E E Ect of Privacy Regulation on the Data Industry: Empirical Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Featuring Independent Software Vendors

Software Series 32000 Catalog Featuring Independent Software Vendors Software Series 32000 Catalog Featuring Independent Software Vendors .. - .. a National Semiconductor Corporation GENIX, Series 32000, ISE, SYS32, 32016 and 32032 are trademarks of National Semiconductor Corp. IBM is a trademark of International Business Machines Corp. VAX 11/730, 750, 780, PDP-II Series, LSl-11 Series, RSX-11 M, RSX-11 M PLUS, DEC PRO, MICRO VAX, VMS, and RSTS are trademarks of Digital Equipment Corp. 8080, 8086, 8088, and 80186 are trademarks of Intel Corp. Z80, Z80A, Z8000, and Z80000 are trademarks of Zilog Corp. UNIX is a trademark of AT&T Bell Laboratories. MS-DOS, XENIX, and XENIX-32 are trademarks of Microsoft Corp. NOVA, ECLIPSE, and AoS are trademarks of Data General Corp. CP/M 2.2, CP/M-80, CP/M-86 are registered trademarks of Digital Research, Inc. Concurrent DOS is a trademark of Digital Research, Inc. PRIMOS is a trademark of Prime Computer Corp. UNITY is a trademark of Human Computing Resources Corp. Introduction Welcome to the exciting world of As a result, the Independent software products for National's Software Vendor (ISV) can provide advanced 32-bit Microprocessor solutions to customer software family, Series 32000. We have problems by offering the same recently renamed our 32-bit software package independent of microprocessor products from the the particular Series 32000 CPU. NS16000 family to Series 32000. This software catalog was This program was effective created to organize, maintain, and immediately following the signing disseminate Series 32000 software of Texas Instruments, Inc. as our information. It includes the software second source for the Series vendor, contact information, and 32000. -

{PDF} MAC Facil Ebook, Epub

MAC FACIL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pivovarnick | none | 27 Feb 1995 | Prentice Hall (a Pearson Education Company) | 9789688804735 | English, Spanish | Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom MAC Facil PDF Book It's nice to have the options for a floating window or menu bar icon. Your browser does not support the video tag. There are two main disk images we use to carry MacOS versions. Digitally embody awesome characters using just a webcam Get started now Watch it in action. Did you click the "Add People" button at the bottom of the People album? Are you saying to keep Photos open but not use it or should I shut down the app? This information is in the link that Idris provided, which you apparently did not read before responding. You don't need to keep Photos open. Dec 6, AM in response to Esquared In response to Esquared I beg to differ, having designed computers for many years. Otherwise, it would be considered non-secure. Enjoy this tip? While future Macs may have the added hardware required, they currently do not. I don't think you understand how seriously Apple takes security. Apple has added new features, improvements, and bug fixes to this version of MacOS. Bomb Dodge. No menus, no sliders—simply natural text to control your timer. Ask other users about this article Ask other users about this article. Then enter your Apple ID and password and click Deauthorize. People that you mark as favorites appear in large squares at the top of the window. The magical Faces feature is based on facial detection and recognition technologies. -

A Survey of Engineering of Formally Verified Software

The version of record is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/2500000045 QED at Large: A Survey of Engineering of Formally Verified Software Talia Ringer Karl Palmskog University of Washington University of Texas at Austin [email protected] [email protected] Ilya Sergey Milos Gligoric Yale-NUS College University of Texas at Austin and [email protected] National University of Singapore [email protected] Zachary Tatlock University of Washington [email protected] arXiv:2003.06458v1 [cs.LO] 13 Mar 2020 Errata for the present version of this paper may be found online at https://proofengineering.org/qed_errata.html The version of record is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/2500000045 Contents 1 Introduction 103 1.1 Challenges at Scale . 104 1.2 Scope: Domain and Literature . 105 1.3 Overview . 106 1.4 Reading Guide . 106 2 Proof Engineering by Example 108 3 Why Proof Engineering Matters 111 3.1 Proof Engineering for Program Verification . 112 3.2 Proof Engineering for Other Domains . 117 3.3 Practical Impact . 124 4 Foundations and Trusted Bases 126 4.1 Proof Assistant Pre-History . 126 4.2 Proof Assistant Early History . 129 4.3 Proof Assistant Foundations . 130 4.4 Trusted Computing Bases of Proofs and Programs . 137 5 Between the Engineer and the Kernel: Languages and Automation 141 5.1 Styles of Automation . 142 5.2 Automation in Practice . 156 The version of record is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1561/2500000045 6 Proof Organization and Scalability 162 6.1 Property Specification and Encodings . -

Top Functional Programming Languages Based on Sentiment Analysis 2021 11

POWERED BY: TOP FUNCTIONAL PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES BASED ON SENTIMENT ANALYSIS 2021 Functional Programming helps companies build software that is scalable, and less prone to bugs, which means that software is more reliable and future-proof. It gives developers the opportunity to write code that is clean, elegant, and powerful. Functional Programming is used in demanding industries like eCommerce or streaming services in companies such as Zalando, Netflix, or Airbnb. Developers that work with Functional Programming languages are among the highest paid in the business. I personally fell in love with Functional Programming in Scala, and that’s why Scalac was born. I wanted to encourage both companies, and developers to expect more from their applications, and Scala was the perfect answer, especially for Big Data, Blockchain, and FinTech solutions. I’m glad that my marketing and tech team picked this topic, to prepare the report that is focused on sentiment - because that is what really drives people. All of us want to build effective applications that will help businesses succeed - but still... We want to have some fun along the way, and I believe that the Functional Programming paradigm gives developers exactly that - fun, and a chance to clearly express themselves solving complex challenges in an elegant code. LUKASZ KUCZERA, CEO AT SCALAC 01 Table of contents Introduction 03 What Is Functional Programming? 04 Big Data and the WHY behind the idea of functional programming. 04 Functional Programming Languages Ranking 05 Methodology 06 Brand24 -

Comparing UNIX with Other Systems

Comparing UNIX with other systems Timothy DO' Chase Corporate Computer systems, Inc. 33 West Main Street Holmdel, New Jersey he original concept behind this article was to make a grand comparison between UNIX Tand several other well known systems. This was to beall encompassing and packed with vital information summarized in neat charts, tables and graphs. As the work began, the realization settled in that this was not only difficult to do, but would result in a work so boring as to beincomprehensible. The reader, faced with such awealth ofinformation would be lost at best. Conclusions would be difficult to draw and, in short, the result would be worthless. Mtertearfully filling my waste basket with the initial efforts, I regrouped and began by as king myself why would anyone be interested in comparing UNIX with another operating system? There appears to be only two answers. First, one might hope to learn something about UNIX by analogy. IfI understand the file system on MPEN and someone tells me that UNIX is like that except for such and so, then I might be more quickly able to under stand UNIX. This I felt was an unlikely motivation. After all, there are much simpler ways to learn UNIX. Instead, the motivation for comparing UNIX to other systems must come from a need to evaluate UNIX. Ifwe are aware of the features or short comings ofother systems, then we can benefit by evaluating UNIX relative to those systems. Choosing an operating system or computer is a major decision which we can benefit from or be stuck with for a long time. -

David Colignon, Ulg

Introduction to Parallel Programming in OpenMP David Colignon, ULg CÉCI - Consortium des Équipements de Calcul Intensif http://www.ceci-hpc.be Main References • “Parallel Programming with GCC”, Diego Novillo, Red Hat Red Hat Summit, Nashville, May 2006 http://www.airs.com/dnovillo/Papers/rhs2006.pdf • "An Overview of OpenMP", Ruud van der Pas, Oracle IWOMP 2010, Tsukuba, 14-16 June 2010 http://www.compunity.org/training/tutorials/3 Overview_OpenMP.pdf and http://openmp.org/wp/2010/07/iwomp-2010-material-available/ More References: Specification OpenMP, The OpenMP API specification for parallel programming http://openmp.org/ Articles Wikipedia (good summary) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Openmp 32 OpenMP traps for C++ developers http://software.intel.com/en-us/articles/32-openmp-traps-for-c-developers/ Common Mistakes in OpenMP and How To Avoid Them http://www.michaelsuess.net/.../suess_leopold_common_mistakes_06.pdf IWOMP 2009, The 2009 International Workshop on OpenMP (Slides) http://openmp.org/wp/2009/06/iwomp2009/ IWOMP 2010, The 2010 International Workshop on OpenMP (Slides) http://openmp.org/wp/2010/07/iwomp-2010-material-available/ Avoiding and Identifying False Sharing Among Threads http://software.intel.com/en-us/articles/avoiding-and-identifying-false-sharing Tutorials Parallel Programming with GCC, D. Novillo, Red Hat Summit, Nashville, May 2006 http://www.airs.com/dnovillo/Papers/rhs2006.pdf An Overview of OpenMP, IWOMP 2010, Ruud van der Pas, Oracle http://www.compunity.org/training/tutorials/3 Overview_OpenMP.pdf A "Hands-on" Introduction to OpenMP, SC08, Mattsonand Meadows, Intel http://www.openmp.org/mp-documents/omp-hands-on-SC08.pdf Cours OpenMP (en français !) de l'IDRIS http://www.idris.fr/data/cours/parallel/openmp/ Using OpenMP, SC09, Hartman-Baker R., ORNL, NCCS http://www.greatlakesconsortium.org/events/scaling/files/openmp09.pdf OpenMP Tutorial, Barney B., LLNL https://computing.llnl.gov/tutorials/openMP/ Books Using OpenMP - Portable Shared Memory Parallel Programming, by Chapman et al. -

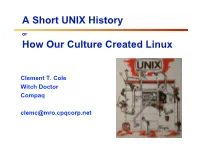

A Short UNIX History How Our Culture Created Linux

A Short UNIX History or How Our Culture Created Linux Clement T. Cole Witch Doctor Compaq [email protected] A UNIX Family History RIG CMU CMU CMU CMU OSF1 Tru64 Linux Accent Mach Mach Mach Linux . 1.X Other Players 2.5 3.0 99 Minix Multics Idris BBN GNU C 386/BSD FreeBSD Generic TCP/IP Net 2.0 Net 1.0 4BSD 4.1A UCB BSD 2BSD 3BSD 4.1BSD 4.2BSD 4.3BSD 4.3Tahoe 4.3Reno 4.4BSD Research X Windows X 10 X 11 32V 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed Ed NT/OS2 NT/Win PWB PWB/UNIX PWB 1.0 PWB 2.0 Sys III Sys V Sys V. SVR3 SVR4 SVR4/ 2 ESMP µSoft/SCO µSoft/Xenix SCO/Xenix SCO/UNIX UNIXWARE ‘72 ‘73 ‘74 ‘75 ‘76 ‘77 ‘78 ‘79 ‘80 ‘81 ‘82 ‘83 ‘84 ‘85 ‘86 ‘87 ‘88 ‘89 ‘90 ‘91 ‘92 ‘93 Clem Cole Themes ◆ Something new is really something old. ◆ The Open Source Culture predates UNIX and Linux. ◆ Evolution is good. ◆ Fighting is not always bad, but learn when it’s good enough and stop fighting. Clem Cole Agenda ◆ Technical History ◆ Legal History ◆ What it all means Clem Cole A Word on Engineers “Good programmers write good programs. Great programmers start and build upon other great programmer’s work.” Unknown origin, often attributed to Fred Brooks. Clem Cole Multics ◆ MULTiplexed Information and Computing Service ❖ or “Many Unbelievably Large Tables In Core Simultaneously.” ❖ Actually very cool system, see: The Multics system; an Examination of its Structure, Elliott I. -

Loadleveler: Using and Administering

IBM LoadLeveler Version 5 Release 1 Using and Administering SC23-6792-04 IBM LoadLeveler Version 5 Release 1 Using and Administering SC23-6792-04 Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 423. This edition applies to version 5, release 1, modification 0 of IBM LoadLeveler (product numbers 5725-G01, 5641-LL1, 5641-LL3, 5765-L50, and 5765-LLP) and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. This edition replaces SC23-6792-03. © Copyright 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991 by the Condor Design Team. © Copyright IBM Corporation 1986, 2012. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Figures ..............vii LoadLeveler for AIX and LoadLeveler for Linux compatibility ..............35 Tables ...............ix Restrictions for LoadLeveler for Linux ....36 Features not supported in LoadLeveler for Linux 36 Restrictions for LoadLeveler for AIX and About this information ........xi LoadLeveler for Linux mixed clusters ....36 Who should use this information .......xi Conventions and terminology used in this information ..............xi Part 2. Configuring and managing Prerequisite and related information ......xii the LoadLeveler environment . 37 How to send your comments ........xiii Chapter 4. Configuring the LoadLeveler Summary of changes ........xv environment ............39 The master configuration file ........40 Part 1. Overview of LoadLeveler Setting the LoadLeveler user .......40 concepts and operation .......1 Setting the configuration source ......41 Overriding the shared memory key .....41 File-based configuration ..........42 Chapter 1. What is LoadLeveler? ....3 Database configuration option ........43 LoadLeveler basics ............4 Understanding remotely configured nodes . -

Introduction to Free Software, February 2008

Free Software Jesús M. González-Barahona Joaquín Seoane Pascual Gregorio Robles PID_00148386 GNUFDL • PID_00148386 Free Software Copyright © 2010, FUOC. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License" GNUFDL • PID_00148386 Free Software Index 1. Introduction........................................................................................ 9 1.1. The concept of software freedom.................................................. 9 1.1.1. Definition ....................................................................... 10 1.1.2. Related terms ................................................................. 11 1.2. Motivations ................................................................................. 12 1.3. The consequences of the freedom of software ........................... 12 1.3.1. For the end user ............................................................ 13 1.3.2. For the public administration ....................................... 14 1.3.3. For the developer ........................................................... 14 1.3.4. For the integrator .......................................................... 15 1.3.5. For service and maintenance providers ......................... 15 1.4. Summary .................................................................................... -

CDO Climate Data Operators

CDO User's Guide Climate Data Operators Version 1.5.9 December 2012 Uwe Schulzweida, Luis Kornblueh { MPI for Meteorology Ralf Quast { Brockmann Consult Contents 1. Introduction 6 1.1. Building from sources.......................................6 1.1.1. Compilation.........................................7 1.1.2. Installation.........................................7 1.2. Usage................................................7 1.2.1. Options...........................................8 1.2.2. Operators..........................................8 1.2.3. Combining operators....................................9 1.2.4. Operator parameter....................................9 1.3. Horizontal grids...........................................9 1.3.1. Grid area weights...................................... 10 1.3.2. Grid description...................................... 10 1.4. Z-axis description.......................................... 13 1.5. Time axis.............................................. 14 1.5.1. Absolute time........................................ 14 1.5.2. Relative time........................................ 14 1.5.3. Conversion of the time................................... 14 1.6. Parameter table........................................... 14 1.7. Missing values............................................ 15 1.7.1. Mean and average..................................... 15 2. Reference manual 16 2.1. Information............................................. 17 2.1.1. INFO - Information and simple statistics........................ 18 -

IDRIS Environment

´ INSTITUT DU DEVELOPPEMENT CENTRE NATIONAL ET DES RESSOURCES DE LA RECHERCHE EN INFORMATIQUE SCIENTIFIQUE SCIENTIFIQUE IDRIS Environment Beginner’s Guide February 29, 2012 This document gives very important recommendations to use efficiently IDRIS environment. Warning: IDRIS environment changes continuously so consult regularly the updates of this doc- ument on our Web server (http://www.idris.fr –> English Corner –> User Support –> IDRIS environment). 1 I.D.R.I.S. – BATIMENTˆ 506 – B.P. 167 – 91403 ORSAY CEDEX FRANCE TELEPHONE :(33) 01.69.35.85.05 – FAX :(33) 01.69.85.37.75 – STANDARD :(33) 01.69.35.85.00 Contents 1 About IDRIS 3 1.1 Missionsandobjectives . ........ 3 2 IDRIS resources 3 2.1 HPCatIDRIS ...................................... 3 2.2 Centre front-end and pre/post-processing IBM X3950 M2 (Ulam)............ 4 2.3 File server SGI ALtix 4700 (Gaya) . ......... 5 2.4 IDRISnetwork .................................... .... 5 3 Connecting to IDRIS systems 6 3.1 Thescientificproject. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ........ 6 3.2 ConnexiontoIDRISSystems . ....... 6 3.3 Managingyouraccount ............................. ...... 8 3.4 Managing your time allocation . ......... 10 3.5 Managingyourdiskusage . ....... 11 4 All about file systems 12 4.1 HOME Directory ........................................ 12 4.2 WORKDIR Directory ...................................... 12 4.3 TMPDIR Directory....................................... 13 4.4 /tmp, /usr/tmp and /var/tmp Directories ........................ 13 4.5 NFS mounts on IDRIS center front-end . -

Towards a Verified Complex Protocol Stack in a Production Kernel: Methodology and Demonstration

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Dartmouth College Ph.D Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2016 Towards A Verified Complex Protocol Stack in a Production Kernel: Methodology and Demonstration Peter C. Johnson Dartmouth College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/dissertations Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Peter C., "Towards A Verified Complex Protocol Stack in a Production Kernel: Methodology and Demonstration" (2016). Dartmouth College Ph.D Dissertations. 51. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/dissertations/51 This Thesis (Ph.D.) is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dartmouth College Ph.D Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS A VERIFIED COMPLEX PROTOCOL STACK IN A PRODUCTION KERNEL: METHODOLOGY AND DEMONSTRATION A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science by Peter C. Johnson DARTMOUTH COLLEGE Hanover, New Hampshire May, 2016 Dartmouth Computer Science Technical Report TR2016-803 Examining Committee: (chair) Sean W. Smith, Ph.D. (co-chair) Sergey Bratus, Ph.D. David F. Kotz, Ph.D. Devin Balkcom, Ph.D. M. Douglas McIlroy, Ph.D. Trent Jaeger, Ph.D. F. Jon Kull, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate Studies ABSTRACT Any useful computer system performs communication and any communication must be parsed before it is computed upon. Given their importance, one might expect parsers to receive a significant share of attention from the security community.