A History of the Gods of Irish Myth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Irish Children's Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016

Irish Children’s Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016 A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2019 Rebecca Ann Long I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Rebecca Long February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………..i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………....iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………....4 CHAPTER ONE: RETRIEVING……………………………………………………………………………29 CHAPTER TWO: RE- TELLING……………………………………………………………………………...…64 CHAPTER THREE: REMEMBERING……………………………………………………………………....106 CHAPTER FOUR: RE- IMAGINING………………………………………………………………………........158 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..……..210 WORKS CITED………………………….…………………………………………………….....226 Summary This thesis explores the recurring patterns of Irish mythological narratives that influence literature produced for children in Ireland following the Celtic Revival and into the twenty- first century. A selection of children’s books published between 1892 and 2016 are discussed with the aim of demonstrating the development of a pattern of retrieving, re-telling, remembering and re-imagining myths -

Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol.117C, Pp.65-99

Gleeson P. (2017) Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, vol.117C, pp.65-99. Copyright: This is the author’s accepted manuscript of an article that has been published in its final definitive form by the Royal Irish Academy, 2017. Link to article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3318/priac.2017.117.04 Date deposited: 07/04/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Luigne Breg and the origins of the Uí Néill By Patrick Gleeson, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University Email: [email protected] Phone: (+44) 01912086490 Abstract: This paper explores the enigmatic kingdom of Luigne Breg, and through that prism the origins and nature of the Uí Néill. Its principle aim is to engage with recent revisionist accounts of the various dynasties within the Uí Néill; these necessitate a radical reappraisal of our understanding of their origins and genesis as a dynastic confederacy, as well as the geo-political landsape of the central midlands. Consequently, this paper argues that there is a pressing need to address such issues via more focused analyses of local kingdoms and political landscapes. Holistic understandings of polities like Luigne Breg are fundamental to framing new analyses of the genesis of the Uí Néill based upon interdisciplinary assessments of landscape, archaeology and documentary sources. In the latter part of the paper, an attempt is made to to initiate a wider discussion regarding the nature of kingdoms and collective identities in early medieval Ireland in relation to other other regions of northwestern Europe. -

Fall 2003 Archipelago

archipelago An International Journal of Literature, the Arts, and Opinion www.archipelago.org Vol. 7, No. 3 Fall 2003 AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC An Exhibiton : Twenty-two Irish and Scottish Gaelic Poems, Translations and Artworks, with Essays and Recitations Fiction: PATRICIA SARRAFIAN WARD “Alaine played soccer with the refugees, she traded bullets and shrapnel around the neighborhood . .” from THE BULLET COLLECTION Poem: ELEANOR ROSS TAYLOR Our Lives Are Rounded With A Sleep Reflection: ANANT KUMAR The Mosques on the Banks of the Ganges: Apart or Together? tr. from the German by Rajendra Prasad Jain Photojournalism: PETER TURNLEY Seeing Another War in Iraq in 2003 and The Unseen Gulf War : Photographs Audio report on-line by Peter Turnley Endnotes: KATHERINE McNAMARA The Only God Is the God of War : On BLOOD MERIDIAN, an American myth printed from our pdf edition archipelago www.archipelago.org CONTENTS AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC 4 Introduction : Malcolm Maclean 5 On Contemporary Irish Poetry : Theo Dorgan 9 Is Scith Mo Chrob Ón Scríbainn ‘My hand is weary with writing’ 13 Claochló / Transfigured 15 Bean Dubh a’ Caoidh a Fir Chaidh a Mharbhadh / A Black Woman Mourns Her Husband Killed by the Police 17 M’anam do sgar riomsa a-raoir / On the Death of His Wife 21 Bean Torrach, fa Tuar Broide / A Child Born in Prison 25 An Tuagh / The Axe 30 Dan do Scátach / A Poem to Scátach 34 Èistibh a Luchd An Tighe-Se / Listen People Of This House 38 Maireann an t-Seanmhuintir / The Old Live On 40 Na thàinig anns a’ churach -

Celtic Solar Goddesses: from Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven

CELTIC SOLAR GODDESSES: FROM GODDESS OF THE SUN TO QUEEN OF HEAVEN by Hayley J. Arrington A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Women’s Spirituality Institute of Transpersonal Psychology Palo Alto, California June 8, 2012 I certify that I have read and approved the content and presentation of this thesis: ________________________________________________ __________________ Judy Grahn, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Date ________________________________________________ __________________ Marguerite Rigoglioso, Ph.D., Committee Member Date Copyright © Hayley Jane Arrington 2012 All Rights Reserved Formatted according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th Edition ii Abstract Celtic Solar Goddesses: From Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven by Hayley J. Arrington Utilizing a feminist hermeneutical inquiry, my research through three Celtic goddesses—Aine, Grian, and Brigit—shows that the sun was revered as feminine in Celtic tradition. Additionally, I argue that through the introduction and assimilation of Christianity into the British Isles, the Virgin Mary assumed the same characteristics as the earlier Celtic solar deities. The lands generally referred to as Celtic lands include Cornwall in Britain, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Brittany in France; however, I will be limiting my research to the British Isles. I am examining these three goddesses in particular, in relation to their status as solar deities, using the etymologies of their names to link them to the sun and its manifestation on earth: fire. Given that they share the same attributes, I illustrate how solar goddesses can be equated with goddesses of sovereignty. Furthermore, I examine the figure of St. -

Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung As a Junction Within Lebor Gabála Érenn

Edinburgh Research Explorer Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn Citation for published version: Thanisch, E 2013, Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn. in Quaestio Insularis: Selected Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium in Anglo-Saxon Norse and Celtic. vol. 13, pp. 69-93. <http://www.asnc.cam.ac.uk/publications/quaestio/Quaestio2012.html> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaestio Insularis General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor 1 Gabála Érenn INTRODUCTION Lebor Gabála Érenn: Content Lebor Gabála Érenn (‘the Book of the Invasion of Ireland’) is the conventional title for a lengthy Irish pseudo-historical text extant in multiple recensions probably compiled during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.2 The text comprises a history of the Gaídil (‘Gaels’) within the context of a universal history derived from the Bible and from Classical historiography.3 Lebor Gabála traces the ancestry of the Gaídil back to Noah and follows their tortuous migrations, spanning many generations, from the Tower of Babel to Ireland via Spain. -

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

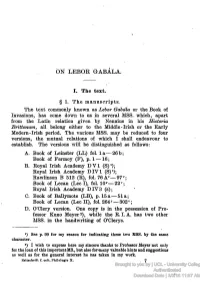

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

Chapter Four Celtic Spirituality

CHAPTER FOUR CELTIC SPIRITUALITY 4.1 Introduction The rediscovery of Celtic spirituality, particularly Celtic prayers and liturgical forms, has led to a popular movement, inter alia, among Anglicans around the world, including those in South Africa. Celtic spirituality has an attraction for both Christian and non-Christian, and often the less formal services are easier for secularized people, who have not been raised in a Christian environment, to accept. A number of alternative Christian communities wit h an accent on recovering Celtic spirituality have been established in recent years in the United Kingdom and in other parts of the world. The Northumbria Community, formed in 1976 (Raine & Skinner 1994: 440) is described as follows: The Community is clearly Christian, but with members from all kinds of Christian tradition, and some with no recognisable church background at all. We are married and single: some are unemployed, most are in secular jobs, some in full-time service which is specifically Christian, others are at home looking after families….Some of the most loyal friends of the Community are not yet committed Christians, but they are encouraged to participate as fully as they feel they can in our life. The Northumbria Community is one of several newly established communities with clear links to Celtic Spirituality. The near-universal appeal and flexibility reflected in the quotation above, is a feature of Celtic spirituality. For many in secularized Europe, the institutional church has lost its meaning, and traditional Christian symbols have no significance. Some of these people are now re-discovering Christianity through the vehicle of Celtic spirituality. -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm

4 (2017) Book Review 1: 1-4 Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2015. 181 pages, £95.00, ISBN (hardcover) 978-1-78316-792-0 REVIEW BY: PHILIP FREEMAN License: This contribution to Entangled Religions is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International). The license can be accessed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or is available from Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbot Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. © 2017 Philip Freeman Entangled Religions 4 (2017) ISSN 2363-6696 http://dx.doi.org/10.13154/er.v4.2017.1-4 Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Understanding Celtic Religion: Revisiting the Pagan Past Edited by Katja Ritari & Alexandra Bergholm. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2015. 181 pages, £95.00, ISBN (hardcover) 978-1-78316-792-0 REVIEW BY: PHILIP FREEMAN The modern scholarly and popular fascination with the myths and religion of the early Celts shows no signs of abating—and with good reason. The stories of druids, gods, and heroes from ancient Gaul to medieval Ireland and Wales are among the best European culture has to offer. But what can we really know about the religion and mythology of the Celts? How do we discover genuine pre-Christian beliefs when almost all of our evidence comes from medieval Christian authors? Is the concept of “Celtic” even a valid one? These and other questions are addressed ably in this short collection of papers by some of the leading scholars in the field of Celtic studies. -

Literature and Learning in Early Medieval Meath

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Literature and learning in early medieval Meath Author(s) Downey, Clodagh Publication Date 2015 Downey, Clodagh (2015) 'Literature and Learning in Early Publication Medieval Meath' In: Crampsie, A., and Ludlow, F(Eds.). Information Meath History and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County. Dublin : Geography Publications. Publisher Geography Publications Link to publisher's http://www.geographypublications.com/product/meath-history- version society/ Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/7121 Downloaded 2021-09-26T15:35:58Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. CHAPTER 04 - Clodagh Downey 7/20/15 1:11 PM Page 1 CHAPTER 4 Literature and learning in early medieval Meath CLODAGH DOWNEY The medieval literature of Ireland stands out among the vernacular literatures of western Europe for its volume, its diversity and its antiquity, and within this treasury of cultural riches, Meath holds a prominence greatly disproportionate to its geographical extent, however that extent is reckoned. Indeed, the first decision confronting anyone who wishes to consider this subject is to define its geographical limits: the modern county of Meath is quite a different entity to the medieval kingdom of Mide from which it gets its name and which itself designated different areas at different times. It would be quite defensible to include in a survey of medieval literature those areas which are now under the administration of other modern counties, but which may have been part of the medieval kingdom at the time that that literature was produced. -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 5

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 5 Introduction Welcome to the fifth lesson. You are now over a third of your way into the lessons. This lesson has took quite a bit longer than I anticipated to come together. I apologise for this, but whilst putting research together, we want the OCW to be as accurate as possible. One thing that I often struggle with is whether ancient Druids used elements in their rituals. I know modern Druids use elements and directions, and indeed I have used them as part of ritual with my own Grove and witnessed varieties in others. When researching, you do come across different viewpoints and interpretations. All of these are valid, but sometimes it is good to involve other viewpoints. Thus, I am grateful for our Irish expert and interpreter, Sean Twomey, for his input and much of this topic is written by him. We endeavour to cover all the basics in our lessons. However, there will be some topics that interest you more than others. This is natural and when you find something that sparks your interest, then I recommend further study into whatever draws you. No one knows everything, but having an overview is a great starting point in any spiritual journey. That said, I am quite proud of the in-depth topics we have put together, especially on Ogham. You also learn far more from doing exercises than any amount of reading. Head knowledge without application is like having a medical consultation and ignoring specialist advice. In this lesson, we are going to look at Celtic artefacts and symbols, continue with our overview of the Book of Invasions, the magick associated with the Cauldron and how to harness elemental magick.