The Last Norseman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TT Skye Summer from 25Th May 2015.Indd

n Portree Fiscavaig Broadford Elgol Armadale Kyleakin Kyle Of Lochalsh Dunvegan Uig Flodigarry Staffi Includes School buses in Skye Skye 51 52 54 55 56 57A 57C 58 59 152 155 158 164 60X times bus Information correct at time of print of time at correct Information From 25 May 2015 May 25 From Armadale Broadford Kyle of Lochalsh 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 Service No. 51 51 51A 51 51 NSch NSch NSch School Armadale Pier - - - - - 1430 - - Armadale Pier - - 1430 - - Holidays Only Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - - - - 1438 - - Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - 1433 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - - - - 1446 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - 1441 - - Drumfearn Road End - - - - - 1451 - - Drumfearn Road End - - 1446 - - Broadford Hospital Road End 0815 0940 1045 1210 1343 1625 1750 Broadford Hospital Road End 0940 1343 1625 1750 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0830 0955 1100 1225 1358 1509 1640 1805 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0955 1358 1504 1640 1805 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0835 1000 1105 1230 1403 1514 1645 1810 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 1000 1403 1509 1645 1810 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle of Lochalsh Broadford Armadale 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 51 Service No. 51 51A 51 51 51 NSch NSch NSch NSch School Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0740 0850 1015 1138 1338 1405 1600 1720 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0910 1341 1405 1600 1720 Holidays Only Kyleakin Youth -

THE ISLE of SKYE in the OLDEN TIMES. by the Rev

THE ISLE OF SKYE IN THE OLDEN TIMES. By the Rev. ALEX. MACGREGOR, M.A. OF late years, and even this present season, much has been written about this tourists and others interesting Island by ; con- yet there are many relics, legends, and subjects of folk-lore " " nected with the far-famed Isle of Mist which have not as yet been fully developed. Such learned and enthusiastic gentle- men as the late Alexander Smith, Sheriff Nicolson of of the Kirkcudbright, and others, have given vivid descriptions unrivalled of this still much scenery remarkable island ; yet remains to be explored and detailed as to the origin, history, and antiquity of the numberless duns or forts which once surrounded and protected it. With each and all of these romantic that places of defence there is a history connected, and where is not is history reliable and confirmed by facts, the blank amply from supplied by fanciful but interesting legends, handed down ancient days by tradition, and fostered by the natural feelings and superstitious beliefs of the natives " " How well if the talented Nether-Lochaber were located even for a in the month this interesting isle, to enjoy pure hospitality and friendship of its proverbially kind inhabitants. well were and How. he to roam freely amid its peaked mountains shaded valleys, to visit its dims and strongholds, and its varie- gated natural curiosities, and withal to make his magic pen bear upon its archaeological stores and its numberless specimens of interesting folk-lore. My learned friend would feel no ordinary interest in handling, if not in wrapping himself in, the Fairy Flag preserved in Dunvegan Castle. -

Section 1 Section 0

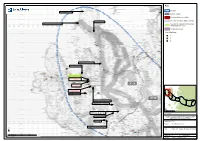

Key Corridor Dun Borrafiach Broch SM Section Divider Scheduled Monument (SM) Inventory of Historic Battlefields Site Dun Hallin Broch SM Trumpan Church and Burial Ground SM Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes Site (GDL) Conservation Area Listed Buildings ! A ! B ! C 0C - Greshornish 0A - Existing 0B - Garradh Mor Annait Monastic Settlement SM Dun Fiadhairt Broch SM Dunvegan Castle GDL Duirinish Parish Church A Listed Building Section 0 Dunvegan Castle A Listed Building Duirinish Parish Church A Listed Building Dun Osdale Broch SM 0E - Ben Aketil Section 1 St Mary's Church and Burial Ground Barpannan Chambered Cairns SM 0D - Existing ¯ 0 5 10 20 30 40 Kilometers Abhainn Bhaile Mheadhonaich Broch and Standing Stone SM Location Plan Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. Dun Feorlig, Broch SM Crown copyright and database right 2020 all rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number EL273236. Dun Neill SM Project No: LT91 Project: Skye Reinforcement Ardmore Chapel and Burial Ground SM ¯ Title: Figure 5.0 - Cultural Heritage (Section 0) 0 0.75 1.5 3 4.5 6 Kilometers Scale - 1:100,000 Drawn by: LT Date: 05/03/2020 Drawing: 119026-D-CH5.0-1.0.0 Key Corridor Section Divider Route Options Clach Ard Symbol Stone SM Scheduled Monument (SM) Skeabost Island, St Columba's Church SM Inventory of Historic Battlefields Site Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes Site (GDL) Conservation Area Listed Buildings ! A ! B ! C Section 0 Dun Arkaig Broch SM 1A - Existing Dun Garsin Broch SM Dun Mor Fort SM Dun Beag Broch SM Knock Ullinish Souterrain SM Section 1 Ullinish Lodge Chambered Cairn SM Ullinish Fort SM Dun Beag Cairn SM Struanmore Chambered Cairn SM 1B - A863 - Bracadale 1C - Tungadal - Sligachan Dun Ardtrack Galleried Dun SM ¯ 0 5 10 20 30 40 Kilometers Location Plan Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. -

Scottish Clans & Castles

Scottish Clans & Castles Starting at $2545.00* Find your castle in the sky Trip details Revisit the past on this leisurely Scottish tour filled with Tour start Tour end Trip Highlights: castle ruins, ancient battlefields, and colorful stories Glasgow Edinburgh • Palace of Holyroodhouse from the country's rich history. • Culloden Battlefield 10 9 15 • Dunvegan Castle Days Nights Meals • Brodie Castle • Stirling Castle • Isle of Skye Hotels: • Novotel Glasgow Centre Hotel • Balmacara Hotel • Glen Mhor Hotel • DoubleTree by Hilton Edinburgh - Queensferry Crossing 2021 Scottish Clans & Castles - 10 Days/9 Nights Trip Itinerary Day 1 Glasgow Panoramic Tour | Welcome Drink Day 2 Stirling Castle | Whisky Distillery Your tour begins at 2:00 PM at your hotel. Take a panoramic tour of Glasgow, Visit Stirling Castle, a magnificent stronghold that was the childhood home of many seeing sights like George Square, Glasgow Cathedral, Kelvingrove Park, Glasgow Scottish kings and queens, including Mary Queen of Scots. Next, head to Glengoyne University and Cathedral, all featured in the popular TV series “Outlander.” Enjoy a Distillery; learn about its two centuries of whisky-making and sample a dram. welcome drink with your group before dining at your hotel. (D) Return to Glasgow, where you will be free to explore and dine as you wish (B) Day 4 Isle of Skye | Dunvegan Castle | Kilt Rock | Kilmuir Day 3 Glencoe | Eilean Donan Castle Graveyard Head into the majestic Highlands and journey by Loch Lomond, across Rannoch Explore the Isle of Skye and learn the history of Bonnie Prince Charlie. Travel to Moor and through Glencoe, often considered one of Scotland's most spectacular Dunvegan Castle, the oldest continuously inhabited castle in Scotland. -

Scotland-The-Isle-Of-Skye-2016.Pdf

SCOTLAND The Isle of Skye A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Scotland at a Glance .............................................................. 22 Packing List ........................................................................... 26 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our new optional Flight + Tour Combo and PrePrePre-Pre ---TourTour Edinburgh Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. Overview Unparalleled scenery, incredible walks, local folklore, and history come together effortlessly in the Highlands and -

History of the Macleods with Genealogies of the Principal

*? 1 /mIB4» » ' Q oc i. &;::$ 23 j • or v HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS. INVERNESS: PRINTED AT THE "SCOTTISH HIGHLANDER" OFFICE. HISTORY TP MACLEODS WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A. Scot., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY AND GENEALOGIES OF THE CLAN MACKENZIE"; "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERON'S;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS ; " "THE " PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER ; " THE HISTORICAL TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLANDS;" "THE HISTORY " OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" " THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE IN 1882-83;" ETC., ETC. MURUS AHENEUS. INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCLXXXIX. J iBRARY J TO LACHLAN MACDONALD, ESQUIRE OF SKAEBOST, THE BEST LANDLORD IN THE HIGHLANDS. THIS HISTORY OF HIS MOTHER'S CLAN (Ann Macleod of Gesto) IS INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/historyofmacleodOOmack PREFACE. -:o:- This volume completes my fifth Clan History, written and published during the last ten years, making altogether some two thousand two hundred and fifty pages of a class of literary work which, in every line, requires the most scrupulous and careful verification. This is in addition to about the same number, dealing with the traditions^ superstitions, general history, and social condition of the Highlands, and mostly prepared after business hours in the course of an active private and public life, including my editorial labours in connection with the Celtic Maga- zine and the Scottish Highlander. This is far more than has ever been written by any author born north of the Grampians and whatever may be said ; about the quality of these productions, two agreeable facts may be stated regarding them. -

River & Green Sample Itinerary

Sample itinerary Day Date Activity Accommodation Sat 12/08/17 Your designated River & Green representative will meet you on arrival at Tigh Na Leigh Guest Edinburgh Airport. He will assist you with the collection of your hire car House, Alyth and provide you with your Holiday Pack, including: route map, licences etc Drive to your accommodation in Perthshire (allow 1 hour 20 minutes) Hotel check-in Dinner Sun 13/08/17 Breakfast Tigh Na Leigh Guest House, Alyth Rainbow trout fishing for 2 fishermen from a boat on Butterstone Loch Dinner Mon 14/08/17 Breakfast Tigh Na Leigh Guest House, Alyth Fly-fishing for salmon, grayling and brown trout for 2 fishermen on the River Isla Dinner Tues 15/08/17 Breakfast Tigh Na Leigh Guest House, Alyth Fly-fishing for salmon, grayling and brown trout for 2 fishermen on the River Isla Dinner Wed 16/08/17 Breakfast Tigh Na Leigh Guest House, Alyth Visit to the Fettercairn malt whisky distillery The remainder of the day free to explore the beautiful and historic countryside of Perthshire and Angus Dinner Thurs 17/08/17 Breakfast Tigh Na Leigh Guest House, Alyth Fly-fishing for salmon, grayling and brown trout for 2 fishermen on the River Isla Dinner Fri 18/08/17 Breakfast Boath House Hotel, near Elgin Hotel check-out Drive to your accommodation near Elgin, with the opportunity to visit Glen Shee, Ballater, Braemar, Glenlivet Distillery and Knockandhu Distillery en-route (allow 3 hours, driving direct) Dinner Sat 19/08/17 Breakfast The Arch Inn, Ullapool Hotel check-out Drive to your accommodation on the north -

Vice-County 104: 2006 Report

PLANTS IN VICE-COUNTY 104: TEN YEARS OF SIX- MONTHLY AND ANNUAL REVIEWS 2006 TO 2015 Stephen J Bungard Table of Contents July to December 2015 .......................................................................................... 2 January to June 2015 ............................................................................................. 5 July to December 2014 .......................................................................................... 7 January to June 2014 ........................................................................................... 10 July to December 2013 ........................................................................................ 12 January to June 2013 ........................................................................................... 14 July to December 2012 ........................................................................................ 16 January to June 2012 ........................................................................................... 18 June to December 2011 ....................................................................................... 20 January to June 2011 ........................................................................................... 22 July to December 2010 ........................................................................................ 23 January to June 2010 ........................................................................................... 25 July to December 2009 ....................................................................................... -

Australians at Parliament 2010 the 16Th Clan Macleod Parliament

Australians at Parliament 2010 younger ones. The discovery of what is called the Moine Thrust where fault lines caused the younger rock to slide down and under the old rock set the geological world ablaze with excitement. Expeditions to the area went on for many years. Names of some 30 geologists participat- ing in an expedition in 1912 are shown in a reproduction of the Inchnadamph Hotel's guest book. Addresses are from Universities in USA, France, Switzerland, Russia, Ireland, England, Scotland and Wales. Tonight is our Official Dinner at the Inchnadamph Hotel, happy company, many in kilts, an excellent meal and absolutely brilliant sunset. Friday 23rd July. Stunning weather continued, 25°C. Morning trip was to Lochinver to visit the Assynt Leisure, Sport, Youth & Learning Centre, a wonderful facility. Community groups raised £65,000 over 15 years and then qualified for support from the National Lottery and European Community, increasing the funds to the £1 million needed. The 16th Clan MacLeod Parliament Afternoon, a boat cruise on Loch Sku to see wildlife, includ- Wed. 21st July. Showers all morning, clearing in the after- ing seals and their pups, and learn further of the local noon but still cloudy. Wendy & I arrive at Inchnadamph geology and history. Our boat guide was fantastic with an Hotel, early afternoon. Emma Halford-Forbes, Parliament endless repetoire of local stories and jokes. Evening saw Registrar and husband Jamie arrive soon after and speed- the group split up with some going to the restaurants of ily handle the necessary paperwork. A trickle of MacLeods Lochinver while others stayed back at Inchnadamph Hotel. -

! ! ! Section 1 Section

Key Corridor Section Divider Route Options Trotternish and Tianavaig SLA Designated and Protected ! Trumpan Landscapes National Scenic Area (NSA) Gillen Wild Land Area (WLA) Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes Site (GDL) Halistra North West Skye SLA Special Landscape Area (SLA) Potential Visual Receptors A Road 0C - Greshornish Stein B Road Minor Road Greshornish SLA Built Properties (100m Buffer) 0B - Garradh Mor Core Paths Greshornish Scottish Hill Tracks (Scotways) 0A - Existing Mountain Walking Route B886 ! Important Outdoor Viewing Location Edinbane A850 Dunvegan Castle GDL Section 0 Dunvegan 0E - Ben Aketil A863 Section 1 Upper Feorlig 0D - Existing ¯ 0 5 10 20 30 40 Balmeanach Kilometers Location Plan WLA 22. Duirinish Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. Crown copyright and database right 2020 all rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number EL273236. Project No: LT91 Project: Skye Reinforcement Title: Figure 6.0 - Landscape and Visual ¯ ! Constraints (Section 0) 0 0.75 1.5 3 4.5 6 Kilometers Scale - 1:100,000 Drawn by: LT Date: 05/03/2020 ! Drawing: 119026-D-LV6.0-1.0.0 Key Corridor Section Divider Trotternish and Route Options Tianavaig SLA Designated and Protected Landscapes Section 0 National Scenic Area (NSA) Wild Land Area (WLA) Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes Site (GDL) Special Landscape Area (SLA) Potential Visual Receptors A Road Portree ! B Road B885 Minor Road 1A - Existing Built Properties (100m Buffer) Core Paths Scottish Hill Tracks (Scotways) Glenmore Mountain Walking Route ! Bracadale Important Outdoor Viewing Location Mugeary ! Section 1 ! ! A87 A863 North West Skye SLA ! 1C - Tungadal - Sligachan ! Section 2 ! 1B - A863 - Bracadale ¯ Sligachan ! ! 0 5 10 20 30 40 Kilometers Location Plan Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. -

Residential Development Site Garrachan | by Dunvegan | Isle of Skye

Residential Development Site Garrachan | By Dunvegan | Isle of Skye A fantastic opportunity to acquire a residential building plot with excellent views over Loch Dunvegan and to the Cuillin mountain range. Solicitors Residential Development Site Don Macleod, Turcan Connell, Princes Exchange, 1 Earl Grey Street, Garrachan | By Dunvegan | Isle of Skye | IV55 8ZR Edinburgh, EH3 9EE Local Authority Portree 21 miles, Inverness 130 miles, Glasgow 230 miles Highland Council, Glenurquhart Road, Inverness, IV3 5NX, Tel 01463 702000 Viewing A fantastic opportunity to acquire a residential Strictly by appointment with Strutt & Parker LLP, The Courier Building, 9 – building plot with excellent views over Loch 11 Bank Lane, Inverness, IV1 1WA, Tel 01463 723592 Dunvegan and to the Cuillin mountain range. Possession Vacant Possession will be given on completion. Offers Offers are to be submitted in Scottish legal terms to the selling agents Strutt & Parker LLP, The Courier Building, 9-11 Bank Lane, Inverness, IV1 1WA. Description A closing date for offers may be fixed and prospective purchasers are advised to register their interest with the selling agents in order to be kept Planning Permission in Principle has been granted for the erection of fully informed of any closing date that may be fixed. a dwelling house and upgrading of shared access track on a plot which extends to approximately 0.32 acres (0.13 ha) or thereby. The terms under which the Planning Permission was granted are Directions contained within the Approval Reference No. 10/04108/PIP, dated 10 From the Skye Bridge, follow the A87 north to Sligachan and thereafter the March 2011, details of which are available on request from our A863 north to Dunvegan. -

The Isle of Skye & Lochalsh

EXPLORE 2020-2021 the isle of skye & lochalsh an t-eilean sgitheanach & loch aillse visitscotland.com Contents 2 Skye & Lochalsh at a glance 4 Amazing activities 6 Great outdoors The Cuillin Hills Hotel is set within fifteen acres of private grounds 8 Touching the past over looking Portree Harbour and the Cuillin Mountain range. 10 Arts, crafts and culture Located on the famous Isle of Skye, you can enjoy one of the finest 12 Natural larder 14 Year of Coasts most spectacular views from any hotel in Scotland. and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips Welcome to… 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit the isle of 36 Leisure activities skye & lochalsh 41 Shopping Fàilte don at t-eilean 46 Food & drink sgitheanach & loch aillse 55 Tours 59 Transport 61 Events & festivals Are you ready for an island adventure unlike any other? The Isle of Skye and the area of Lochalsh (the part of mainland just to the east of Skye) is 61 Local services a dramatic landscape with miles of beautiful coastline, soaring mountain 62 Accommodation ranges, amazing wildlife and friendly people. Come and be enchanted 68 Regional map by fascinating tales of its turbulent history in the ancient castles, defensive duns and tiny crofthouses, and take in some of the special events happening this year. Cover: The view from Elgol, Inspire your creative spirit on the Skye & Isle of Skye Lochalsh Arts & Crafts Trail (SLACA), cross the beautiful Skye Bridge and don’t miss Above image: Kilt Rock, the chance to sample the best local Isle of Skye produce from land and sea in our many Credits: © VisitScotland.