Edifying Inheritance of Urali Tribe in Manethadam, Idukki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

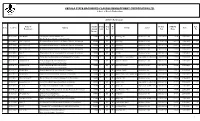

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

Able 7 - Live Stock Population a - Panchayats Cattle Sl

Table 7 - Live Stock Population A - Panchayats Cattle Sl. Buffaloes Goats Name of Panchayat Cross Breed Non Des cript Sheep No. Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 Mannamkandam 464 4054 126 1322 62 198 746 2090 2 Konnathady 476 4633 102 2170 55 430 996 2848 3 Kuttampuzha 352 1909 395 2298 47 104 848 2153 4 Baisonvally 254 2765 7 200 39 44 541 1699 5 Vellathuval 311 4205 53 812 39 165 1003 2439 6 Pallivasal 151 1251 46 456 4 26 320 994 Block Aadimali 2008 18817 729 7258 246 967 4454 12223 Table 7 (Contd..) Fowls No. of No. of No. of Sl. Milk co- Name of Panchayat Pigs Dogs slaughter veterinary No. Desi Improved Ducks op houses institution societies 1 2 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 1 Mannamkandam 161 3756 16678 5848 407 19 1 3 2 Konnathady 3704 3975 22112 3140 166 22 1 1 3 Kuttampuzha 1023 3967 20840 4069 139 1 0 4 Baisonvally 1022 2117 6848 2596 81 5 1 5 Vellathuval 1440 3366 14955 14093 293 6 1 6 Pallivasal 39 1614 7848 1935 478 1 1 Block Adimali 7389 18795 89281 31681 1564 54 2 7 A - Panchayats Cattle Sl. Buffaloes Goats Name of Panchayat Cross Breed Non Descript Sheep No. Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 Peruvanthanam 178 2562 229 1493 10 98 591 1180 2 Kumily 941 4893 307 1398 90 244 1115 2791 3 Kokkayar 94 1317 52 335 8 9 228 719 4 Peermade 643 1228 322 1596 24 36 207 529 5 Elappara 431 2591 117 2398 8 13 94 743 6 Vaddiperiyar 882 3927 914 4830 20 23 933 2200 Block Azhutha 3169 16518 1941 12050 160 423 3168 8162 Fowls No. -

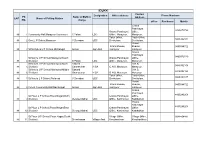

IDUKKI Contact Designation Office Address Phone Numbers PS Name of BLO in LAC Name of Polling Station Address NO

IDUKKI Contact Designation Office address Phone Numbers PS Name of BLO in LAC Name of Polling Station Address NO. charge office Residence Mobile Grama Panchayat 9495879720 Grama Panchayat Office, 88 1 Community Hall,Marayoor Grammam S.Palani LDC Office, Marayoor. Marayoor. Taluk Office, Taluk Office, 9446342837 88 2 Govt.L P School,Marayoor V Devadas UDC Devikulam. Devikulam. Krishi Krishi Bhavan, Bhavan, 9495044722 88 3 St.Michale's L P School,Michalegiri Annas Agri.Asst marayoor marayoor Grama Panchayat 9495879720 St.Mary's U P School,Marayoor(South Grama Panchayat Office, 88 4 Division) S.Palani LDC Office, Marayoor. Marayoor. St.Mary's U P School,Marayoor(North Edward G.H.S, 9446392168 88 5 Division) Gnanasekar H SA G.H.S, Marayoor. Marayoor. St.Mary's U P School,Marayoor(Middle Edward G.H.S, 9446392168 88 6 Division) Gnanasekar H SA G.H.S, Marayoor. Marayoor. Taluk Office, Taluk Office, 9446342837 88 7 St.Mary's L P School,Pallanad V Devadas UDC Devikulam. Devikulam. Krishi Krishi Bhavan, Bhavan, 9495044722 88 8 Forest Community Hall,Nachivayal Annas Agri.Asst marayoor marayoor Grama Panchayat 4865246208 St.Pious L P School,Pious Nagar(North Grama Panchayat Office, 88 9 Division) George Mathai UDC Office, Kanthalloor Kanthalloor Grama Panchayat 4865246208 St.Pious L P School,Pious Nagar(East Grama Panchayat Office, 88 10 Division) George Mathai UDC Office, Kanthalloor Kanthalloor St.Pious U P School,Pious Nagar(South Village Office, Village Office, 9048404481 88 11 Division) Sreenivasan Village Asst. Keezhanthoor. Keezhanthoor. Grama -

Kattappana School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 30001 Munnar G

Kattappana School Code Sub District Name of School School Type 30001 Munnar G. V. H. S. S. Munnar G 30002 Munnar G. H. S. Sothuparai G 30003 Munnar G. H. S. S. Vaguvurrai G 30005 Munnar G. H. S. Guderele G 30006 Munnar L. F. G. H. S . Munnar A 30007 Munnar K. E. H. S . Vattavada A 30008 Munnar G. H. S. S. Devikulam G 30009 Munnar G. H. S. S. Marayoor G 30010 Munnar S. H. H. S. Kanthalloor A 30011 Peermade St. George`s High School Mukkulam A 30012 Nedumkandam Govt. H.S.S. Kallar G 30013 Nedumkandam S.H.H.S. Ramakalmettu A 30014 Nedumkandam C.R.H.S. Valiyathovala A 30015 Nedumkandam G.H.S. Ezhukumvayal G 30016 Kattappana M.M.H.S. Nariyampara A 30017 Peermade St.Joseph`s H.S.S Peruvanthanam A 30018 Peermade G.H.S.Kanayankavayal G 30019 Peermade St.Mary`s H.S.S Vellaramkunu A 30020 Kattappana SGHSS Kattappana A 30021 Kattappana OSSANAM ENG MED HSS KATTAPPANA U 30022 Peermade Govt V.H.S.S. T.T. I. Kumaly G 30023 Nedumkandam N S P High School Vandanmedu A 30024 Nedumkandam S.A.H.S. Vandanmedu A 30025 Peermade C.P.M. G.H.S.S. Peermedu G 30026 Peermade M.E.M.H.S.S. Peermede U 30027 Peermade Panchayat H.S.S. Elappara A 30028 Peermade G.H.S.Vagamon G 30029 Peermade St. Sebastians H.S.S. Cheenthalar A 30030 Peermade Panchayat H.S.S. Vandiperiyar A 30031 Nedumkandam Govt. H S S And V H S S Rajakumary G 30032 Peermade St. -

Dictionary of Martyrs: India's Freedom Struggle

DICTIONARY OF MARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala ii Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 DICTIONARY OF MARTYRSMARTYRS INDIA’S FREEDOM STRUGGLE (1857-1947) Vol. 5 Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu & Kerala General Editor Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Chairman, ICHR Executive Editor Rajaneesh Kumar Shukla Member Secretary, ICHR Research Consultant Amit Kumar Gupta Research and Editorial Team Ashfaque Ali Md. Naushad Ali Md. Shakeeb Athar Muhammad Niyas A. Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF IDNIA AND INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH iv Dictionary of Martyrs: India’s Freedom Struggle (1857-1947) Vol. 5 MINISTRY OF CULTURE, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH First Edition 2018 Published by MINISTRY OF CULTURE Government of India and INDIAN COUNCIL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi - 110 001 © ICHR & Ministry of Culture, GoI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN 978-81-938176-1-2 Printed in India by MANAK PUBLICATIONS PVT. LTD B-7, Saraswati Complex, Subhash Chowk, Laxmi Nagar, New Delhi 110092 INDIA Phone: 22453894, 22042529 [email protected] State Co-ordinators and their Researchers Andhra Pradesh & Telangana Karnataka (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) V. Ramakrishna B. Surendra Rao S.K. Aruni Research Assistants Research Assistants V. Ramakrishna Reddy A.B. Vaggar I. Sudarshan Rao Ravindranath B.Venkataiah Tamil Nadu Kerala (Co-ordinator) (Co-ordinator) N. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Idukki District from 10.04.2016 to 16.04.2016

Accused Persons arrested in Idukki district from 10.04.2016 to 16.04.2016 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kanimalayil House, Koovappuram Cr. 165/16 19/16, Bhagam, 10.04.2016 U/S 279 IPC C T Sanjay Bailed By 1 Martin Paul Koovappuram Kaliyar Male Koovappuram kara, 16.50 Hrs. & 3(1) R/W SI of Police Police. Vannappuram 181 MV Act Village. Vandanamthadathil House, Cr. 165/16 Plantationkavala 52/16, 10.04.2016 U/S 279 IPC C T Sanjay Bailed By 2 Joy Sebastian Bhagam, Mundanmudi Kaliyar Male 17.30 Hrs. &185 (a) MV SI of Police Police. Vannappuram kara, Act Vannappuram Village. THADATHIL HOUSE, THOTTUKARA P R SAJEEVAN JFMC 42 BHAGAM,MEMADAN PUTHUPPARIY 11.04.2016 592/16, THODUPUZH SI 3 BINOY JOSEPH JOSEPH THODUPUZH MALE GU ARAM 10.40 279,185,3(1),181 A PS TRAFFIC,THOD A KARA,ARAKKUZHA UPUZHA VILLAGE THAVANIMADATHIL HOUSE, P R SAJEEVAN NEAR JFMC 42 MYLAKKOMBU 11.04.2016 593/16, THODUPUZH SI 4 AJI THANKAPPAN NEWMAN THODUPUZH MALE KARA,PARA 11.55 279,185,3(1),181 A PS TRAFFIC,THOD COLLAGE A BHAGAM,KUMARAM UPUZHA ANGALAM VILLAGE THOTTIPPARAMBIL HOUSE, C S RAJAN, SI JFMC 36 VENGALLOOR KARA, TEMPLE 11.04.2016 595/16, THODUPUZH CONTROL 5 RAJEEVE GOPI THODUPUZH MALE SHAPPUMPADY FRONT 18.30 279,185,3(1),181 A PS ROOM A BHAGAM,KUMARAM THODUPUZHA ANGALAM VILLAGE Chakkiyanikunnel N.V.Shajimon, House, Karikulam 11/04/16- 6 Manoj Karunakaran 42, Male Kannamkulam Vagamon Addl S.I of Bailed Bhagom, Pazhavangadi 2.40 PM Police, Vagamon Village, Ranni. -

List of Biogas Plants Installed in Kerala During 2008-09

LIST OF BIOGAS PLANTS INSTALLED IN KERALA DURING 2008-09 by Si ze Block Model Sr. No latrine g date Village amount Dist rict Dist & Name Subsidy Address Category Guidence Technical Technical Inspected Inspected Functionin Beneficiary Beneficiary 1 Trivandrum Vijayakumar.N, S/o Neyyadan Nadar, Vijaya Bhavan, Neyyattinkar Parassala HA 2m3 KVIC 0 3500 26.11.08 K.Somasekhar P.Sanjeev, ADO Neduvanvila, Parassala P.O & Pancht, Neyyattinkara Tq- a anPillai (BT) 695502 2 Trivandrum Sabeena Beevi, Kunnuvila Puthenveedu, Edakarickam, Kilimanoor Pazhayakunnu GEN 3m3 KVIC 0 2700 28.10.08 K.Somasekhar P.Sanjeev, ADO Thattathumala.P.O, Pazhayakunnummel Pancht, mmel anPillai (BT) Chirayinkeezhu Tq 3 Trivandrum Anilkumar.B.K, S/o Balakrishnan, Therivila House, Athiyannur Athiyannur HA 2m3 DB 0 3500 17.01.09 K.Somasekhar P.Sanjeev ADO Kamukinkode, Kodangavila.P.O, Athiyannur Pancht, anPillai (BT) Neyyattinkara Tq 4 Trivandrum Sathyaraj.I, S/o Issac, kodannoor Mele Puthenveedu, Perumkadav Perumpazhuth HA 2m3 DB 0 3500 18.01.09 K.Somasekhar P.Sanjeev ADO Punnaikadu, Perumpaxhuthoor.P.O, Neyyattinkara Pancht & ila oor anPillai (BT) Tq 5 Trivandrum Balavan.R.P, S/o Rayappan, 153, Paduva House, Neyyattinkar Athiyannur HA 2m3 DB 0 3500 04.02.09 K.Somasekhar P.Sanjeev ADO Kamukincode, Kodungavila.P.O, Athiyannur Pancht, a anPillai (BT) Neyyattinkara Tq-695123 6 Trivandrum Ani.G, S/o Govindan.K, Karakkattu Puthenveedu, Avanakuzhy, Athiyannur Athiyannur HA 2m3 DB 0 3500 08.02.09 K.Somasekhar P.Sanjeev ADO Thannimoodu.P.O, Athiyannur Pancht, Neyyattinakara Tq anPillai -

Environmental Pollution Due to Pesticide Application in Cardamom Hills of Idukki, District, Kerala, India

Journal of Energy Research and Environmental Technology (JERET) Print ISSN: 2394-1561; Online ISSN: 2394-157X; Volume 2, Number 1; January-March, 2015; pp. 54-62 © Krishi Sanskriti Publications http://www.krishisanskriti.org/jeret.html Environmental Pollution due to Pesticide Application in Cardamom Hills of Idukki, District, Kerala, India Susan Jacob1, Resmi.G2 and Paul K Mathew3 1Research Scholar, Karpagam University, Coimbatore 2NSS College of Engineering Palakkad 3MBC College of Engineering & Technology, Peermade E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Intensive agricultural practices often include the use of degradation or metabolism once released into the pesticides to enhance crop yields. However, the improvement in yield environment. The objective of present study is, is associated with the occurrence and persistence of pesticide residues in soil and water. Kerala, being the largest production centers of cardamom in India and cardamom the highest pesticide Identify contaminated areas and sources of contamination. consuming crop, the risk of environmental contamination especially Investigate residual levels of pesticide in the environment, in soil and water is high. The objective of the study was to determine soil and water. the present contamination levels in water and soil samples of Locating probable places of highly contaminated area Cardamom plantations in Idukki district. Sampling points were using GIS applications. selected on purposive sampling technique from the entire plantation The fate of pesticides in soil and water environments is area in the district. 100 water samples and 38 soil samples were influenced by the physio-chemical properties of the pesticide, collected from the cardamom plantations or from adjacent water the properties of the soil and water systems (presence of clay sources and analysed for pesticide residues. -

Self Study Report

GOVERNMENT COLLEGE KATTAPPANA Kattappana P. O., Idukki, Kerala – 685508 Ph: +91 4868 272347; e-mail: [email protected] www.gckattappana.ac.in (Affiliated to Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam) SELF STUDY REPORT Submitted to NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AND ACCREDITATION COUNCIL December 2015 Contents Page Preface 1 Executive Summary 3 SWOC Analysis of the Institution 12 Profile of the Affiliated College 17 Criteria-wise Inputs Criterion I Curricular Aspects 23 Criterion II Teaching, Learning and Evaluation 36 Criterion III Research, Consultancy and Extension 67 Criterion IV Infrastructure and Learning Resources 105 Criterion V Student Support and Progression 124 Criterion VI Government, Leadership and Management 144 Criterion VII Innovations and Best Practices 168 Evaluative Report of the Departments Department of Chemistry 177 Department of Commerce 183 Department of Economics 196 Department of Malayalam 205 Department of Mathematics 222 Department of English and Department of Hindi 232 Declaration by the Head of the Institution 238 Certificate of Compliance 239 Annexures 240 PREFACE The district of Idukki is blessed with beautiful national parks and the picturesque forests stretch far and wide across the district. It has rightly been called the spice garden of the state of Kerala, famous for pepper, cardamom and many other spices. Idukki is a famous tourist destination also with its moderate climate and beautiful landscape. The migration from the plains to the high ranges started during the 1950s and the district of Idukki was formed in 1972. The Devaswom Board College, situated at Nariyampara near Kattappana and managed by the Travancore Devaswom Board, was the only higher education institution in the high ranges of the district at that time. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City District from 27.03.2016 to 02.04.2016

Accused Persons arrested in Thiruvananthapuram City district from 27.03.2016 to 02.04.2016 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Sec Police father of which Time of Officer, Rank which No. Accused Sex Accused of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Vilayil Veedu, 524/16 Sumesh 32/16 Medical College Medical 27/03/16 1 Sukumaran 279 IPC MCPS Sainulabdeen ACJMC Kumar Male Ward, Cheruvakal College 08.50 hrs Village Kattuvila Puthen Medical Colege 525/16 46/16 27/03/16 2 Rajan Kochuraman Veedu, Kallampalli, Car Parking 15 © of Abkari MCPS S. Bijoy ACJMC Male 14.50 hrs Ulloor Village area Act Gowri Bhavan, 526/16 Jayakumar C Chandrasekhar 42/16 Medical 27/03/16 Jayakumaran 3 Dhanuvachapuram 118(a) of KP MCPS ACJMC Nair an Nair Male College Jn 15.20 hrs Nair , Kollayil Village Act Reshma Bhavan, 527/16 51/16 Medical 27/03/16 4 Rajarajan Chakrapani Nettayam Desam, 279 IPC & 185 MCPS S. Bijoy ACJMC Male College Jn 15.50 hrs Peroorkada Village of MV Act Kovil Vilakam 528/16 49/16 Veedu, Akkulam 27/03/16 5 Ajith Kumar Thankappan Ulloor Jn 15 © of Abkari MCPS Sainulabdeen ACJMC Male Road, Ulloor, 16.10 hrs Act Cheruvakal Village Giri Bhavan, ARR 12, Kalakaumudi 529/16 Mohana 32/16 27/03/16 6 Rakesh Road, Medical Chennilode 118(a) of KP MCPS S.Bijoy ACJMC Chandran Male 16.50 hrs College Ward, Act Pattom Village Ramya Mandiram, TC 14/957, 530/16 32/16 Chennilode Desam, 27/03/16 Jayakumaran 7 Ranjith Gangadaran Kumarapuram 279 -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 18.07.2021To24.07.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 18.07.2021to24.07.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr. 253/2021 Kochu Poovathussery P R U/s. 188, 269 House, Cherukara, 24-07-2021 Mohanakumar, JFMC 1 Sabinoraj Somaraj 22 Male Cherukara IPC, Sec. KAINADI Neelamperoor Wd XII, 22:10 SI of Police, RAMANKARY 4(2)(j), 5 KEDO Kavalam Village Kainady 2021 Cr. 252/2021 Kamathussery House, P R U/s. 188, 269 Cherukara, 24-07-2021 Mohanakumar, JFMC 2 Aswin Shajimon 20 Male Kainady IPC, Sec. KAINADI Neelamperoor Wd XII, 21:35 SI of Police, RAMANKARY 4(2)(j), 5 KEDO Kavalam Village Kainady 2021 Cr. 723/2021 U/s. Sec. 4(2)(j) Kaduvankal house, r/w 5 of Kerala 24-07-2021 KUTHIATHOD Santhosh JFMC I 3 Sebastian Martin 20 Male kuthiyathode p/w Pallithode Epidemic 17:50 E kumar P CHERTHALA 16,Pallithode p o Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr. 639/2021 U/s. 279,283 IPC 1860 & THARAYIL VEEDU, 177(A),179(1) PATTANAKKAD PO, 25-07-2021 PATTANAKAD SREEKUMAR, SI JFMC I 4 LENIN THANKAPPAN 52 Male PATTANAKKAD OF The Motor PATTANAKKAD P/W- 18:50 U OF POLICE CHERTHALA Vehicle Act 13, 1988 (Amendment 2015,2019) Cr. 1159/2021 CHIRAYIL KARIYIL NEDUMBRAKK 24-07-2021 U/s. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Idukki District from 22.12.2019To28.12.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Idukki district from 22.12.2019to28.12.2019 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Manakkudu 1521/2019 village,manakkudu 22-12-2019 U/s 279 THODUPU 20, KSRTC BAILED BY 1 Aji Kuttappan Kara,nellikkavu at 08:55 IPC,21(25) ZHA Raju.p Male junction POLICE bhagam,mannatham Hrs r/w 184(c) of (Idukki) kunnel house m v act 303/2019 Vazhakkalayil (H) 22-12-2019 UDUMBAN 54, Udumbanchol U/s Joby K J ,SI BAILED BY 2 Baby Joseph Avanakkumchal at 10:45 CHOLA Male a 323,324,34 OF POLICE POLICE colony Rajakumary Hrs (Idukki) IPC Pannaipuram 190/2019 Bhagam,Kariyanam 22-12-2019 U/s 279 CUMBUMM 20, SI Jacob BAILED BY 3 Sudarsan Maheswaran Petty Chennakulzm at 10:50 IPC&3(1) ETTU Male Kuruvila POLICE Kara,Uthamapalam Hrs R/W 181 Of (Idukki) Village,Thamilnadu MV Act. House No. 35/02, 377/2019 MUHAMMA 22-12-2019 NAGOOR 32, Thankammal Street U/s 279 IPC MARAYOO V M BAILED BY 4 D melady at 11:00 MEERAAN Male , Udumal petta, & 185 MV R (Idukki) MAJEED S I POLICE HANEEFA Hrs Tamil Nad ACT UGP V/507. 309/2019 Anil George, 22-12-2019 UDUMBAN Vijayakumar 48, Adukidanthan, Udumbanchol U/s 279 IPC, IP BAILED BY 5 Subbaswamy at 11:00 CHOLA S Male udumbanchola, a 132(1) of MV Udumbanchol POLICE Hrs (Idukki) Chathuragspara Act a AADHI BHAVAN HOUSE 302/2019 MOONNUKALLU 22-12-2019 U/s T S Babay SI PANDARA