The Myth of Menstruation: How Menstrual Regulation and Suppression Impact Contraceptive Choice Andrea L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Menstrual Suppression in Gender Minority Youth

DOI: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2021.2020.0283 Case report Menstrual Suppression in Gender Minority Youth Short title: Menstrual suppression for transmales Sinem Akgül1, Zeynep Tüzün2, Melis Pehlivantürk Kızılkan3, Zeynep Alev Ozon4 1Hacettepe University, Ihsan Dogramaci Children’s Hospital, Department of Pediatrics Division of Adolescent Medicine, Ankara, Turkey 2Hacettepe University, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Adolescent Medicine 3Hacettepe University, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Adolescent Medicine 4Hacettepe University, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Endocrinology This case series was presented as a short oral presentation at the XXIV. National Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes Congress. 30th October- 1st November 2020 What is already known on this topic? Menstrual distress is frequently reported in Gender Minority Youth (GMY). Menstrual suppression refers to the practice of using hormonal management to reduce menstrual bleeding which may be an option to treat menstrual dysphoria in GMY. What this study adds? Menstrual suppression should be offered to GMY when pubertal suppression is not an option. Each treatment plan should be individualized. Abstract The purpose of this case series was to evaluate menstrual suppression in sex assigned at birth female adolescents identifying as male or gender non-conforming. A retrospective chart review of 4 gender minority youth (GMY), age 14–17, was performed for gender identity history, type and success of menstrual suppression, method satisfaction, side effects and improvement in menstrual distress. Menstrual suppression was successful in 3 patients, one patient discontinued use due to side effects that caused an increase in gender dysphoria. Menstrual distress and bleeding pattern improved in the majority of GMY in this series but side effects, as well as contraindications, may limit their use. -

A Scoping Review on Women's Responses to Contraceptive

Polis et al. Reproductive Health (2018) 15:114 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0561-0 REVIEW Open Access There might be blood: a scoping review on women’s responses to contraceptive- induced menstrual bleeding changes Chelsea B. Polis* , Rubina Hussain and Amanda Berry Abstract Introduction: Concern about side effects and health issues are common reasons for contraceptive non-use or discontinuation. Contraceptive-induced menstrual bleeding changes (CIMBCs) are linked to these concerns. Research on women’s responses to CIMBCs has not been mapped or summarized in a systematic scoping review. Methods: We conducted a systematic scoping review of data on women’s responses to CIMBCs in peer-reviewed, English-language publications in the last 15 years. Investigator dyads abstracted information from relevant studies on pre-specified and emergent themes using a standardized form. We held an expert consultation to obtain critical input. We provide recommendations for researchers, contraceptive counselors, and product developers. Results: We identified 100 relevant studies. All world regions were represented (except Antarctica), including Africa (11%), the Americas (32%), Asia (7%), Europe (20%), and Oceania (6%). We summarize findings pertinent to five thematic areas: women’s responses to contraceptive-induced non-standard bleeding patterns; CIMBCs influence on non-use, dissatisfaction or discontinuation; conceptual linkages between CIMBCs and health; women’sresponsesto menstrual suppression; and other emergent themes. Women’s preferences for non-monthly bleeding patterns ranged widely, though amenorrhea appears most acceptable in the Americas and Europe. Multiple studies reported CIMBCs as top reasons for contraceptive dissatisfaction and discontinuation; others suggested disruption of regular bleeding patterns was associated with non-use. -

Menstrual Suppression in an Adolescent with Intellectual Disability

On the case... Menstrual suppression in an adolescent with intellectual disability By Casey S. Hopkins, PhD, RN, WHNP-BC bby is a 12-year-old girl to be right around the corner. Liz individualized education plan and is with an autism spectrum expressed her concern about Abby in a special education class. She lives Adisorder, attention-deficit/ being able to handle her periods on at home with her mother, father, and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and her own. The pediatrician referred older sister. intellectual disability (ID). She pres- them to the nurse practitioner at the Liz expresses her concerns to the ents to the pediatric and adolescent PAG office to discuss preparation for nurse practitioner (NP) regarding gynecology (PAG) office with her and management of menstruation. menstruation and how Abby will mother, Liz. Abby has not yet started Abby is currently taking methyl- cope with it. She is concerned that having periods. Liz noticed Abby’s phenidate 36 mg daily for treatment Abby will not understand what is breasts began to develop about of ADHD. She is communicative happening when menstrual bleeding a year and a half ago, and Abby verbally. Liz reports Abby functions occurs. She worries that Abby will has recently had a growth spurt in cognitively at about the level of experience pain with menses and height. The pediatrician mentioned a 7-year-old child. Abby attends may not be able to communicate at Abby’s well-child appointment school daily and enjoys her friends effectively regarding the pain. Liz last month that menarche was likely and teachers at school. -

Menstrual Suppression in Adolescent Females with Intellectual Disability

Menstrual suppression Macey & Omar Dynamics of Human Health; 2020:7(1) ISSN 2382-1019 Menstrual Suppression in Adolescent Females with Intellectual Disability Macey Johnson & Hatim Omar Division of Adolescent medicine, Kentucky University, USA Corresponding author: Prof Hatim Omar, e-mail: [email protected] Received: 29/1/2020; revised 25/2/2020; Accepted: 3/3/2020 [citation: Johnson, Macey. & Omar, Hatim. (2020). Menstrual Suppression in Adolescent Females with Intellectual Disability. DHH, 7(1):https://journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=2060]. Introduction When caring for adolescent females who have an intellectual disability (ID), a variety of factors must be considered that may not be implicated in other patients. One of these is the complex reproductive and sexual function needs of these patients. More specifically, menstruation brings challenges with these patients due to a variety of factors that will be discussed throughout this article. The caregivers of these patients may seek medical advice for ways to manage menstruation and alleviate symptoms for the patient. If these patients experience mild symptoms of menstruation, education and reassurance can be an effective way to treat these symptoms. Many of these girls are able to manage proper hygiene without help from caregivers once this education and reassurance occurs [18]. For those adolescent girls with more severe symptoms or those who are unable to manage menses on their own, menstrual suppression can be effective. Menstrual suppression has been an option for those adolescent girls with ID whose caregivers feel that menstruation brings physical and psychological challenges to the adolescents as well as themselves, and that the adolescents would experience a benefit or increased quality of life if it is suppressed. -

Menstrual Suppression: Current Perspectives

International Journal of Women’s Health Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Menstrual suppression: current perspectives Paula Adams Hillard Abstract: Menstrual suppression to provide relief of menstrual-related symptoms or to manage Department of Obstetrics and medical conditions associated with menstrual morbidity or menstrual exacerbation has been used Gynecology, Stanford University clinically since the development of steroid hormonal therapies. Options range from the extended School of Medicine, Stanford, or continuous use of combined hormonal oral contraceptives, to the use of combined hormonal CA, USA patches and rings, progestins given in a variety of formulations from intramuscular injection to oral therapies to intrauterine devices, and other agents such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists. The agents used for menstrual suppression have variable rates of success in inducing amenorrhea, but typically have increasing rates of amenorrhea over time. Therapy may be limited by side effects, most commonly irregular, unscheduled bleeding. These therapies For personal use only. can benefit women’s quality of life, and by tabs ilizing the hormonal milieu, potentially improve the course of underlying medical conditions such as diabetes or a seizure disorder. This review addresses situations in which menstrual suppression may be of benefit, and lists options which have been successful in inducing medical amenorrhea. Keywords: menstrual molimena, amenorrhea, inducing amenorrhea, quality of life Background Suppression of menstrual periods to provide relief of menstrual-related symptoms has been used in a variety of medical conditions since the availability of steroid hormone therapy. This option has gained legitimacy through its use in treating symptoms, but is now being used more frequently by women for personal preference. -

More Than Menorrhagia

More Than Menorrhagia VIIA D. ANDERSON, APRN HEMATOLOGY NURSE PRACTITIONER JANE GEYER, APRN, WHNP-BC GYNECOLOGY NURSE PRACTITIONER Objectives Summarize menstrual physiology Define heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) Explain common bleeding disorders associated with HMB Describe the evaluation process of HMB and Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA) Introduce common pharmacologic agents used to control HMB and IDA Explain the TCH referral process for patients with HMB and IDA 13 yo obese female presents to PCP for annual visit History of migraines (with aura) well controlled with prn Imitrex History of epistaxis, but epistaxis occurring more frequently since starting softball Case Study: Last nosebleed 1 month ago while at the movies with her boyfriend Tiffany Menarche attained 6 months ago Menses occurs 1-2 times/month Menses 10 days in duration Temp 37C, HR 101, RR 18, BP 100/62 Pallor Fatigue Lab Normal Ranges Result WBC 4.5-13 6.49 Hemoglobin 12-16 gm/dl 7.5 gm/dl MCV 78-95 fl 69 fl Platelet 150-450 563 Lab Absolute Retic 0.042-0.065 0.026 Count UPT Negative Results PT 10.5-15.7 seconds 11 seconds PTT 25.2-33.2 seconds 38 seconds TSH 0.5-4.3 mIU/L 0.81 mIU/L Vwf antigen 56-176% 38% Vwf activity 50-150% 34% Factor 8 47-169% 35% Von Willebrand ratio 0.7-1.2 0.9 If you encounter abnormal labs you are not sure how to interpret………… Refer, Refer, Refer! We’re here to help! The Menstrual Phase 1: Follicular Phase Phase 2: Luteal Phase Cycle • Begins day 1 of the menstrual • Begins on the day of the LH cycle Surge • Ovarian follicle present typically The first day of menses represents the first day of a menstrual cycle. -

Menstrual Suppression • Options for Menstrual Suppression

To Bleed... Christina Davis-Kankanamge Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology Learning Objectives • Define abnormal uterine bleeding • Reasons for menstrual suppression • Options for menstrual suppression 1 Identification of abnormal menstrual patterns in adolescence may improve early identification of potential health concerns for adulthood. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding “outside of normal volume, duration, regularity, or frequency is considered abnormal uterine bleeding” excessive blood loss should be based on the patient’s perception Persistent anovulation is most frequent in the adolescent age group identification of abnormal menstrual patterns in adolescence may improve early identification of potential health concerns for adulthood 2 Menstrual Bleeding Normal Abnormal • Change of hygiene items every 1-2h • 3-6 hygiene items a day • Lasting more than 7d • Shorter interval than q21d or longer • Every 21-45d than 45d • <7d • Occur 90d apart even for one cycle • Are heavy and associated with excessive bruising/bleeding or a family history of bleeding d/o Menstrual Bleeding Normal Abnormal • 3-6 hygiene • Change of hygiene items every 1-2h items a day • Lasting more than 7d • Every 21-45d • Shorter interval than q21d or longer than 45d • <7d • Occur 90d apart even for one cycle • Are heavy and associated with excessive bruising/bleeding or a family history of bleeding d/o 3 … Or Not to Bleed Chimsom T. Oleka, MD, FACOG Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 4 ontact with the monthly flux of women turns new wine sour, makes crops wither, kills Cgrafts, dries seeds in gardens, causes the fruit of trees to fall off, dims the bright surface of mirrors, dulls the edge of steel and the gleam of ivory, kills bees, rusts iron and bronze, and causes a horrible smell to fill the air. -

Health Care Providers' Recommendations for Menstrual Suppression for Servicewomen Prior to Deploying to an Austere Field Envir

HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS’ RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MENSTRUAL SUPPRESSION FOR SERVICEWOMEN PRIOR TO DEPLOYING TO AN AUSTERE FIELD ENVIRONMENT By Megan A. Sherwood BSN, University of Alaska Anchorage, 2006 Submitted to the School of Nursing and The Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Nursing Practice. Karen K. Trees, DNP, RNC, CNM, WHCNP-BC, FNP-BC Faculty Capstone Project Committee, Co-Chair Janet D. Pierce, Ph.D., APRN, CCRN, FAAN Faculty Capstone Project Committee, Co-Chair Diane Mahoney, DNP, FNP-BC, WHNP-BC Committee Member 20 October 2017 Date Capstone Project Accepted The DNP Project committee for Megan A. Sherwood certifies that this is the approved version for the following DNP Project: Health Care Providers’ Recommendations for Menstrual Suppression for Servicewomen Prior to Deploying to an Austere Field Environment Karen K. Trees, DNP, RNC, CNM, WHCNP-BC, FNP-BC Faculty Capstone Project Committee, Co-Chair Janet D. Pierce, Ph.D., APRN, CCRN, FAAN Faculty Capstone Project Committee, Co-Chair Diane Mahoney, DNP, FNP-BC, WHNP-BC Committee Member Date Approved: 20 October 2017 1 HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS’ RECOMMENDATIONS FOR MENSTRUAL SUPPRESSION FOR SERVICEWOMEN PRIOR TO DEPLOYING TO AN AUSTERE FIELD ENVIRONMENT Megan A. Sherwood, BSN Specialty Area: Family Nurse Practitioner Committee Co-Chair: Dr. Karen K. Trees, DNP, RNC, CNM, WHCNP-BC, FNP-BC Committee Co-Chair: Dr. Janet D. Pierce, Ph.D., APRN, CCRN, FAAN Committee Member: Dr. Diane Mahoney, DNP, FNP-BC, WHNP-BC Problem: Servicewomen that are being deployed to austere field environments may need assistance in managing their menstrual hygiene. -

Menstrual Management for Adolescents with Disabilities Elisabeth H

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care Menstrual Management for Adolescents With Disabilities Elisabeth H. Quint, MD, Rebecca F. O’Brien, MD, COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE, The North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology The onset of menses for adolescents with physical or intellectual disabilities abstract can affect their independence and add additional concerns for families at home, in schools, and in other settings. The pediatrician is the primary health care provider to explore and assist with the pubertal transition and menstrual management. Menstrual management of both normal and abnormal cycles may be requested to minimize hygiene issues, This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have premenstrual symptoms, dysmenorrhea, heavy or irregular bleeding, fi led confl ict of interest statements with the American Academy contraception, and conditions exacerbated by the menstrual cycle. Several of Pediatrics. Any confl icts have been resolved through a process approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of options are available for menstrual management, depending on the outcome Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial that is desired, ranging from cycle regulation to complete amenorrhea. The involvement in the development of the content of this publication. use of medications or the request for surgeries to help with the menstrual Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefi t from expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external cycles in teenagers with disabilities has medical, social, legal, and ethical reviewers. However, clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics may not refl ect the views of the liaisons or the organizations implications. -

Missing Menses: Preventing the Menstrual Cycle and Emergent Therapy for Breakthrough Bleeding

9/13/2018 Pediatric Pharmacy Advocacy Group Missing Menses: Preventing the Menstrual Cycle and Emergent Therapy for Breakthrough Bleeding Tara Wright, PharmD, BCPPS Seattle Children’s Hospital Objectives • Identify gynecologic concerns in adolescent females undergoing cancer therapy • Summarize supportive care recommendations for a patient receiving leuprolide acetate • Discuss pros and cons of preventative therapies for menstrual suppression • Recognize therapies that can be utilized for emergent management of breakthrough bleeding Audience Experience • My institution has a guideline for managing menstrual suppression • I manage menstrual suppression regimens regularly 1 9/13/2018 Terminology Term Definition Amenorrhea No bleeding for ≥ 6 months in a nonmenopausal woman Menorrhagia Heavy regular menstrual cycles with heavy bleeding of > 80 mL or a duration of > 7 days Menometrorrhagia Excessive menstrual bleeding at regular intervals Metrorrhagia Bleeding between periods or irregular bleeding Oligomenorrhea Intermenstrual bleeding occurring at intervals > 35 days apart Polymenorrhea Menstrual bleeding occurring at intervals < 21 days apart Bates JS, et al. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1092-1110. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB) • Change in menstrual cycle, amount of blood loss, duration of flow, or menses frequency • AUB can significantly alter quality of life – 10-30% of women experience menorrhagia • 20% of ambulatory care visit due to menstruation issues • Among adolescents, 34-51% report experiencing oligomenorrhea and polymenorrhea Bates -

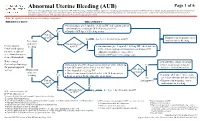

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB)

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB) Page 1 of 6 Disclaimer: This algorithm has been developed for MD Anderson using a multidisciplinary approach considering circumstances particular to MD Anderson’s specific patient population, services and structure, and clinical information. This is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of physicians or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient's care. This algorithm should not be used to treat pregnant women. Note: This algorithm is intended for use in hematologic malignancies PRESENTATION TREATMENT 2 ● On admission, give leuprolide 11.25 mg IM and continue patient on monophasic continuous OCP (skip placebo pills) 3 Yes ● Consider OCP taper if bleeding occurs Patient on OCP? Primary team to manage cancer See Page 2 for alternative to OCP Yes and monitor for bleeding Prevention No of uterine Contraindication4 2 Premenopausal bleeding to OCP? ● On admission, give leuprolide 11.25 mg IM , check baseline females undergoing LFTs, and start patient on monophasic continuous OCP 1 No intensive treatment (skip placebo pills), see Appendix A 3 (i.e., chemotherapy or ● Consider OCP taper if bleeding occurs stem cell transplant) Note: Consult ● Consult Gynecologic Oncology Gynecologic Oncology Immediately when bleeding occurs, perform all of the following: Yes ● Platelet transfusion if platelet 3 for post-menopausal ● Start OCP taper (three times a day for 3 days) level is < 20-30 K/microliter 2 Bleeding women Management -

Suppressing Or Delaying Menstruation Background

Suppressing or Delaying Menstruation Background Menstrual suppression involves the use of various medications or devices to decrease the frequency and volume of normal menses or to achieve therapeutic amenorrhea. There are many circumstances when a woman may want or need to suppress or temporarily delay menstruation.1,2 These reasons can be medical or simply due to personal preference. Some of the most common reasons include1-4: To reduce pain and discomfort (dysmenorrhea) associated with the menstrual cycle. To reduce pain (dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, or pelvic pain) associated with endometriosis. To reduce abnormal uterine bleeding (including bleeding due to fibroids). To reduce bleeding in women with hemorrhagic diatheses. To reduce hormone withdrawal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, breast tenderness, bloating, mood changes) associated with combined hormonal contraceptive hormone-free intervals. To reduce the frequency of migraines and headaches associated with menstruation. To reduce vasomotor symptoms and problematic bleeding in menopausal women taking combined hormonal contraceptives in their hormone free interval. To reduce the burden of menstruation for women with disabilities or undergoing cancer treatment. Personal preference (upcoming vacation, wedding, academic examination, athletic event, etc.). Medications Commonly Used to Suppress or Delay Menstruation: Combined Hormonal Contraceptives: No single regimen/product has been recognized as being superior to others. All currently available ethinyl estradiol contraceptives (oral [monophasic or multiphasic], transdermal, or vaginal) can be used in a continuous or extended regimen.3 The choice of monophasic or multiphasic oral contraceptive is often at the discretion of the prescriber.3 The patch may be preferred for patients with gastrointestinal issues or for those with poor adherence to daily oral contraceptives.