2007 Report of Gifts (140 Pages) South Caroliniana Library--University of South Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

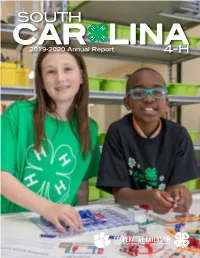

2019-2020 Annual Report 4-H

SOUTH CAR LINA 2019-2020 Annual Report 4-H 4-H Annual Report 2020 • 1 Here’s whats Inside 4-H Inspires Shooting for Success 3 Youth to Do Volunteers Honored 4 4-H is a community of young people across America who are learning leadership, citizenship, and life skills. In 4-H, we believe 4-H @ Home Wins Award 5 in the power of young people. We see that every child has valuable Pinckney Leadership 6 strengths and real influence to improve the world around us. 4-H welcomes youth of all Project, Programs Go On 8 backgrounds and beliefs, empowering them 4-H Legislative Day 10 with the skills and confidence to lead for a lifetime. Garden Classrooms 11 With more than 104,000 4-H’ers (ages Mars Madness 12 5-18) and thousands of adult volunteers, South Carolina 4-H focuses on providing Deep Rooted Alumni 14 positive youth development experiences to Healthy Lifestyles 16 young people by enhancing and increasing their knowledge in civic engagement, Presidential Tray Recipients 20 leadership, communication skills, STEM, 2020 Scholarship Winners 22 natural resources, healthy lifestyles, horses, livestock and agriculture. Pam Ardern The 4-H community club is the foundation Dr. Pam Ardern of South Carolina 4-H, where youth learn life skills such as State 4-H Program Team Director civic engagement, community awareness, global awareness, 864-650-0295 communication, and leadership. Through community club Dr. Ashley Burns involvement, 4-H members are becoming self-directing, productive, Assistant 4-H Program Team Director and contributing members of our society while learning in safe and 404-580-7984 inclusive environments. -

2015 Session Ļ

MEMBERS AND OFFICERS OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Ļ 2015 SESSION ļ STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA Biographies and Pictures Addresses and Telephone Numbers District Information District Maps (Excerpt from 2015 Legislative Manual) Corrected to March 24, 2015 EDITED BY CHARLES F. REID, CLERK HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA MEMBERS AND OFFICERS OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Ļ 2015 SESSION ļ STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA Biographies and Pictures Addresses and Telephone Numbers District Information District Maps (Excerpt from 2015 Legislative Manual) Corrected to March 24, 2015 EDITED BY CHARLES F. REID, CLERK HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA THE SENATE Officers of the Senate 1 THE SENATE The Senate is composed of 46 Senators elected on November 6, 2012 for terms of four years (Const. Art. III, Sec. 6). Pursuant to Sec. 2-1-65 of the 1976 Code, as last amended by Act 49 of 1995, each Senator is elected from one of forty-six numbered single-member senatorial districts. Candidates for the office of Senator must be legal residents of the district from which they seek election. Each senatorial district contains a popu- lation of approximately one/forty-sixth of the total popula- tion of the State based on the 2010 Federal Census. First year legislative service stated means the year the Mem- ber attended his first session. Abbreviations: [D] after name indicates Democrat, [R] after name indicates Republican; b. “born”; g. “graduated”; m. “married”; s. “son of”; d. “daughter of.” OFFICERS President, Ex officio, Lieutenant Governor McMASTER, Henry D. [R]— (2015–19)—Atty.; b. -

Higher Education in South Carolina

Higher Education in South Carolina A Briefing on the State’s Higher Education System Prepared by SC Commission on Higher Education March 2010 1333 Main Street • Suite 200 • Columbia, SC 29201 • Phone: (803) 737-2260 • Fax: (803) 737-2297 • Web: www.che.sc.gov South Carolina is home to a robust higher education system including 33 public institutions including 3 research universities, 10 comprehensive four-year universities, 4 two-year regional campuses of the University of South Carolina and 16 technical colleges. The State is also home to a number of independent and private colleges including: 23 independent senior colleges and universities, 2 independent two-year colleges, a private senior college, a private for- profit law school, and a private for-profit junior college. Together, these institutions with their varied missions and character are serving over 240,000 students. Other options for those seeking higher education opportunities within the State include at least 23 out- of-state degree granting institutions that are licensed by the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education to operate in the state. Apart from the public institutions, there are three state agencies tasked with specific responsibilities and duties relating to higher education in South Carolina. The South Carolina Commission on Higher Education is the agency in state government specializing in post-secondary education and responsible for quality, efficiency, accountability, accessibility, and studies and plans for higher education and recommending courses of action to ensure a coordinated system of higher education in the state. The State Board for Technical and Comprehensive Education has key responsibilities in regard to ensuring that the system of technical colleges is responsive to needs for industry and workforce development. -

Winthrop University

WINTHROP UNIVERSITY Independent Auditors' Report Financial Statements and Schedules For the Year Ended June 30, 2007 State of South Carolina Office of the State Auditor 1401 MAIN STREET, SUITE 1200 COLUMBIA, S.C. 29201 RICHARD H. GILBERT, JR., CPA (803) 253-4160 DEPUTY STATE AUDITOR FAX (803) 343-0723 October 3, 2007 The Honorable Mark Sanford, Governor and Members of the Board of Trustees Winthrop University Rock Hill, South Carolina This report on the audit of the basic financial statements of Winthrop University and the accompanying schedule of expenditures of federal awards as required by U.S. Office of Management and Budget Circular A-133, Audits of States, Local Governments, and Non-Profit Organizations, for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2007, was issued by Cline Brandt Kochenower & Co., P.A., Certified Public Accountants, under contract with the South Carolina Office of the State Auditor. If you have any questions regarding this report, please let us know. Respectfully submitted, Richard H. Gilbert, Jr., CPA Deputy State Auditor RHGjr/trb WINTHROP UNIVERSITY Table of Contents Page State Auditor’s Transmittal Letter FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditors' Report 1-2 Management=s Discussion and Analysis 3-7 Statement of Net Assets 8 Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Assets 9 Statement of Cash Flows 10-11 Component Unit - The Winthrop University Foundation Statement of Financial Position 12 Component Unit - The Winthrop University Foundation Statement of Activities 13 Component Unit - Winthrop University Real Estate -

Clemson Businesses React to Governor's Decision

| PAGE LABEL EVEN | ‘NOT MUCH T Vol. 117HE No. 42 JOURNALTuesday, March 2, 2021 $100 TO SAY’ T J Swinney talks AT A DISTANCE: Glam back at annual Golden Globes, albeit virtually. B1 about Kendrick’s PLEA FOR HELP: Countries urge drug companies to share vaccine know-how. D1 departure. C1 CLEMSON Clemson businesses react to governor’s decision As of Monday, restaurants “Lifting the 11 p.m. alcohol an effort on the part of the busi- and bars are now able to sell curfew will have a strong impact ness owners, or most anyway, to McMaster announced end of some alcohol after 11 p.m. again, and on downtown, but, of course, abide by the guidelines.” event organizers no longer have they will still be held to the city’s Cohen also said the realiza- COVID-19 safety measures Friday to secure permits for groups of mask ordinance,” Clemson Area tion was made recently that more than 250 people, according Chamber of Commerce pres- the restrictions in Clemson to McMaster’s announcement. ident Susan Cohen said. “We, were simply driving students to BY GREG OLIVER terminate COVID-19 safety mea- State health officials said peo- the chamber and the hospital- travel to nearby schools or other THE JOURNAL sures over the sale of alcohol ple should still practice social ity industry maintain that the cities or states. and mass gatherings was greet- distancing and wear face cov- students and the community as a Cohen said safety precautions CLEMSON — Gov. Henry ed with a “wait and see” attitude erings, along with other safety whole are safer with the later bar McMaster’s decision Friday to from Clemson businesses. -

Georgia State 41, Shorter 7 30,237 FANS at GEORGIA DOME

2017 FOOTBALL SCHEDULE GEORGIA STATE PANTHERS TENNESSEE STATE (ESPN3) TROY (Homecoming)* Aug. 31 | 7 p.m. | Georgia State Stadium Oct. 21 | TBA | Georgia State Stadium at PENN STATE (BTN) SOUTH ALABAMA (ESPNU)* Sept. 16 | 7:30 p.m. | State College, Pa. Oct. 26 | 7:30 p.m. | Georgia State Stadium at CHARLOTTE at GEORGIA SOUTHERN* Sept. 23 | TBA | Charlotte, N.C. Nov. 4 | TBA | Statesboro, Ga. MEMPHIS at TEXAS STATE* Sept. 30 | TBA | Georgia State Stadium Nov. 11 | TBA | San Marcos, Texas at COASTAL CAROLINA* APPALACHIAN STATE* Oct. 7 | TBA | Conway, S.C. Nov. 25 | TBA | Georgia State Stadium at UL MONROE* IDAHO* Oct. 14 | TBA | Monroe, La. Dec. 2 | TBA | Georgia State Stadium Subject to change | All times Eastern * Sun Belt Conference game 2017 GEORGIA STATE FOOTBALL TABLEOFCONTENTS 2017 Schedule ..................................... 1 Assistant Coaches.............................31 GENERAL INFORMATION Football Staff Directory .................... 3 Football Support Staff.....................40 Full Name Georgia State University Georgia State Stadium ...................... 4 Player Profiles ....................................42 GSU Practice Complex ...................... 7 2016 Statistics....................................78 Location Atlanta, Ga. GSU Football Timeline ...................... 8 2016 Season Review ........................86 Founded 1913 Georgia State University ................10 School Records ..................................94 Campus Housing ..............................12 Single-Game Highs ..........................98 -

Baseball Media Guide 2017

Wofford College Digital Commons @ Wofford Media Guides Athletics 2-1-2017 Baseball Media Guide 2017 Wofford College. Department of Athletics Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/mediaguides Recommended Citation Wofford College. Department of Athletics, "Baseball Media Guide 2017" (2017). Media Guides. 64. https://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/mediaguides/64 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at Digital Commons @ Wofford. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Guides by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Wofford. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2017 MEDIA GUIDE WOFFORDTERRIERS.COM SOCON CHAMPIONS: ’07 @WOFFORDBASEBALL NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCE: ’07 @WOFFORDTERRIERS © 2017 adidas AG 2017 BASEBALL WOFFORD MEDIA GUIDE 2017 SCHEDULE TABLE OF CONTENTS Date Opponent Time April 4 at Navy 3:00 pm Wofford Quick Facts/Staff ...............................................2 Feb. 17 at Florida A&M 4:00 pm April 7 VMI * 6:00 pm Media Information .........................................................3 Feb. 18 at Florida A&M 1:00 pm April 8 VMI * 3:00 pm Wofford College ..........................................................4-9 Feb. 19 at Florida A&M 1:00 pm Russell C. King Field ................................................10-11 April 9 VMI * 1:00 pm Strength and Conditioning ...........................................12 Feb. 22 at Presbyterian 2:00 pm April 11 at UNC Asheville 6:00 pm Feb. 24 JAMES MADISON 5:00 pm Athletic Facilities ..........................................................13 April 13 at UNC Greensboro * 6:00 pm 2017 Outlook ...............................................................14 Feb. 25 GEORGETOWN 2:00 pm April 14 at UNC Greensboro * 3:00 pm 2017 Wofford Roster ....................................................15 Feb. 26 UNC-ASHEVILLE 4:00 pm April 15 at UNC Greensboro * 1:00 pm Head Coach Todd Interdonato ..................................16-17 Feb. -

Dreher High School

Dreher High School A National School of Excellence June 2020 STUDENT BODY OFFICERS President Tasya Washington Secretary Mariah McKenzie SENIOR CLASS OFFICERS President Noah Dornik Vice President Jiniya Dunlap AP Capstone Diploma Recipients Ashton Butler Isabel Montague Lewis Davies Eleanor Pulliam Dana DeVeaux Callie Reid Ella DuBard Luke Reynolds Jackson Ellenberg Mary Shavo Sarah Germany Ariana Tata Abigail Kahn Johan Van Rosevelt Tyler Kendrick Madeline Voelkel Hayley Mason Tasya Washington Aidan McInnis Hannah Watts AP Capstone Diploma Candidates Rahul Bulusu Canaan Michel Flynn Burgess Meredith Osbaldiston Lucy Derrick Alexander Randall Madison Graham David Shealy Ana Hait Michael Shimizu George Hanna Elizabeth Thomson Mary Jones Sarah Walker Lillian King PALMETTO FELLOWS CANDIDATES William Bishop Hayley Mason Rahul Bulusu Aidan McInnis Flynn Burgess Canaan Michel John Cate Isabel Montague Lewis Davies Eleanor Pulliam Dana DeVeaux Alexander Randall Noah Dornik Callie Reid Ella DuBard Luke Reynolds John Ebinger Abigail Schroeder Jackson Ellenberg Mary Shavo Kourtlyn Ellis David Shealy Sarah Germany Michael Shimizu Hannah Gross Johan Van Rosevelt George Hanna Sarah Walker Caroline Hynes Tasya Washington Mary Jones Hanah Watts Tyler Kendrick Breana Woodard DAR Good Citizen Isabel Montague HIGH SCHOOL SCHOLARS/ACADEMIC ALL STARS Logan Acker Abigail Kahn Alexander Ackerman Tyler Kendrick James Beck Lillian King William Bishop Matthew Lacoste Danielle Blease Chase Lee Andrea Bocanegra Juarez Joseph Lenski Rahul Bulusu Hayley Mason Flynn -

Winthrop University

WINTHROP UNIVERSITY Independent Auditors' Report Financial Statements and Schedules For the Year Ended June 30, 2004 WINTHROP UNIVERSITY Table of Contents Page State Auditor’s Transmittal Letter FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditors' Report 1-2 Management=s Discussion and Analysis 3-7 Statement of Net Assets 8 Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Assets 9 Statement of Cash Flows 10-11 Component Unit - The Winthrop University Foundation Statement of Financial Position 12 Component Unit - The Winthrop University Foundation Statement of Activities 13-14 Component Unit - Winthrop University Real Estate Foundation, Inc. Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 15 Component Unit - Winthrop University Real Estate Foundation, Inc. Consolidated Statement of Activities 16 Notes to Financial Statements 17-40 Other Financial Information Supplementary Schedules Required by the Office of the South Carolina Comptroller General: Schedule of Information on Business-Type Activities Required For the Government-Wide Statement of Activities in the State CAFR 41 Schedule Reconciling the State Appropriation per the Financial Statements To the State Appropriation Recorded in State Accounting Records 42 SINGLE AUDIT SECTION Supplementary Federal Financial Assistance Reports: Schedule of Expenditures of Federal Awards 43-45 Report on Compliance and on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting Based on an Audit of Financial Statements Performed in Accordance With Government Auditing Standards 46-47 Report on Compliance With Requirements Applicable to Each Major Program and Internal Control Over Compliance in Accordance With OMB Circular A-133 48 Notes to Schedule of Expenditures Of Federal Awards 49 Summary Schedule of Prior Audit Findings 50 Schedule of Findings and Questioned Costs 51 Addendum 52-53 Members Albert B. -

Anniversary Celebration S

J1<6<l0~ C{,/}55 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Anniversary Celebration S. C. STATE LIBRARY October 23, 1997 6:00p.m. SEP _1 4 1999 Adam 's Mark Hotel STATE DOCUMENTS 1200 Hampton Street Columbia, South Carolina "Serving the Citizens of South Carolina" \t- o\ ~outb ~q~ ~\~ PROCLAMATION 0/i;,A BY y GovERNOR DAVID M. BEASLEY WHEREAS, the South Carolina Human Affairs Commission was created in 1972 to "to eliminate and prevent discrimination" and as the embodiment of "the concern of the state for promotion of harmony and the betterment of human affairs;" and WHEREAS, dt'ring the past two and a half decades, thousands of citizens, individual and corporate, have directly used the services of the South Carolina Human Affairs Commission; and WHEREAS, since its inception the Commission has consistently fulfilled a positive leadership role in the progress of this state, successfully addressing sensitive and often potentially polarizing issues in a manner which has benefited all South Carolinians; and WHEREAS, the dedication, accomplishments and service of Commission employees have earned for it a well-deserved reputation as one of the best such agencies in the nation; and WHEREAS, this extraordinary record was built by people whose distinguished service with and to the Commission brought great credit to the agency; and WHEREAS, this year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the creation of the South Carolina Human Affairs Commission and twenty-five years of exceptional service to the state of South Carolina. NOW, THEREFORE, I, David M. Beasley, Governor of the Great State of South Carolina, do hereby proclaim October 19- 25, 1997 as HUMAN AFFAIRS WEEK throughout the state in recognition of the South Carolina Human Affairs Commission and those South Carolinians who have been of service to the Commission and the people of the Palmetto State. -

School Desegregation in Forty-Three Southern Cities Eighteen Years After Brown

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 646 UD 012 821 TITLE It's Not Over in the South: School Desegregation in Forty-Three Southern Cities Eighteen Years After Brown. INSTITUTION Alabama Council on Human Relations, Inc., Huntsville.; American Friends Service Committee, Washington, D.C.; National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, New York, N.Y.; National Council of Churches of Christ, New York, N.Y.; Southern Regional Council, Atlanta, Ga.; Washington Research Project, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Southern Education Foundation, Atlanta, Ga.; Urban Coalition, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE May 72 NOTE 146p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Ability Grouping; Bus Transportation; Court Role; Discipline Problems; Expulsion; Faculty Integration; Integration Plans; *Integration Studies; Negro Students; Racial Balance; *School Integration; *School Segregation; *Southern Schools; Suspension; Token Integration; *Urban Schools IDENTIFIERS Florida; Geogia; Louisiana; South Carolina ABSTRACT The focus of this study on school desegregation is on 43 cities in the following areas: Bibb and Chatham Counties (Ga.) ; Orange, Duval, Hillsborough, and Pinellas Counties (Fla.); Cado, Quachita, East Baton Rouge, and Orleans Parishes (La.); and, Richland County District Number 1, Florence County District Number 1, and Orangeburg County District Number Five (S.C.) . Based on the reports of the study monitors, the following are among the recommendations and findings made:(1) equal protection of laws is yet not a reality for most black students in the South; -

B.S., Exercise Science, Winthrop

B.S. Exercise Science 1 Program Planning Summary Program Designation Degree Name: Bachelor of Science in Exercise Science CIP Code: 31.0505 Academic Unit: Department of Health and Physical Education Richard W. Riley College of Education Winthrop University Rock Hill, SC 29733 Proposed Date of Implementation: Fall 2008 or 2009? New Program or Modification: New Number of Credit Hours in Program: 125 (four year program) Justification of Need The principal goal of the Exercise Science (EXSC) Program is to provide students with sound academic preparation in the science of human movement. Students in the program will acquire knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSA’s) related to the theoretical and practical components of exercise science. Graduates will be leaders in the promotion and maintenance of health, physical activity, and fitness within their workplace and community settings or enroll in further study in exercise physiology or allied health professional graduate programs. The proposed curriculum will allow students to complete pre-requisites required for physical therapy, occupational therapy, and physician assistant programs. With the doubling of obesity in the United States over the last 20 years, well trained and dedicated professionals are needed in the areas of health promotion and exercise science. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2007), South Carolina’s most recent data for 2005 indicated a prevalence of obesity (defined by a Body Mass Index of 30 or higher) in 25-29% of the population. South Carolina’s neighboring states of North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia are in the same obesity category. Obesity in children ages 2- 18 years has tripled since 1980 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007).