Burne-Jones's Reception As a “Great Religious Painter”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

K- 8 Art Curriculum Draft September 2021 Principles Found in the Diocese of Marquette K-8 Art Curriculum

Diocese of Marquette K-8 Art Curriculum September 2021 K- 8 Art Curriculum Draft September 2021 Principles found in the Diocese of Marquette K-8 Art Curriculum Art, the Human Person and God Created "in the image of God," man also expresses the truth of his relationship with God the Creator by the beauty of his artistic works. Indeed, art is a distinctively human form of expression; beyond the search for the necessities of life which is common to all living creatures, art is a freely given superabundance of the human being's inner riches. Arising from talent given by the Creator and from man's own effort, art is a form of practical wisdom, uniting knowledge and skill, to give form to the truth of reality in a language accessible to sight or hearing. To the extent that it is inspired by truth and love of beings, art bears a certain likeness to God's activity in what he has created. Like any other human activity, art is not an absolute end in itself, but is ordered to and ennobled by the ultimate end of man. CCC2501 (CCC: Catechism of the Catholic Church) The Way of Beauty To travel the way of beauty implies educating youth for beauty, helping them develop a critical spirit to discern the various offerings of media culture, and aid them to shape their senses and character in order to grow and lead into true maturity. Beauty itself cannot be reduced to simple pleasure of the senses: this would be to deprive it of its universality, its supreme value, which is transcendent. -

Edward Burne–Jones

EDWARD BURNE–JONES 24 October 2018 – 24 February 2018 LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to the holder CONTENTS Room 1 ................................................................................3 Room 2 ..............................................................................30 Room 3 ..............................................................................69 Room 4 ..............................................................................87 Room 5...................................................................................106 Room 6...................................................................................122 Room 7....................................................................................126 Manton Foyer..........................................................................141 Credits ............................................................................. 143 Events ............................................................................. 145 2 ROOM 1 3 EDWARD BURNE–JONES Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) was one of the key figures in Victorian art, achieving world-wide fame and recognition during his life-time. As the last major figure associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, he led the movement into new symbolist directions where the expression of a mood or idea replaced the earlier focus on providing a realistic description of the natural world. Using myths and legends from the past he created dream-worlds of unparalleled beauty, balancing clarity of observation with dramatically original -

Pre-Raphaelitism Edna Fairchild

PRE-RAPHAELITISM EDNA FAIRCHILD. Bibliography Presented for the Degree of Bachelor of Library Science in the Illinois State Library School in the University of Illinois r PREFACE. It has been the purpose of the compiler in preparing the pre sent work to bring together all the periodical literature on the artistic phase of the Pre-Raphaelite movement in England. The ma terial to be found in histories of art and other books on art subjects, has been but sparingly included, as in every hi story of art will be found a treatise, more or less brief, on the sub ject of Pre-Raphaelitism, and it would be manifestly impossible to procure for examination all of the books to make the b i b l i ography complete. It has seemed advisable, therefore, to in clude in the present bibl iography only the less accessible material. The painters considered in this work are, Rossetti, Millais, and Hunt, the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and Brown and Burne-Jones, the cause and effect, as it were, of the movement. It has seemed that a bibliography which treated fully of the movement as a whole and of the five artists above noted, would be a fairly complete representation of the subject. II A special feature of the work, and one which the compiler trusts will be of assistance to art students and others who are desirous of becoming familiar with the works of the painters of the present century, is the division three (3) under each of the individual painters, i.e., the list of the books and periodi cals examined. -

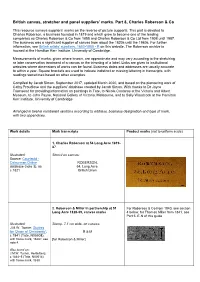

British Canvas, Stretcher and Panel Suppliers' Marks. Part 8, Charles

British canvas, stretcher and panel suppliers’ marks. Part 8, Charles Roberson & Co This resource surveys suppliers’ marks on the reverse of picture supports. This part is devoted to Charles Roberson, a business founded in 1819 and which grew to become one of the leading companies as Charles Roberson & Co from 1855 and Charles Roberson & Co Ltd from 1908 until 1987. The business was a significant supplier of canvas from about the 1820s until the 1980s. For further information, see British artists' suppliers, 1650-1950 - R on this website. The Roberson archive is housed at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge. Measurements of marks, given where known, are approximate and may vary according to the stretching or later conservation treatment of a canvas or the trimming of a label. Links are given to institutional websites where dimensions of works can be found. Business dates and addresses are usually accurate to within a year. Square brackets are used to indicate indistinct or missing lettering in transcripts, with readings sometimes based on other examples. Compiled by Jacob Simon, September 2017, updated March 2020, and based on the pioneering work of Cathy Proudlove and the suppliers’ database created by Jacob Simon. With thanks to Dr Joyce Townsend for providing information on paintings in Tate, to Nicola Costaras at the Victoria and Albert Museum, to John Payne, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, and to Sally Woodcock at the Hamilton Kerr Institute, University of Cambridge. Arranged in twelve numbered sections according to address, business designation and type of mark, with two appendices. Work details Mark transcripts Product marks (not to uniform scale) 1. -

Three Studies for the Golden Stairs A

Edward Coley BURNE-JONES (Birmingham 1833 - London 1898) Three Studies for The Golden Stairs a. Study of the Drapery of the Torso of a Woman Pencil on paper; a page from a sketchbook. A sketch of the head of a child faintly drawn in pencil on the verso. 255 x 140 mm. (10 x 5 1/2 in.) b. Study of the Drapery of the Left Arm of a Woman Pencil on paper; a page from a sketchbook. 255 x 140 mm. (10 x 5 1/2 in.) c. Study of A Woman Holding a Cymbal Pencil on paper; a page from a sketchbook. A nude study of a baby and the head of a young child in brown chalk and pencil on the verso. 255 x 140 mm. (10 x 5 1/2 in.) Taken from one of the artist’s sketchbooks, these three drawings may all be related to one of Edward Burne-Jones’s most significant, and best-known, works, The Golden Stairs, painted between 1876 and 1880. Over two and a half metres in height, the painting is today in the collection of Tate Britain in London. The Golden Stairs was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in London in 1880 to considerable acclaim, with one critic, writing in The Athenaeum, noting that ‘It is an exquisite design, instinct with grace and loveliness…[it] is not only a lovely picture, but beyond all question the painter’s masterpiece.’ An anonymous review of the 1880 Grosvenor Gallery exhibition in the Times praised The Golden Stairs for its ‘beauty and grace, harmony of line, and tender colour, with a suggestion throughout of low- breathed music in the minor key.’ As the same review described the painting; ‘it represents a troop of fair minstrels, clad all in white, coming down a flight of stairs of paly gold, supported by a beautifully- curved arch, from a loggia, on the top of whose cornice doves are perched, while a small space of blue sky is visible through a corner of the square formed by the projecting rafters. -

Aesthetic Movement to Degeneration

• The Aesthetic Movement in England was related to other movements such as Symbolism or Decadence in France and Decadentismo in Italy. • British decadent writers were influenced by Walter Pater who argued that life should be lived intensely with an ideal of beauty. • It was related to the Arts and Crafts movement but this will be traced back to the influence of British decorative design, the Government Schools of Design and Christopher Dresser. • In France, Russia and Belgium Symbolism began with the works of Charles Baudelaire who was influenced by Edgar Allan Poe. • It is related to the Gothic element of Romanticism and artists include Fernand Khnopff, Gustave Moreau, Gustav Klimt, Odilon Redon, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Henri Fantin-Latour, and Edvard Munch. These artists used mythology and dream imagery based on obscure, personal symbolism. It influenced Art Nouveau and Les Nabis (such as Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard and Maurice Denis). • In Italy, Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938) promoted irrationality against scientific rationalism. 1 Simeon Solomon (1840-1905), Walter Pater, 1872, pencil on paper, Peter Nahum Ltd, Leicester Galleries Walter Pater (1839-1894) • Essayist, literary and art critic and fiction writer. His father was a physician but died when he was young and he was tutored by his headmaster. His mother died when he was 14 and he gained a scholarship to Queen’s College, Oxford in 1858. • He read Flaubert, Gautier, Baudelaire and Swinburne and learnt German and read Hegel. He did not pursue ordination despite an early interest. He stayed in Oxford and was offered a job at Brasenose teaching modern German philosophy. -

Truth and Beauty: the Pre-Raphaelite Movement

Art Appreciation Lecture Series 2014 Realism to Surrealism: European Art and Culture 1848-1936 Truth and beauty: the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Assoc. Prof. Alison Inglis, University of Melbourne 29 / 30 January 2014 Lecture summary: This lecture will investigate the work of the group of English artists known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. It will explore the context in which the Brotherhood was formed in 1848 and identify the features of their art that were regarded as controversial. The careers for the three key artists associated with the Brotherhood, namely, John Millais, William Holman-Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, will be examined as well as the work of some of their followers, in particular, Edward Burne-Jones. Special attention will be given, whenever possible, to works by the Pre-Raphaelites in Australian collections. Finally, the transformation of the Pre-Raphaelites from a semi-secret ‘Brotherhood’ into a more general movement within later nineteenth-century Britain, namely ‘Pre- Raphaelitism’ will be considered. The extent to which the artistic movement can be regarded as ‘avant-garde’ (in style, in subject matter, in the lifestyle of its practitioners) will also be addressed throughout the presentation. Slide list: 1. Ford Madox Brown, The last of England, 1852-55, oil on canvas, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, purchased 1891. 2. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Thomas Woolner, 1852, pencil on wove paper, National Portrait Gallery, London, purchased 1953. 3. Ford Madox Brown, Compositional study for ‘The last of England’, 1852-55, pencil and brown ink on paper, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, purchased and presented by subscribers 1906. -

Sir Edward Burne-Jones

’ Bell M i nia ure Series Of Paint e rs s t . Ed ed b G . C . O L . D . it y WILLIAMS N, itt VE AZ EZ. WI LLI AMSON L t . D L U G C t . Q By , i - U RN ON S . M LC LM ELL. SI R E. B E J E By A O B L . WI L S t F RA ANGE I CO . G C L I AM N L t. D . By O , i WA A AND HI S P PI S EDG M TTE U U L . By CU BE STALEY, B . A. F . W R . G A S A . C . ATEMAN TT , By T B . GEORGE ROMNEY . R WLEY CLEEVE By O . O HERS TO F LL W T O O . LONDON : G ORGE B LL SO E E NS, YORK S COVENT G D TREET, AR EN. Holl er o to F . y plz j ’ THE P R I R E TA LE O SS S . ’ Bell s M iniat ure Series Of Paint ers S I R EDWA RD B U R N E - J O N E S BY M ALCOLM BELL LONDON GEORGE BE LL SONS 1 90 1 FAM I L OJ T CHlSWlCK PRESS : CHA RLES WHI T I NG HA M A N D CO . TOOK COURT C H NCE RY LA N E LO N DO N . S , A , TABLE OF CONTE NTS C HAP. HI S B I . IRTH AND EDUCATION K II . HI S PICTORIAL WOR V WORR III . -

The Burne-Jones Pianos and the Victorian Female Gender Performance

PERFORMING UPON HER PAINTED PIANO: THE BURNE-JONES PIANOS AND THE VICTORIAN FEMALE GENDER PERFORMANCE By AMELIA KATE ANDERSON A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Amelia Kate Anderson Title: Performing Upon Her Painted Piano: The Burne-Jones Pianos and The Victorian Female Gender Performance This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Dr. Nina Amstutz Chairperson Dr. Joyce Cheng Member Dr. Marian Smith Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Amelia Kate Anderson iii THESIS ABSTRACT Amelia Kate Anderson Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture June 2017 Title: Performing Upon Her Painted Piano: The Burne-Jones Pianos and The Victorian Female Gender Performance This thesis centers around three pianos designed and/or decorated by the Victorian artist Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones: The Priestley Piano, The Graham Piano, and the Ionides Piano. I read and interpret the Burne-Jones pianos not only as eXamples of the artist’s exploration of the boundaries of visual art and music, but also as reflections of the Victorian era female gender performance. Their physical forms and decorations, both designed and eXecuted by Burne-Jones, enhance the piano as an instrument and accentuate their respective female performers. -

Christian Fiction List

1/12/20181/12/2018 Christian Inspirational Fiction -January 2019- Lansing Public Library Compiled by Lansing Public Library / Reference Dept. Christian / Inspirational Fiction 1 hristian fiction is a popular collection at Lansing Public Library. This C genre covers a wide range from the gentle-reads of Janette Oke to the apocalyptic tales of good and evil of Frank Peretti. While some have a distinct Christian message others are just good stories of people trying to live out their faith or work through their doubts. They don’t include profanity, sex or graphic violence. We try to keep up with series as they are published, but if you don’t see what you’re looking for, we will be glad to order it for you. Enjoy! -A new edition of this booklet is published each January, May and September. An updated insert will be available each of the other months.- -indicates new author added since last update -new titles since last update will also be highlighted in color -this shading indicates that title is no longer owned by Lansing Library Acker, Rick 1. Dead man’s rule, 2005 F/ACK 2. Blood brothers, 2008 F/ACK Adams, Stacy Hawkins 1. Speak to my heart, 2004 F/ADA 2. Watercolored pearls, 2007 F/ADA Jubilant soul series 1. The someday list, 2009 F/ADA 2. Worth a thousand words, 2009 F/ADA 3. Dreams that won’t let go, 2010 F/ADA Winds of change series 1. Coming home, 2012 F/ADA 2. Lead me home, 2013 F/ADA 3. Finding home Compiled by Lansing Public Library / Reference Dept. -

Cinq Remarques Sur Burne Jones / Five Notes on Burne-Jones

Document generated on 09/27/2021 4:21 a.m. Vie des arts Cinq remarques sur Burne Jones Five Notes on Burne-Jones Jean-Loup Bourget Volume 20, Number 79, Summer 1975 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/55100ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La Société La Vie des Arts ISSN 0042-5435 (print) 1923-3183 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Bourget, J.-L. (1975). Cinq remarques sur Burne Jones / Five Notes on Burne-Jones. Vie des arts, 20(79), 46–75. Tous droits réservés © La Société La Vie des Arts, 1975 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Cinq remarques sur Burne Jones Jean-Loup Bourget Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) est, avec Barbu c. Imberbe William Morris, le principal représentant de la Vêtement c. Nudité (bras, jambes,...) seconde génération préraphaélite: celle qui, Armure c. Robe tournant le dos au naturalisme moralisant d'Holman Hunt, s'engage, à la suite de Rossetti, Ajoutons, en ce qui concerne la composition dans la voie du symbolisme décoratif. Consi du tableau, déré à la fin du 19e siècle comme un des plus Profil c. Face grands artistes contemporains, Burne-Jones subit ensuite une éclipse. -

Theatre Magick: Aleister Crowley and the Rites of Eleusis

THEATRE MAGICK: ALEISTER CROWLEY AND THE RITES OF ELEUSIS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Tracy W. Tupman, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Joy H. Reilly, Advisor Dr. Alan Woods ________________________________ Advisor Dr. Lesley Ferris Theatre Graduate Program ABSTRACT In October and November of 1910 seven one-act plays were produced at Caxton Hall, Westminster, London, under the collective title The Rites of Eleusis. These public productions were as much an experiment in audience and performer psychology as they were an exotic entertainment. Written, produced and directed by leading cast member, Aleister Crowley, The Rites of Eleusis attempted to present a contemporary interpretation of an ancient myth in order to reignite the role and importance of mysticism in modern society. Through exposing the audience to a variety of sensory stimuli such as incense, rhythmic music, dance, and poetry, it attempted to create within the audience itself an altered state of consciousness which would make them co-celebrants within the performance/ritual. As Crowley stated in the original broadsheet advertisements for the productions, the Rites were intended “to illustrate the magical methods followed by a mystical society which seeks for illumination by ecstasy.” But Crowley intended much more: he hoped the audience would not merely view an “illustration,” but experience an