Ministers Appointed to Karori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Water & Sanitary Services

Assessment of Water and Sanitary Services 2005 For the purpose of the water supply assessment Wellington City has been broken down into Brooklyn, Churton, Eastern Wellington, Johnsonville, Karori, Kelburn, Onslow, Southern Wellington, Wadestown, Tawa and Wellington Central. These are based on the MoH distribution zones in which these communities receive similar quality water from its taps. There are three main wastewater catchments in the city terminating at the treatment plants at Moa Point, Karori (Western) and in Porirua City. These will be treated as three communities for the wastewater part of this assessment. There are 42 stormwater catchments, defined by topography, in the Wellington area. These will form the communities for this part of this assessment. Table 1 shows the water, wastewater and stormwater communities in relation to each other. In the case of sanitary services, the community has been defined as the entire area of Wellington City. There are no major facilities (i.e. the hospital, educational institutions or the prisons) that are not owned by Council which have their own water supplies or disposal systems. 2.2 Non-reticulated communities The non-reticulated communities have been separated into the rural communities of Makara, Ohariu Valley, South Karori Horokiwi and the smaller Glenside settlement. Within the Makara community another community can be defined which is the Meridian Village. Within the first four communities all properties have individual methods of collecting potable water and disposing of waste and stormwater. The Meridian village has a combined water and wastewater system. There are 6 properties in Glenside which rely on unreticulated water supply, though there is uncertainty to which houses are served by the Councils wastewater system. -

Explore Wellington

EXPLORE Old Coach Rd 1 Makara Peak Mountain Bike Park This dual use track runs North SKYLINE and South along the ridge MAORI HISTORY AND KEY Wellington City Council set aside 200 TRACK between Old Coach Road in SIGNIFICANCE OUTER GREEN START/FINISH hectares of retired farmland South- EXPLORE Johnsonville and Makara Saddle BELT Carmichael St West of the city for a mountain bike in Karori. park in 1998. Volunteers immediately While European settlers named parts of the skyline, SKYLINE TRACK most of the central ridge was known to local Maori began development of the Makara Allow up to five hours to traverse 12kms of Wellington’s ridge tops 2 as Te Wharangi (broad open space). This ridge was Peak Mountain Bike Park by planting WELLINGTON following the Outer Green Belt onto Mt Kaukau, the Crow’s Nest, NORTHERN Truscott Ave not inhabited by Maori, but they traversed frequently trees and cutting new tracks. In the Discover Wellington’s Town Belt, reserves and walkways Kilmister Tops and Johnston Hill. Take time to indulge in the stunning WALKWAY Reserve and by foot when moving between Te Whanganui-a- Johnsonville Park first year, six tracks were built and rural, city and coastal views along the way. On a clear day, views of Tara and Owhariu. EXISTING TRACK 14,000 native seedlings planted. the Kaikoura ranges, the Marlborough Sounds, Wellington city and John Sims Dr Nalanda Cres A significant effort was also put into MT KAUKAU 3 dleiferooM dR harbour, and the Tararua and Orongorongo ranges will take your The Old Maori Trail runs from Makara Beach all the 1 9 POINTS OF controlling possums and goats, breath away. -

Tuesday 20Th February 2018

v. 8 February 2018 Tuesday 20th February 2018 Pre-Conference Workshops Times and Rooms Rutherford House, Pipitea Campus, Victoria University of Wellington 1.30pm - 5.00pm Ecosystem-based adaption to climate change across the Pacific Facilitators: Paul Blaschke, School of Environment, Geography and Earth Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington; David Loubser, Pacific Ecosystem-based Room: MZ05/06 Adaptation to Climate Change Programme - Vanuatu Country Manager, SPREP 2.00pm – 4.30pm Engaging Pacific Islands on SRM geoengineering research Facilitators: Andy Parker, Project Director – SRMGI; Penehuro Lefale, Director - LeA International Room: Z06 Speakers: Douglas MacMartin, Cornell University; Dr Morgan Wairriu, Deputy Director of USP PACE 2.00pm – 4.30pm Climate change media and communication workshop - Supported by New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO Room: RH101 Facilitator: Dacia Herbulock, Senior Media Advisor, Science Media Centre, New Zealand International cooperation after the Paris Agreement. What makes sense for the Pacific? 2.00pm-4.00pm Facilitator: Adrian Macey, Institute for Governance and Policy Studies; Climate Change Research Institute, Victoria University of Room: tbc Wellington Pre-Conference Public Lecture Rutherford House, Pipitea Campus, Victoria University of Wellington, Lecture Theatre 2 5.30pm Law as an Activism Strategy, Julian Aguon, Associate Professor Kapua Sproat, Ani Mikaere- Supported by The New Zealand National Law Foundation Wednesday 21st February 2018 7.00am – 5.00pm Registration open in Oceania -

Karori Water Supply Dams and Reservoirs Register Report

IPENZ Engineering Heritage Register Report Karori Water Supply Dams and Reservoirs Written by: Karen Astwood and Georgina Fell Date: 12 September 2012 Aerial view of Karori Reservoir, Wellington, 10 February 1985. Dominion Post (Newspaper): Photographic negatives and prints of the Evening Post and Dominion newspapers, Alexander Turnbull Library (ATL), Wellington, New Zealand, ID: EP/1984/0621. The Lower Karori Dam and Reservoir is in the foreground and the Upper Karori Dam and Reservoir is towards the top of the image. 1 Contents A. General information ........................................................................................................... 3 B. Description ......................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Historical narrative .................................................................................................................... 6 Social narrative ...................................................................................................................... 10 Physical narrative ................................................................................................................... 18 C. Assessment of significance ............................................................................................. 24 D. Supporting information ..................................................................................................... -

Our Wellington 1 April-15 June 2021

Your free guide to Tō Tātou Pōneke life in the capital Our Wellington 1 April — 15 June 2021 Rārangi upoku Contents Acting now to deliver a city fit for the future 3 14 29 Kia ora koutou An important focus for the 2021 LTP is on Did you know you can… Planning for our future Autumn gardening tips This year will be shaped by the 2021 Long-Term infrastructure – renewing old pipes, ongoing Our contact details and Spotlight on the From the Botanic Garden Plan (LTP) and as such, is set to be a year of investment in resilient water and wastewater supply, and on a long-term solution to treat the helpful hints Long-Term Plan important, long-lasting, city-shaping decisions. 31 Every three years we review our LTP sludge by-product from sewage treatment. 5 16 Ngā huihuinga o te with a community engagement programme All this is expensive, and we’ve been Wā tākaro | Playtime Tō tātou hāpori | Our Kaunihera, ngā komiti me that sets the city-wide direction for the next working hard to balance what needs to be done with affordability. Low-cost whānau-friendly community ngā poari ā-hapori 10 years. It outlines what we will be investing in, how much it may cost, and how this will Your input into the LTP and planning for activities The life of a park ranger Council, committee and be funded. It provides guidance on how we Te Ngākau Civic Square, Let’s Get Wellington community board meetings 6 18 will make Wellington an even better place Moving and Climate Change will be critical in helping balance priorities and developing Pitopito kōrero | News Ngā mahi whakangahau 32 to live, work, play and visit as we go into the future. -

Navigation Report on New Zealand King Salmon's

NAVIGATION REPORT ON NEW ZEALAND KING SALMON’S PROPOSAL FOR NEW SALMON FARMS IN THE MARLBOROUGH SOUNDS 29 SEPTEMBER 2011 BY DAVID WALKER CONTENTS PAGE NO. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION 3 Current Position 3 History of involvement in Marlborough Sounds 3 Aquaculture 3 Maritime education and training 4 Qualifications 4 Experience on large vessels 5 Key references 5 SCOPE OF REPORT 7 THE MARLBOROUGH SOUNDS FROM A NAVIGATION PERSPECTIVE: 8 Navigation 8 Electronic Navigation 9 Weather 11 Visibility 11 Fog 11 Tides 12 Marine farms 13 NAVIGATION IN QUEEN CHARLOTTE SOUND 13 NAVIGATION IN TORY CHANNEL 14 PELORUS SOUND 16 PORT GORE 17 NAVIGATION AND SALMON FARMS 19 Commercial vessels over 500 gross tonnage within the designated Pilotage Area 19 Commercial small boats 21 Recreational small boats 22 Collisions between vessels and marine farms 23 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN VESSELS AND MARINE FARMS 25 Beneficial effects of the farms on navigational safety 26 NAVIGATIONAL ISSUES RELATING TO THE PROPOSED SITES 26 Waitata Reach 26 Papatua 28 Ngamahau 30 Ruaomoko and Kaitapeha 33 CONDITIONS TO BE IMPOSED 36 Notification to Mariners/Education 36 Buoyage 37 Restricted visibility 37 Lighting 38 Engineering 39 AIS 40 Emergency procedures 41 Executive summary 1. This report was commissioned by The New Zealand NZ King Salmon Company Ltd (NZ King Salmon) and assesses the effects of NZ King Salmon’s proposal for nine new marine farm sites on navigation in the Marlborough Sounds. In summary, my view as an experienced navigator, both within the Marlborough Sounds and elsewhere, is that provided the farms operate under an appropriate set of conditions the farms will have the following effect on navigation: a. -

Penguin Self-Guided Walk

WCC024 Penguin cover.pART 11/23/05 10:26 AM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Composite PENGUIN SELF GUIDED WALK KARORI CEMETERY HERITAGE TRAIL Thiswalk takes about togo minutes to two hours. Markers direct you round the walk, all the paths are sign posted and the graves are marked with the Penguinwreck marker. The walk startsat the Hale memorial and finishes at the second Penguin memorial in the Roman Catholic section of the cemetery. The WellingtonOty Coundl gratefullyacknowledges the assistance of BruteE Colllns,author of The WTedrO/thePfnguln,Steell! Roberts, Wellington and of RogerSteeleofsteele Roberts. Historical research:Delrdre TWogan, Karorl HistoricalSociety Author. DeirdreTWogan Wellington CityCouncil is a memberof the HeritageTrails Foundation Brochuresfor other Coundl walksare availableat theVIsitor InformationonJce lm Wakefleld Street. You can also visit the WellingtonCity Coundl on-line at www.wellington.gavt.nz (overimage: Penguinleaving Wellington (Zak PhDlDgraph, Hocken LibrillY) Wellington City Council Introduction The wreck of the Penguin on 12 February 1909 with a death toll of 72 was the greatest New Zealand maritime disaster of the 20th century. The ship went down in Cook Strait, only a few kilometres from where the Wahine was wrecked in April 1968, with the loss of 51 lives. Built of iron in 1864, on its Glasgow-Liverpool run the Penguin was reputed to be one of the fastest and most reliable steamers working in the Irish Sea. At the time of the wreck she had served the Union Steam Ship Company for 25 years, most recently on the Lyttelton and Cook Strait run. The Risso’s dolphin known to thousands as Pelorus Jack cavorted round the Penguin’s bows in the early years of the century, but after a collision in 1904 kept its distance — until January 1909 when it suddenly reappeared. -

12 Schedules Schedules 12 Schedules

12 Schedules 12 Schedules 12 Schedules 12 Schedules contents Schedule Page number Schedule A: Outstanding water bodies A1-A3 279 Schedule B: Ngā Taonga Nui a Kiwa B 281 Schedule C: Sites with significant mana whenua values C1-C5 294 Schedule D: Statutory Acknowledgements D1-D2 304 Schedule E: Sites with significant historic heritage values E1-E5 333 Schedule F: Ecosystems and habitats with significant indigenous biodiversity values F1-F5 352 Schedule G: Principles to be applied when proposing and considering mitigation and G 407 offsetting in relation to biodiversity Schedule H: Contact recreation and Māori customary use H1-H2 410 Schedule I: Important trout fishery rivers and spawning waters I 413 Schedule J: Significant geological features in the coastal marine area J 415 Schedule K: Significant surf breaks K 418 Schedule L: Air quality L1-L2 420 Schedule M: Community drinking water supply abstraction points M1-M2 428 Schedule N: Stormwater management strategy N 431 Schedule O: Plantation forestry harvest plan O 433 Schedule P: Classifying and managing groundwater and surface water connectivity P 434 Schedule Q: Reasonable and efficient use criteria Q 436 Schedule R: Guideline for stepdown allocations R 438 Schedule S: Guideline for measuring and reporting of water takes S 439 Schedule T: Pumping test T 440 Schedule U:Trigger levels for river and stream mouth cutting U 442 PROPOSED NATURAL RESOURCES PLAN FOR THE WELLINGTON REGION (31.07.2015) 278 Schedule A: Outstanding water bodies Schedule A1: Rivers with outstanding indigenous ecosystem -

Celia Wade-Brown

Section 112A, Local Electoral Act 2001 I, Celia Margaret Wade-Brown was a candidate for the following elections held on 12 October 2013: Mayor of Wellington City Council Part A Return of electoral donations I make the following return of all electoral donations received by me that exceed $1,500: Amount paid to Name of donor (state Campaign to which Electoral Officer "anonymous" if an Address of donor (leave donation and date payment anonymous donation) blank if anonymous) Amount Date received designated made (if an anonymous (if an anonymous donation) donation) Monthly AP $100 from 20-Dec- 2011to20-Feb-2013. Monthly Kent Duston 115A Pirie Street, Mt Victoria $2,550.00 AP $150 from 20-Mar-2013. Monthly AP $30 from 21-Sep- Mike Ennis 36 Pembroke Street, Northland $750.00 2011 Roy Elgar Helleruo, Denmark $250.00 1-Jul-13 David Zwartz 54 Central Terrace, Kelburn $200.00 4-Aug-13 Jan Rivers 86 Parkvale Rd, Karori $100.00 22-Aug-13 Stephen Dav 167 Buckley Rd Southqate $50.00 23-Aug-13 Don McDonald 181 Daniel St, Newtown $5.00 29-Aug-13 P J Barrett 10 Hanson Street, Newtown $300.00 1-Seo-13 Part B Return of electoral expenses I make the following return of all electoral expenses incurred by me: Name and description of person or body of persons Total expense paid to whom sum paid Reason for expense l(GST incl.) Capital Magazine Advertising $1,319.64 Luxon Advertising Ltd Ad-Shels $14,701.62 Fish head Advertising $1,552.50 Northern courier Advertisinq $3,561.55 Salient Advertising $478.98 Tattler Advertising $247.25 Valley Voice Advertising $100.00 -

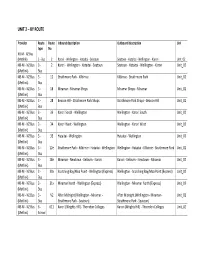

Unit 2 – by Route

UNIT 2 – BY ROUTE Provider Route Route Inbound description Outbound description Unit type No. NB -M - NZ Bus (Metlink) 3 - Bus 2 Karori - Wellington - Hataitai - Seatoun Seatoun - Hataitai - Wellington - Karori Unit_02 NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 2 Karori - Wellington - Hataitai - Seatoun Seatoun - Hataitai - Wellington - Karori Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 12 Strathmore Park - Kilbirnie Kilbirnie - Strathmore Park Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 18 Miramar - Miramar Shops Miramar Shops - Miramar Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 28 Beacon Hill - Strathmore Park Shops Strathmore Park Shops - Beacon Hill Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 33 Karori South - Wellington Wellington - Karori South Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 34 Karori West - Wellington Wellington - Karori West Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 35 Hataitai - Wellington Hataitai - Wellington Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 12e Strathmore Park - Kilbirnie - Hataitai - Wellington Wellington - Hataitai - Kilbirnie - Strathmore Park Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 18e Miramar - Newtown - Kelburn - Karori Karori - Kelburn - Newtown - Miramar Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 30x Scorching Bay/Moa Point - Wellington (Express) Wellington - Scorching Bay/Moa Point (Express) Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - 31x Miramar North - Wellington (Express) Wellington - Miramar North (Express) Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus NB-M - NZ Bus 3 - N2 After Midnight (Wellington - Miramar - After Midnight (Wellington - Miramar - Unit_02 (Metlink) Bus Strathmore Park - Seatoun) Strathmore Park - Seatoun) NB-M - NZ Bus 6 - 611 Karori (Wrights Hill) - Thorndon Colleges Karori (Wrights Hill) - Thorndon Colleges Unit_02 (Metlink) School Provider Route Route Inbound description Outbound description Unit type No. -

60E Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

60E bus time schedule & line map 60E Porirua - Tawa - Johnsonville - Wellington View In Website Mode The 60E bus line (Porirua - Tawa - Johnsonville - Wellington) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Courtenay Place - Stop A →Porirua Station - Stop B: 4:08 PM - 5:55 PM (2) Courtenay Place - Stop A →Whitireia Polytechnic - Titahi Bay Road: 7:33 AM - 7:52 AM (3) Porirua Station - Stop B →Courtenay Place - Stop C: 6:25 AM - 7:45 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 60E bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 60E bus arriving. Direction: Courtenay Place - Stop A →Porirua 60E bus Time Schedule Station - Stop B Courtenay Place - Stop A →Porirua Station - Stop B 49 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Courtenay Place - Stop A 25 Courtenay Place, New Zealand Tuesday Not Operational Courtenay Place at St James Theatre Wednesday 4:08 PM - 5:55 PM 77 Courtenay Place, New Zealand Thursday 4:08 PM - 5:55 PM Manners Street at Cuba Street - Stop A Friday 4:08 PM - 5:55 PM 106 Manners Street, New Zealand Saturday Not Operational Manners Street at Willis Street 2 Manners Street, New Zealand Willis Street at Grand Arcade 12 Willis Street, New Zealand 60E bus Info Direction: Courtenay Place - Stop A →Porirua Station Lambton Quay at Cable Car Lane - Stop B 256 Lambton Quay, New Zealand Stops: 49 Trip Duration: 56 min Lambton Central - Stop A Line Summary: Courtenay Place - Stop A, Courtenay 204 Lambton Quay, New Zealand Place at St James Theatre, Manners Street -

Let's Get Wellington Moving

Let’s Get Wellington Moving: Time To Re-focus © Copyright Karori Residents’ Association Author Bill Guest 2 March 2021 Introduction In 2001 the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) began considering how to connect the Wellington foothills motorway to the planned second tunnel through Mount Victoria. The new tunnel was to be located slightly north of the present tunnel, and parallel to it. 14 years later, after years of bickering and court cases, the proposed bridged highway on the north side of the Basin Reserve was defeated by the decision of the High Court not to overturn the decision of Commissioners to decline the resource consent required to proceed. While the Mayor of Wellington at the time, and several Councillors expressed pleasure at the decision, the only positive solutions suggested seemed to be “mass transit/light rail” and “cycleways” without a clear strategy or justification for either. In 2016 NZTA reached an agreement with Wellington City Council (WCC) and Greater Wellington City Council (GWRC) to form a joint planning group to devise and implement solutions to the growing congestion problems in Wellington City. The group became known as Let’s Get Wellington Moving (LGWM). Karori Residents Association is concerned about LGWM and believes that it is urgent that WCC asserts its position as the planning authority for the city and seeks a significant re-focus of the work of LGWM. Background When the Wellington foot-hills motorway was built in the late 1960s, the intention was to swing eastwards after passing through the new Terrace tunnel, and to cross over Aro Flat to meet the both the old (1931) and a new Mt Victoria tunnel.