The Craft of Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCANTRO Theatre

Tony Locantro Programmes – Theatre MSS 792 T3743.L Theatre Date Performance Details Albery Theatre 1997 Pygmalion Bernard Shaw Dir: Ray Cooney Roy Marsden, Carli Norris, Michael Elphick 2004 Endgame Samuel Beckett Dir: Matthew Warchus Michael Gambon, Lee Evans, Liz Smith, Geoffrey Hutchins Suddenly Last Summer Tennessee Williams Dir: Michael Grandage Diana Rigg, Victoria Hamilton 2006 Blackbird Dir: Peter Stein Roger Allam, Jodhi May Theatre Date Performance Details Aldwych Theatre 1966 Belcher’s Luck by David Mercer Dir: David Jones Helen Fraser, Sebastian Shaw, John Hurt Royal Shakespeare Company 1964 (The) Birds by Aristophanes Dir: Karolos Koun Greek Art Theatre Company 1983 Charley’s Aunt by Brandon Thomas Dir: Peter James & Peter Wilson Griff Rhys Jones, Maxine Audley, Bernard Bresslaw 1961(?) Comedy of Errors by W. Shakespeare Christmas Season R.S.C. Diana Rigg 1966 Compagna dei Giovani World Theatre Season Rules of the Game & Six Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello Dir: Giorgio de Lullo (in Italian) 1964-67 Royal Shakespeare Company World Theatre Season Brochures 1964-69 Royal Shakespeare Company Repertoire Brochures 1964 Royal Shakespeare Theatre Club Repertoire Brochure Theatre Date Performance Details Ambassadors 1960 (The) Mousetrap Agatha Christie Dir: Peter Saunders Anthony Oliver, David Aylmer 1983 Theatre of Comedy Company Repertoire Brochure (including the Shaftesbury Theatre) Theatre Date Performance Details Alexandra – Undated (The) Platinum Cat Birmingham Roger Longrigg Dir: Beverley Cross Kenneth -

Vivien Leigh, Actress and Icon: Introduction Kate Dorney and Maggie B

1 Vivien Leigh, actress and icon: introduction Kate Dorney and Maggie B. Gale This volume of essays has been generated as a response to the Victoria and Albert Museum ’ s 2013 acquisition of twentieth-century actress Vivien Leigh ’ s personal archive made up of, amongst other things: letters, scripts, photographs, personal documents, bills, speeches, appointment diaries, lists of luggage contents for tours and even lists of domestic items for repair. Among the tasks this introductory chapter undertakes is to outline the ways in which the archive has been con- structed – which elements were put together by Leigh ’ s mother and daughter, how the archive was and has since been arranged – and what the constructed nature of this evidence might tell us about the curation of Leigh ’ s life and legacy. 1 Many of the essays in this volume have made use of materials from the archive, as well as drawing on other related collections such as the Laurence Olivier archive at the British Library and the Jack Merivale papers at the British Film Institute. These mate- rials have been used in combination with contemporary approaches to theatre historiography, feminist biography and screen and celebrity studies with the specifi c aim of providing new readings of Leigh as an actress and public fi gure. Vivien Leigh: Actress and Icon explores the frameworks within which Leigh ’ s work has been analysed to date. We are interested in how she, and others, shaped and projected her public persona, and construc- tions of her personal and domestic life, as well as looking at the ways in which she approached the craft of acting for stage and screen. -

12 the Odd Woman Margaret Rutherford

12 The odd woman Margaret Rutherford John Stokes Although Margaret Rutherford’s (1892–1972) presence became famil- iar to an enormous public, she remained in her performances the odd woman out: at times ‘difficult’, yet irrepressible; peculiar in dress, man- nerism, speech, yet invariably to the fore. With their predilection for physical detail, at best careless, at worst cruel, all too commonplace at the time, critics liked to make fun of her features: her trembling chins, pursed lips, popping eyes, her mobile eyebrows. She was certainly physi- cally memorable. Her whole body seemed to invite comment, especially when on the move: clasped hands, large strides interspersed with sudden darts, a bustling and, at the same time, purposive gait. Over the years her costumes and props became standardised: umbrella, beads, specta- cles (alternating with lorgnette, monocle, even binoculars), a capacious shawl (or shapeless cape) and, always to top it off, floral hats that seemed to lead a horticultural life of their own. Throughout her career reviewers turned to animal epithets to describe her, but they were strangely mixed: porpoise, dragon, moth. It’s as if the journalists were competing not only among themselves but with the actress herself in their attempts to capture her presence in a single stroke. Rutherford’s origins were unusual. A significant number of the actresses who achieved prominence in the early twentieth century came from a theatrical background – a vocational advantage that had often led to early starts as a child performer. The father of Fay Compton (1894– 1978), for instance, was the actor Edward Compton, and she was acting professionally by 1911; Nina Boucicault (1867–1950) was a member of a long-standing theatrical dynasty; Joyce Carey (1898–1952) was the daugh- ter of the actors Gerald Lawrence and Lilian Braithwaite. -

The Ageing Woman in British Film Comedy of the Mid-Twentieth Century

Battleaxes, Spinsters and Chars: the Ageing Woman in British Film Comedy of the Mid-Twentieth Century Submitted by Claire Mortimer Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art, Media and American Studies University of East Anglia February 2017 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Word count: 94 090 i Abstract ‘Battleaxes, Spinsters and Chars: the Ageing Woman in British Film Comedy of the Mid- Twentieth Century’ explores the prominence of the mature woman in British film comedies of the mid-twentieth century, spanning the period from the Second War World to the mid- 1960s. This thesis is structured around case studies featuring a range of film comedies from across this era, selected for the performances of character actresses who were familiar faces to British cinema audiences. Organised chronologically, each chapter centres around films and actresses evoking specific typologies and themes relevant to female ageing: the ‘immobile’ woman in wartime, the spinster in the post-war era, retirement and old age in the 1950s, and the cockney matriarch in the early 1960s. The selection of case studies encompasses the overlooked and critically derided alongside the more celebrated and better known in order to represent the range of British film comedy of the time. The final chapter spans the time-frame of the whole thesis, exploring the later life stardom of Margaret Rutherford. -

Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Neil Heayes

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Neil Heayes – interview transcript Interviewer: Natalie Dunton 16 January 2008 Theatre-goer. Peggy Ashcroft; Robert Atkins; Brixton Theatre; Jack Buchanan; Cyrano de Bergerac; The First Gentleman; John Gielgud; Hamlet; Haymarket Theatre; Robert Helpmann; Mona Inglesby and the International Ballet Company; King Lear; King's Theatre, Hammersmith; Esmond Knight; Vivien Leigh; Love for Love; Lupino family; Oedipus Rex and The Critic; Old Vic; Laurence Olivier; Open Air Theatre, Regent's Park; Paganini; programmes; Ralph Richardson; the Savoy Operas; Firth Shepherd; Alistair Simm; Streatham Hill Theatre; the Travelling Repertory Theatre; ticket prices; Rex Whistler; Donald Wolfit. ND: If we go… you were saying about when you or rather you got interested in the theatre when you were 14 years old? NH: Yes, 14 years old. As I say, I was very young in those days, I was working. But unfortunately I went along through Farrington Street, these famous book shops they had - book stalls they were, they had them all over the place - and they had this splendid book of programmes that someone had collected from the 1920s. And I thought that was marvellous and I would love to have it. Unfortunately I didn’t have enough money with me so I went back the next day with my money and of course the book had gone! So instead I decided to take my own collection of programmes, so I started from when I was about 14, which was just about 1945 just towards the end of the war, ‘44/‘45. One of the earliest things I did see in the West End was the Shakespearean actor Donald Wolfit. -

Handlist of the J.C. Trewin Collection

1 J C Trewin MS 4739 Historical letters 1/1 22 September, undated. Constance Benson (wife of Shakespearian actor Frank) to Mr Neilson. 1/2 3 April 1932. Constance Benson to Sir Archibald Flower, of the Stratford brewing family who were supportive of the early Stratford theatres. Regretfully declining Sir Archibald’s invitation to attend the opening ceremony of the new theatre in Stratford- upon-Avon as she could not meet her husband, Frank, in public due to a past disagreement. 1/3 2 February 1940. Constance Benson to Sir Archibald Flower. Discusses where to scatter the ashes of Frank Benson and is glad that they were reconciled before he died. 1/4 9 May 1940. Constance Benson to Sir Archibald Flower. Sending him a pin, the implication is that it belonged to her husband, Frank, for she nearly gave it to her ex pupil John Gielgud. Constance Benson’s daughter is referred to in these letters as Dick and Bryn. 2 31 January 1940. Sir Archibald Flower to Constance Benson (copy). Concerning the disposal of Frank Benson’s ashes. 3 20 April 1932. Peggy to ‘Dearest Scopie’, written from 1 Scarsdale Villas (the same address headed Constance Benson’s letters), copy. Concerning the financial support given to Frank Benson and his lack of acknowledgement, letter could be from Constance Benson. 4 21 March 1919. Frank Benson to Tommy Merton. 5 8 January 1940. C F Leyel to Mr Howson declining invitation to Sir Frank Benson’s memorial service. 6/1 14 August 1896. Sir John Hare to Sydney Grundy. -

The Performing Arts on Film and Television Catalogue

THE PERFORMING ARTS ON FILM & TELEVISION CATALOGUE Film and video materials held by the archives and collections of BFI, Arts Council England, LUX, Central St Martins British Artists Film & Video Study Collection relating to theatre, dance, music, performance art, politics and poetry Balletomines, 1954 2011 Acknowledgements This catalogue was commissioned by MI:LL (Moving Image: Legacy and Learning), an Arts Council England initiative to support projects and develop strategies that promote engagement with the arts through the moving image. Researched, written, edited, designed and published by Helena Blaker James Bell Michael Brooke Elaine Burrows Bryony Dixon Christophe Dupin Jane Giles Amy Howerska Edward Lawrenson Deborah Salter Dan Smith Louise Watson With thanks to Karen Alexander, Nigel Algar, Nigel Arthur, Steve Bryant, Mike Caldwell, Ros Cranston, David Curtis, Will Fowler, Philippa Johns, Nathalie Morris, Patrick Russell, David Sin, Mike Sperlinger, Gary Thomas, Rebecca Vick, Ian White, Andrew Youdell and Juliane Zenke. All stills courtesy of BFI Stills, Posters & Designs A BFI Publication 2011 available to download from www.bfi.org.uk BFI 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN UK Telephone +44 (020) 7255 1444 www.bfi.org.uk 2 Contents Please click on a word/link to be taken automatically to that part of the Catalogue Acknowledgements................................................................................................................. 2 Contents .................................................................................................................................. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfil

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there a re missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A ccessing the UMIWorld's Information sin ce 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820327 The Company of Four at the Lyric, Hammersmith: A paradigm for the emergent National Theatre concept Murphy, Hugh Mack, Jr., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Murphy, Hugh Mack, Jr. All rights reserved. UMI SOON. ZeebRd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 THE COMPANY OF FOUR AT THE LYRIC, HAMMERSMITH: A PARADIGM FOR THE EMERGENT NATIONAL THEATRE CONCEPT DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hugh Mack Murphy, Jr., B.A., M.A. -

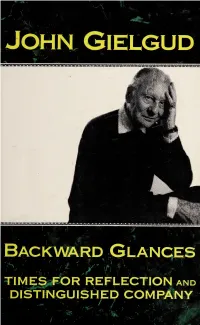

Backward Glances Nodrm

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation https://archive.org/details/backwardglancesOOgiel John Gielgud Backward Glances Part One TIMES FOR REFLECTION Part Two DISTINGUISHED COMPANY LIMELIGHT EDITIONS NEW YORK First Limelight Edition July 1990 Copyright © John Gielgud 1972, 1989 Published by arrangement with Hodder and Stoughton Limited, London. Parts of this book were first published in the United States as Distinguished Company in 1972, by Doubleday & Co. First published in its present edition by Hodder and Stoughton Limited in 1989. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gielgud, John, Sir, 1904- Backward glances / John Gielgud. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-87910-140-7 1. Gielgud, John, Sir, 1904- . 2. Gielgud, John, Sir, 1904— —Friends and associates. 3. Actors—Great Britain-Biography. I. Title. PN2598.G45A3 1990 792'.028'o92-dc20 [B] 90-36754 CIP To Gwen and Peggy, my two dear and lovely Juliets CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Foreword ix Times for Reflection 1. Edith Evans: A Great Actress 3 2. Sybil Thorndike: A Great Woman 8 3. Ralph Richardson: A Great Gentleman, A Rare Spirit 13 4. Elizabeth Bergner 17 5. Vivien Leigh 23 6. Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies 27 7. Golden Days: The Guitry’s 32 8. Eminent Victorians: Sir Squire Bancroft, Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson, Dame Madge Kendal 37 9.