Blues with a Feeling." Blues Unlimited, October

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Reveled in the Blues-Rock of Such Groups As the Stones and Cream Were Often Unaware of the Man Responsible for the Songs and Th E Sound

Rock audiences who reveled in the blues-rock of such groups as the Stones and Cream were often unaware of the man responsible for the songs and th e sound. The Poet Laureate of the Blues, he championed the blues and took the first live blues music to Europe. here never was anybody quite like musicians listened to the Chess recordings, adapted the Willie Dixon. The first thing you saw songs to their own high-powered sensibilities, and so when you met him was that huge grin began the blues revival. atop the larger-than-life body; his enor A short list of Willie Dixon’s compositions, and a few mous personal warmth, combined with of the artists who covered them, demonstrates the depth Tan inexhaustible fund of street-smart music business wis and breadth of his musical influence. As a rule the chain dom and a tireless devotion to promoting awareness of the of discovery was: first the song would be recorded by an blues, won him friends and admirers everywhere he went. American blues artist; then, perhaps, an English rock Born in 1915 in Vicksburg, Mississippi, his early ca group would cover that, and then other American blues or reer included a stint with a gospel group; he was already pop artists, hearing the English cover version, would jump writing songs by age sixteen, and would continue to do so behind it T’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man” was written in until at the end of his life he had over 500 compositions 1953 for Muddy Waters, whose version remains the to his credit. -

Golden Gate Grooves, January 2014

Golden Gate Grooves, January 2014 CD REVIEWS Billy Boy Arnold, Charlie Musselwhite, The singers/harmonica players under whose names Remembering Little Walter was issued are an enviable Mark Hummel, Sugar Ray Norcia, James all-star assemblage: Hummel, Harman, Charlie Harman, Remembering Little Walter Musselwhite, Billy Boy Arnold, and Sugar Ray Norcia. Together they make up something like 50% of any by Tom Hyslop reasonable person’s list of the pre-eminent living Latter-day harp men talk harmonica players, and the environment, as one might about Big Walter’s tone, expect, makes for committed and spirited emulate the conversational performances. Sugar Ray’s intense “Mean Old World” is styles of both Sonny Boys, dynamite, as is Musselwhite’s take on the up-tempo admire the power and “One Of These Mornings,” a relative rarity, which also playfulness of Cotton, and features a daredevil guitar break. Tone and dynamics dig Junior Wells’s attitude. are at an impossibly high level throughout—Hummel Some may work on Jimmy and the band dial in a perfect late-night mood on “Blue Reed’s high-end approach, Light,” and the way Harman drives “Crazy Mixed Up or give lip service to Snooky World” hard before breaking it down to a whisper at Pryor or even Louis Myers. But Marion Walter Jacobs the end is masterly. Billy Boy’s “Can’t Hold Out Much was The Man, the player whose stylistic innovations Longer” is splendid on every level. revolutionized the way the instrument was played, and whose technique, taste, and tones continue to baffle That recaps only about half of the program, but the rest and inspire musicians more than 60 years after his of the songs (each performer sings two) are excellent as debut, and nearly 45 years after his untimely death. -

Chicago Blues Guitar

McKinley Morganfield (April 4, 1913 – April 30, 1983), known as Muddy WatersWaters, was an American blues musician, generally considered the Father of modern Chicago blues. Blues musicians Big Bill Morganfield and Larry "Mud Morganfield" Williams are his sons. A major inspiration for the British blues explosion in the 1960s, Muddy was ranked #17 in Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time. Although in his later years Muddy usually said that he was born in Rolling Fork, Mississippi in 1915, he was actually born at Jug's Corner in neighboring Issaquena County, Mississippi in 1913. Recent research has uncovered documentation showing that in the 1930s and 1940s he reported his birth year as 1913 on both his marriage license and musicians' union card. A 1955 interview in the Chicago Defender is the earliest claim of 1915 as his year of birth, which he continued to use in interviews from that point onward. The 1920 census lists him as five years old as of March 6, 1920, suggesting that his birth year may have been 1914. The Social Security Death Index, relying on the Social Security card application submitted after his move to Chicago in the mid '40s, lists him as being born April 4, 1915. His grandmother Della Grant raised him after his mother died shortly after his birth. His fondness for playing in mud earned him the nickname "Muddy" at an early age. He then changed it to "Muddy Water" and finally "Muddy Waters". He started out on harmonica but by age seventeen he was playing the guitar at parties emulating two blues artists who were extremely popular in the south, Son House and Robert Johnson. -

Early Blues Bibliography

EARLY BLUES BIBLIOGRAPHY In any selection of books the choice must inevitably be subjective as to what to include or exclude. This selection has ommitted some choices that other might have included. Also there are many articles, periodicals and magazines that provide information for the researcher that cannot be included here but are, perhaps, in Robert Ford's 'Blues Bibliography' or Edward Komara's '100 Books Every Blues Fan Should Have'. This selection is based very much on my own collection of books found in markets, second hand book shops but more recently through Amazon and the web site 'Abe Books' Many books are out of print, have reached the third, fourth or later edition but details are included here that will allow the collector to locate and purchase their own choice. I have not sought to comment on the accuracy, usefulness or expertise of each publication and care should be taken on choice of purchase as many are price inflated when a little more research will lead to better value for money. Where possible I have tended to provide details of hard cover books but many are also available in soft cover at a much reduced price. It should also be remembered that any list such as this is out of date the moment that it is produced. New books are regularly published. The University Presses of America provide a sound source of academic work under the general priciple of 'Publish or Perish' which reflects the wide range of books from the very simple history to the in depth difficult to read study of an aspect of my favourite genre of music - The Blues. -

August-September 2020

2013 KBA -BLUES SOCIETY OF THE YEAR CELEBRATING OUR 25TH YEAR IN THIS ISSUE: -Consider This- by Lionel Young -The 1960s American Folk Blues Festivals and Manchester Volume 27 No5 August/September Memories -by David Booker 2020 -How To Make a Black Cat Bone - by Rick Saunders Editor- Chick Cavallero -Atlantic City Pop Festival – by Chick Cavallero -Gone But Not Forgotten-Howlin Wolf -by Todd Beebe Consider This -The Forgotten Walter- by Chick Cavallero and bobcorritire.com By Lionel Young -CD Reviews –CBS Members Pages Lionel Young is perhaps the greatest performer in the history of the IBC. He is the CONTRIBUTERS TO THIS ISSUE: only performer to win both the Solo Lionel Young, David Booker, Todd Competition and the Band Competition at the Beebe, Chick Cavallero, Jack Grace, Blues Foundation’s International Blues Dan Willging, Jim O’Neal, Challenge. He did both representing the Bluesoterica.com, Al Chessis, Colorado Blues Society. Racism has our world https://bobcorritore.com, Rick in turmoil and Lionel has witnessed this racism Saunders firsthand. This is Lionel’s story… Sometimes I forget who I am as a person. This exercise helps me to remember some important things about who I am. I believe that this country is changing fast for the long haul. I think in the future, people will look back at this time as pivotal. Please 1 take what’s happening now as an opportunity. This is a time for empathy. Try not to give in to fear and act from it. The disease of racism in this country the United States of America affects me in several ways. -

Beyond 12 Bar Blues Bluesharmonica.Com Support Material Written by David Barrett

Music Theory Study 6 Beyond 12 Bar Blues BluesHarmonica.com Support Material Written by David Barrett Section 1 – Standard 12 Bar Blues Chord Root Notes relative to Home Scale Ex. 1.1 – Standard (Long Changes) I7 IV7 I7 V7 IV7 I7 V7 Example: “Temperature” Tongue Block Study 2 Ex. 1.2 – Quick Change I7 IV7 I7 IV7 I7 V7 IV7 I7 V7 Example: “The Split” Tongue Block Study 4 Section 2 – 12 Bar Blues Variations Ex. 2.1 – 8 Bars of I7 7 i V7 IV7 i7 Example: “Same Thing” by Muddy Waters 1 Ex. 2.2 – Starting on the IV7 IV7 I7 IV7 I7 V7 IV7 I7 Example: “Mystery Train” by Junior Parker (The Paul Butterfield Blues Band 1965 version is a little easier to hear the form than the Junior Parker original) Ex. 2.3 – Stormy Monday Changes (we’ll study this later in the lesson) 7 7 7 I IV I7 ♭II7 I 7 7 IV I ii iii ♭iii 7 7 7 7 7 V ♭VI7 V7 I IV I V Example: “Stormy Monday” Bobby Bland Version Ex. 2.4 – Bar 9 Option (Long V) V7 I7 V7 Example: “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry, Verses (not in the opening chorus if you’re listening to the original track) Ex. 2.5 – Bar 9 Option ii7 V7 I7 Example: “Tell Me What’s the Reason” by T-Bone Walker and “Gary’s Blues” Tongue Block Study 3 (note that the transcription shows it as a V-IV-I, I didn’t want to confuse students at that skill level) Ex. -

Blues Symphony in Atlanta Two Years Ago, Wynton Marsalis Embarked on a New Challenge: Fuse Classical Music with Jazz, Ragtime and Gospel

01_COVER.qxd 12/10/09 11:44 AM Page 1 DOWNBEAT DOWNBEAT BUDDY GUY BUDDY // ERIC BIBB // JOE HENRY JOE HENRY // MYRON WALDEN MYRON WALDEN DownBeat.com $4.99 02 FEBRUARY 2010 FEBRUARY 0 09281 01493 5 FEBRUARY 2010 U.K. £3.50 02-27_FRONT.qxd 12/15/09 1:50 PM Page 2 02-27_FRONT.qxd 12/15/09 1:50 PM Page 3 02-27_FRONT.qxd 12/15/09 1:50 PM Page 4 February 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Contributing Designer Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

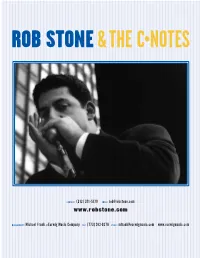

CONTACT: (312) 371 -5179 EMAIL: [email protected]

ROB STONE &THE C•NOTES CONTACT: (312) 371 -5179 EMAIL: [email protected] www.robstone.com MANAGEMENT: Michael Frank AT Earwig Music Company TEL: (773)262-0278 EMAIL: [email protected] www.earwigmusic.com A LIVE PERFORMANCE BY ROB STONE CAN TRANSPORT THE LISTENER BACK TO THE HEYDAY OF CHICAGO BLUES. Fronted by Harp-playing vocalist ROB STONE and held together by a rock-solid rhythm section, the group is comprised of seasoned professionals with well over half a century of combined blues playing experience. They’ve paid their dues in the smoky Chicago blues joints and toured coast to coast across North America and Europe, as well as the Hawaiian islands and Japan, playing countless blues festivals, club dates and television appearances. Separately, the members of the group have recorded for the respected Alligator, Evidence, Hightone, Ice House, Marquis, Appaloosa and Magnum blues labels, and received national recognition in countless blues publications. These musicians have performed with and learned from many of the greats...and it shows from the first note. They are all authentic showmen with pure abil- ity to tear up a stage, as evidenced by their prominent role in the recent Martin Scorsese-produced “Godfathers and Sons” episode of The Blues series that aired recently on PBS stations natiowide. Together they now have a brand new release on Chicago’s Earwig label. As a vocalist Rob Stone is powerful, yet relaxed and natural; as a harmonica player he evokes the sounds of greats like Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson and Walter Horton. This band navigates their way effortlessly through one lean arrangement after another, from a soulful slow blues to a ferocious, driving slide guitar workout recalling past greats like Elmore James, Earl Hooker, and Muddy Waters, as well as all the blues harp legends from the hey- day of Chicago blues. -

LISTENING: ADVANCED LESSONS Lesson 2. Slow Blues 1: Low And

LISTENING: ADVANCED LESSONS Lesson 2. Slow blues 1: Low and Midrange Rhythm Patterns T-Bone Walker “Call It Stormy Monday” BB King “Sweet Little Angel” (Live at the Regal) Albert King “The Sky is Crying,” “Personal Manager” Jimi Hendrix “Red House” Guitar Slim “The Things That I Used to Do” Bobby Bland (Wayne Bennett, gtr) “Stormy Monday Blues” Allman Bros. (Duane Allman, Dickie Betts gtrs) “Stormy Monday” (Live at Fillmore East) 3. Slow blues 2: High-end Rhythm Patterns Same as slow blues 1 4. Slow blues 3: Soloing over Standard Changes BB King “Sweet Little Angel” (Live at the Regal) 5. Slow Blues 4: Chord Variations T-Bone Walker “Call It Stormy Monday” Bobby Bland (Wayne Bennett, gtr) “Stormy Monday Blues” 6. Slow Blues 5: Soloing over Chord Variations Bobby Bland (Wayne Bennett, gtr) “Stormy Monday Blues” Allman Bros. (Duane Allman, Dickie Betts gtrs) “Stormy Monday” (Live at Fillmore East) 7. Super Shuffle 1: Open E T-Bone Walker “T-Bone Shuffle” Jimmy Reed (Eddie Taylor gtr) “High and Lonesome” “Baby What You Want Me to Do” Snooks Eaglin “Sophisticated Blues” Stevie Ray Vaughan “Pride and Joy” 8. Super Shuffle 2: Other Keys Same as Super Shuffle 1 9. Super Shuffle 3: Chicago style Little Walter (Muddy Waters, Jimmy Rogers gtr) “Juke” 10. Chicago-style Melodic Rhythm Jimmy Rogers “That’s All Right,” “Ludella” Little Walter (Louis Myers, Dave Myers gtrs) “Mean Old World” 11. Double-stops 1: Third Intervals Lonnie Johnson “Away Down in the Alley Blues” Robert Johnson “Sweet Home Chicago” Chuck Berry “Thirty Days” Freddie King “The Stumble” Stevie Ray Vaughan “Love Struck Baby,” “Pride & Joy” 12. -

Roots and Branches Handout SESSIONS Revnov20

THE LIVING, BREATHING ART OF MUSIC HISTORY: THE ROOTS AND BRANCHES COURTESY OF WWW.THESESSIONS.ORG COUNTRY: THE ROOTS: The Carter Family/Roy Acuff/Kitty Wells/Hank Williams/Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys BRANCHES: Men: Johnny Cash/George Jones/Waylon Jennings/Conway Twitty/Charlie Pride/The Everly Brothers (see also Rock n’ Roll) WOMEN: Patsy Cline/Loretta Lynn/June Carter/Tammy Wynette/ Dolly Parton INFLUENCED: Jack White, Zac Brown TRIBUTARY: BLUEGRASS : Bill Monroe/Ralph & Carter Stanley/Ricky Scaggs/Allison Krauss TRIBUTARY: COUNTRY ROCK: The Byrds (“Sweetheart Of The Rodeo”)/Poco/early Eagles/Graham Parsons/Emmylou Harris THE BLUES: THE ROOTS (Men): (Delta) Robert Johnson /Son House /Charlie Patton/Mississippi John Hurt/WC Handy/Lonnie Johnson (Chicago) Muddy Waters/Howlin’ Wolf/Little Walter /Buddy Guy/Otis Rush/Elmore James/Jimmy Reed - (Detroit) John Lee Hooker - (Mississippi) BB King/Albert King - (Texas) Freddie King BRANCHES: Stevie Ray Vaughn/Jimi Hendrix/Led Zepplin/ The Fabulous Thunderbirds/Cream/Eric Clapton/early Fleetwood Mac/Allman Brothers/Santana/Paul Butterfield Blues Band MODERN: Robert Cray/Joe Bonamassa/ Warren Haynes/Keb Mo TRIBUTARY- TRANCE BLUES-Oxford MS -Black Possum Records—RL Burnside, Junior Kimbrough (The Black Keys are their disciples) THE BLUES: THE ROOTS (Women): Ma Rainey/Bessie Smith/Sister Rosetta Tharpe (see also “Rock and Roll”) Memphis Minnie (influenced Led Zepplin) BRANCHES (including Jazz) : Billie Holiday/ Dinah Washington/Peggy Lee/Lena Horne/Janis Joplin/Paul Butterfield Blues Band/Michael -

Band/Surname First Name Title Label No

BAND/SURNAME FIRST NAME TITLE LABEL NO DVD 13 Featuring Lester Butler Hightone 115 2000 Lbs Of Blues Soul Of A Sinner Own Label 162 4 Jacks Deal With It Eller Soul 177 44s Americana Rip Cat 173 67 Purple Fishes 67 Purple Fishes Doghowl 173 Abel Bill One-Man Band Own Label 156 Abrahams Mick Live In Madrid Indigo 118 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Swallow 033 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Ace 084 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues/The Good Times Killin' Me Ace 096 Abshire Nathan The Good Times Killin' Me Sonet 044 Ace Black I Am The Boss Card In Your Hand Arhoolie 100 Ace Johnny Memorial Album Ace 063 Aces Aces And Their Guests Storyville 037 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 022 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 033 Aces No One Rides For Free El Toro 163 Aces The Crawl Own Label 177 Acey Johnny My Home Li-Jan 173 Adams Arthur Stomp The Floor Delta Groove 163 Adams Faye I'm Goin' To Leave You Mr R & B 090 Adams Johnny After All The Good Is Gone Ariola 068 Adams Johnny After Dark Rounder 079/080 Adams Johnny Christmas In New Orleans Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny From The Heart Rounder 068 Adams Johnny Heart & Soul Vampi 145 Adams Johnny Heart And Soul SSS 068 Adams Johnny I Won't Cry Rounder 098 Adams Johnny Room With A View Of The Blues Demon 082 Adams Johnny Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me Rounder 097 Adams Johnny Stand By Me Chelsea 068 Adams Johnny The Many Sides Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Sweet Country Voice Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Tan Nighinggale Charly 068 Adams Johnny Walking On A Tightrope Rounder 089 Adamz & Hayes Doug & Dan Blues Duo Blue Skunk Music 166 Adderly & Watts Nat & Noble Noble And Nat Kingsnake 093 Adegbalola Gaye Bitter Sweet Blues Alligator 124 Adler Jimmy Midnight Rooster Bonedog 170 Adler Jimmy Swing It Around Bonedog 158 Agee Ray Black Night is Gone Mr. -

Rambles.Net Review October 2016

Rambles.net Review October 2016 Backtrack Blues Band, Way Back Home (Harpo, 2016) Based in Tampa, formed in 1980, the Backtrack Blues Band takes its name from Little Walter's 1959 instrumental "Back Track." Unlike Walter's classic "Juke," that's one of those numbers not encountered on the usual blues collections. It's mentioned only in passing in Glover/Dirks/Gaines's definitive biography, Blues with a Feeling: The Little Walter Story (2002). To know it, you need to have walked a far piece into the blues weeds. That is where, in fact, you'll find the Backtracks, who practice a form of electric blues that you can't fake. In other words, they will never be mistaken for slumming rockers. These are guys immersed in true blues and seasoned enough to deliver it without frills, albeit with the kinds of chops that come from playing it for a very long time. No, it's not Muddy or Wolf, nor should it be. It is, however, an approach these and other mid-century masters would have appreciated, in other words a thumping, gritty urban sound rooted in the rural Deep South, lots of piercing harmonica (courtesy of Sonny Charles) and the Texas-and-Chicago-style electric lead (Kid Royal), rhythm (Little Johnny Walker), drums (Joe Bencomo) and bass (Stick Davis), with piano (guest Victor Wainwright). None of this would work, naturally, without robust material, which is not a problem on Way Back Home. The originals, from Charles' pen, range from the witty, surely ironically intended "Goin' to Eleuthera" (blues from a Bahamian vacation, not a theme I recall visited in any other blues I've heard; still, a hell of a song) to the politically sharp-edged "Rich Man Blues." There are sure-footed readings of Sonny Boy Williamson II's "Checkin' on My Baby" and "Your Funeral, My Trial." I do wish, though, that more current bands upheld the blues tradition as ably and admirably as the Backtracks do.