Perspectives on Arts Education and Curriculum Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Visual Art with the Brain in Mind

1 Teaching Visual Art with the Brain in Mind A thesis presented by Karen G. Pearson to the Graduate School of Education In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education In the field of Education College of Professional Studies Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts August 20, 2019 2 ABSTRACT Critical periods of perceptual development occur during the elementary and middle school years. Vision plays a major role in this development. The use of child development knowledge of Bruner, Skinner, Piaget and Inhelder coupled with the artistic thinking theories of Goldschmidt, Marshall, and Williams through and the lens of James J. Gibson and his ex-wife Eleanor J. framed the study. Sixteen 8-10-year-olds over eight one-hour weekly meetings focused on how they see and learn how to draw. The study demonstrated that the perception of the participants followed the development of the visual pathway as described in empirical neural studies. Salient features presented themselves first and then, over time, details such as space, texture, and finally depth can be learned over many years of development. The eye muscles need to build stamina through guided lessons that provide practice as well as a finished product. It was more important to focus on the variety of qualities of line, shape, and space and strategy building through solution finding and goal setting. Perceptual development indicators of how 8-10-year-old elementary students see and understand images will be heard from their voices. The results indicated that practice exercises helped participants build stamina that directly related to their ability to persist in drawing. -

Organizational Climate in Early Childhood Education

Journal of Education and Training Studies Vol. 6, No. 12; December 2018 ISSN 2324-805X E-ISSN 2324-8068 Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://jets.redfame.com Organizational Climate in Early Childhood Education Mefharet Veziroglu-Celik1, Tulin Guler Yildiz2 1Istanbul Medipol University, Faculty of Education, Early Childhood Education Program, Istanbul, Turkey 2Hacettepe University Faculty of Education, Early Childhood Education Program, Ankara, Turkey Correspondence: Mefharet Veziroglu-Celik, Istanbul Medipol University, Faculty of Education, Early Childhood Education Program, Turkey. Received: September 5, 2018 Accepted: October 15, 2018 Online Published: October 17, 2018 doi:10.11114/jets.v6i12.3698 URL: https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i12.3698 Abstract Organizational climate is a concept that may affect individual behaviors, attitudes and well-being in organizational life as well as explain why some organizations are more productive, effective, innovative and successful than others. The concept has been investigated in many disciplines such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, political science, and management for years and was first considered in education at the end of the 1960s. Since then it has been researched in the field of education in many studies. In this paper, the organizational climate of early childhood centers is examined according to the opinions of early childhood teachers. The Early Childhood Work Environment Scale was used to obtain the data. Participants were a total of 214 teachers who work in public early childhood centers in an urban school district of Turkey. Teachers reported on their opinions of ten components of organizational climate: Collegiality, professional development, director support, clarity, reward system, decision making, goal consensus, task orientation, physical setting, and innovativeness. -

Preschool Teaching Staff 'S Opinions on the Importance Of

c e p s Journal | Vol.5 | No4 | Year 2015 9 Preschool Teaching Staff’s Opinions on the Importance of Preschool Curricular Fields of Activities, Art Genres and Visual Arts Fields Tomaž Zupančič*1, Branka Čagran2, and Matjaž Mulej3 • This article presents preschool teachers’ and assistant teachers’ opinions on the importance of selected fields of educational work in kindergar- tens. The article first highlights the importance of activities expressing artistic creativity within modern curriculums. Then, it presents an em- pirical study that examines the preschool teachers’ and assistant teach- ers’ opinions on the importance of the educational fields, art genres, and visual arts fields. In research hypotheses, we presumed that preschool teachers find individual educational fields, individual art genres, and in- dividual visual arts activities to be of different importance; consequently, education in kindergarten does not achieve the requisite holism. The study is based on the descriptive and causal-non-experimental method. We have determined that the greatest importance is attributed to move- ment and language, followed by nature, society, art and mathematics. Within art genres, the greatest importance is attributed to visual arts and music and the least to audio-visual activities. Within visual arts, drawing and painting are considered to be the most important and sculpting the least. These findings can support future studies and deliberation on the possible effects on practice in terms of requisitely holistically planned preschool education. Keywords: curriculum, preschool education, preschool teachers, requisite holism, visual arts activities 1 *Corresponding Author. Faculty of Education, University of Maribor, Slovenia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Education, University of Maribor, Slovenia 3 Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Maribor, Slovenia 10 preschool teaching staff’s opinions on the importance of preschool curricular .. -

Palpable Pedagogy: Expressive Arts, Leadership, and Change in Social

Antioch University AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses Dissertations & Theses 2009 Palpable Pedagogy: Expressive Arts, Leadership, and Change in Social Justice Teacher Education (An Ethnographic/Auto-Ethnographic Study of the Classroom Culture of an Arts-Based Teacher Education Course) Lucy Elizabeth Barbera Antioch University - PhD Program in Leadership and Change Follow this and additional works at: http://aura.antioch.edu/etds Recommended Citation Barbera, Lucy Elizabeth, "Palpable Pedagogy: Expressive Arts, Leadership, and Change in Social Justice Teacher Education (An Ethnographic/Auto-Ethnographic Study of the Classroom Culture of an Arts-Based Teacher Education Course)" (2009). Dissertations & Theses. 12. http://aura.antioch.edu/etds/12 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student & Alumni Scholarship, including Dissertations & Theses at AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses by an authorized administrator of AURA - Antioch University Repository and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PALPABLE PEDAGOGY: EXPRESSIVE ARTS, LEADERSHIP, AND CHANGE IN SOCIAL JUSTICE TEACHER EDUCATION (AN ETHNOGRAPHIC/AUTO-ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE CLASSROOM CULTURE OF AN ARTS-BASED TEACHER EDUCATION COURSE) LUCY ELIZABETH BARBERA A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Ph.D. in Leadership & Change Program of Antioch University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January, 2009 This is to certify that the dissertation entitled: PALPABLE PEDAGOGY: EXPRESSIVE ARTS, LEADERSHIP, AND CHANGE IN SOCIAL JUSTICE TEACHER EDUCATION (AN ETHNOGRAPHIC/AUTO- ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE CLASSROOM CULTURE OF AN ARTS-BASED TEACHER EDUCATION COURSE) prepared by Lucy Elizabeth Barbera is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Leadership & Change. -

FLEX: a Golden Opportunity for Motivating Students for Foreign Language Study Aleidine Kramer Moeller University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Learning and Teacher Education Education 1990 FLEX: A Golden Opportunity for Motivating Students for Foreign Language Study Aleidine Kramer Moeller University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnfacpub Moeller, Aleidine Kramer, "FLEX: A Golden Opportunity for Motivating Students for Foreign Language Study" (1990). Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education. 168. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnfacpub/168 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 4 FLEX: A Golden Opportunity for Motivating Students for Foreign n age .Study Aleidine J. MoeHerl Central High School; Omaha, Nebraska FLEX is the common acronym used to describe a presequenced Foreign Language EXploratory course ranging in length from six to nine weeks. Such a course is designed to motivate students to pursue foreign language study, to develop their interest in the world and its peoples, and to increase their sensitivity to cultural similarities and differences. There are a variety of FLEX programs in existence (Grittner, 1974). Some are cultural in nature, others emphasize linguistics, and still others are career-based (Strasheim, 1982, p. 60). The FLEX course is usually offered in sixth, seventh, or eighth grade before foreign language study is formally begun and gives the students an introduction to several foreign languages and cultures. -

Reinvesting in Arts Education

President’s Committee on the Arts And the humAnities Reinvesting in Arts Education Winning America’s Future Through Creative Schools reated in 1982 under President Reagan, the President’s CCommittee on the Arts and the Humanities (PCAH) is an advisory committee to the White House on cultural issues. The PCAH works directly with the Administration and the three primary cultural agencies –– National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) –– as well as other federal partners and the private sector, to address policy questions in the arts and humanities, to initiate and support key programs in those disciplines and to recognize excellence in the field. Its core areas of focus are arts and humanities education, cultural exchange, and community revitalization. The First Lady serves as the Honorary Chairman of the Committee, which is composed of both private and public members. Through the efforts of its federal and private members, the PCAH has compiled an impressive legacy over its almost 30-year tenure, conducting major research and policy analysis, and catalyzing important federal cultural programs, both domestic and international. These achievements rely on the PCAH’s unique role in bringing together the White House, federal agencies, civic organizations, corporations, foundations and individuals to strengthen the United States’ national investment in its cultural life. Central to the PCAH’s mission is using the power of the arts and humanities to contribute to the vibrancy of our society, the education of our children, the creativity of our citizens and the strength of our democracy. -

Professional Development of an Educational Psychologist in the System of Psychological and Counseling Service of the University

Propósitos y Representaciones Mar. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(2), e985 ISSN 2307-7999 Special Number: Professional competencies for international university education e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE2.985 RESEARCH NOTES Professional Development Of An Educational Psychologist In The System Of Psychological And Counseling Service Of The University Desarrollo profesional de un psicólogo educativo en el sistema de servicio de psicología y consejería de la universidad Yulia Anatoliyevna Repkina The Institute of Social and Humanitarian Technologies of K.G. Razumovsky Moscow State University of Technologies and Management (the First Cossack University), Moscow, Russia ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1852-3809 Dmitry Vladimirovich Lukashenko Research Institute of the Federal Penitentiary Service of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0045-6062 Violeta Evgenievna Nikolashkina Kutafin Moscow state law University (MSLU), Moscow, Russia ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8365-6088 Liudmila Alekseevna Egorova Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russia ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5159-1512 Marina Georgiyevna Sergeeva Research Institute of the Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia, Moscow, Russia ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8365-6088 Received 09-08-20 Revised 10-10-20 Accepted 20-12-21 On line 02-09-21 *Correspondencia Citar como: Email: [email protected] Anatoliyevna, Y., Vladimirovich, D., Evgenievna, V., Alekseevna, L., & Georgiyevna, M. (2021). Professional Development Of An Educational Psychologist In The System Of Psychological And Counseling Service Of The University. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(SPE2), e986. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE2.986 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2021. -

Benefits of Implementing Visual Arts for Elementary School Students

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 12-2019 Benefits of Implementing Visual Arts for Elementary School Students Desiree Conway California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Art Education Commons Recommended Citation Conway, Desiree, "Benefits of Implementing Visual Arts for Elementary School Students" (2019). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 666. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/666 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: The Benefits of Implementing Visual Arts 1 Benefits of Implementing Visual Arts for Elementary School Students Desiree C. Conway California State University, Monterey Bay The Benefits of Implementing Visual Arts for Elementary School Students 2 Abstract Walking into an elementary classroom you might have observed that visual arts have been consistently disappearing from elementary school classrooms. Visual arts curriculum is especially important in elementary schools because it helps students to fully understand concepts in other areas of their academics. This senior capstone will focus and discuss the many benefits of implementing visual arts into an elementary school classroom. Through the use of literature review and interviews with teachers. The findings reveal that when visual arts are implemented into elementary schools, they do indeed serve students well and have positive effects in all academic areas of elementary school students. -

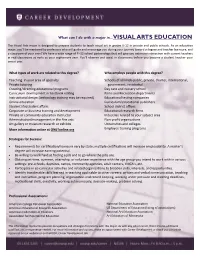

What Can I Do with a Major In...VISUAL ARTS EDUCATION

What can I do with a major in...VISUAL ARTS EDUCATION The Visual Arts major is designed to prepare students to teach visual art in grades K-12 in private and public schools. As an education major, you’ll be mentored by professors who will guide and encourage you during your journey toward a degree and teacher licensure, and a classroom of your own! We have a wide range of P–12 school partnerships that will give you extensive interaction with current teachers in real classrooms as early as your sophomore year. You’ll observe and assist in classrooms before you become a student teacher your senior year. What types of work are related to this degree? Who employs people with this degree? Teaching in your area of specialty Schools of all kinds-public, private, charter, international, Private tutoring government, residential Creating/directing educational programs Day care and nursery school Curriculum development or textbook editing Parks and Recreation departments Instructional design (technology training may be required) Educational testing companies Online education Curriculum/educational publishers Student life/student affairs School district offices Corporate or business training and development Educational research firms Private or community education instructor Industries related to your subject area Administration/management in the fine arts Non-profit organizations Art gallery or museum research or exhibits Universities and colleges More information online at ONETonline.org Employee training programs Strategies for Success: Requirements for certification/licensure vary by state; multiple certifications will increase employability. A master’s degree will increase earning potential. Be willing to work hard at finding a job and to go where the jobs are. -

School Management in the Midst of Educational Technology Advancement

European Journal of Teaching and Education ISSN 2669-0667 School Management in the Midst of Educational Technology Advancement Yosef Gebremeskel1 1 Addis Ababa University; College of Education and Behavioral Studies; Department of Educational Planning and Management. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This qualitative study has been intended to explore school Educational Technology, management practices in the midst of educational technology School Management. advancement. Case study research design has been employed to have an in depth look at practices of a selected school on adopting technology driven school management in a way that addresses the type of technologies introduced and how they have contributed for school management. Accordingly, the school has so far introduced different educational technologies within short period of time. Though positive roles of the introduced educational technologies on improving the existing school management have been recognized by regulatory bodies, further content and context based studies and assessments need to be initiated in a way that enables expansion of the school’s best practices to other private and public schools in the metropolitan. Introduction Technology is a long journey in life experience that creates opportunities for self- reliance. Countries that fail to exercise technology driven approaches can be deprived of their chances to industrialize and grow economically. Youths of a nation should be supported to be engaged in technological education as far as it is an inevitable way to realize success of the entire country. Educational technology is all about improving quality of education through the application of modern technology. Educational technology involves instructional materials, methods and organization of work and relationships of participants in the educational process. -

2002 Cultural Partnership for At-Risk

Cultural Partnership for At-Risk Youth Program 2002 Grantee Abstracts Chinle Unified School District P.O. Box 587 Chinle, AZ 86503 Project Director: Jane Lockart Phone: 928-674-9745 Fax: 928-674-9759 Email: [email protected] S351B02095 Tsilkei doo Ch’ikei Baa Hozhoogo Yigaal Dine Child Development Through Traditional Arts The general framework of the project is the integration of the mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual arts education. These are the characteristics of a human that are stimulated by the teachings from a traditional Navajo perspective. Because Traditional Arts Education from the Navajo perspective is more than just learning dance, music or theater, it is important to know that child development through art is the essence of the whole person. The characteristics that a person develops from conception through old age are what make a person who he or she is and significantly effect the responsibilities and roles that person carries in their many roles throughout life, be it parent, sibling, relative, educator, spiritual person, and leader. Special and unique educational needs exist in this predominantly Navajo student population. It is the responsibility of Chinle Unified School District to build on the teachings of the home, to work to establish a genuine school-home partnership, and to promote parental participation in the formal education of their children. To promote achievement and productive citizenship, the role of Navajo society within the broader western society must be understood. These needs require an approach that reinforces tenets, theories, educational values and philosophies of Navajo culture. Since each student lives in a dual society, relationships between the two societies must be identified and made an integral part of the educational process. -

The Benefits of Engaging in an Arts-Rich Education and the Pedagogical Strategies Used To

The benefits of engaging in an arts-rich education and the pedagogical strategies used to create these benefits in successful part time performing arts schools. Laura Holden Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education The University of Leeds School of Education February, 2018 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. © 2018 The University of Leeds Laura Holden 3 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank my supervisor, Dr Paula Clarke, who has encouraged, challenged, supported, and offered me invaluable advice on all stages of my research project. Her guidance and enthusiasm made my EdD graduate study an enjoyable and achievable experience. I would also like to thank my previous supervisors, Dr Becky Parry and Prof. Ian Abrahams, who helped me to focus my ideas during the earlier stages of the project. I would like to thank the principals and teachers of Stagecoach Theatre Arts schools who allowed me access to their schools and confidential data. Without their assistance this research would have not been possible. Both the principals and teachers have provided insightful ideas and examples of best practice, resulting in a study that I hope is useful to other practitioners that wish to develop the teaching and learning experience in their own areas. Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family who have supported me throughout this process.