The Monastery Rules: Buddhist Monastic Organization in Pre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2018-Summer 2019

# 29 – Summer 2018-Summer 2019 H.H. Lungtok Dawa Dhargyal Rinpoche Enthusiasm in Our Dharma Family CyberSangha Dying with Confidence LIGMINCHA EUROPE MAGAZINE 2019/29 — CONTENTS GREETINGS 3 Greetings and news from the editors IN THE SPOTLIGHT 4 Five Extraordinary Days at Menri Monastery GOING BEYOND 8 Retreat Program 2019/2020 at Lishu Institute THE SANGHA 9 There Is Much Enthusiasm and Excitement in Our Dharma Family 14 Introducing CyberSangha 15 What's Been Happening in Europe 27 Meditations to Manifest your Positive Qualities 28 Entering into the Light ART IN THE SANGHA 29 Yungdrun Bön Calendar for 2020 30 Powa Retreat, Fall 2018 PREPARING TO DIE 31 Dying with Confidence THE TEACHER AND THE DHARMA 33 Bringing the Bon Teachings into the World 40 Tibetan Yoga for Health & Well-Being 44 Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche's 2019 European Seminars and online Teachings THE LIGMINCHA EUROPE MAGAZINE is a joint venture of the community of European students of Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche. Ideas and contributions are welcome at [email protected]. You can find this and the previous issues at www.ligmincha.eu, and you can find us on the Facebook page of Ligmincha Europe Magazine. Chief editor: Ton Bisscheroux Editors: Jantien Spindler and Regula Franz Editorial assistance: Michaela Clarke and Vickie Walter Proofreaders: Bob Anger, Dana Lloyd Thomas and Lise Brenner Technical assistance: Ligmincha.eu Webmaster Expert Circle Cover layout: Nathalie Arts page Contents 2 GREETINGS AND NEWS FROM THE EDITORS Dear Readers, Dear Practitioners of Bon, It's been a year since we published our last This issue also contains an interview with Rob magazine. -

'A Unique View from Within'

Orientations | Volume 47 Number 7 | OCTOBER 2016 ‘projects in progress’ at the time of his death in 1999. (Fig. 1; see also Fig. 5). The sixth picture-map shows In my research, I use the Wise Collection as a case a 1.9-metre-long panorama of the Zangskar valley. study to examine the processes by which knowledge In addition, there are 28 related drawings showing of Tibet was acquired, collected and represented detailed illustrations of selected monasteries, and the intentions and motivations behind these monastic rituals, wedding ceremonies and so on. ‘A Unique View from Within’: processes. With the forthcoming publication of the Places on the panoramic map are consecutively whole collection and the results of my research numbered from Lhasa westwards and southwards (Lange, forthcoming), I intend to draw attention to in Arabic numerals. Tibetan numerals can be found The Representation of Tibetan Architecture this neglected material and its historical significance. mainly on the backs of the drawings, marking the In this essay I will give a general overview of the order of the sheets. Altogether there are more than in the British Library’s Wise Collection collection and discuss the unique style of the 900 numbered annotations on the Wise Collection drawings. Using examples of selected illustrations drawings. Explanatory notes referring to these of towns and monasteries, I will show how Tibetan numbers were written in English on separate sheets Diana Lange monastic architecture was embedded in picture- of paper. Some drawings bear additional labels in maps and represented in detail. Tibetan and English, while others are accompanied The Wise Collection comprises six large picture- neither by captions nor by explanatory texts. -

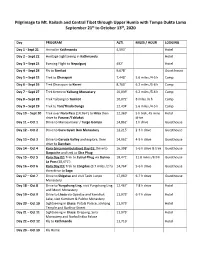

Pilgrimage to Mt. Kailash and Central Tibet Through Upper Humla with Tempa Dukte Lama September 21St to October 13Th, 2020

Pilgrimage to Mt. Kailash and Central Tibet through Upper Humla with Tempa Dukte Lama September 21st to October 13th, 2020 Day PROGRAM ALTI. MILES / HOUR LODGING Day 1 - Sept 21 Arrival in Kathmandu 4,593’ Hotel Day 2 – Sept 22 Heritage Sightseeing in Kathmandu Hotel Day 3 – Sept 23 Evening Flight to Nepalgunj 492’ Hotel Day 4 – Sept 24 Fly to Simikot 9,678’ Guest house Day 5 – Sept 25 Trek to Dharapari 7,448’ 5.6 miles /4-5 h Camp Day 6 – Sept 26 Trek Dharapori to Kermi 8,760’ 6.2 miles /5-6 h Camp Day 7 – Sept 27 Trek Kermi to Yalbang Monastery 10,039’ 6.2 miles /5-6 h Camp Day 8 – Sept 28 Trek Yalbang to Tumkot 10,072’ 8 miles /6 h Camp Day 9 – Sept 29 Trek to Yari/Thado Dunga 12,434’ 5.6 miles /4-5 h Camp Day 10 – Sept 30 Trek over Nara Pass (14,764’) to Hilsa then 12,369’ 5 h trek, 45 mins Hotel drive to Purang /Taklakot drive Day 11 – Oct 1 Drive to Manasarowar / Turgo Gompa 14,862’ 1 h drive Guesthouse Day 12 – Oct 2 Drive to Guru Gyam Bon Monastery 12,215’ 2-3 h drive Guesthouse Day 13 – Oct 3 Drive to Garuda Valley and explore, then 14,961’ 4-5 h drive Guesthouse drive to Darchen Day 14 – Oct 4 Kora (circumambulation) Day 01: Drive to 16,398’ 5-6 h drive & trek Guesthouse Darpoche and trek to Dira Phug Day 15 – Oct 5 Kora Day 02: Trek to Zutrul Phug via Dolma 18,471’ 11.8 miles /8-9 h Guesthouse La Pass (18,471’) Day 16 – Oct 6 Kora Day 03: Trek to Zongdue (3.7 miles /2 h) 14,764’ 5-6 h drive Guesthouse then drive to Saga Day 17 – Oct 7 Drive to Shigatse and visit Tashi Lunpo 17,060’ 6-7 h drive Guesthouse Monastery Day 18 – Oct 8 Drive to Yungdrung Ling, visit Yungdrung Ling 12,467’ 7-8 h drive Hotel and Menri Monastery Day 19 – Oct 9 Drive to Lhasa via Gyantse and Yamdrok 11,975’ 6-7 h drive Hotel Lake, visit Kumbum & Palcho Monastery Day 20 – Oct 10 Sightseeing in Lhasa: Potala Palace, Jokhang 11,975’ Hotel Temple and Barkhor Street Day 21 – Oct 11 Sightseeing in Lhasa: Drepung, Sera 11,975’ Hotel Monastery and Norbulinkha Palace Day 22 – Oct 12 Fly to Kathmandu 11,716’ Hotel Day 23 – Oct 13 Fly Home . -

Interview #27C – Jigdal Dagchen Sakya, His Holiness November 15, 2014

Tibet Oral History Project Interview #27C – Jigdal Dagchen Sakya, His Holiness November 15, 2014 The Tibet Oral History Project serves as a repository for the memories, testimonies and opinions of elderly Tibetan refugees. The oral history process records the words spoken by interviewees in response to questions from an interviewer. The interviewees’ statements should not be considered verified or complete accounts of events and the Tibet Oral History Project expressly disclaims any liability for the inaccuracy of any information provided by the interviewees. The interviewees’ statements do not necessarily represent the views of the Tibet Oral History Project or any of its officers, contractors or volunteers. This translation and transcript is provided for individual research purposes only. For all other uses, including publication, reproduction and quotation beyond fair use, permission must be obtained in writing from: Tibet Oral History Project, P.O. Box 6464, Moraga, CA 94570-6464, United States. Copyright © 2015 Tibet Oral History Project. TIBET ORAL HISTORY PROJECT www.TibetOralHistory.org INTERVIEW SUMMARY SHEET 1. Interview Number: #27C 2. Interviewee: Jigdal Dagchen Sakya, His Holiness 3. Age: 85 4. Date of Birth: 1929 5. Sex: Male 6. Birthplace: Sakya 7. Province: Utsang 8. Year of leaving Tibet: 1959 9. Date of Interview: November 15, 2014 10. Place of Interview: Sakya Monastery, Seattle, Washington, USA 11. Length of Interview: 1 hr 19 min 12. Interviewer: Marcella Adamski 13. Interpreter: Jamyang D. Sakya 14. Videographer: Tony Sondag 15. Translator: Tenzin Yangchen Biographical Information: His Holiness Jigdal Dagchen Sakya was born in the town of Sakya in Utsang Province. He is a descendant of the Khon lineage called the Phuntsok Phodrang. -

Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia 12-2.Indd

Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 5/2 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 1 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 2 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 Ethnolinguistics, Sociolinguistics, Religion and Culture Volume 5, No. 2 Publication of Charles University in Prague Philosophical Faculty, Institute of South and Central Asia Seminar of Mongolian Studies Prague 2012 ISSN 1803–5647 MMongolo-Tibeticaongolo-Tibetica PPragensiaragensia 112-2.indd2-2.indd 3 115.5. 22.. 22013013 119:13:299:13:29 Th is journal is published as a part of the Programme for the Development of Fields of Study at Charles University, Oriental and African Studies, sub-programme “Th e process of transformation in the language and cultural diff erentness of the countries of South and Central Asia”, a project of the Philosophical Faculty, Charles University in Prague. Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia ’12 Linguistics, Ethnolinguistics, Religion and Culture Volume 5, No. 2 (2012) © Editors Editors-in-chief: Jaroslav Vacek and Alena Oberfalzerová Editorial Board: Daniel Berounský (Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic) Agata Bareja-Starzyńska (University of Warsaw, Poland) Katia Buff etrille (École pratique des Hautes-Études, Paris, France) J. Lubsangdorji (Charles University Prague, Czech Republic) Marie-Dominique Even (Centre National des Recherches Scientifi ques, Paris, France) Marek Mejor (University of Warsaw, Poland) Tsevel Shagdarsurung (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) Domiin Tömörtogoo (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) Reviewed by Prof. Václav Blažek (Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic) and Prof. Tsevel Shagdarsurung (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) English correction: Dr. -

Membership at Sakya Monastery 25 Email: [email protected] Tara Meditation Center on Whidbey Island 27 Website

p~âó~=jçå~ëíÉêó=çÑ=qáÄÉí~å=_ìÇÇÜáëã= Introductory Guide Through the practice of Vajrayana Buddhism, may the flower of Tibetan culture be preserved for the benefit all beings. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Background on H.H. Jigdal Dagchen Sakya 6 Short Overview of Tibetan Buddhism 9 Guide to the Main Shrine Room 13 Becoming a Buddhist 17 p~âó~=jçå~ëíÉêó=çÑp~âó~=jçå~ëíÉêó=çÑ==== qáÄÉí~å=_ìÇÇÜáëã Meditation Practices at Sakya Monastery 19 Special Tibetan Buddhist Ceremonies 22 Address: 108 NW 83rd Street Virupa Educational Institute 23 Seattle, WA 98117 Children’s Dharma School 24 Tel: 206.789.2578 (Open Mondays - Fridays, 8:00 am - noon) Membership at Sakya Monastery 25 Email: [email protected] Tara Meditation Center on Whidbey Island 27 Website: www.sakya.org © 2010 Sakya Monastery of Tibetan MESSAGE FROM THE CO-DIRECTORS Buddhism, All rights reserved. Welcome to Sakya Monastery! One of the key goals of Sakya Monastery is to provide access to the Buddha’s teachings to enable people to develop their inner spiritual qualities and progress to enlightenment step by step. When people first come to Sakya Monastery, they have lots of questions about Tibetan Buddhism, our Lamas, Sakya Monas- tery and the spiritual practices we do here, and how to act when attending one of our meditations. This booklet has been created to answer many of those questions so that you will be comfortable and feel welcomed whenever you visit Sakya Monastery. We look forward to seeing you soon and often! Adrienne Chan & Chuck Pettis Co-Executive Directors Ntu Ntu PURPOSE Introduction The purpose of Sakya Monastery Sakya Monastery provides access to the Buddha’s teachings and is to share and preserve Tibetan guidance in a community of practitioners. -

Tibetan Nuns Debate for Dalai Lama

PO Box 6483, Ithaca, NY 14851 607-273-8519 WINTER 1996 Newsletter and Catalog Supplement Tibetan Nuns Debate for Dalai Lama NAMGYAL INSTITUTE by Thubten Chodron I began hearing rumors the At 4PM nuns, monks, and Enters New Phase morning of Sunday, October 8th laypeople gathered in the court- that nuns were going to debate in yard. The nuns were already debat- the courtyard in front of the main ing on one side, and their voices of Development temple in Dharamsala and that His and clapping hands, a mark of de- Holiness the Dalai Lama was to be bate as done in Tibetan Buddhism, Spring 1996 will mark the end Lama. The monks have received a • Obtain health insurance for the there to observe. There were many filled the place. Suddenly there was of the fourth full year of operation wide and popular reception Namgyal monks, none of whom nuns in McLeod Gam' at the time; a hush and the nuns who had been and the beginning of a new phase throughout the U.S. and Canada, currently have health insurance. the major nunneries in India and debating went onto the stage in the of development for the Institute of and there is an ever-growing circle • Fund a full-time paid adminis- Nepal were having their first ever "pavilion" where His Holiness' seat Buddhist Studies established by of students at the Institute in trator. Our two administrators inter-nunnery debate. The fact that was. His Holiness soon came out, Namgyal Monastery in North Ithaca, confirming the validity of have each put in forty hours per the best nun debaters had^athered the nuns prostrated and were America. -

The Journal of the International Association for Bon Research

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR BON RESEARCH ✴ LA REVUE DE L’ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE POUR LA RECHERCHE SUR LE BÖN New Horizons in Bon Studies 3 Inaugural Issue Volume 1 – Issue 1 The International Association for Bon Research L’association pour la recherche sur le Bön c/o Dr J.F. Marc des Jardins Department of Religion, Concordia University 1455 de Maisonneuve Ouest, R205 Montreal, Quebec H3G 1M8 Logo: “Gshen rab mi bo descending to Earth as a Coucou bird” by Agnieszka Helman-Wazny Copyright © 2013 The International Association for Bon Research ISSN: 2291-8663 THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR BON RESEARCH – LA REVUE DE L’ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE POUR LA RECHERCHE SUR LE BÖN (JIABR-RAIRB) Inaugural Issue – Première parution December 2013 – Décembre 2013 Chief editor: J.F. Marc des Jardins Editor of this issue: Nathan W. Hill Editorial Board: Samten G. Karmay (CNRS); Nathan Hill (SOAS); Charles Ramble (EPHE, CNRS); Tsering Thar (Minzu University of China); J.F. Marc des Jardins (Concordia). Introduction: The JIABR – RAIBR is the yearly publication of the International Association for Bon Research. The IABR is a non-profit organisation registered under the Federal Canadian Registrar (DATE). IABR - AIRB is an association dedicated to the study and the promotion of research on the Tibetan Bön religion. It is an association of dedicated researchers who engage in the critical analysis and research on Bön according to commonly accepted scientific criteria in scientific institutes. The fields of studies represented by our members encompass the different academic disciplines found in Humanities, Social Sciences and other connected specialities. -

The Voice of Clear Light

, The Voice of Clear Light • Ligmincha Institute Newsletter • Volume 1, No. 1 • Summer 1992 SEAL OF THE INSTITUTE The Institute is named for the Ligmin- cha dynasty of kings of the ancient country of Zhang-Zhung in Western Tibet. The inscription around the out- ermost circle is written in Zhang Zhung letters which originally appeared on the official seal belonging to the last king of Zhang Zhung. It means "The king of existence who has power over all." Written in Tibetan, it is Kha mTshan pa shang lig zhi ra rtsa. Within the next circle are found the five petals of a lotus flower, symbolizing the five sciences (rig-gnas lnga) necessary for the edu- cated human being to live fully in the world. Inside this circle of general hu- John Reynolds, Arthur Mandlebaum, Walter Coppedge, and several man knowledge is another circle con- university students. Lar and Paige Short from Grace Essence Fellow- taining an eight-pointed star. This sig- ship traveled from Albuquerque, New Mexico to attend the retreat, as nifies the first eight ways toward en- did a student of theirs. Retreatants came from the West coast, Texas, lightenment among the Causal and New Mexico, and many from the East coast. The weather was Fruitional Vehicles of the Nine Ways of beautiful, unseasonably mild for Virginia in the summer, so we were Bon. At the center of the seal is the all very comfortable when we packed into the shrine room for teachings Tibetan letter, ,-(Ah) which represents and practices. Everyone noticed the changes at Ligmincha since the the Ninth Way, the ultimate Path of last retreat at the end of March. -

Films and Videos on Tibet

FILMS AND VIDEOS ON TIBET Last updated: 15 July 2012 This list is maintained by A. Tom Grunfeld ( [email protected] ). It was begun many years ago (in the early 1990s?) by Sonam Dargyay and others have contributed since. I welcome - and encourage - any contributions of ideas, suggestions for changes, corrections and, of course, additions. All the information I have available to me is on this list so please do not ask if I have any additional information because I don't. I have seen only a few of the films on this list and, therefore, cannot vouch for everything that is said about them. Whenever possible I have listed the source of the information. I will update this list as I receive additional information so checking it periodically would be prudent. This list has no copyright; I gladly share it with whomever wants to use it. I would appreciate, however, an acknowledgment when the list, or any part, of it is used. The following represents a resource list of films and videos on Tibet. For more information about acquiring these films, contact the distributors directly. Office of Tibet, 241 E. 32nd Street, New York, NY 10016 (212-213-5010) Wisdom Films (Wisdom Publications no longer sells these films. If anyone knows the address of the company that now sells these films, or how to get in touch with them, I would appreciate it if you could let me know. Many, but not all, of their films are sold by Meridian Trust.) Meridian Trust, 330 Harrow Road, London W9 2HP (01-289-5443)http://www.meridian-trust/.org Mystic Fire Videos, P.O. -

Establishing Lineage Legitimacy and Building Labrang Monastery As “The Source of Dharma”: Jikmed Wangpo (1728–1791) Taking the Helm

religions Article Establishing Lineage Legitimacy and Building Labrang Monastery as “the Source of Dharma”: Jikmed Wangpo (1728–1791) Taking the Helm Rinchen Dorje The Center for Research on Ethnic Minorities in Northwest China, The College of History and Culture, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] Abstract: The eighteenth century witnessed the continuity of Geluk growth in Amdo from the preceding century. Geluk inspiration and legacy from Central Tibet and the accompanying political patronage emanating from the Manchus, Mongols, and local Tibetans figured prominently as the engine behind the Geluk influence that swept Amdo. The Geluk rise in the region resulted from contributions made by native Geluk Buddhists. Amdo native monks are, however, rarely treated with as much attention as they deserve for cultivating extensive networks of intellectual transmission, reorienting and shaping the school’s future. I therefore propose that we approach Geluk hegemony and their broad initiatives in the region with respect to the school’s intellectual and cultural order and native Amdo Buddhist monks’ role in shaping Geluk history in Amdo and beyond in Tibet. Such a focus highlights their impact in shaping the trajectory of Geluk history in Tibet and Amdo in particular. The historical and biographical literature dealing with the life of Jikmed Wangpo affords us a rare window into the pivotal time when every effort was made to cultivate a vast network of institutions and masters across Tibet. This further spurred an institutional growth of Citation: Dorje, Rinchen. 2021. Buddhist transmission, constructing authenticity and authority thereof, as they were closely tied to Establishing Lineage Legitimacy and reincarnation lineage, intellectual traditions, and monastic institutions. -

VEI Catalog Summer 2019.Pub

Summer 2019 at Sakya Monastery of Tibetan Buddhism 108 NW 83rd Street Seattle, WA 98117 Tel: 206.789.2573 Website: www.sakya.org Email: [email protected] In this quarter’s catalog: Prayer, Faith & Devotion A teaching by H.H. Jigdal Dagchen Dorje Chang, “Three Types of Faith and Connection to the Guru” 3rd Annual North American Sakya World Peace Monlam Tsuktor Barwa Initiation Saka Dawa Retreat Guru Rinpoche Bumtsok Special Teaching on the Aspiration of Samantabhadra by Geshe Jamyang Tsultrim Fifty Verses of Guru Devotion Setting Up a Home Shrine And more! The Marici Fellowship: The Marici Fellowship Summer Camp - not to be missed! Monthly Meal Service Speaker Series Young Sakya Monk in Lumbini 2010. Photo by Teresa Lamb. What Sakya Monastery Offers From the foundation laid by His Holiness Jigdal Dagchen Sakya Dorje Chang (1929 - 2016), it is the aspiration of our Head Lama, His Eminence Avikrita Vajra Rinpoche, that Sakya Monastery continues to provide multiple pathways for all who are interested in studying the Buddhadharma. In honor of the Sakya World Peace Monlam, we focus on prayer, faith and devotion for this quarter. We have included a special teaching by H.H. Jigdal Dagchen Dorje Chang the founder of Sakya Monastery, Seattle. For those new to Sakya Monastery, you can find out about all our regular activities and practices through our Sunday morning introductory classes. These are listed under Welcome to Buddhism at Sakya Monastery. Special Ceremonies and Events shows empowerments, retreats and special rituals. Dharma classes and teachings are listed under Explorations in Dharma. Small group Study Intensives will continue in the Fall Quarter.