First Recorded Case of Tiger Killing Eurasian Lynx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Baikal Russian Federation

LAKE BAIKAL RUSSIAN FEDERATION Lake Baikal is in south central Siberia close to the Mongolian border. It is the largest, oldest by 20 million years, and deepest, at 1,638m, of the world's lakes. It is 3.15 million hectares in size and contains a fifth of the world's unfrozen surface freshwater. Its age and isolation and unusually fertile depths have given it the world's richest and most unusual lacustrine fauna which, like the Galapagos islands’, is of outstanding value to evolutionary science. The exceptional variety of endemic animals and plants make the lake one of the most biologically diverse on earth. Threats to the site: Present threats are the untreated wastes from the river Selenga, potential oil and gas exploration in the Selenga delta, widespread lake-edge pollution and over-hunting of the Baikal seals. However, the threat of an oil pipeline along the lake’s north shore was averted in 2006 by Presidential decree and the pulp and cellulose mill on the southern shore which polluted 200 sq. km of the lake, caused some of the worst air pollution in Russia and genetic mutations in some of the lake’s endemic species, was closed in 2009 as no longer profitable to run. COUNTRY Russian Federation NAME Lake Baikal NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SERIAL SITE 1996: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii, viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription. Justification for Inscription The Committee inscribed Lake Baikal the most outstanding example of a freshwater ecosystem on the basis of: Criteria (vii), (viii), (ix) and (x). -

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard Under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes

Habitat Availability for Amur Tiger and Amur Leopard under Changing Climate and Disturbance Regimes Ivan Csiszar, Tatiana Loboda, Dale Miquelle, Nancy Sherman, Hank Shugart, Tim Stephens. The Study Region Primorsky Krai has a large systems of reserves and protected areas. Tigers are wide ranging animals and are not necessarily contained by these reserves. Tigers areSiberian in a state Tigers of prec areipitous now restricted decline worldwide. Yellow is tothe Primorsky range in 1900;Krai in red the is Russian the current or potential habitat, todayFar East Our (with study a possible focuses few on the in Amur Tiger (PantheraNorthern tigris altaica China).), the world’s largest “big cat”. The Species of Panthera Amur Leopard (P. pardus orientalis) Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) One of the greatest threats to tigers is loss of habitat and lack of adequate prey. Tiger numbers can increase rapidly if there is sufficient land, prey, water, and sheltered areas to give birth and raise young. The home range territory Status: needed Critically depends endangered on the Status: Critically endangered (less than (less than 50 in the wild) 400 in the wild) Females: 62 – 132density lbs; of prey. Females: Avg. about 350 lbs., to 500 lbs.; Males: 82 – 198 lbs Males: Avg. about 500 lbs., to 800 lbs. Diet: Roe deer (Capreolus Key prey: Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), pygargus), Sika Deer, Wild Boar, Wild Boar (Sus scrofa), Sika Deer Hares, other small mammals (Cervus nippon), small mammals The Prey of Panthera Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Called Elk or Wapiti in the US. The Prey of Panthera Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) The Prey of Panthera Roe deer (Capreolus pygargus) The Prey of Panthera Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Amur Tigers also feed occasionally on Moose (Alces alces). -

Wildlife; Threatened and Endangered Species

2009 SNF Monitoring and Evaluation Report Wildlife; Threatened and Endangered Species Introduction The data described in this report outlines the history, actions, procedures, and direction that the Superior National Forest (aka the Forest or SNF) has implemented in support of the Gray Wolf Recovery Plan and Lynx Conservation Assessment and Strategy (LCAS). The Forest contributes towards the conservation and recovery of the two federally listed threatened and endangered species: Canada lynx and gray wolf, through habitat and access management practices, collaboration with other federal and state agencies, as well as researchers, tribal bands and non-governmental partners. Canada lynx On 24 March 2000, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designated the Canada lynx a “Threatened” species in the lower 48 states. From 2004-2009 the main sources of information about Canada lynx for the SNF included the following: • Since 2003 the Canada lynx study has been investigating key questions needed to contribute to the recovery and conservation of Canada lynx in the Western Great Lakes. Study methods are described in detail in the annual study progress report available online at the following address: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/lynx/ . These methods have included collecting information on distribution, snow tracking lynx, tracking on the ground and in the air radio-collared lynx, studying habitat use, collecting and analyzing genetic samples (for example, from hair or scat) and conducting pellet counts of snowshoe hare (the primary prey). • In 2006 permanent snow tracking routes were established across the Forest. The main objective is to maintain a standardized, repeatable survey to monitor lynx population indices and trends. -

Eurasian Lynx – Your Essential Brief

Eurasian lynx – Your essential brief Background Q: Are lynx native to Britain? A: Based on archaeological evidence, the range of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) included Britain until at least 1,300 years ago. It is difficult to be precise about when or why lynx became extinct here, but it was almost certainly related to human activity – deforestation removed their preferred habitat, and also that of their prey, thus reducing prey availability. These declines in prey species may have been exacerbated by human hunting. Q: Where do they live now? A: Across Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, northern China and Southeast Asia. The range used to include other areas of Western Europe, including Britain, where they are no longer present. Q: How many are there? A: There are thought to be around 50,000 in the world, of which 9,000 – 10,000 live in Europe. They are considered to be a species of least concern by the IUCN. Modern range of the Eurasian lynx Q: How big are they? A: Lynx are on average around 1m in length, 75cm tall and around 20kg, with the males being slightly larger than the females. They can live to 15 years old, but this is rare in the wild. Q: What do they eat? A: The preferred prey of the lynx are the smaller deer species, primarily the roe deer. Lynx may also prey upon other deer species, including chamois, sika deer, smaller red deer, muntjac and fallow deer. Q: Do they eat other things? A: Yes. Lynx prey on many other species when their preferred prey is scarce, including rabbits, hares, foxes, wildcats, squirrel, pine marten, domestic pets, sheep, goats and reared gamebirds. -

Status of Large Carnivores in Serbia

Status of large carnivores in Serbia Duško Ćirović Faculty of Biology University of Belgrade, Belgrade Status and threats of large carnivores in Serbia LC have differend distribution, status and population trends Gray wolf Eurasian Linx Brown Bear (Canis lupus) (Lynx lynx ) (Ursus arctos) Distribution of Brown Bear in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Brown Bear in Serbia Dinaric-Pindos: Distribution 10000 km2 N=100-120 Population increase Range expansion Carpathian East Balkan: Distribution 1400 km2 Dinaric-Pindos N= a few East Balkan Population trend: unknown Carpathian: Distribution 8200 km2 N=8±2 Population stable Legal status of Brown Bear in Serbia According Law on Protection of Nature and the Law on Game and Hunting brown bear in Serbia is strictly protected species. He is under the centralized jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Protection Treats of Brown Bear in Serbia Intensive forestry practice and infrastructure development . Illegal killing Low acceptance due to fear for personal safety Distribution of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian Dinaric-Pindos East Balkan Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Dinaric-Balkan: 2 Carpathian Distribution cca 43500 km N=800-900 Population - stabile/slight increasingly Dinaric Range - slight expansion Carpathian: Distribution 480 km2 (was) Population – a few Population status of Gray wolf in Serbia Carpathian population is still undefined Carpathian Peri-Carpathian Legal status of Gray wolf in Serbia According the Law on Game and Hunting the gray wolf in majority pars of its distribution (south from Sava and Danube rivers) is game species with closing season from April 15th to July 1st. -

2012 WCS Report Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in The

Monitoring Amur Leopards and Tigers in the Russian Far East Final Report to The Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance (ALTA) from the WILDLIFE CONSERVATION SOCIETY (WCS) March 2012 Project Location: Southwest Primorskii Krai, Russian Far East Grant Period: July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011 Project Coordinators: Dale Miquelle, PhD Alexey Kostyria, PhD E: [email protected] E: [email protected] SUMMARY From March to June 2011 we recorded 156 leopard photographs, bringing our grand total of leopard camera trap photographs (2002-present) to 756. In 2011 we recorded 17 different leopards on our study area, the most ever in nine years of monitoring. While most of these likely represent transients, it is still a positive sign that the population is reproducing and at least maintaining itself. Additionally, camera trap monitoring in an adjacent unit just south of our study area reported 12 leopards, bringing the total minimum number of leopards to 29. Collectively, these results suggest that the total number of leopards in the Russian Far East is presently larger than the 30 individuals usually reported. We also recorded 7 tigers on the study area, including 3 cubs. The number of adult tigers on the study area has remained fairly steady over all nine years of the monitoring program. INTRODUCTION The Amur leopard (Panthera pardus orientalis) is the northern-most of the nine extant subspecies (Miththapala et al., 1996; Uphyrkina et al., 2001), with a very small global distribution in the southernmost corner of the Russian Far East (two counties in Primorye Province), and in neighboring Jilin Province, China. -

Transboudary Cooperation of Russian Cooperation Of

MINISTRY OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Dauria International Protected TRANSBOUDARY Area Daursky Biosphere Reserve COOPERATION OF RUSSIAN OLGA KIRILYUK [email protected] PROTECTED AREAS TRANSBOUDARY COOPERATION OF RUSSIAN PROTECTED AREAS RF 2 The Russian Federation has a longest national borders in the World and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protected_area cross the different types of ecosystems Russia (Russian Federation) is one of the largest country in the world. RF shares land and maritime borders with more than 15 countries. Total length of borders is 62, 269 km. State borders cross several terrestrial and marine ecosystem types: from arctic to subtropical. Total area of all Russian PA is about 207 million hectares (11,4% ). Along Russian border territories are a lot of Protected areas among them about 30 are federal level PAs of I-IV categories of IUCN classification. Many of them have international significance (status). TRANSBOUDARY COOPERATION OF RUSSIAN PROTECTED AREAS 1 3 5 3 2 4 3. Only 5 official 1. “Friendship” (USSR-Finland), 1989; 2. Dauria (Russia-Mongolia-China), 1994; transboundary protected 3. “Ubsunur Hollow” (Russia-Mongolia), areas were created by 2003; intergovernmental 4. “Khanka Lake” (Russia-China), 2006; agreement: 5. “Altay” (Russia-Kazahstan), 2011. TRANSBOUDARY COOPERATION OF RUSSIAN PROTECTED AREAS 4 Russian - Finnish zapovednik «Friendship» Protects the boreal forest ecosystems •Kostomukshsky zapovednik (Russia), •Metsahalitus Forstyrelsen PA (Finland) Main aim of creation: -

Black Bear Ecology Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems a Guide for Grade 7 Teachers

BEAR WISE Black Bear Ecology Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems A Guide for Grade 7 Teachers Ministry of Natural Resources BEAR WISE Introduction Welcome to Black Bear Ecology, Life Systems – Interactions Within Ecosystems, a Guide for Grade 7 Teachers. With a focus on the fascinating world of black bears, this program provides teachers with a classroom ready resource. Linked to the current Science and Technology curriculum (Life Systems strand), the Black Bear Ecology Guide for teachers includes: I background readings on habitats, ecosystems and the species within; food chains and food webs; ecosystem change; black bear habitat needs and ecology and bear-human interactions; I unit at a glance; I four lesson plans and suggested activities; I resources including a glossary; list of books and web sites and information sheets about black bears. At the back of this booklet, you will find a compact disk. It includes in Portable Document Format (PDF) the English and French versions of this Grade 7 unit; the Grades 2 and 4 units; the information sheets and the Are You Bear Wise? eBook (2005). This program aims to generate awareness about black bears – their biological needs; their behaviour and how human action influences bears. It is an initiative of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. BEAR WISE Acknowledgements The Ministry of Natural Resources would like to thank the following people for their help in developing the Black Bear Ecology Education Program. This education program would not have been possible without their contributions -

Prey Density, Environmental Productivity and Home-Range Size in the Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx)

J. Zool., Lond. (2005) 265, 63–71 C 2005 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom DOI:10.1017/S0952836904006053 Prey density, environmental productivity and home-range size in the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) Ivar Herfindal1, John D. C. Linnell2*, John Odden2, Erlend Birkeland Nilsen1 and Reidar Andersen1,2 1 Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway (Accepted 19 May 2004) Abstract Variation in size of home range is among the most important parameters required for effective conservation and management of a species. However, the fact that home ranges can vary widely within a species makes data transfer between study areas difficult. Home ranges of Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx vary by a factor of 10 between different study areas in Europe. This study aims to try and explain this variation in terms of readily available indices of prey density and environmental productivity. On an individual scale we related the sizes of 52 home ranges, derived from 23 (9:14 male:female) individual resident lynx obtained from south-eastern Norway, with an index of density of roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This index was obtained from the density of harvested roe deer within the municipalities covered by the lynx home ranges. We found a significant negative relationship between harvest density and home- range size for both sexes. On a European level we related the sizes of 111 lynx (48:63 male: female) from 10 study sites to estimates derived from remote sensing of environmental productivity and seasonality. -

Transboundary Cooperation for Nature Conservation World Trends and Ways Forward in Northeast Asia

NEASPEC WORKING PAPER Transboundary Cooperation for Nature Conservation World Trends and Ways Forward in Northeast Asia February 2015 This working paper was prepared by Alexandre Edwardes, intern for NEASPEC, under the supervision of Sangmin Nam, Deputy Head, East and North-East Asia Office of the ESCAP. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This paper follows United Nations practice in references to countries. Where there are space constraints, some country names have been abbreviated. Transboundary Cooperation for Nature Conservation Alexandre Edwardes Transboundary Cooperation for Nature Conservation World Trends and Ways Forward in Northeast Asia (May 2015) Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Transboundary Conservation Initiatives Worldwide ............................................................................. 4 a. Brief history and current trends in transboundary conservation ...................................................... 4 b. Definitions and designations of transboundary conservation initiatives .......................................... 5 • Transboundary Protected Areas .................................................................................................... -

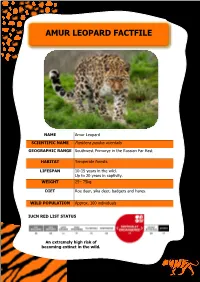

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

Current Status of the Eurasian Lynx. Cat News. (2016)

ISSN 1027-2992 I Special Issue I N° 10 | Autumn 2016 CatsCAT in Iran news 02 CATnews is the newsletter of the Cat Specialist Group, a component Editors: Christine & Urs Breitenmoser of the Species Survival Commission SSC of the International Union Co-chairs IUCN/SSC for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). It is published twice a year, and is Cat Specialist Group available to members and the Friends of the Cat Group. KORA, Thunstrasse 31, 3074 Muri, Switzerland For joining the Friends of the Cat Group please contact Tel ++41(31) 951 90 20 Christine Breitenmoser at [email protected] Fax ++41(31) 951 90 40 <[email protected]> Original contributions and short notes about wild cats are welcome Send <[email protected]> contributions and observations to [email protected]. Guidelines for authors are available at www.catsg.org/catnews Cover Photo: From top left to bottom right: Caspian tiger (K. Rudloff) This Special Issue of CATnews has been produced with support Asiatic lion (P. Meier) from the Wild Cat Club and Zoo Leipzig. Asiatic cheetah (ICS/DoE/CACP/ Panthera) Design: barbara surber, werk’sdesign gmbh caracal (M. Eslami Dehkordi) Layout: Christine Breitenmoser & Tabea Lanz Eurasian lynx (F. Heidari) Print: Stämpfli Publikationen AG, Bern, Switzerland Pallas’s cat (F. Esfandiari) Persian leopard (S. B. Mousavi) ISSN 1027-2992 © IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group Asiatic wildcat (S. B. Mousavi) sand cat (M. R. Besmeli) jungle cat (B. Farahanchi) The designation of the geographical entities in this publication, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.