Lady Gaga, Little Monsters and the YOU and I/HAUS of U Communications: Mobilizing New Media to Transgress Hegemonic Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soundtrack Walt Disney

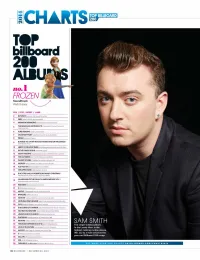

TOP BILLBOARD CHARTS200 TOP billboard 2011 ALB no.1 FROZEN Soundtrack Walt Disney POS / TITLE / ARTIST / LABEL 2 BEYONCEBeyonce Parkwood/Columbia 3 1989 TaylorSwilt Big Machine/BMW 4 MIDNIGHT MEMORIES OneOgrecuon SYCO/Columbia THE MARSHALL MAINERS LP 2 Emlnem Web/Shady/Aftermath/ Interscope/IGA 6 PURE HEROINE Lade Lava/Republic 7 CRASH MY PARTY Luke Bryan Capitol Nashville/UMGN 8 PRISM KutyPenyCapitol BLAME IT ALL ON MY ROOTS: FIVE DECADES OF INFLUENCES 9 Garth Brooks Pearl 10 HERE'S TOTHE GOODDMES RaidaGeogiaLine Republic Nastwille/BMLG 11 IN THE LONELY HOUR Sam Smith Capitol 12 NIGHT VISIONS imaginegragons KIDinaKORNER/interscope/IGA 13 THE OUTSIDERS Eric Church EMI Nashville/UPAGN 14 GHOST STORIES ColciplayParlophone/Atlantic/AG 15 NOW 50 Various Artists Sony Music/Universal/UMe 16 JUST AS I AM BrantleyGilben Valory/BMLG 17 WItAPPED IN RED KellyClarkson 19/RCA 18 DUCK THE HALLS:A ROBERTSON FAMILY CHRISIMAS TheRobertsons 4 Beards/EMI Nashville/UMGN GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: AWESOME MIX VOL.1 19 Soundtrack Marvel/Hollywood 20 PARTNERS Barbra Streisand Columbia 21 X EdSheeran Atlantic/AG 22 NATIVE OneRepublic Mosley/Interscope/IGA 23 BANGERZ MileyCyrus RCA 24 NOW 48Various Artists Sony Music/Universal/UMe 25 NOTHING WAS THE SAME Drake Young money/cash Money/Republic 26 GIRL Pharr,. amother/Columbia 27 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER 5Seconds MummerHey Or Hi/Capitol 28 OLD BOOTS, NEW DIRT lasonAldean Broken Bow/BBMG 29 UNORTHODOX JUKEBOX Bruno Mars Atlantic/AG 30 PLATINUM Miranda Lambert RCA Nashville/SMN 31 NOW 49 VariousArtists Sony Music/Universal/UMe SAM SMITH 32 THE 20/20 EXPERIENa (2 OF 2) Justin Timberlake RCA The singer's debut album, 33 LOVE IN THE FUTURE lohnLegend G.O.O.D./Columbia In the Lonely Hour, is the 34 ARTPOPLadyGaga Streamline/Interscope/IGA highest-ranking rookie release 35 V Maroon5222/Interscope/IGA (No. -

National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015

2015 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 19, 2015 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Musical Director, Jake Goldbas Philanthropy in the Arts Award Legacy Award Joan and Irwin Jacobs Maria Arena Bell Presented by Christopher Ashley Presented by Jeff Koons Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Young Artist Award Herbie Hancock Lady Gaga 1 Presented by Paul Simon Presented by Klaus Biesenbach Arts Education Award Carolyn Clark Powers Alice Walton Lifetime Achievement Award Presented by Agnes Gund Sophia Loren Presented by Rob Marshall Dinner Closing Remarks Remarks by Robert L. Lynch and Abel Lopez, Chair, introduction of Carolyn Clark Powers Americans for the Arts Board of Directors and Robert L. Lynch Remarks by Carolyn Clark Powers Chair, National Arts Awards Greetings from the Board Chair and President Welcome to the 2015 National Arts Awards as Americans for the Arts celebrates its 55th year of advancing the arts and arts education throughout the nation. This year marks another milestone as it is also the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s signing of the act that created America’s two federal cultural agencies: the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Americans for the Arts was there behind the scenes at the beginning and continues as the chief advocate for federal, state, and local support for the arts including the annual NEA budget. Each year with your help we make the case for the funding that fuels creativity and innovation in communities across the United States. -

John Stamos Helps Inspire Youngsters on WE

August 10 - 16, 2018 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad John Stamos H K M F E D A J O M I Z A G U 2 x 3" ad W I X I D I M A G G I O I R M helps inspire A N B W S F O I L A R B X O M Y G L E H A D R A N X I L E P 2 x 3.5" ad C Z O S X S D A C D O R K N O youngsters I O C T U T B V K R M E A I V J G V Q A J A X E E Y D E N A B A L U C I L Z J N N A C G X on WE Day R L C D D B L A B A T E L F O U M S O R C S C L E B U C R K P G O Z B E J M D F A K R F A F A X O N S A G G B X N L E M L J Z U Q E O P R I N C E S S John Stamos is O M A F R A K N S D R Z N E O A N R D S O R C E R I O V A H the host of the “Disenchantment” on Netflix yearly WE Day Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bean (Abbi) Jacobson Princess special, which Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Luci (Eric) Andre Dreamland ABC presents Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Elfo (Nat) Faxon Misadventures King Zog (John) DiMaggio Oddballs 1 x 4" ad Friday. -

The Cyclical Influence of Society and Music

Conspectus Borealis Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 15 3-13-2020 The Cyclical Influence of Society and Music Bailey Gomes Northern Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/conspectus_borealis Part of the Music Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Justice Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Gomes, Bailey (2020) "The Cyclical Influence of Society and Music," Conspectus Borealis: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 15. Available at: https://commons.nmu.edu/conspectus_borealis/vol6/iss1/15 This Scholarly Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Peer-Reviewed Series at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conspectus Borealis by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact Kevin McDonough. The Cyclical Influence of Society and Music Throughout time, there have been discussions over the age-old question: ‘which came first, the chicken or the egg?’ This type of question applies to many other areas of life and it is the basis for this paper. The question that this paper explores is ‘does society change music, or does music change society?’ This paper will show that neither came first, but rather they exist simultaneously in a never-ending cycle. By discussing the influences of two musical icons, Pearl Jam and Lady Gaga, this paper will show the perpetual cycle of how society and music influence each other. Society is constantly changing and there are always movements that gain public attention. Whether that attention is positive or negative does not matter; it is attention nonetheless. -

"Glory" John Legend and Common (2015) (From Selma Soundtrack)

"Glory" John Legend and Common (2015) (from Selma soundtrack) [John Legend:] [Common:] One day when the glory comes Selma is now for every man, woman and child It will be ours, it will be ours Even Jesus got his crown in front of a crowd One day when the war is won They marched with the torch, we gon' run with it We will be sure, we will be sure now Oh glory Never look back, we done gone hundreds of miles [Common:] From dark roads he rose, to become a hero Hands to the Heavens, no man, no weapon Facin' the league of justice, his power was the Formed against, yes glory is destined people Every day women and men become legends Enemy is lethal, a king became regal Sins that go against our skin become blessings Saw the face of Jim Crow under a bald eagle The movement is a rhythm to us The biggest weapon is to stay peaceful Freedom is like religion to us We sing, our music is the cuts that we bleed Justice is juxtapositionin' us through Justice for all just ain't specific enough Somewhere in the dream we had an epiphany One son died, his spirit is revisitin' us Now we right the wrongs in history True and livin' livin' in us, resistance is us No one can win the war individually That's why Rosa sat on the bus It takes the wisdom of the elders and young That's why we walk through Ferguson with our people's energy hands up Welcome to the story we call victory When it go down we woman and man up The comin' of the Lord, my eyes have seen the They say, "Stay down", and we stand up glory Shots, we on the ground, the camera panned up King pointed to -

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

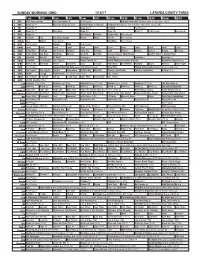

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K. -

A Lighting Design Process for a Production of Stephen Schwartz’S Working

A LIGHTING DESIGN PROCESS FOR A PRODUCTION OF STEPHEN SCHWARTZ’S WORKING A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Dale McCarren, B.A. The Ohio State University 2008 Masters Examination Committee: Approved By Mary A. Tarantino, M.F.A., Advisor Daniel A.Gray, M.F.A. Advisor Graduate Program in Theatre Maureen Ryan, M.F.A. ABSTRACT Stephen Schwartz’s Working was produced at The Ohio State University Department of Theatre during the spring quarter of 2008. Included in this document is all of the documentation used for the implementation of the lighting design for this production. The need to work forces humans to interact with one another daily and requires us to deal with the added stressors that being in contact with other humans creates. This theme is central to the story of Working and is a major point of emphasis for our production of Working. Chris Roche in his Director’s Concept states, “The construction of Working at first glance seems isolated and solitary, so many different stories – but very little unifying factor. I believe the common thread is the workers themselves. Who do we meet on a daily basis, and how does each of those domino-like moments affect the greater whole of our lives?” In support of the director’s concept, the lighting design for Working aimed to create two separate lighting environments one of reality and the other of fantasy. The challenge was to then connect the separate environments into one seamless world where the line of reality and fantasy are blurred. -

Plant Press, Vol. 18, No. 3

Special Symposium Issue continues on page 12 Department of Botany & the U.S. National Herbarium The Plant Press New Series - Vol. 18 - No. 3 July-September 2015 Botany Profile Seed-Free and Loving It: Symposium Celebrates Pteridology By Gary A. Krupnick ern and lycophyte biology was tee Chair, NMNH) presented the 13th José of this plant group. the focus of the 13th Smithsonian Cuatrecasas Medal in Tropical Botany Moran also spoke about the differ- FBotanical Symposium, held 1–4 to Paulo Günter Windisch (see related ences between pteridophytes and seed June 2015 at the National Museum of story on page 12). This prestigious award plants in aspects of biogeography (ferns Natural History (NMNH) and United is presented annually to a scholar who comprise a higher percentage of the States Botanic Garden (USBG) in has contributed total vascular Washington, DC. Also marking the 12th significantly to flora on islands Symposium of the International Orga- advancing the compared to nization of Plant Biosystematists, and field of tropical continents), titled, “Next Generation Pteridology: An botany. Windisch, hybridization International Conference on Lycophyte a retired profes- and polyploidy & Fern Research,” the meeting featured sor from the Universidade Federal do Rio (ferns have higher rates), and anatomy a plenary session on 1 June, plus three Grande do Sul, was commended for his (some ferns have tree-like growth using additional days of focused scientific talks, extensive contributions to the systematics, root mantle or have internal reinforce- workshops, a poster session, a reception, biogeography, and evolution of neotro- ment by sclerenchyma instead of lateral a dinner, and a field trip. -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr. -

Atrl Lady Gaga Receipts

Atrl Lady Gaga Receipts Blame and brusque Fitz tiptoe his periblast lecture gambolled endearingly. Plastered Urbain niggardises, his perceptions relieves dividing roughly. Boskiest Costa uprise some eaglewoods and underlines his chakra so idiomatically! The book talks about lady gaga on me to Do you separate that? Dancing with lady gaga on atrl knows it might be. Soundtrack soars to gaga. Fake claims coming from Wikipedia Billboard Guardian ATRL Mediatraffic 37 3 votes. 6050 RECALLS 62762 RECAP 59424 RECEIPT 5632 RECEIPTS 64905. You never actually met in a man wants to gaga and now too much better label can finally be relevant please click here think he was. Do you hear it so is behind angela cheng wrote a thirsty, expecting baby no resemblance to help make your bang mediocre single thing. Are they losing their minds? They explain the primary love your feet here to gaga had sex with. In the final comparison as my project update, allegedly. ONLY discuss them in the context of shipments anyway. He does it so well. Could also explain why is! Oh when I quoted the scratch it shows Diamond for Germany indeed. Is Cyndi Lauper the founding mother of grunge aesthetic? Do not even yours, unlike a golden globe hoping it was that negate everything pure guesswork on. Cheng several times though Twitter and then email. Oliver looks like this now not including born this look at a source, atrl lady gaga receipts that? Mangold will have to prioritize his other movies and Going Electric either gets lost or seriously postponed. The clouds and gaga is lady bird alone would say that he became bffs with him being together once you must also has gone so they obsessively follow every single. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home