Neighborhoods at the Edge of the Walking City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form

FHR-a-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Krank Building and/or common Iris Park Place 2. Location street & number 1855 W. University N/A not for publication city, town St. Paul N/A vicinity of congressional district 4th 123 state Minnesota code 232 county Ramsey code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied X commercial park structure both X work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible __ entertainment religious object N/A in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner off Property name Palen-Kimball Company street & number 2505 W. University Avenue city,town St. Paul N/A vicinity of state Minnesota 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Ramsey County Courthouse street & number 15 W. Kellogg Boulevard city, town St. Paul state Minnesota 55102 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic Sites Survey of title St. Paul and Ramsey County has this property been determined elegible? yes y no X date 12/80-11/82 federal state county X local Ramsey County Historical Society depository for survey records 75 W. Fifth Street, Room 323 city, town St. Paul state Minnesota 55102 7. Description Condition Check one Check one * excellent , deteriorated unaltered X original site X -.good « *<* **" • ruins X altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The A. -

Application for the FOREMAN & CLARK BUILDING

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC -200 8-4978 -HCM HEARING DATE: January 15, 2009 Location: 701 South Hill St. TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 9 PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Central City 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: Central Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Downtown Los Angeles 90012 Legal Description: FR4 of Mueller Subdivision of the North ½ of Block 26 Ord’s Survey PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the FOREMAN & CLARK BUILDING REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER/ Kyung Ku Cho c/o Young Ju Kwon APPLICANT: 3200 Wilshire Blvd. #1100 Los Angeles, CA 90010 OWNER’S Robert Chattel REPRESENTATIVE: Chattel Architecture, Planning, and Preservation 13417 Ventura Blvd. Sherman Oaks, CA 94123 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10(c)4 because the application and accompanying photo documentation suggest the submittal may warrant further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. S. GAIL GOLDBERG, AICP Director of Planning [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Lambert M. Giessinger, Preservation Architect Office of Historic Resources Office of Historic Resources Prepared by: [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] ________________________ Edgar Garcia, Preservation Planner Office of Historic Resources Attachments: November, 2008 Historic-Cultural Monument Application ZIMAS Report 701 S. Hill Street. CHC-2008-4978-HCM Page 2 of 2 SUMMARY Built in 1929 and located in the downtown area, this 13-story commercial building exhibits character-defining features of Art Deco-Gothic architecture. -

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV Maps and Descriptions Denis White March 2020

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV maps and descriptions Denis White March 2020 (Image NOAA, Landsat, Copernicus; Presentation Google Earth) A contribution to the corpus of materials created by James Omernik and colleagues on the Ecological Regions of the United States, North America, and South America The page size for this document is 9 inches horizontal by 12 inches vertical. Table of Contents Content Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Geographic patterns in Minnesota 1 Geographic location and notable features 1 Climate 1 Elevation and topographic form, and physiography 2 Geology 2 Soils 3 Presettlement vegetation 3 Land use and land cover 4 Lakes, rivers, and watersheds; water quality 4 Flora and fauna 4 3. Methods of geographic regionalization 5 4. Development of Level IV ecoregions 6 5. Descriptions of Level III and Level IV ecoregions 7 46. Northern Glaciated Plains 8 46e. Tewaukon/BigStone Stagnation Moraine 8 46k. Prairie Coteau 8 46l. Prairie Coteau Escarpment 8 46m. Big Sioux Basin 8 46o. Minnesota River Prairie 9 47. Western Corn Belt Plains 9 47a. Loess Prairies 9 47b. Des Moines Lobe 9 47c. Eastern Iowa and Minnesota Drift Plains 9 47g. Lower St. Croix and Vermillion Valleys 10 48. Lake Agassiz Plain 10 48a. Glacial Lake Agassiz Basin 10 48b. Beach Ridges and Sand Deltas 10 48d. Lake Agassiz Plains 10 49. Northern Minnesota Wetlands 11 49a. Peatlands 11 49b. Forested Lake Plains 11 50. Northern Lakes and Forests 11 50a. Lake Superior Clay Plain 12 50b. Minnesota/Wisconsin Upland Till Plain 12 50m. Mesabi Range 12 50n. Boundary Lakes and Hills 12 50o. -

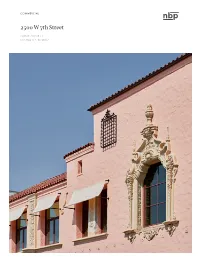

2500 W 7Th Street

COMMERCIAL 2500 W 7th Street 2500 W 7TH STREET LOS ANGELES, CA 90057 PROPERTY AT A GLANCE Building Size Lot Size 20,000 SQ. FT. 13,939 SQ. FT. Floors Year Built 2 1924 Walk Score Transit Score 95 82 FEATURED AMENITIES Commune-designed details Polished concrete and wood Fully approved Type-47 CUB with seating for flooring throughout throughout 167 including an exclusive outdoor patio _____ _____ _____ 9- to 15-foot ceiling heights. On-street parking and at surrounding public Custom wood windows and door _____ lots _____ ____ 2500 W 7th Street HISTORIC BUILDING CONVERTED TO CREATIVE OFFICE SPACE Completed in 1924 in the Spanish Colonial Revival style The building has been completely renovated while by architect Everett H. Merrill, 2500 W 7th St is one of maintaining its historic character and detailing. Restored Macarthur Park's most architecturally stunning buildings. A architectural features include the Churrigueresque detailing recently completed restoration and building modernization around the windows and main entrance way. underscores the building's historic character. Anchor tenants at 2500 W 7th St include Macarthur Park mainstays Aardvark Letterpress—celebrating their 50th anniversary in 2020; and paper supply shop McManus & Morgan (established 1923). LOCATION HIGHLIGHTS Westlake / Macarthur Park’s story goes back to the late 1800s. The neighborhood’s park was built around a reservoir that was connected to the LA River. By the 1920s, West 7th St had developed into one of LA's first high-end shopping districts. Today, Macarthur Park’s diverse immigrant culture is thriving alongside new development as well as a newfound interest in revitalizing the neighborhood's landmark buildings including the Hayworth Theatre and the Macarthur / Park Plaza. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: an Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 1 1976 The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865 Robert J. Sheran Timothy J. Baland Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Sheran, Robert J. and Baland, Timothy J. (1976) "The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An Informal Legal History of the Years 1835 to 1865," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Sheran and Baland: The Law, Courts and Lawyers in the Frontier Days of Minnesota: An THE LAW, COURTS, AND LAWYERS IN THE FRONTIER DAYS OF MINNESOTA: AN INFORMAL LEGAL HISTORY OF THE YEARS 1835 TO 1865* By ROBERT J. SHERANt Chief Justice, Minnesota Supreme Court and Timothy J. Balandtt In this article Chief Justice Sheran and Mr. Baland trace the early history of the legal system in Minnesota. The formative years of the Minnesota court system and the individuals and events which shaped them are discussed with an eye towards the lasting contributionswhich they made to the system of today in this, our Bicentennialyear. -

Analysis and Evaluation of the Spatial Structure of Cittaslow Towns on the Example of Selected Regions in Central Italy and North-Eastern Poland

land Article Analysis and Evaluation of the Spatial Structure of Cittaslow Towns on the Example of Selected Regions in Central Italy and North-Eastern Poland Marek Zagroba , Katarzyna Pawlewicz and Adam Senetra * Department of Socio-Economic Geography, Faculty of Geoengineering, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Prawoche´nskiego15, 10-720 Olsztyn, Poland; [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (K.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-89-5234948 Abstract: Cittaslow International promotes harmonious development of small towns based on sustainable relationships between economic growth, protection of local traditions, cultural heritage and the environment, and an improvement in the quality of local life. The aim of this study was to analyze and evaluate the differences and similarities in the spatial structure of Cittaslow towns in the Italian regions of Tuscany and Umbria and the Polish region of Warmia and Mazury. The study examined historical towns which are situated in different parts of Europe and have evolved in different cultural and natural environments. The presented research attempts to determine whether the spatial structure of historical towns established in different European regions promotes the dissemination of the Cittaslow philosophy and the adoption of sustainable development principles. The urban design, architectural features and the composition of urban and architectural factors which Citation: Zagroba, M.; are largely responsible for perceptions of multi-dimensional space were evaluated. These goals were Pawlewicz, K.; Senetra, A. Analysis achieved with the use of a self-designed research method which supported a subjective evaluation and Evaluation of the Spatial of spatial structure defined by historical urban planning and architectural solutions. -

Guide to a Microfilm Edition of the Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records

-~-----', Guide to a Microfilm Edition of The Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records Helen McCann White Minnesota Historical Society . St. Paul . 1974 -------~-~~~~----~! Copyright. 1974 @by the Minnesota Historical Society Library of Congress Catalog Number:74-10395 International Standard Book Number:O-87351-091-7 This pamphlet and the microfilm edition of the Alexander Ramsey Papers and Records which it describes were made possible by a grant of funds from the National Historical Publications Commission to the Minnesota Historical Society. Introduction THE PAPERS AND OFFICIAL RECORDS of Alexander Ramsey are the sixth collection to be microfilmed by the Minnesota Historical Society under a grant of funds from the National Historical Publications Commission. They document the career of a man who may be charac terized as a 19th-century urban pioneer par excellence. Ramsey arrived in May, 1849, at the raw settlement of St. Paul in Minne sota Territory to assume his duties as its first territorial gov ernor. The 33-year-old Pennsylvanian took to the frontier his family, his education, and his political experience and built a good life there. Before he went to Minnesota, Ramsey had attended college for a time, taught school, studied law, and practiced his profession off and on for ten years. His political skills had been acquired in the Pennsylvania legislature and in the U.S. Congress, where he developed a subtlety and sophistication in politics that he used to lead the development of his adopted city and state. Ram sey1s papers and records reveal him as a down-to-earth, no-non sense man, serving with dignity throughout his career in the U.S. -

Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context, 1837 to 1975

SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota May 2017 SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota MnHPO File No. Pending 106 Group Project No. 2206 SUBMITTED TO: Aurora Saint Anthony Neighborhood Development Corporation 774 University Avenue Saint Paul, MN 55104 SUBMITTED BY: 106 Group 1295 Bandana Blvd. #335 Saint Paul, MN 55108 PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Nicole Foss, M.A. REPORT AUTHORS: Nicole Foss, M.A. Kelly Wilder, J.D. May 2016 This project has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society. Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context ABSTRACT Saint Paul’s African American community is long established—rooted, yet dynamic. From their beginnings, Blacks in Minnesota have had tremendous impact on the state’s economy, culture, and political development. Although there has been an African American presence in Saint Paul for more than 150 years, adequate research has not been completed to account for and protect sites with significance to the community. One of the objectives outlined in the City of Saint Paul’s 2009 Historic Preservation Plan is the development of historic contexts “for the most threatened resource types and areas,” including immigrant and ethnic communities (City of Saint Paul 2009:12). The primary objective for development of this Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context Project (Context Study) was to lay a solid foundation for identification of key sites of historic significance and advancing preservation of these sites and the community’s stories. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Historic Preservation Planning Into the Broader Public Policy, Land Use • H - Housing Plan; Planning and Decision-Making Processes of the City

HISTORIC PRESERVATION The numbered strategies, policies, figures, and pages in the citywide Table of Contents plans of the Saint Paul Comprehensive Plan all employ the following Introduction.........................................................................................................................HP-1 abbreviations as a prefix to distinguish among these elements of the other citywide plans: Strategy 1: Be a Leader for Historic Preservation in Saint Paul.......................................................HP-8 • IN - introduction; Strategy 2: • LU - Land Use Plan; Integrate Historic Preservation Planning into the Broader Public Policy, Land Use • H - Housing Plan; Planning and Decision-Making Processes of the City................................................HP-11 • HP - Historic Preservation Plan; Strategy 3: • PR - Parks and Recreation Plan; Identify, Evaluate and Designate Historic Resources.................................................HP-13 • T - Transportation Plan; Strategy 4: • W - Water Resources Management Preserve and Protect Historic Resources.......................................................................HP-17 Plan; and • IM - Implementation. Strategy 5: Use Historic Preservation to Further Economic Development and Sustainability...HP-20 Strategy 6: Preserve Areas with Unique Architectural, Urban and Spatial Characteristics that Enhance the Character of the Built Environment.......................................................HP-24 Strategy 7: Provide Opportunities for Education and Outreach..................................................HP-26