministry Monthly Meeting: 1430 W. Bancroft; 10 Michael Vick is back atop the world of professional sports and his return has created am: 567-249-7470 the kind of consternation that defies logic. Serenity C.O.G.I.C. Building Fundraiser: All you-can-eat Fish Fry; Serenity President Obama praises Vick’s current employers for providing the ex-offender with Soul Food Restaurant on Woodville; 2 to 6 pm: 419-671-6265 a second chance. Conservative pundit Tucker Carlson calls such presidential comments “beyond the pale” and opines that Vick should have been executed for his many crimes January 11 of killing dogs. For his own part, Vick has expressed remorse over and over again for his past actions, Community Resource Fair: Hosted by Washington Local Schools; Whitmer he has served a prison term, he has come to terms with bankruptcy, he has re-committed Cafeteria; 4 to 7 pm; Allowing families to access community agencies in a one- himself to his craft in a manner conspicuously missing from his first turn in the league, he stop-shop setting; Free to all Toledoans; Over 40 local agencies will be present: has lectured students on the pitfalls of following in his path and, by the way, he has become, 419-473-8237 if not the NFL’s most valuable player, part of that conversation. -

The History, Perceptions and Principles of Black Greek Lettered Organizations at Ole Miss

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2016 The Fly In The Buttermilk: The History, Perceptions And Principles Of Black Greek Lettered Organizations At Ole Miss Ashley F. G. Norwood University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Norwood, Ashley F. G., "The Fly In The Buttermilk: The History, Perceptions And Principles Of Black Greek Lettered Organizations At Ole Miss" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 657. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/657 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FLY IN THE BUTTERMILK: THE HISTORY, PERCEPTIONS AND PRINCIPLES OF BLACK GREEK LETTERED ORGANIZATIONS AT OLE MISS A Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Meek School of Journalism and New Media The University of Mississippi by Ashley F. G. Norwood May 2016 Copyright Ashley F. G. Norwood 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT At the University of Mississippi, engaging across racial and cultural lines is still something many find difficult, or they simply don’t want to do it. Over the years, the university has chartered a variety of culture specific organizations, counsels and groups. In 1973, the first black Greek-lettered organization chartered at the university. The presence of black fraternalism is culturally different from the white Greeks that have been established on campus as early as the 1850s.