USENIX December Proof 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIT—A Stupid Content Tracker

GIT—A Stupid Content Tracker Junio C. Hamano Twin Sun, Inc. [email protected] Abstract The paper gives an overview of how git evolved and discusses the strengths and weaknesses of its design. Git was hurriedly hacked together by Linus Torvalds, after the Linux kernel project lost its license to use BitKeeper as its source code management system (SCM). It has since 1 Low level design quickly grown to become capable of managing the Linux kernel project source code. Other projects have started to replace their existing Git is a “stupid content tracker.” It is designed SCMs with it. to record and compare the whole tree states ef- ficiently. Unlike traditional source code control Among interesting things that it does are: systems, its data structures are not geared to- ward recording changes between revisions, but for making it efficient to retrieve the state of in- 1. giving a quick whole-tree diff, dividual revisions. 2. quick, simple, stupid-but-safe merge, The unit in git storage is an object. It records: 3. facilitating e-mail based patch exchange workflow, and • blob – the contents of a file (either the 4. helping to pin-point the change that caused contents of a regular file, or the path a particular bug by a bisection search in pointed at by a symbolic link). the development history. • tree – the contents of a directory, by recording the mapping from names to ob- The core git functionality is implemented as a jects (either a blob object or a tree object set of programs to allow higher-layer systems that represents a subdirectory). -

Bazaar, Das DVCS

Bazaar, das DVCS Marek Kubica 20. November 2008 Marek Kubica Bazaar, das DVCS Vorweg ein paar Infos Mit was ich so spiele Bazaar in der Arbeit Mercurial für Python-Projekte Git für den Rest Welche Spielzeuge lass ich links liegen CVS wozu noch wo es SVN gibt? SVN wozu noch wenn es DVCS gibt? darcs lohnt sich nicht mehr monotone, codeville, arch obsolete das selbsgehackte, tolle DVCS deines Nachbarn ;) Marek Kubica Bazaar, das DVCS Geschichte In the beginning, there was GNU Arch Marek Kubica Bazaar, das DVCS GNU Arch Die Anfänge von DVCS CVS stinkt, wir brauchen was besseres SVN ist Evolution, keine Revolution GNU Arch war das erste DVCS mit dem ich in Kontakt kam (larch) fürchterlich kompliziert wurde dann von tla ersetzt immer noch fürchterlich Canonical hat tla 1.2 geforkt und Bazaar, baz genannt Paralell dazu: revc = Arch 2.0 Marek Kubica Bazaar, das DVCS Baz als Rettung? Von heiÿen Kartoeln baz war in C Was passiert: Canonical ruft Bazaar-NG ins Leben, bzr, lässt baz fallen Bazaar-NG wird in Bazaar umgetauft baz ist tot, tla ist tot, larch ist tot, revc ist bedeutungslos Hurra, GNU Arch ist endlich tot, es lebe bzr! Marek Kubica Bazaar, das DVCS bzr, der Retter Was bietet Bazaar? in Python geschrieben, mit einigen Speedups in Pyrex (C) reguläre Releases (quasi jeden Monat) Einfache Bedienung Meist ausreichende Performance Umfangreiche Dokumentation: Programmmeldungen, Manpages, Wiki, IRC-Channel (wenn man Geduld hat) Flexible Einsatzmöglichkeiten (verschiedene Workows) 1 Git mit Bazaar simulieren 2 SVN in Bazaar nachbauen (für Nostalgiker) freier Hoster wo man Code hochladen kann (Launchpad) Marek Kubica Bazaar, das DVCS Zeitleiste 2005 war eine aufregende Zeit 26. -

Analysis and Comparison of Distributed Version Control Systems

Fachhochschul-Bachelorstudiengang SOFTWARE ENGINEERING A-4232 Hagenberg, Austria Analysis and Comparison of Distributed Version Control Systems Bachelorarbeit Teil 1 zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Bachelor of Science in Engineering Eingereicht von Daniel Knittl-Frank Begutachter: DI Dr. Stefan Wagner Hagenberg, Juni 2010 Contents Abstract iii Kurzfassung iv 1 Introduction1 1.1 Motivation............................1 1.2 Goals...............................2 1.3 Content..............................2 2 Version Control in General3 2.1 Workflows.............................4 2.2 Foundations............................5 2.2.1 Glossary..........................5 2.2.2 Repository........................6 2.2.3 Working Directory....................7 2.2.4 Diff and Patch......................7 2.2.5 Merge...........................9 2.2.6 Mainline, Branches and Tags.............. 12 3 Centralized Version Control 14 3.1 Tools................................ 14 3.1.1 CVS............................ 14 3.1.2 Subversion........................ 15 4 Distributed Version Control 17 4.1 Differences............................. 17 4.2 Concepts............................. 19 4.2.1 Revision identifiers.................... 20 4.2.2 Integrity.......................... 20 4.2.3 History representation.................. 21 4.3 Tools................................ 21 4.3.1 Bazaar........................... 22 4.3.2 Git............................. 27 4.3.3 Mercurial......................... 32 i Contents ii 5 Comparison 38 5.1 Testing Scenario......................... 38 5.2 Results............................... 38 6 Conclusion 46 Abstract Version and configuration control systems have played an essential role in software development for the last decades. Starting with the new millennium a new trend surfaced, distributed version control: dedicated central servers for few authorized users lose importance in favor of a more dynamic workflow, in which every developer works with a copy of a project's complete history and changes are synchronized ad-hoc between developers. -

Linux-Cookbook.Pdf

LINUX COOKBOOK ™ Other Linux resources from O’Reilly Related titles Linux Device Drivers Exploring the JDS Linux Linux in a Nutshell Desktop Running Linux Learning Red Hat Enterprise Building Embedded Linux Linux and Fedora Systems Linux Pocket Guide Linux Security Cookbook Understanding the Linux Kernel Linux Books linux.oreilly.com is a complete catalog of O’Reilly’s books on Resource Center Linux and Unix and related technologies, including sample chapters and code examples. ONLamp.com is the premier site for the open source web plat- form: Linux, Apache, MySQL, and either Perl, Python, or PHP. Conferences O’Reilly brings diverse innovators together to nurture the ideas that spark revolutionary industries. We specialize in document- ing the latest tools and systems, translating the innovator’s knowledge into useful skills for those in the trenches. Visit conferences.oreilly.com for our upcoming events. Safari Bookshelf (safari.oreilly.com) is the premier online refer- ence library for programmers and IT professionals. Conduct searches across more than 1,000 books. Subscribers can zero in on answers to time-critical questions in a matter of seconds. Read the books on your Bookshelf from cover to cover or sim- ply flip to the page you need. Try it today with a free trial. LINUX COOKBOOK ™ Carla Schroder Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Paris • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Linux Cookbook™ by Carla Schroder Copyright © 2005 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. -

SCM: a Look at Scons and GNU Arch

SCM: A look at SCons and GNU Arch ¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ Ben Leslie ¦ § ¡ ¨ © ¢ § ¨ ¡ © ¨ © 1 WHAT IS SCM? CM is the discpline of controlling the evolution of complex systems; SCM is its specialization for computer programs and associated documents WHAT IS SCM? 2 WHAT IS SCM? CM is the discpline of controlling the evolution of complex systems; SCM is its specialization for computer programs and associated documents No really, what is it ? WHAT IS SCM? 2-A WHAT IS SCM? CM is the discpline of controlling the evolution of complex systems; SCM is its specialization for computer programs and associated documents No really, what is it ? • Versioning WHAT IS SCM? 2-B WHAT IS SCM? CM is the discpline of controlling the evolution of complex systems; SCM is its specialization for computer programs and associated documents No really, what is it ? • Versioning • Building WHAT IS SCM? 2-C BUILD SYSTEM – PURPOSE Automate construction process • Build rules – how to change .c into .o • Capture all build rules Rebuild exactly what is needed BUILD SYSTEM – PURPOSE 3 BUILD SYSTEM – PURPOSE Automate construction process • Build rules – how to change .c into .o • Capture all build rules Rebuild exactly what is needed • Build everything required – correctness. BUILD SYSTEM – PURPOSE 3-A BUILD SYSTEM – PURPOSE Automate construction process • Build rules – how to change .c into .o • Capture all build rules Rebuild exactly what is needed • Build everything required – correctness. • Don’t build anymore then needed – performance. BUILD SYSTEM – PURPOSE 3-B BUILD SYSTEM – PURPOSE Automate construction process • Build rules – how to change .c into .o • Capture all build rules Rebuild exactly what is needed • Build everything required – correctness. -

Git and Gerrit in Action and Lessons Learned Along the Path to Distributed Version Control

Git and Gerrit in Action And lessons learned along the path to distributed version control Chris Aniszczyk (Red Hat) Principal Software Engineer [email protected] http://aniszczyk.org About Me I've been using and hacking open source for ~12 years - contribute{d} to Gentoo Linux, Fedora Linux, Eclipse Hack on Eclipse, Git and other things at Red Hat Member of the Eclipse Board of Directors Member in the Eclipse Architecture Council I like to run! (2 mins short of Boston qualifying ;/) Co-author of RCP Book (www.eclipsercp.org) An Introduction to Git and Gerrit | © 2011 by Chris Aniszczyk Agenda History of Version Control (VCS) The Rise of Distributed Version Control (DVCS) Code Review with Git and Gerrit Lessons Learned at Eclipse moving to a DVCS Conclusion Q&A An Introduction to Git and Gerrit | © 2011 by Chris Aniszczyk Version Control Version Control Systems manage change “The only constant is change” (Heraclitus) An Introduction to Git and Gerrit | © 2011 by Chris Aniszczyk Why Version Control? VCS became essential to software development because: They allow teams to collaborate They manage change and allow for inspection They track ownership They track evolution of changes They allow for branching They allow for continuous integration An Introduction to Git and Gerrit | © 2011 by Chris Aniszczyk Version Control: The Ancients 1972 – Source Code Control System (SCCS) Born out of Bell Labs, based on interleaved deltas No open source implementations as far as I know 1982 – Revision Control System (RCS) Released as an alternative to SCCS -

A Technical Summary

A Technical Summary Table A.1. Kerberos administrative ACL (MIT) Allow Deny Operation a A Add principals or policies d D Delete principals or policies m M Modify principals or policies c C Change passwords i I Inquiry the database l L List principals or policies s S Set key for principals * or x Allow all privileges Table A.2. Kerberos kadmin password policies (MIT) Option Meaning -history Minimum count of unusable old passwords -maxlife Maximum allowed lifetime -minclasses Minimum character classes -minlength Minimum password length -minlife Minimum lifetime 380 A Technical Summary Table A.3. LDAP access control list levels Level Privilege Coding Explanation none =0 No access at all auth =x Permits authentication attempt compare =cx Permits comparison search =scx Permits search filter application read =rscx Permits search result inspection write =wrscx Permits modification or deletion Table A.4. The OpenAFS access control list attributes Permission Meaning l List contents (lookup) i Create new files or directories (insert) d Delete files or directories a Change ACL attributes of directories (administer) r Read contents of files w Modify contents of files (write) k Lock files for reading read Equivalent to rl write Equivalent to rlidwk (no administrative rights) all Equivalent to rlidwka none Remove all ACL permissions Table A.5. The OpenAFS @sys names (excerpt) @sys Architecture alpha dux40 Digital UNIX 4 on an Alpha alpha dux50 Digital UNIX 5 on an Alpha i386 linux24 Linux Kernel 2.4 on Intel and compatible i386 linux26 Linux Kernel 2.6 on Intel and compatible i386 nt40 Microsoft Windows NT and later on Intel and compatible ppc darwin70 Apple MacOS X 10.3 on a PowerPC Macintosh ppc darwin80 Apple MacOS X 10.4 on a PowerPC Macintosh ppc darwin90 Apple MacOS X 10.5 on a PowerPC Macintosh rs aix52 IBM AIX 5.2 on a pSeries rs aix53 IBM AIX 5.3 on a pSeries sgi 65 SGI Irix 6.5 on a MPIS x86 darwin80 Apple MacOS X 10.4 on an Intel Macintosh x86 darwin90 Apple MacOS X 10.5 on an Intel Macintosh A Technical Summary 381 Table A.6. -

Storage Tradeoffs in a Collaborative Backup Service for Mobile Devices Ludovic Courtès, Marc-Olivier Killijian, David Powell

Storage Tradeoffs in a Collaborative Backup Service for Mobile Devices Ludovic Courtès, Marc-Olivier Killijian, David Powell To cite this version: Ludovic Courtès, Marc-Olivier Killijian, David Powell. Storage Tradeoffs in a Collaborative Backup Service for Mobile Devices. 2006. hal-00187069 HAL Id: hal-00187069 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00187069 Preprint submitted on 13 Nov 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Storage Tradeoffs in a Collaborative Backup Service for Mobile Devices† Ludovic Courtès Marc-Olivier Killijian David Powell fi[email protected] LAAS-CNRS 7 avenue du Colonel Roche 31077 Toulouse cedex 4 France Abstract Our goal is to leverage the ubiquity of communicat- ing mobile devices to implement a collaborative backup service. In such a system,devices participating in the ser- Mobile devices are increasingly relied on but are vice would be able to use other devices’storage to back used in contexts that put them at risk of physical dam- up their own data. Of course, each device would have to age, loss or theft. We consider a fault-tolerance ap- contribute some of its own storage resources for others proach that exploits spontaneous interactions to imple- to be able to benefit from the service. -

Storage Tradeoffs in a Collaborative Backup Service for Mobile Devices Ludovic Courtès, Marc-Olivier Killijian, David Powell

Storage Tradeoffs in a Collaborative Backup Service for Mobile Devices Ludovic Courtès, Marc-Olivier Killijian, David Powell To cite this version: Ludovic Courtès, Marc-Olivier Killijian, David Powell. Storage Tradeoffs in a Collaborative Backup Service for Mobile Devices. 2006. hal-00187069 HAL Id: hal-00187069 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00187069 Preprint submitted on 13 Nov 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Storage Tradeoffs in a Collaborative Backup Service for Mobile Devices† Ludovic Courtès Marc-Olivier Killijian David Powell fi[email protected] LAAS-CNRS 7 avenue du Colonel Roche 31077 Toulouse cedex 4 France Abstract Our goal is to leverage the ubiquity of communicat- ing mobile devices to implement a collaborative backup service. In such a system,devices participating in the ser- Mobile devices are increasingly relied on but are vice would be able to use other devices’storage to back used in contexts that put them at risk of physical dam- up their own data. Of course, each device would have to age, loss or theft. We consider a fault-tolerance ap- contribute some of its own storage resources for others proach that exploits spontaneous interactions to imple- to be able to benefit from the service. -

Bill Laboon Friendly Introduction Version Control: a Brief History

Git and GitHub: A Bill Laboon Friendly Introduction Version Control: A Brief History ❖ In the old days, you could make a copy of your code at a certain point, and release it ❖ You could then continue working on your code, adding features, fixing bugs, etc. ❖ But this had several problems! VERSION 1 VERSION 2 Version Control: A Brief History ❖ Working with others was difficult - if you both modified the same file, it could be very difficult to fix! ❖ Reviewing changes from “Release n” to “Release n + 1” could be very time-consuming, if not impossible ❖ Modifying code locally meant that a crash could take out much of your work Version Control: A Brief History ❖ So now we have version control - a way to manage our source code in a regular way. ❖ We can tag releases without making a copy ❖ We can have numerous “save points” in case our modifications need to be unwound ❖ We can easily distribute our code across multiple machines ❖ We can easily merge work from different people to the same codebase Version Control ❖ There are many kinds of version control out there: ❖ BitKeeper, Perforce, Subversion, Visual SourceSafe, Mercurial, IBM ClearCase, AccuRev, AutoDesk Vault, Team Concert, Vesta, CVSNT, OpenCVS, Aegis, ArX, Darcs, Fossil, GNU Arch, BitKeeper, Code Co-Op, Plastic, StarTeam, MKS Integrity, Team Foundation Server, PVCS, DCVS, StarTeam, Veracity, Razor, Sun TeamWare, Code Co-Op, SVK, Fossil, Codeville, Bazaar…. ❖ But we will discuss git and its most popular repository hosting service, GitHub What is git? ❖ Developed by Linus Torvalds ❖ Strong support for distributed development ❖ Very fast ❖ Very efficient ❖ Very resistant against data corruption ❖ Makes branching and merging easy ❖ Can run over various protocols Git and GitHub ❖ git != GitHub ❖ git is the software itself - GitHub is just a place to store it, and some web-based tools to help with development. -

Recruiting Source Special Form of Software Development Method Used in XTLA

Recruiting Source Special Form of Software Development Method Used in XTLA Masatake YAMATO Translated by Ryoko YAMATO Ideal Open Source Development ● Attracts many developers and users, which leads to the project growth. ● Ideal growing cycle: 1.First, source code is open to public. 2.Developers begin to join the project. 3.Functions and quality are improved. 4.Increase in the number of users catches the eyes of other developers. 5.More developers will join the project. 6.More users, as a result. Open Source Development in Reality ● Too many projects for the number of developers on earth. – The number of developers per project will not increase. – The number of users per project will not increase either. – Another similar project to be started by others; since the existence of the initial project is hardly known to people. – Similar projects fight over developers and users. – Each similar project is likely to remain imperfect. ● The whole category, which these projects belongs to, might fade. Ideal Project Project leader Developers Users Dead-end Project Project leader = Developer = User Ideal Category Project B Project A Project C Mutual growth by competing each other Dead-end Category ● Users can©t easily see which one is the best to try. ● Many projects are not ready for practical use. ● Developers can©t see which project they should compete with. Dead-end Category Even if you start another project to overcome the situation, your project will be hardly recognized in too many projects. Example of Dead-end Category : IDE In case you don©t know Eclipse, you have to check all 519 projects. -

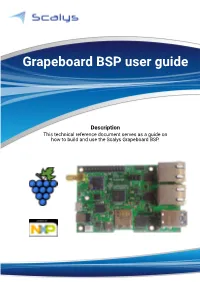

Grapeboard BSP User Guide

1 Grapeboard BSP user guide Description This technical reference document serves as a guide on how to build and use the Scalys Grapeboard BSP. www.scalys.com Introduction This document serves as a technical reference document on how to build the Board Support Package (BSP) for Scalys Grapeboard. It is meant to supplement the available documentation already provided by NXP[1,2]. Note that Grapeboard shares hardware platform with Scalys TrustBox. Due to it, this manual describes a TrustBox BSP build procedure. The build products will work both on TrustBox and Grapeboard. Grapeboard features a QorIQ LS1012A processor[3] that contains a single Arm Cortex-A53 core. NXP provides two flavours of BSP for this specific processor. The first being the Yocto based Linux Software Development Kit (SDK) for QorIQ processors and the second flavour is the more recently introduced Layerscape Software Development Kit (LSDK). The QorIQ Linux SDK is based the Yocto Project [4], whilst the LSDK is based on a more disaggregated flex-building environment [5]. This document assumes the reader has a basic knowledge of platform software and deploy- ment, and it will not go into too much detail of the actions performed to build the BSPs. This document currently only describes building the BSP through the LSDK method. Contact Scalys for more information on the Yocto based SDK. Additionally, NXP intends to update the LSDK reg- ularly, however this document only focusses on a specific release version. Contact Scalys when updates are desired. Rev Date Description 1.5 10thJun, 2019 RCW section changes 1.4 29thMay, Improved document structure 2019 1.3 4thMay, 2019 Updated in accordance with new lsdk19.03 1.2 18thOct, 2018 URL and FAQ update 1.1 28thMay, FAQ update 2018 1.0 18thMay, 2018 First release Copyright © 2019, Scalys BV Restricted 2 BSP User guide www.scalys.com September 2019 Contents List of Tables 4 1 Preparation 5 1.1 Install the dependencies using the package manager................