Introduction: Mozart's Requiem in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Washington School of Music St. Mark's Cathedral

((J i\A~&!d C\I~ t \LqiJ }D10 I I . I'J. University of Washington School of Music in conjunction with St. Mark's Cathedral November 11-12, 2016 Dr. Carole Terry Wyatt Smith Co-Directors On behalfof the UW School of Music, I am delighted to welcome you to this very special Reger Symposium. Professor Carole Terry, working with her facuIty colleagues and students has planned an exciting program of recitals, lectures, and lively discussions that promise to illuminate the life and uniquely important music of Max Reger. I wish to thank all of those who are performing and presenting as well those who are attending and participating in other ways in our two-day Symposium. Richard Karpen Professor and Director School of Music, University ofWashington This year marks the lOOth anniversary of the death of Max Reger, a remarkable south German composer of works for organ and piano, as well as symphonic, chamber, and choral music. On November J ph we were pleased to present a group of stellar Seattle organists in a concert of well known organ works by Reger. On November 12, our Symposium includes a group of renowned scholars from the University of Washington and around the world. Dr. Christopher Anderson, Associate Professor of Sacred Music at Southern Methodist University, will present two lectures as a part of the Symposium: The first will be on modem performance practice of Reger's organ works, which will be followed later in the day with lecture highlighting selected chamber works. Dr. George Bozarth will present a lecture on some of Reger's early lieder. -

Calmus-Washington-Post Review April 2013.Pdf

to discover, nurture & promote young musicians Press: Calmus April 21, 2013 At Strathmore, Calmus Ensemble is stunning in its vocal variety, mastery By Robert Battey Last week, two of Germany’s best musical ensembles — one very large, one very small — visited our area. After the resplendence of the Dresden Staatskapelle on Tuesday at Strathmore, we were treated on Friday to an equally impressive display of precise, polished musicianship by the Calmus Ensemble, an a cappella vocal quintet from Leipzig. Founded in 1999 by students at the St. Thomas Church choir school (which used to be run by a fellow named Bach), Calmus presented a program both narrow and wide: all German works, but spanning more than four centuries of repertoire. The group held the audience at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Alexandria nearly spellbound with its artistry. The only possible quibble was that occasionally there was a very slight imbalance in the upper texture; Calmus has only one female member, the alto parts being taken by a countertenor who could not always match the clear projection of the soprano. But in matters of pitch, diction and musical shaping, I’ve never heard finer ensemble singing. From the lively “Italian Madrigals” of Heinrich Schütz, to a setting by Johann Hiller of “Alles Fleisch” (used by Brahms centuries later in “Ein Deutsches Requiem”), to the numinous coloratura of Bach’s “Lobet den Herrn,” to some especially lovely part-songs of Schumann, to a performance-art work written for the group by Bernd Franke in 2010, the quintet met the demands of every piece with cool perfection. -

Eftychia Papanikolaou Is Assistant Professor of Musicology and Coordinator of Music History Studies at Bowling Green State University in Ohio

Eftychia Papanikolaou is assistant professor of musicology and coordinator of music history studies at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. Her research (from Haydn and Brahms to Mahler’s fi n-de-siècle Vienna), focuses on the in- terconnections of music, religion, and politics in the long nineteenth century, with emphasis on the sacred as a musical topos. She is currently completing a monograph on the genre of the Romantic Symphonic Mass <[email protected]>. famous poetic inter- it was there that the Requiem für Mignon polations from Johann (subsequently the second Abteilung, Op. The Wolfgang von Goethe’s 98b), received its premiere as an inde- Wilhelm Meisters Leh- pendent composition on November 21, rjahre [Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship], 1850. With this dramatic setting for solo especially the “Mignon” lieder, hold a voices, chorus, and orchestra Schumann’s prestigious place in nineteenth-century Wilhelm Meister project was completed. In lied literature. Mignon, the novel’s adoles- under 12 minutes, this “charming” piece, cent girl, possesses a strange personality as Clara Schumann put it in a letter, epito- whose mysterious traits will be discussed mizes Schumann’s predilection for music further later. Goethe included ten songs in that defi es generic classifi cation. This Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, eight of which article will consider the elevated status were fi rst set to music by Johann Fried- choral-orchestral compositions held in rich Reichardt (1752–1814) and were Schumann’s output and will shed light on included in the novel’s original publication tangential connections between the com- (1795–96). Four of those songs are sung poser’s musico-dramatic approach and his by the Harper, a character reminiscent of engagement with the German tradition. -

Concerts Lux Aeterna Requiem

ASTASTRRRRAAAA CONCERTS 2 0 1 3 555 pm, Sunday 888 DecDecemberember SACRED HEART CHURCH Carlton, Melbourne György Ligeti LUX AETERNA Dan Dediu O MAGNUM MYSTERIUM Thomas Tallis O NATA LUX TE LUCIS ANTE TERMINUM Ruth Crawford-Seeger CHANTS DIAPHONY Max Reger REQUIEM Heitor Villa-Lobos PRAESEPE Catrina Seiffert, Elizabeth Campbell, Jerzy Kozlowski Mardi McSuMcSulllllea,lea, Elise Millman, Alister Barker The Astra Choir and ensemble Catrina Seiffert soprano Elizabeth Campbell mezzo-soprano Jerzy Kozlowski bass Mardi McSullea flute Elise Millman bassoon , Alister Barker cello Aaron Barnden violin , Phoebe Green viola, Nic Synot double bass , Craig Hill clarinet , Robert Collins trombone , Kim Bastin piano , Joy Lee organ The Astra Choir soprano Irene McGinnigle, Gabriella Moxey, Susannah Polya, Catrina Seiffert, Kristy de la Rambelya, Yvonne Turner Jenny Barnes, Louisa Billeter, Jean Evans, Maree Macmillan, Kate Sadler, Haylee Sommer alto Amy Bennett, Laila Engle, Gloria Gamboz, Anna Gifford, Judy Gunson, Xina Hawkins, Katie Richardson Beverley Bencina, Heather Bienefeld, Jane Cousens, Joy Lee, Joan Pollock, Sarah Siddiqi , Aline Scott-Maxwell tenor Stephen Creese, Greg Deakin, Matthew Lorenzon, Ronald McCoy, Ben Owen, Richard Webb, Simon Johnson bass Robert Franzke, Steven Hodgson, Nicholas Tolhurst, Stephen Whately Jerzy Kozlowski Tim Matthews Staindl, Chris Rechner, Chris Smith, John Terrell conducted by John McCaughey Concert Manager: Margaret Lloyd Recording: Michael Hewes, Steve Stelios Adam Astra Manager: Gabrielle Baker Front of House: Stiabhna Baker-Holland, George Baker-Holland 2 PROGRAM György Ligeti LUX AETERNA (1966) 16-part choir Dan Dediu O MAGNUM MYSTERIUM (2013) 6-part choir Thomas Tallis O NATA LUX (1575) vespers hymn, 5-part choir Ruth Crawford DIAPHONIC SUITE No.1 (1930) solo flute I. -

Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger's Requiems

Historicism and German Nationalism in Max Reger’s Requiems Katherine FitzGibbon Background: Historicism and German During the nineteenth century, German Requiems composers began creating alternative German Requiems that used either German literary material, as in Schumann’s Requiem für ermans have long perceived their Mignon with texts by Goethe, or German literary and musical traditions as being theology, as in selections from Luther’s of central importance to their sense of translation of the Bible in Brahms’s Ein Gnational identity. Historians and music scholars in deutsches Requiem. The musical sources tended the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to be specifically German as well; composers sought to define specifically German attributes in made use of German folk materials, German music that elevated the status of German music, spiritual materials such as the Lutheran chorale, and of particular canonic composers. and historical forms and ideas like the fugue, the pedal point, antiphony, and other devices derived from Bach’s cantatas and Schütz’s funeral music. It was the Requiem that became an ideal vehicle for transmitting these German ideals. Although there had long been a tradition of As Daniel Beller-McKenna notes, Brahms’s Ein German Lutheran funeral music, it was only in deutsches Requiem was written at the same the nineteenth century that composers began time as Germany’s move toward unification creating alternatives to the Catholic Requiem under Kaiser Wilhelm and Bismarck. While with the same monumental scope (and the same Brahms exhibited some nationalist sympathies— title). Although there were several important he owned a bust of Bismarck and wrote the examples of Latin Requiems by composers like jingoistic Triumphlied—his Requiem became Mozart, none used the German language or the Lutheran theology that were of particular importance to the Prussians. -

A Guide to Franz Schubert's Religious Songs

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks A GUIDE TO FRANZ SCHUBERT’S RELIGIOUS SONGS by Jason Jye-Sung Moon Submitted to the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music in Voice December 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music in Voice. __________________________________ Mary Ann Hart, Chair & Research Director __________________________________ William Jon Gray __________________________________ Robert Harrison __________________________________ Brian Horne ii Copyright © 2013 by Jason Jye-Sung Moon All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee chair and research director, Professor Mary Ann Hart, for the excellent guidance, caring, patience, and encouragement I needed to finish this long journey. I would also like to thank Dr. Brian Horne, who supported me with prayers and encouragement. He patiently corrected my writing even at the last moment. I would like to thank my good friend, Barbara Kirschner, who was with me throughout the writing process to help me by proofreading my entire document and constantly cheering me on. My family was always there for me. I thank my daughters, Christine and Joanne, my parents, and my mother-in-law for supporting me with their best wishes. My wife, Yoon Nam, deserves special thanks for standing by me with continuous prayers and care. I thank God for bring all these good people into my life. -

Philharmonic Concert

________ Geza Hosszu Legocky "aka" Gezalius ________ _______________ Piotr Kalina, tenor _______________ _________________ Organised by ______________ Geza Hosszu Legocky already impresses the most demanding audiences He comes from Kraków. His artistic achievements are based on many solo whilst affirming a non-conventional mind-set with various musical genres. concerts, in places such as Kraków Philharmonic, Podkarpacka Philharmo- Born in Switzerland as an American citizen from Hungarian-Ukrainian pa- nic, Silesian Philharmonic, Zabrze Philharmonic and NOSPR chamber hall. for Auschwitz rents, Geza Hosszu Legocky began to attract the audience at the age of 6, In his repertoire, he has integrated arias from many opera and oratorio after entering the Vienna Music Academy as an especially gifted violin pro- pieces, including "Norma", "Tosca", "Die Zauberflöte", "Messa da Requiem" digy. At the age of 14 he made his big debut performances with the NHK (G. Verdi), "Stabat Mater" (G. Rossini), "Elias" (F. Mendelssohn-Bartholdy) Philharmonic Orchestra with Charles Dutoit, and also with other Orchestras such as The and "Das Lied von der Erde" (G. Mahler). He worked with many outstan- Radio France Philharmonic Orchestra under M. w. Chung, The Swiss-Italian Radio Orchestra ding conductors. He participated in many masterclasses with, inter alia, under Jacek Kapszsyk, just to name a few. His exceptional gift for music and his capacity to Piotr Beczała, Teru Yosihara and Markus Schäfer. He learned the art of sin- transmit his emotions directly into the heart of his audiences lead him to work in his early ging from Jolanta Kowalska-Pawlikowska and from Jacek Ozimkowski. He _________________ ______________ career with living legends such as Martha Argerich, Mischa Maisky, Charles Dutoit, Yehudi was awarded at different vocal competitions. -

Requiem Woo V/9

Max Reger (1873–1916) Requiem WoO V/9 Vervollständigung der Sequenz zum Konzertgebrauch von Thomas Meyer-Fiebig Einleitung I. Bekanntlich waren Tod und Vergänglichkeit ein zentrales Thema in Max Regers Denken und Schaffen.1 Schon im langsamen Satz der 1894-5 entstandenen Orgelsuite e-Moll op. 16 findet sich neben den Choralmelodien Es ist das Heil uns kommen her und Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir die achte Strophe des Chorals O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden, »Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden«; rund zwanzig Jahre später war die Aktualität dieser Choralstrophe nicht geringer geworden, an Arthur Seidl schrieb Reger 1913: »Haben Sie noch nicht bemerkt, wie durch alle meine Sachen der Choral durchklingt „Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden?“«2 Selbst in der Verlobungszeit schuf Reger zahlreiche Choralvorspiele, die dem Themenbereich nahestehen: »Ich hab in den letzten Tagen Sachen geschrieben, die fast durchgängig vom Tode handeln! Sei mir nicht böse, ich bin eben so tiefernst! | Du mußt mich „aufhellen“, mußt meine Verdüsterung u. Schwarzseherei langsam ablösen – u. ich weiß, Dir, aber nur Dir allein, gelingt es!«3 Stimmungsaufhellungen sollten bei dem hochsensiblen Musiker immer wieder nur temporär sein, nicht nur musikalisch kreisten seine Gedanken immer wieder um Tod und Vergänglichkeit. Es ist bezeichnend, wie ironisch sich Karl Straube später zu Regers Empfindungen äußerte; an Günther Ramin schrieb er 1928: »Günter Raphael hat sein Violinkonzert vollendet. Ein erstaunlicher Mensch. Von einer Maßlosigkeit des Schaffens wie Max Reger. Sollte auch er unbewußt Todesnähe ahnen?«4 Schon vor Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges, während seines Kuraufenthalts im 1 Vgl. Rainer Cadenbach, Memento und Monumentum. -

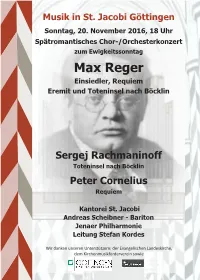

Programmheft Reger-Requiem 10,5Pt.Cdr

Musik in St. Jacobi Göttingen Sonntag, 20. November 2016, 18 Uhr Spätromantisches Chor-/Orchesterkonzert zum Ewigkeitssonntag Max Reger Einsiedler, Requiem Eremit und Toteninsel nach Böcklin Sergej Rachmaninoff Toteninsel nach Böcklin Peter Cornelius Requiem Kantorei St. Jacobi Andreas Scheibner - Bariton Jenaer Philharmonie Leitung Stefan Kordes Wir danken unseren Unterstützern: der Evangelischen Landeskirche, dem Kirchenmusikförderverein sowie PROGRAMM Max Reger (1873-1916) Die Toteninsel op. 128/3 (1912) aus „Vier Tondichtungen nach Arnold Böcklin” Max Reger Der Einsiedler op. 144a (1915) für Chor, Bariton und Orchester Sergej Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) Die Toteninsel op. 29 (1909) nach Arnold Böcklin - Pause (ca. 15 min.) - Besichgen Sie in der Pause gerne unsere Ausstellung in den Seitenschiffen: „125 Jahre Kantorei St. Jacobi“ (Die Ausstellung ist noch bis zum 25.11. geöffnet.) Peter Cornelius (1824-1874) Requiem (1872) nach Hebbel Max Reger Der geigende Eremit op. 128/1 (1912) aus „Vier Tondichtungen nach Arnold Böcklin” Max Reger Requiem op. 144b (1915) nach Hebbel für Chor, Bariton und Orchester 2 Zum heugen Konzert Vor genau 110 Jahren, am 20.11.1906, dirigierte Max Reger im Stadheater Göngen das Städsche Orchester (verstärkt durch die Kasseler Hoapelle) mit eigenen Werken. Am 11. Mai 1916 starb er im Alter von gerade einmal 43 Jahren. Wer war dieser Komponist, der in seiner kurzen Lebenszeit weit über 1.000 Werke für nahezu alle Gaungen komponiert hat (er nannte sich scherzha „Akkordarbeiter“) und der heute hauptsächlich für seine großen Orgelwerke bekannt ist? Max Reger wurde 1873 in Weiden in der Oberpfalz geboren. Er studierte beim damali- gen „Papst der Musiktheorie“ Hugo Riemann in Sondershausen und Wiesbaden. -

Max Reger's Opus 135B and the Role of Karl Straube a Study of The

STM 1994–95 Max Reger’s Opus 135b and the Role of Karl Straube 105 Max Reger’s Opus 135b and the Role of Karl Straube A study of the intense friendship between a composer and performer that had potentially dangerous consequences upon the genesis of Reger’s work Marcel Punt Max Reger’s “Fantasie und Fuge in d-moll, op. 135b” for organ appears at a very cru- cial moment in the history of German music. Reger wrote this piece between 1914 and 1916, a period in which tonality had to give way to other principles of composi- tion, such as unity creating intervals, twelve-tone music, variable ostinato, tone co- lour-melodies, etc. With this piece, Reger stands in the middle of this “development” from Wagner to Schönberg and Webern. So although the piece is still based on tona- lity, it already shows some aspects of the music that was to supersede it, namely both the fantasy and the fugue, which are based on the interval of a small second, the first theme of the fugue which consists of 11 different tones, the second which consists of even 12 different tones, and Reger’s way of changing sound together with the phrasing and the harmonic progress of the music. Reger’s opus 135b for organ could be regar- ded as one of his most advanced and still deserves more attention than it has received to date. Most organists will still only know the piece in its definite shape, now available in the Peeters-edition. But the manuscript that was first sent to the editor Simrock in Berlin, differs quite substantially from the version that Simrock finally published. -

War Requiem”—Benjamin Britten (1963) Added to the National Registry: 2018 Essay by Neil Powell (Guest Post)*

“War Requiem”—Benjamin Britten (1963) Added to the National Registry: 2018 Essay by Neil Powell (guest post)* In October 1958, Benjamin Britten was invited to compose a substantial work for chorus and orchestra to mark the consecration of Coventry’s new cathedral, designed by Sir Basil Spence and intended to replace the building destroyed by German bombing in 1940. He accepted at once: the commission resonated deeply with Britten, a lifelong pacifist who intended to dedicate it to three friends killed in the Second World War. But by the time he began work on what was to become the “War Requiem,” in the summer of 1960, his interest in the project had been both complicated and deepened by two factors: one was his re-reading of Wilfred Owen’s war poems, which he proposed to interleave with the traditional movements of the Latin Requiem Mass; the other was the suicide of his friend Piers Dunkerley, whom Britten regarded as a delayed casualty of the war and who became the work’s fourth dedicatee. A very public commission had thus acquired a very private subtext. It was surely at this point that Britten began to think of his “War Requiem” as (in his own words) “a kind of reparation.” At the foreground of the work are an English and a German soldier, intimately accompanied by a chamber orchestra: in keeping with his overarching theme of reconciliation, Britten decided that these two male soloists should be his partner, the tenor Peter Pears, and the German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Beyond them are the performers of the liturgical texts--soprano soloist, chorus, symphony orchestra--and, more distant still, boys’ chorus and organ. -

Max Reger (Geb

Max Reger (geb. Brand in der Oberpfalz, 19. März 1873 — gest. Leipzig, 11. Mai 1916) »Der Einsiedler« op. 114a (p. 1-33) für Bariton, fünfstimmigen gemischten Chor und Orchester (1914-15) auf eine Dichtung von Joseph von Eichendorff (1788-1857) Requiem »Seele, vergiß sie nicht« op. 144b (p. 3-37) für Altsolo, gemischten Chor und Orchester (1914-15) auf eine Dichtung von Friedrich Hebbel (1813-63) Vorwort Nach dem seinerzeit vom Verlag Lauterbach & Kuhn abgelehnten Gesang der Verklärten op. 71 (1903, Text von Busse) und direkt im Anschluß an den gigantischen 100. Psalm op. 106 (vollendet am 22. Juni 1909) waren Die Nonnen op. 112 (vollendet am 7. August 1909, Text von Martin Boelitz) das dritte großangelegte chorsymphonische Werk Max Regers, denen dann noch Die Weihe der Nacht op. 119 (1911, Text von Friedrich Hebbel), ein unvollendet gebliebenes lateinisches Requiem (1914) sowie die beiden hier erstmals in einer gemeinsamen Studienpartitur vorgelegten Werke op. 144, Der Einsiedler op. 144a und das Requiem op. 144b ‘Seele, vergiß sie nicht’, folgten. Laut Auskunft seiner Frau Elsa hatte Max Reger schon 1909 vor dem drohenden "Weltenbrand" gewarnt. Als der Erste Weltkrieg ausbrach, erwies er sich als vehementer Patriot, ersuchte sofort um Einberufung und wurde am 18. August 1914 zu seiner Verbitterung als "total untauglich nach Hause geschickt". Also leistete er seinen Tribut in Form der "dem deutschen Heere" gewidmeten Vaterländischen Ouvertüre op. 140. Am 14. Oktober 1914 schrieb Max Reger an seinen Schüler Hermann Grabner (1886-1969): "Hoffentlich bilden Sie recht viele brave Soldaten für diesen, für unsere Gegner so schmachvollen Krieg aus. Es ist unerhört, mit welcher Niederträchtigkeit und Gemeinheit dieser Krieg von England herbeigeführt und seit langer Zeit vorbereitet worden ist! — Ich arbeite an einem 'Requiem' für Soli, Chor, Orchester und Orgel 'Dem Andenken der in diesem Kriege gefallenen Helden gewidmet!'" Die Witwe berichtet (in Elsa Reger.