INTERPRETING the PARABLES.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of Jesus: from Birth to Death to Life” – Week One Overview

St. John’s Lutheran Church, Adult Education Series, Spring 2019 “The Story of Jesus: from Birth to Death to Life” – Week One Overview A. The Four Gospels – Greek, euangelion, “good news,” Old English, god-spel “Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book. But these are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.” (John 20:30-31) 1. Mark a. author likely John Mark, cousin of Barnabas (Col 4:10), companion of Peter (Acts 12:12) and Paul (Acts 12:12, 15:37-38) b. written ca 50-65 AD, perhaps after death of Peter c. likely written to Gentile Christians in Rome d. focus on Jesus as the Son of God 2. Matthew a. author likely Matthew (Levi), one of the Twelve Apostles b. written ca 60-70 AD c. likely written to Jewish Christians d. focus on Jesus as the Messiah 3. Luke a. author likely Luke, physician, companion of Paul (Col 4:14), author of Acts, gives an orderly account (1:1-4) b. written ca 60-70 AD c. addressed to Theophilus (Greek, “lover of God”), Gentile Christians d. focus on Jesus as the Savior of all people 4. John a. author possibly John, one of the Twelve Apostles – identifies himself as the “beloved disciple” (John 21:20) b. written ca 80-100 AD c. addressed to Jewish and Gentile Christians d. focus on Jesus as God incarnate 1 St. -

GRADES 4/5 Supplemental Scripture Parables in the Gospel of Matthew

Catholic Arts & Academic Competition Catholic Heroes GRADES 4/5 Supplemental Scripture Parables in the Gospel of Matthew Lamp under a bushel 5:14-15 14 “You are the light of the world. A city built on a hill cannot be hid. 15 No one after lighting a lamp puts it under the bushel basket, but on the lampstand, and it gives light to all in the house. Wise and foolish builders 7:24-27 24 “Everyone then who hears these words of mine and acts on them will be like a wise man who built his house on rock. 25 The rain fell, the floods came, and the winds blew and beat on that house, but it did not fall, because it had been founded on rock. 26 And everyone who hears these words of mine and does not act on them will be like a foolish man who built his house on sand. 27 The rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell—and great was its fall!” Sower and four types of soil 13:3-8, 18-23 3 And he told them many things in parables, saying: “Listen! A sower went out to sow. 4 And as he sowed, some seeds fell on the path, and the birds came and ate them up. 5 Other seeds fell on rocky ground, where they did not have much soil, and they sprang up quickly, since they had no depth of soil. 6 But when the sun rose, they were scorched; and since they had no root, they withered away. -

1 1 Thessalonians 5: 1-11, Matthew 25: 14-30 Olivet

1 Thessalonians 5: 1-11, Matthew 25: 14-30 Olivet Church, Charlottesville --- November 19, 2017 We Belong to the Day We are tempted to treat Jesus’ parables as allegories, with the characters and events in the stories representing God, historical figures, and events. But the harshness of the master in today’s parable discourages us from making a correlation between him and God or Jesus, and reminds us that these stories are not allegories. And there are those who use Jesus’ teachings about the end-time, when he returns to judge the world and usher in the fullness of God’s kingdom, to instill fear in people that they might return to God and God’s way. But the fact that the servant who was judged harshly, and thrown into outer darkness, had acted out of fear should discourage us from using the threat of judgement to instill faith and discipleship. The Parable of the Talents is part of Jesus' discourse with his disciples about enduring through difficult times while living in anticipation of his return. It recalls the parable of the faithful and wise slave in chapter 24, who, although the master is delayed, continues to do the work of the master until the master returns to find him doing the tasks that have been appointed to him in the master's absence. A remarkable element of the Parable of the Talents is the amount of wealth that is entrusted to each servant. A talent, a certain weight of precious metal, was equal to about 6,000 denarii. Since one denarius was a common laborer's daily wage, a talent would be roughly equivalent to 20 years of wages. -

Table of Contents Explanation of Lectio Divina

Lectio Divina for the Retreat Feb 2021 The Gospel of Mark – In the Year of Mark All the following passages are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition of the Bible (NRSVCE). This is the version that is used in the Canadian Lectionary (the readings we hear at mass on the weekdays and on Sunday.). The reason I chose this version is so that we would be familiar with this version and when we listen to the Gospel being proclaimed, we can have a connection to its proclamation. We will not have time to walk through the Gospel of Mark in its entirety, but in a chronological walk through, life some major themes. I have included the paragraph titles following the readings, so that we can have a bird’s eye view of the development of the Gospel. St. Mark is particular in the order he presents the events of Jesus’ life. He does this to emphasize that Jesus’ Journey from the beginning of His ministry is always moving toward Jerusalem to accomplish what He was sent to do, save humanity by becoming the sacrificial Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world through His passion, death and resurrection. Try to read the passages before attending the live stream ‘Lectio Divina’ and allow the Word of God to speak to your soul. If at all possible, avoid printing the pages to save on paper. You can use a journal to write down words or phrases that remain with you and the that Lord is speaking to you. -

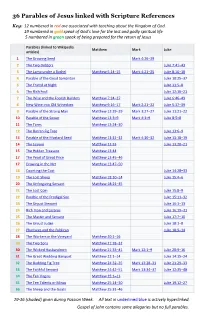

36 Parables of Jesus Linked with Scripture References

36 Parables of Jesus linked with Scripture References Key: 12 numbered in red are associated with teaching about the Kingdom of God 19 numbered in gold speak of God’s love for the lost and godly spiritual life 5 numbered in green speak of being prepared for the return of Jesus Parables (linked to Wikipedia Matthew Mark Luke articles) 1 The Growing Seed Mark 4:26–29 2 The Two Debtors Luke 7:41–43 3 The Lamp under a Bushel Matthew 5:14–15 Mark 4:21–25 Luke 8:16–18 4 Parable of the Good Samaritan Luke 10:25–37 5 The Friend at Night Luke 11:5–8 6 The Rich Fool Luke 12:16–21 7 The Wise and the Foolish Builders Matthew 7:24–27 Luke 6:46–49 8 New Wine into Old Wineskins Matthew 9:16–17 Mark 2:21–22 Luke 5:37–39 9 Parable of the Strong Man Matthew 12:29–29 Mark 3:27–27 Luke 11:21–22 10 Parable of the Sower Matthew 13:3–9 Mark 4:3–9 Luke 8:5–8 11 The Tares Matthew 13:24–30 12 The Barren Fig Tree Luke 13:6–9 13 Parable of the Mustard Seed Matthew 13:31–32 Mark 4:30–32 Luke 13:18–19 14 The Leaven Matthew 13:33 Luke 13:20 21 – 15 The Hidden Treasure Matthew 13:44 17 The Pearl of Great Price Matthew 13:45–46 17 Drawing in the Net Matthew 13:47–50 18 Counting the Cost Luke 14:28–33 19 The Lost Sheep Matthew 18:10–14 Luke 15:4–6 20 The Unforgiving Servant Matthew 18:21–35 21 The Lost Coin Luke 15:8–9 22 Parable of the Prodigal Son Luke 15:11–32 23 The Unjust Steward Luke 16:1–13 24 Rich man and Lazarus Luke 16:19–31 25 The Master and Servant Luke 17:7–10 26 The Unjust Judge Luke 18:1–8 27 Pharisees and the Publican Luke 18:9–14 28 The Workers in the Vineyard Matthew 20:1–16 29 The Two Sons Matthew 21:28–32 30 The Wicked Husbandmen Matthew 21:33–41 Mark 12:1–9 Luke 20:9–16 31 The Great Wedding Banquet Matthew 22:1–14 Luke 14:15–24 32 The Budding Fig Tree Matthew 24:32–35 Mark 13:28–31 Luke 21:29–33 33 The Faithful Servant Matthew 24:42–51 Mark 13:34–37 Luke 12:35–48 34 The Ten Virgins Matthew 25:1–13 35 The Ten Talents or Minas Matthew 25:14–30 Luke 19:12–27 36 The Sheep and the Goats Matthew 25:31 46 – 29-36 (shaded) given during Passion Week. -

B I G M E a N I

LITTLE STORIES with B I G M E A N I N G Parables in Poetic Form by Shirley May Davis Copyright c January 2003 by Shirley May Davis TABLE of CONTENTS Index ..................................................................... 3 Lamp Light .......................................................... 5 The Difference ................................................... 6 New Versus Old ................................................. 7 Heart Condition .................................................. 8 Small Beginnings .................................................9 Wheat or Weeds .................................................10 Heaven Like Leaven ..........................................11 Treasure Without Measure ..............................11 Pearl Seeker .........................................................12 Fish - In or Out ................................................... 12 Lost and Found ................................................... 13 Importance of Forgiveness .............................14 Penny Paycheque ...............................................15 To Go or Not To Go ..........................................16 To Feast or Not To Feast .................................17 Vengeance in the Vineyard .............................18 Little or Much ................................................... 19 Ready or Not, Here I Come..............................20 Wise or Foolish .................................................. 21 Neighbourliness .................................................. 22 Unwise Decision -

Echoes from the Sermon on the Mount

19 Echoes from the Sermon on the Mount John W. Welch The memorable and impressive words of the Sermon on the Mount (see Matthew 5–7; 3 Nephi 12–14) reverberate throughout corridors and chambers of the gospel of Jesus Christ. In many ways, the Sermon stands at the heart of the teachings of Christ, and if people will build upon these words, by hearing and doing them, they will be built “upon the rock” (Greek epi te¯n petran, Matthew 7:24) that will withstand the winds and floods of destruction. Jesus himself and his early disciples set an important example of building upon these words as they went forth to teach and administer. In the following pages, I draw attention to the fact that wording from the Sermon on the Mount is quoted or paraphrased in subsequent sections of the Book of Mormon and the New Testament more often than people typically realize. This pattern of drawing and building on the founda- tional words of the Sermon was established by Jesus as he gave the Sermon in 3 Nephi 12–14 and then quoted from it significantly in 3 Nephi 15–28. This same practice is evident in the Synoptic Gospels. In particular John W. Welch is the Robert K. Thomas Professor of Law at the J. Reuben Clark Law School at Brigham Young University and editor in chief of BYU Studies. 313 314 John W. Welch contexts and for important reasons, Jesus quoted or paraphrased from the sermon throughout his ministry, as reported by Matthew, Mark, and Luke. -

26 February 2017 COMMUNITY of CHRIST LESSONS

COMMUNITY OF CHRIST LESSONS ADULT 8 JANUARY 2017–26 February 2017 COMMUNITY OF CHRIST LESSONS Lifelong Disciple Formation in Community of Christ is the shaping of persons in the likeness of Christ at all stages of life. It begins with our response to the grace of God in loving community and continues as we help others learn, grow, and serve in the mission of Jesus Christ. Ultimately, discipleship is expressed as one lives the Mission Initiatives of the church through service, generosity, witness, and invitation. We invite you to use these lessons for your class, group, or congregation. Lectionary-based: The weekly lessons connect the Revised Common Lectionary for worship with Community of Christ identity, mission, message, and beliefs. Quick, easy: The lessons are designed for approximately 45-minute class sessions with two to three pages of ideas, discussion starters, and activities. Additional preparation help may be found in Sermon and Class Helps, Year A: New Testament (with focus on the gospel according to Matthew). Lessons are available for three age groups. Recognizing each age group represents multiple stages of development, the instructor is encouraged to adapt lessons to best meet the needs of the class or group. When possible, optional activities are provided to help adapt lessons for diverse settings. Children (multiage, 6–11): Help children engage in the Bible and introduce mission and beliefs with stories, crafts, and activities. Youth (ages 12–18): Engage youth in scripture study and provocative questions about identity, mission, message, and beliefs. Adult (ages 19 and older): Deepen faith and understanding with reflective questions, theological understanding, and discussion ideas. -

A WINTER BIBLE STUDY on House Will Not Be Able to Stand

kingdom cannot stand. And if a house is divided against itself, that A WINTER BIBLE STUDY ON house will not be able to stand. And if Satan has risen up against himself and is divided, he cannot stand, but his end has come. But no one can enter a strong man’s house and plunder his property Tuesday March 16, 2021: Session 4 - Readings without first tying up the strong man; then indeed the house can be Galilee: “The Purpose of Parables” Mark 3:7-4:34 plundered. A Multitude at the Seaside “Truly I tell you, people will be forgiven for their sins and whatever Jesus departed with his disciples to the sea, and a great multitude blasphemies they utter; but whoever blasphemes against the Holy from Galilee followed him; hearing all that he was doing, they came Spirit can never have forgiveness, but is guilty of an eternal sin”— to him in great numbers from Judea, Jerusalem, Idumea, beyond the for they had said, “He has an unclean spirit.” Jordan, and the region around Tyre and Sidon. He told his disciples What Does It Mean: The “Unforgivable” sin. to have a boat ready for him because of the crowd, so that they would In Mark 3:22–30 we find one of the more difficult teachings from not crush him; for he had cured many, so that all who had diseases Jesus—the so-called unforgivable sin. Here, the scribes confront pressed upon him to touch him. Whenever the unclean spirits saw Jesus about his teachings. They’ve begun to spread the rumor that him, they fell down before him and shouted, “You are the Son of he is possessed by a demon named “Beelzebul,” which was a high- God!” But he sternly ordered them not to make him known. -

Jesus Teaches in Parables, Controls Nature, and Raises the Dead

Handout 1: Mark Lesson 4 1. Parable of the Cloth and Wineskins (Mk 2:21-22) 2. Parable of the Strong Man (Mk 3:23-27) 3. Parable of the Sower (Mk 4:3-8) 4. Parable of the Lamp (Mk 4:21-25) 5. Parable of the Seed that Grows Itself (Mk 4:26-29; only in Mark) 6. Parable of the Mustard Seed (Mk 4:30-32) 7. Parable of Clean and Unclean (Mk 7:14-23) 8. Parable of Salt (Mk 9:49-50) 9. Parable of the Tenants (Mk 12:1-9) 10. Parable of the Fig Tree (Mk 13:28-31) Symbolism in the Parable of the Seed and the Sower The seed The word of God The sower Jesus Different soil conditions Four kinds of responses by people who hear the word Symbolism in the four kinds of soil where the seed is sown 1. Seed sown on the path This person hears the word of the kingdom without making any effort to understand and embrace the truth. Since he has failed to understand, Satan is able to separate him from the truth and from his place in the Kingdom. 2. Seed sown on rocky ground This person receives the word of God with joy, but he has not applied the word to his life; he has no internal stability (“roots”). In a time of hardship, he abandons his faith in God. 3. Seed sown among the thorns This person hears the word but does not love God above all else; the secular world pulls him away from faith and he bears no good fruit/works. -

1 the Gospel According to Saint Mark November 8, 2020 Mark 4:1-33

The Gospel according to Saint Mark November 8, 2020 Mark 4:1-33 4Again he began to teach beside the sea. Such a very large crowd gathered around him that he got into a boat on the sea and sat there, while the whole crowd was beside the sea on the land. 2 He began to teach them many things in parables, and in his teaching he said to them: 3 “Listen! A sower went out to sow. 4 And as he sowed, some seed fell on the path, and the birds came and ate it up. 5 Other seed fell on rocky ground, where it did not have much soil, and it sprang up quickly, since it had no depth of soil. 6 And when the sun rose, it was scorched; and since it had no root, it withered away. 7 Other seed fell among thorns, and the thorns grew up and choked it, and it yielded no grain. 8 Other seed fell into good soil and brought forth grain, growing up and increasing and yielding thirty and sixty and a hundredfold.” 9 And he said, “Let anyone with ears to hear listen!” The Purpose of the Parables 10 When he was alone, those who were around him along with the twelve asked him about the 11 parables. And he said to them, “To you has been given the secret[a] of the kingdom of God, but for those outside, everything comes in parables; 12 in order that ‘they may indeed look, but not perceive, and may indeed listen, but not understand; so that they may not turn again and be forgiven.’” 13 And he said to them, “Do you not understand this parable? Then how will you understand all the parables? 14 The sower sows the word. -

LAITY SUNDAY 2015 Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

LAITY SUNDAY 2015 Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) “This, then, is how you should pray: “„Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name, your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us today our daily bread. And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one. Jesus said to them, “Very truly I tell you, it is not Moses who has given you the bread from heaven, but it is my Father who gives you the true bread from heaven. “GiveGive usus thisthis dayday ourour dailydaily Bread…”Bread…” SolidSolid FoodFood For the bread of God is the bread that comes down from heaven and gives life to the world.” “Sir,” they said, “always give us this bread.” Then Jesus declared, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never go hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty. BitesBites fromfrom thethe BibleBible When it comes to the Bible, there is so much to marvel and to learn. There are miracles of many kinds that are per- said, (and he then goes on to quote the prophecy written by formed by Jesus and some by the apostles (when they be- Isaiah hundreds of years before) “These people will listen and lieved). We have heard stories; some we know well and listen, but never understand. They will look and look, but nev- others we only remember them as we were told as children. er see.