Nawab Faizunnesa's Rupjalal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

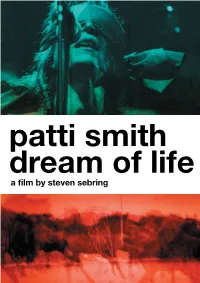

Patti DP.Indd

patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring THIRTEEN/WNET NEW YORK AND CLEAN SOCKS PRESENT PATTI SMITH AND THE BAND: LENNY KAYE OLIVER RAY TONY SHANAHAN JAY DEE DAUGHERTY AND JACKSON SMITH JESSE SMITH DIRECTORS OF TOM VERLAINE SAM SHEPARD PHILIP GLASS BENJAMIN SMOKE FLEA DIRECTOR STEVEN SEBRING PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW SCOTT VOGEL PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP HUNT EXECUTIVE CREATIVE STEVEN SEBRING EDITORS ANGELO CORRAO, A.C.E, LIN POLITO PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW CONSULTANT SHOSHANA SEBRING LINE PRODUCER SONOKO AOYAGI LEOPOLD SUPERVISING INTERNATIONAL PRODUCERS JUNKO TSUNASHIMA KRISTIN LOVEJOY DISTRIBUTION BY CELLULOID DREAMS Thirteen / WNET New York and Clean Socks present Independent Film Competition: Documentary patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring USA - 2008 - Color/B&W - 109 min - 1:66 - Dolby SRD - English www.dreamoflifethemovie.com WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY 2 rue Turgot Sundance office located at the Festival Headquarters 75009 Paris, France Marriott Sidewinder Dr. T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 Jeff Hill – cell: 917-575-8808 [email protected] E: [email protected] www.celluloid-dreams.com Michelle Moretta – cell: 917-749-5578 E: [email protected] synopsis Dream of Life is a plunge into the philosophy and artistry of cult rocker Patti Smith. This portrait of the legendary singer, artist and poet explores themes of spirituality, history and self expression. Known as the godmother of punk, she emerged in the 1970’s, galvanizing the music scene with her unique style of poetic rage, music and trademark swagger. -

History of Medieval Assam Omsons Publications

THE HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL ASSAM ( From the Thirteenth to the Seventeenth century ) A critical and comprehensive history of Assam during the first four centuries of Ahom Rule, based on original Assamese sources, available both in India and England. DR. N.N. ACHARYYA, M.A., PH. D. (LOND.) Reader in History UNIVERSITY OF GAUHATI OMSONS PUBLICATIONS T-7, Rajouri Garden, NEW DELHI-110027 '~istributedby WESTERN BOOK DWT Pan Bazar, Gauhati-78 1001 Assam Reprint : 1992 @ AUTHOR ISBN : 81 -71 17-004-8 (HB) Published by : R. Kumar OMSONS I'UBLICATIONS, T-7,RAJOURl GARDEN NEW DELHI- I 10027. Printed at : EFFICIENT OFFSET PRINTERS 215, Shahrada Bagh Indl. Complex, Phase-11, Phone :533736,533762 Delhi - 11 0035 TO THE SACRED MEMORY OF MY FATHER FOREWORD The state of Assam has certain special features of its own which distinguish it to some extent from the rest of India. One of these features is a tradition of historical writing, such as is not to be found in most parts of the Indian sub-continent. This tradition has left important literary documents in the form of the Buranjis or chronicles, written in simple straightforward prose and recording the historical traditions of the various states and dynasties which ruled Assam before it was incorporated into the domains of the East India Company. These works form an imperishable record of the political history of the region and throw much light also upon the social life of the times. It is probable, though not proven with certainty, that this historical tradition owes its inception to the invasion of the Ahoms, who entered the valley of the Brahmaputra from what is now Burma in 1228, for it is from this momentous year that the Buranji tradition dates. -

Distortion of Indian History for Muslim Appeasement: Part 5A

Voice of India Features Distortion of Indian History for Muslim Appeasement: Part 5a Contributed by Dr. Radhasyam Brahmachari Dr. Radhasyam Brahmachari It is really amazing and ridiculous that, not only the so called pseudo secular and the Marxist historians of India , but also the Western historians portray the Mughal emperor Akbar as a great monarch. But are there sufficient grounds to project him as a great man? The Indian historians, according to the guideline set by the ongoing politics of Muslim appeasement, have to glorify each and every Muslim ruler including Akbar as a compulsion. But it is really incomprehensible why the historians of the West are also in the race in glorifying Akbar, who, in reality, was a foreign invader and came to India to plunder this country. Above all, Akbar possessed three basic Islamic qualities - treachery, lechery and butchery. Akbar, The Great (?) Monarch: It is really amazing and ridiculous that, not only the so called pseudo secular and the Marxist historians of India , but also the Western historians portray the Mughal emperor Akbar as a great monarch. But are there sufficient grounds to project him as a great man? The Indian historians, according to the guideline set by the ongoing politics of Muslim appeasement, have to glorify each and every Muslim ruler including Akbar as a compulsion. But it is really incomprehensible why the historians of the West are also in the race in glorifying Akbar, who, in reality, was a foreign invader and came to India to plunder this country. Above all, Akbar possessed three basic Islamic qualities - treachery, lechery and butchery. -

Annual Report 2011-2012

Annual Report IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 2011-2012 IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) Shri B.N. Srikrishna (w. e. f. 1st January, 2012) Mr. Suresh Kumar Neotia Professor M.G.K. Menon Mr. Rajiv Mehrishi Dr. (Mrs.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. N. N. Vohra Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. Kisan Mehta Mr. Najeeb Jung Dr. (Ms.) Sukrita Paul Kumar Dr. U.D. Choubey Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Lt. Gen. V.R. Raghavan Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mrs. Meera Bhatia Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) Mr. B.N. Srikrishna, Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Chairman Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mr. M. Damodaran Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Lt. Gen. (Retd.) V.R. Raghavan Mr. Jnan Prakash, Chief Finance Officer Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. B. Chakravorty Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms. Premola Ghose, Chief Programme Division Mr. Vijay Kumar Thukral, Executive Chef Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief Maintenance Division Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager (Catering) Ms. Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Ms. Madhu Gupta, Dy. General Manager (Hostel/House Keeping) Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Ms. Seema Kohli, Membership Officer (w. e. f. August 2011) Annual Report 2011-2012 As always, it is a privilege to present the 51th Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing 1 February 2011 and ending 31 January 2012. -

Distortion of Indian History for Muslim Appeasement”, Was Posted on the FFI, a Reader Commented, “Historians Cite Two Historic Rulers of India As ‘The Great’

Distortion of Indian History For Muslim Appeasement Dr. Radhasyam Brahmachari www.faithfreedom.org About the Author Dr Radhasyam Brahmachari, M. Tech, Ph.D., is a scholar of science, who studied at Vidyasagar College, Calcutta, Rama Krishna Mission Residential College, Narandrapur and the University of Calcutta, with unique academic achievement in his credit. He is now serving the Department of Applied Physics, University of Calcutta, as a Professor. Despite being a man of science, he is equally conversant in literary, historical and spiritual spheres, including Vedic philosophy, philosophies other Indian schools and the Western philosophy. At present, he is widely acclaimed as an outstanding authority in comparative studies of religions. He is also a well-known author of a large number of highly thoughtful books that are being appreciated by thinking men and women both in India and abroad. He is also a renowned columnist and his masterly writings frequently appear both in Bengali and English print media. Part 1 The Red Fort in Delhi Whenever we visit the historical monuments of Delhi and Agra, the guides tell us – this is the fort built by Emperor Akbar, or that is the palace built by Emperor Shah Jahan, or here is the minar made by Sultan Qutb- ud-din and so on and so forth. They try to convince us that all the forts, palaces and other monuments of excellent architecture in Delhi and Agra were authored by the Muslim invaders. We also give them a patient hearing and believe in what they say, as our history books also give similar accounts. -

The Myth of Tribal Egalitarianism Under the Lodhis (800-932/1398-1526) Abstract the Afghans Have a Long History in India As Migrants

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 57, Issue No. 1 (January – June, 2020) Fouzia Farooq Ahmed * The Myth of Tribal Egalitarianism Under The Lodhis (800-932/1398-1526) Abstract The Afghans have a long history in India as migrants. Under the Delhi Sultans, they worked as petty soldiers who gradually rose to power and became a strategically placed minority in the power structure. Bahlul Lodhi's ascendancy to the throne of Delhi marked the culmination of Afghan political power in the Delhi Sultanate. It is generally understood that Bahlul Lodhi governed on tribal egalitarian model that was the reason behind the stability and longevity of his reign. His son Sikandar Lodhi maintained a delicate balance between tribal model of governance and kingship. However, Ibrahim Lodhi lost the balance and his attempts for extreme centralization backfired. This article provides a brief history of Afghans as a strategically placed minority in the Delhi Sultanate and argues that Bahlul Lodhi did not aim to establish a tribal egalitarian system. Many of the practices that are associated with him as attempts of introducing egalitarianism were simply efforts not to confront with the already empowered political and military factions. Governance model of Bahlul Lodhi was not a break from the past. Nor was it an Afghan exclusive system. Furthermore, the governance model of Lodhi dynasty had legitimacy issues which were same as his predecessors. Key Words: Tribal Egalitarianism, Afghans in India, tawaif ul Mulukiat By the end of fourteenth century, the political power of the Delhi Sultanate was on a steady decline. -

Iconic Artist

Artist, Musician and Poet Patti Smith’s New Photography and Installation Work to be Presented at the Wadsworth Atheneum HARTFORD, Conn., May 26, 2011 – From her explorations of artistic expression with friend and vanguard photographer Robert Mapplethorpe in the 1960s and 70s to her profound influence on the nascent punk rock scene in the late 1970s and 80s, pioneering artist, musician, and poet Patti Smith has made her mark on the American cultural landscape throughout her 40-year career. This fall, an exhibition of Smith’s work will premiere at the Wadsworth Atheneum, featuring over sixty new photographs and multimedia installations created between 2002 and 2011. The first museum presentation of Smith’s work in the United States in nearly ten years, Patti Smith: Camera Solo will highlight the continual symbiosis between Smith’s photography and her interest in poetry and literature and is on view from October 21, 2011 – February 19, 2012. “Patti Smith’s photography, shaped over decades of observation, commemorates the artists, poets, authors, family and friends from whom she draws inspiration. Modest in scale and shot solely in black and white, they are sometimes disquieting and often beautiful, but always intimate,” said Susan Talbott, Director and CEO, Wadsworth Atheneum. “We are thrilled to present this work at the Wadsworth Atheneum where Smith’s mentor Sam Wagstaff was curator and the work of her dear friend Robert Mapplethorpe was the subject of two separate exhibitions.” Patti Smith: Camera Solo will present approximately sixty black-and-white silver gelatin prints photographed with her vintage Polaroid camera. In the era of digital imaging and manipulation, Smith’s works champion the use of photography in its most classical sense: as a tool to document a “found” moment. -

Le Hurlement Du Papillon Performance Poétique

performance poétique un projet du collectif de création Piment, Langue d’oiseau le hurlement du papillon performance poétique Le hurlement du papillon est une exploration poétique et musicale de l’univers de Patti Smith. Une comédienne, une musicienne et un musicien se proposent de faire découvrir à travers ce spectacle, une des facettes moins connue public francophone de Patti Smith : sa poésie. Le parcours retrace une œuvre littéraire de 1970 à aujourd’hui, dans la pure inspiration de la poésie happening américaine, mouvement initié dans les années soixante par des personnalités telles que John Giorno, William Burroughs, Alan Ginsberg, Brion Gysin... Photo Robert Mappelthorpe (1974) Comme elle a souvent l’habitude de le faire lors de ses récitals poétiques, ses poèmes, ici dits en français, seront accompagnés d’univers sonores et musicaux originaux, joués en direct par les musiciens. Le hurlement du papillon est aussi un voyage survolant sa carrière musicale par la reprise d’une chanson de chacun de ses albums de « Horses » (1975) à « Trampin’ » (2004). Le parti pris de sobriété de sa forme en fait un spectacle s’adaptant aussi bien aux théâtres ou aux festivals de rue, ainsi qu’aux petits lieux insolites. Photo Annie Leibowitz (1995) Poète, auteur, compositeur, photographe, peintre, Patti Smith, née en 1946 est une artiste, un esprit libre qui fascine par la multiplicité de ses moyens d’expression, par la pureté de son parcours artistique sans concession. Ainsi traverse t’elle les courants, les modes et donc le temps. Les poèmes interprétés dont « le hurlement du papillon » seront choisis dans les deux recueils parus aux éditions Tristram : « La mer de corail » & « Corps de plane » qui regroupent des textes parus entre 1970 & 1979 ; ouvrages édités en France en 1996 & 1998. -

Patti Smith: Dream of Life” Presents Evocative Portrait of the Legendary Rocker and Artist, Wednesday, Dec

For Immediate Release Contacts: POV Communications: 212-989-7425. Emergency contact: 646-729-4748 Cynthia López, [email protected], Cathy Fisher, [email protected] PBS PressRoom: pressroom.pbs.org/programs/p.o.v. POV online pressroom: www.pbs.org/pov/pressroom “Patti Smith: Dream of Life” Presents Evocative Portrait of the Legendary Rocker and Artist, Wednesday, Dec. 30, 2009, at 9 p.m. in Special Presentation on PBS’ POV Smith was both participant and witness to a seminal scene in American culture; film portrays her friendships and work with Robert Mapplethorpe, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Sam Shepard and Bob Dylan “Created over a heroic 11 years … a lovely … first feature. … Mr. Sebring creates a structure for the film in which past and present seem to flow effortlessly and ceaselessly into each other.” — Manohla Dargis, The New York Times Shot over 11 years by acclaimed fashion photographer Steven Sebring, “Patti Smith: Dream of Life” is a remarkable plunge into the life, art, memories and philosophical reflections of the legendary rocker, poet and artist. Sometimes dubbed the “godmother of punk” — a designation justified by clips of her early rage-fueled performances — Smith was much more than that when she broke through with her 1975 debut album, Horses. A poet and visual artist as well as a rocker, she befriended and collaborated with some of the brightest lights of the American counterculture, an often testosterone-driven scene to which she brought a swagger and fierceness all her own. In “Patti Smith: Dream of Life,” the artist’s memories of these times, and of a period of domestic happiness and the tragedies that brought her back to the stage, attain an intense, hypnotic lyricism, much like that of her own songs. -

![Struggle for Empire-Afghans, Rajputs and the Mughals]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3020/struggle-for-empire-afghans-rajputs-and-the-mughals-2723020.webp)

Struggle for Empire-Afghans, Rajputs and the Mughals]

TABLE OF CONTENTS TOPIC PAGE NO. UNIT-I [The age of conflict and the Turkish conquest of North India] West and Central Asia between the 10th and 12th centuries 01 Developments in West and Central Asia 01 The Turkish advance towards India: The Hindushahis 03 Rajput Kingdoms in North India and the Ghaznavids 04 The Rise of Ghurids and their advance into India 06 The Battles of Tarain 07 Turkish Expansion into the Upper Ganga Valley 08 Muizzuddin Muhammad and Mahmud Ghazni 09 Causes of the defeat of the Rajputs 10 UNIT-II [Establishment of the Delhi Sultanate (1206-1236)] Establishment & territorial consolidation (1206-1236) 13 Qutbuddin Aibak and Iltutmish 14 Punjab and Sindh 15 Turkish Conquest of Bihar and Lakhnauti 15 Relations of Bengal with Delhi 17 Internal Rebellions, Conquest of Ranthambhor and Gwaliyar, and Raids into Bundelkhand and Malwa 17 Estimate of Iltutmish as a Ruler 18 UNIT-III [Struggle for the Establishment of a Centralized Monarchy (1236-1290)] Razia and the Period of Instability (1236-46) 19 The Age of Balban (1246-87) 21 Struggle for the Territorial Integrity of the Sultanate 25 Assessment of Balban 27 UNIT-IV [The Mongol threat to India during the 13th and 14th centuries] The Mongol Incursions (upto 1292) 29 The Mongol Threat to Delhi (1292-1328) 31 UNIT-V [Internal Restructuring of the Delhi Sultanate (1290-1320)] Jalaluddin and Alauddin Khalji's Approaches to the State 35 Agrarian and Market Reforms of Alauddin 36 The Territorial Expansion of the Delhi Sultanate (upto 1328) 41 ~ i ~ UNIT-VI -

Acacia Fall 2020 Rights List

Acacia Acacia House House Catalogue Summer Fall - 2020Fall 2019 Catalogue 1 Dear Reader, We invite you to look at our Fall 2020 International Rights Catalogue, a list that includes works by adult authors represented by Acacia House, but also recent and forthcoming titles from: Douglas & McIntyre; Fifth House; Fitzhenry & Whiteside; Harbour Publishing; Lilygrove; NeWest Press; New Star Books; Shillingstone: Véhicule; West End Books; Whitecap Books and Words Indeed whom we represent for rights sales. We hope you enjoy reading through our catalogue. If you would like further information on any title(s),we can be reached by phone at (519) 752-0978 or by e-mail: [email protected] — or you can contact our co-agents who handle rights for us in the following languages and countries: Bill Hanna Photo© Frank Olenski Brazilian: Dominique Makins, DMM Literary Management Chinese: Wendy King, Big AppleTuttle-Mori Agency Serbo Croatian: Reka Bartha Katai & Bolza Literary Agency Dutch: Linda Kohn, Internationaal Literatuur Bureau German: Peter Fritz, Christian Dittus, Antonia Fritz, Paul & Peter Fritz Agency Greek: Nike Davarinou, Read ’n Right Agency Hungarian: Lekli Mikii, Katai & Bolza Literary Agency Indonesia: Santo Manurung, Maxima Creative Agency Israel: Geula Guerts, The Deborah Harris Agency Italian: Daniela Micura, Daniela Micura Literary Agency Japanese: Miko Yamanouchi, Japan UNI Agency Korean: Duran Kim, Duran Kim Literary Agency Malaysia: Wendy King, Big AppleTuttle-Mori Agency Polish: Maria Strarz-Kanska, Graal Ltd. Portugal: Anna Bofill, Carmen Balcells S.A Kathy Olenski Photo☺ Frank Olenski Romanian: Simona Kessler, Simona Kessler Agency Russian: Alexander Korzhenevsky, Alexander Korzhenevski Table of Contents Agency Fiction 3 South Africa: TerryTemple, International Press Agency Historical Fiction 21 Scandinavia: Anette Nicolaissen, A. -

Patti Smith, Polar Music Prize Laureate 2011 Patti Smith, Born In

Patti Smith, Polar Music Prize Laureate 2011 Patti Smith, born in Chicago in 1946, the oldest of four siblings, was raised in South Jersey. From an early age she gravitated toward the arts and human rights issues. She studied at Glassboro State Teachers College and migrated to New York City in 1967. She teamed up with art student Robert Mapplethorpe and the two encouraged each other’s work process, both of them pursuing painting and drawing and she poetry. In February 1971 Smith performed her first public reading at St. Mark’s Church on the lower eastside, accompanied by Lenny Kaye on guitar. In April of the same year she co-wrote and performed the play Cowboy Mouth with playwright Sam Shepard. Continuing to write and perform her poetry, in 1974 Smith and Lenny Kaye added Richard Sohl on piano. As a trio they played regularly around New York, including the legendary Max’s Kansas City, centering on their collective and varied musical roots and her improvised poetry. The independent single release, Hey Joe/Piss Factory, featured Tom Verlaine. Along with the highly innovative and influential group Television, the trio helped to open up a restricted music scene that centered at CBGBs in New York City. After recruiting guitarist Ivan Kral, they played CBGBs for eight weeks in the Spring of 1975 and then added drummer Jay Dee Daugherty. Smith described their work as “three chords merged with the power of the word.” Smith was signed by Clive Davis to his fledgling Arista label and recorded four albums: Horses (produced by John Cale), Radio Ethiopia (produced by Jack Douglas), Easter (produced by Jimmy Iovine), which included her top twenty hit Because the Night, co-written with Bruce Springsteen, and Wave (produced by Todd Rundgren).