Shem Hamephorash: Ineffable Name for God in Kabbalah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aleister Crowley's Illustrated Goetia

(}rIIEl{ TITLES FROM NEW FALCON PUBLICATIONS ( '0.\'111ic Trigger: Final Secret ofthe Illuminati Afeister Crowfey)s Prometheus Rising By Robert Anton Wilson Undoing Yourself With Energized Meditation The Psychopath's Bible I[[ustratecf Goetia: By Christopher S. Hyatt, Ph.D. Gems From the Equinox The Pathworkings ofAleister Crowley sexuaL Evocation By Aleister Crowley Info-Psychology The Game ofLife By Timothy Leary, Ph.D. By Sparks From the Fire ofTime By Rick & Louisa Clerici Lon Mifo DuQuette and Condensed Chaos: An Introduction to Chaos Magick By Phil Hine Christopfier S. Hyatt} ph.D. The Challenge ofthe New Millennium By Jerral Hicks, Ed.D. The Complete Golden Dawn System ofMagic The Golden Dawn Tapes-Series I, II, and III By Israel Regardie I[[ustratecC By Buddhism and Jungian Psychology By J. Marvin Spiegelman, Ph.D. David P. Wifson The Eyes ofthe Sun: Astrology in Light ofPsychology By Peter Malsin Metaskills: The Spiritual Art ofTherapy By Amy Mindell, Ph.D. Beyond Duality: The Art ofTranscendence By Laurence Galian Virus: The Alien Strain By David Jay Brown The Montauk Files: Unearthing the Phoenix Conspiracy By K.B. Wells Phenomenal Women: That's Us! By Dr. Madeleine Singer Fuzzy Sets By Constantin Negoita, Ph.D. And to get your free catalog of all of our titles, write to: New Falcon Publications (Catalog Dept.) 1739 East Broadway Road, #1 PMB 277 Tempe, Arizona 85282 U.S.A NEW FALCON PUBLICATIONS And visit our website at http://www.newfalcon.com TEMPE, ARIZONA, U.S.A. Copyright © 1992 V.S.E.S.S. All rights reserved. No part of this book, in part or in whole, may be reproduced, transmitted, or utilized, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, record ing, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except for brief quota tions in critical articles, books and reviews. -

Imperial Arts, Volume

^ Mlf.V. I, the sole legitimate heir to the ancient magical traditions of King Solomon the Wise, propose to demonstrate his powerful art in its true and proper form so that it will not pass from history unknown. I do not hope hereby to convince the skeptic or to explain the meaning of these rituals to the mystic, but rather to merely offer insight into their procedures and the relevance thereof, so that those who have such an interest may distinguish them from the impostures of the ignorant and the slothful. Understand that King Solomon possessed wisdom such as no man to come after him would ever have, allowing him to transmute the vengeance and enmity of the world earned by his father into friendship, wealth, and power. Through this art, passed to his son and thence, the wise man may yet attain the grace bestowed upon Solomon through the service of the spirits sworn to his covenant under the names of his infinite God. Imperial Arts Of John R. King IV A Record of Experiments in Demonology Volume One Contents The Method of Science Introduction to the Subject Review of Practical Elements The Evocations The Results Afterthoughts Acknowledgements The Method of Science My interest in demonology began at age eleven, in conversation with a "religious brother" of one of the Catholic orders. At the time, he was making a point about the miracles of saints, namely that these events were special endowments from God and were signs of spiritual grace. Having had some fascination with the supernatural from a young age, I asked of this man how it would be possible for Oriental mystics, the magicians of Pharaoh, and other non-saintly individuals to perform similar miracles. -

Goetia Vel Clavicula Salamonis Regis

GOETIAVELCLAVICULASALOMONISREG ISGOETIAVELCLAVICULASALOMONISR EGISGOETIAVELCLAVICULASALOMONIS REGISGOETIAVELCLAVICULASALOMONI SREGISGOETIAVELCLAVICULASALOMO NISREGISGOETIAVELCLAVICULASALOM ONISREGISGOETIAVELCLAVICULASALO MONISREGISGOETIAVELCLAVICULASAL OMONI SREGI SGOET GOETIA IAVEL CLAVICULASALOMONISREGISGOETIAVE LCLAVICULASALOMONISREGISGOETIAV ELCLAVICULASALOMONISREGISGOETIA VELCLAVICULASALOMONISREGISGOETI AVELCLAVICULASALOMONISREGISGOET IAVELCLAVICULASALOMONISREGISGOE TIAVELCLAVICULASALOMONISREGISGO ETIAVELCLAVICULASALOMONISREGIS 1 GOETIA EPIKALOUMAI SE TON EN TW KENEO PNEUMATI, DEINON, AORAUON, PANTOKRATORA, QEON QEOU, FQEROPOION, KAI ERHMOPOION, O MISWN OIKIAN EUSTAQOUSAN, WS EXEBRSQHS EK UHS AIGUPUIOU KAI EXO CWRAS. EPONOMASQHS O PANTA RHSSWN KAI MH NIKWMENOS. EPIKALOUMAI SE TUFWN SHQ TAS SES MANTEIAS EPITELW, OTI EPIKALOUMAI SE TO SON AUQENTIKO SOU ONOMA EN OIS OU DUNE PARAKOUSAI IWERBHQ, IWPAKERBHQ, IWBOLCWSHQ, IWPATAQNAX, IWSWRW, IWNEBOUTOSOUALHQ, AKTIWFI, ERESCIGAL, NEBOPOWALHQ, ABERAMENTQOWU, LERQEXANAX, EQRELUWQ, NEMAREBA, AEMINA, OLON HKE MOI KAI BADISON KAI KATEBALE TON DEINON MAQERS. RIGEI KAI PUREIW AUTOS HDIKHSEN TON ANQRWPON KAI TO AIMA TOU TUFWNOS EXECUSEN PAR' EAUTW. DIA TOUTO TAUTA POIEW KOINA. THE BOOK OF THE GOETIA OF SOLOMON THE KING TRANSLATED INTO THE ENGLISH TONGUE BY A DEAD HAND AND ADORNED WITH DIVERS OTHER MATTERS GERMANE DELIGHTFUL TO THE WISE THE WHOLE EDITED, VERIFIED, INTRODUCED AND COMMENTED BY ALEISTER CROWLEY SOCIETY FOR THE PROPAGATION OF RELIGIOUS TRUTH BOLESKINE, FOYERS, INVERNESS 1904 This re-set electronic edition prepared by Celephaïs Press somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills, 2003 E.V. Last revised August 2004 E.V. K O D S E LI M O H A B I O M O K PREFATORY NOTE A.G.R.C. A.R.G.C THIS translation of the First Book of the “Lemegeton” (now for the first time made accessible to English adepts and students of the Mysteries) was done, after careful collation and edition, from numer- ous MSS. in Hebrew, Latin, French and English, by G. -

LEMEGETON CLAVICULA SALOMONIS REGIS Reworked, Written and Inspired from the Original Manuscript by Michael W

1 The GOETIA THE LESSER KEY OF SOLOMON THE KING LEMEGETON CLAVICULA SALOMONIS REGIS Reworked, Written and inspired from the original manuscript by Michael W. Ford Illustrated by Elda Isela Ford The Luciferian Edition, Houston, TX 2003 2 The Goetia Written and presented anew by Michael W. Ford ~ Akhtya Seker Arimanius To Restore the Sorcerous Path and the Art of Luciferian Ascension Illustrations also by Original Manuscript Sigils, Aleister Crowley reworked Sigils from the 1904-1976 Equinox Edition with new drawings. Inspired from the original manuscript edition, also the irreplaceable Goetia translated by SAMUEL LIDDELL MACGRAGOR MATHERS EDITED, ANNOTATED AND INTRODUCED BY ALEISTER CROWLEY Re-Print Issued by Equinox Publishing, London, 1976. Illustration Listing at end of Book. Also inspired by the meticulous and scholarly Illustrated Second Edition with annotations by ALEISTER CROWLEY and edited by HYMENAEUS BETA (Weiser 1995) The edition is intended as a personal grimoire Working. My original focus was to rework the Goetia in a modern Luciferian form, which focused on the development of the Will and the Self through Antinomian Left Hand Path techniques. The Author and Publisher accept no responsibility for the misuse of this edition. The Author wishes to thank- Jack Ehrhardt, Ms. Napper, Frater Scorpius Nokmet, Frater A.S.L., Dana Dark, a special thank you to fellow initiate Marie Buckner, Ugly Shyla and mother, Robert Mahar, Shemyaza of Immortal Coil Designs, Magus Books and all of the Brothers and Sisters of The Order of Phosphorus. Lucifer Triumphans! 3 Illumination Spell of the Seeker The Perception of the Serpent’s Mind who in the Dream of the Celestial and Infernal shall walk between the Worlds. -

Appendix 2 the Nature of Numbers

Appendix 1 Gematria Tables Hebrew No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Name ~leph' Beth Gimel Daleth Heh Vav Zain Cheth Teth N 3 3 'I n 'I 7 n a No. 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 Name Yod Kaph Lamed Mem Nun Samekh Ayin Peh Tzaddi 9 I 7 P 2 0 tt B 3 No. 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 Name Qoph Resh Shin Tav Final Final Final Final Final Kaph Mem Nun Peh Tzaddi 3 7 w n 7 P 1 7 Y 1 When Aleph is written large W its value is 1000. Qabalah of the 9 chambers is a method where the number is reduced to the smallest single digit. This is called Thesophic Reduction For Example: 800 = 8 + 0 + 0 = 8 Mem Kaph D 0 1 3 il n D 7 7 - 600 60 6 500 50 5 400 40 4 Final Tzaddi Teth Final Peh Cheth Final Ayin Zain Tzaddi Peh Nun T 3 tll 7 o n f D t 900 90 9 800 80 8 700 70 7 Roman Letters in Qabalah Simplex No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 A B C D E F G H I (J) L 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 M N 0 P Q R S T v (u) x 2 1 22 Y z I have seen several methods to derive the numerical values of English letters. This is the simplest and makes the most sense. -

The Grimoire

LIBER SATANGELICA Nathaniel J. Harris Soror Tekla 484, 3*, TOPh Introduction; THE GRIMOIRE The importance of the classical grimoire, and the more personal books of spells attributed to various witches and cunning folk, has been greatly undervalued in more recent studies of the craft. Nevertheless, the knowledge of the black arts and the important place of the grimoire has been well documented since before the middle ages and we have a great storehouse of records at our disposal, both from the sorcerer’s themselves and those who prosecuted them. This is not limited to East Anglia or even England. Consider the confession of Jubertus of Bavaria, tried in 1437. Apart from the more or less typical flights to nocturnal assemblies and the killing of infants the aforesaid Jobertus said and confessed, under ‘freely given oath’.. “.. that for ten years and more he served a certain powerful man in Bavaria who was called Johannes Cunalis, who is a priest and plebanus, in a city called Munich.. Likewise he said and confessed that this Johannes Cunalis had in his possession a librum de nigromancia, and that when he who spoke opened this book at once there appeared to him three Demons, one named Luxuriosus, another Superbus, and a third Avarus, all of them Devils… Likewise, he said and confessed that he had proposed to blind Johanneta, the widow of Johannes Paganus of the present place, because she displeased him. With two keys he had traced her image, in a manner and form which he explained in the examination; he did this on a Sunday, depicting her -

Qabalah, Qliphoth E Magia Goética

QABALAH, QLIPHOTH E MAGIA GOÉTICA TABELA DE CONTEÚDO Clique abaixo para ir diretamente aos capítulos PREFÁCIO A ÁRVORE DA VIDA ANTES DA QUEDA Introdução A QABALAH E O LADO ESQUERDO A ORIGEM DA QABALAH AS DEFINIÇÕES DA QABALAH AS SEPHIROTH E A ÁRVORE DA VIDA AIN SOPH E AS SEPHIROTH OS VINTE E DOIS CAMINHOS A ÁRVORE DA VIDA ANTES DA QUEDA LÚCIFER-DAATH A QUEDA DE LÚCIFER A ABERTURA DO ABISMO LILITH-DAATH E A SOPHIA CAÍDA A NATUREZA DO MAL A SEPHIRA GEBURAH E A ORIGEM DO MAL GEBURAH E SATÃ GEBURAH E A CRIAÇÃO OS MUNDOS DESTRUÍDOS OS REIS DO EDOM GEBURAH E O ZIMZUM O ROMPIMENTO DOS VASOS AS QLIPHOTH DEMONOLOGIA A DEMONOLOGIA QLIPHOTICA DE ELIPHAS LÉVI KELIPPATH NOGAH AS QLIPHOTH E AS SHEKINAH A SITRA AHRA A PRIMORDIALIDADE DO MAL A SITRA AHRA COMO INFERNO CENTELHAS NA SITRA AHRA ADÃO BELYYA'AL A LUZ NEGRA A ÁRVORE EXTERNA A ÁRVORE DO CONHECIMENTO DUAS ÁRVORES E DUAS VERSÕES DA TORAH A SERPENTE NO JARDIM DO ÉDEN: O INFRINGIMENTO DO MAL O MAL VEM DO NORTE A VISÃO SOBRE O MAL NA QABALAH A RAIZ DO MAL O QUE É O MAL? A INICIAÇÃO QLIPHOTICA AS DEZ QLIPHOTH LILITH GAMALIEL SAMAEL A'ARAB ZARAQ THAGIRION GOLACHAB GHA'AGSHEBLAH O ABISMO SATARIEL GHAGIEL THAUMIEL AS INVOCAÇÕES QLIPHOTICAS A ABERTURA DOS SETE PORTAIS A INVOCAÇÃO DE NAAMAH A INVOCAÇÃO DE LILITH A INVOCAÇÃO DE ADRAMELECH A INVOCAÇÃO DE BAAL OS TÚNEIS QLIPHOTICOS PERAMBULANDO ATRAVÉS DO TÚNEL THANTIFAXATH VISUALIZAÇÃO DE THANTIFAXATH MAGIA GOÉTICA MAGIA SALOMÔNICA SHEMHAMFORASH A DEMONOLOGIA DA GOETIA EVOCAÇÕES E INVOCAÇÕES O RITUAL MÁGICO DA GOETIA AS FERRAMENTAS RITUAIS UM ENCANTAMENTO DE DEMÔNIOS DE ACORDO COM O GRIMORIUMVERUM OS DEMÔNIOS DO GRIMORIUM VERUM OS 72 DEMÔNIOS DA GOETIA CORRESPONDÊNCIAS OCULTAS MAGIA GOÉTICA PRÁTICA EXPERIÊNCIAS GOÉTICAS EPÍLOGO BIBLIOGRAFIA APÊNDICE CORRESPONDÊNCIAS QLIPHOTICAS E MITOLÓGICAS PREFÁCIO Os conceitos em relação à magia, forças mais elevadas, deuses e como contatá- los são muito provavelmente tão velhos quanto a própria humanidade. -

Demon Names and Meanings Abaddon - (Hebrew) Destroyer, Advisor

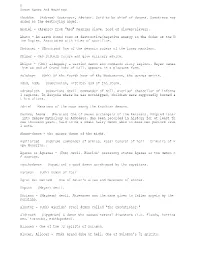

Demon Names And Meanings Abaddon - (Hebrew) Destroyer, Advisor. Said to be chief of demons. Sometimes reg arded as the destroying angel. Abdiel - (Arabic) from "Abd" meaning slave. Lord of slaves/slavery. Abatu - An earth bound form of destructive/negative energy in the Order of the N ine Angles. Associated with rites of sacrifice. Abduxuel - (Enochian) One of the demonic rulers of the lunar mansions. Abigar - Can fortell future and give military advice. Abigor - (Unk) allegedly a warrior demon who commands sixty legions. Weyer names him as god of Grand Duke of Hell. Appears in a pleasant form. Aclahayr - (Unk) Of the fourth hour of the Nuctemeron, the genius spirit. Adad, Addu - (Babylonian, Hittite) god of the storm. Adramalech - (Samarian) devil. Commander of Hell. Wierius' chancellor of inferna l regions. In Assyria where he was worshipped, children were supposedly burned a t his alters. Adriel - Mansions of the moon among the Enochian demons. Aeshma, Aesma - (Persian) One of seven archangels of the Persians. Adopted later into Hebrew mythology as Asmodeus. Has been recorded in history for at least th ree thousand years. Said to be a small hairy demon able to make men perform crue l acts. Ahazu-demon - the siezer demon of the night. Agaliarept - (Hebrew) commander of armies. Aussi General of hell - Grimoire of P ope Honorius.. Agares or Aguares - (Unk) devil. Wierius' hierarchy states Agares is the demon o f courage. Agathodemon - (Egyptian) a good demon worshipped by the egyptians. Agramon - (Unk) Demon of fear Agrat-bat-mahlaht - One of Satan's wives and demoness of whores. Ahpuch - (Mayan) devil. -

Demon List.Pdf

Demon List Version II beta 8-11-04 compiled by Terry Thayer [email protected] ~ Color Key ~ Entries in black are from http://colucifer.cjb.net, by Reverend Satrinah Nagash Entries in orange are by S. Connolly Entries in dark blue are from Usenet's alt.magick FAQ: REFERENCE -- "DEMONS" File, by “reficul” and Paul Harvey, with a few notes by Bryan J. Maloney Entries in dark green are from The Satanic Bible, by Anton Szandor LaVey Entries in violet are from http://en.wikipedia.org Entries in teal are from http://members.tripod.com/MoreEsoteric Entries in grey are from the Necronomicon Spellbook, edited by “Simon.” Entries in lavender are from The Goetia, compiled and translated by S.L. “MacGregor” Mathers, with editing and additional material by Aleister Crowley Entries in turquoise are from the Grimoirium Verum, translated by Plangiere, Jesuit Dominicane Entries in bright green are from the Grimoirium Imperium, by John Dee Entries in brown are from http://www.free-webspace.biz/satanspowers/Satans Power Home.html, by High Priest Dann Tehuti Entries in dark red italics are my own notes. All biblical references are from NIV. ~ A ~ Aamon – One of Astaroth's assistants. He knows past and future, giving that knowledge to those who had made a pact with Satan. According to some authors he has forty legions of demons under his command, having the title of prince. There is no agreement on how to depict him, being sometimes portrayed as an owl-headed man, and sometimes as a wolf-headed man with snake tail. Although some demonologists have associated his name with the Egyptian god Ammon, it is more plausible its derivation from the Semitic god Baal Hammon, also worshipped in some areas of northern Egypt that had been in contact with Semitic tribes. -

The Lesser Key of Solomon.Pdf

This project represents a work of LOVE. All texts so far gathered, as well as all future gatherings aim at exposing interested students to occult information. Future releases will include submissions from users like YOU. For some of us, the time has come to mobilize. If you have an interest in assisting in this process - we all have strengths to bring to the table. email : [email protected] Complacency serves the old gods. THE LESSER KEY OFSOLOMON LEMEGETON CLAVICULA SALOMONIS Detailing the Ceremonial Art of Commanding Spirits Both Good and Evil Joseph H. Peterson, Editor ®WEISERBoOKS York Beach, Maine, USA First published in 2001 by Weiser Books P.O. Box 612 York Beach, ME 03910-0612 www.weiserbooks.com Copyright © 2001 Joseph H. Peterson All rights reserved. No part ofthis publication may be reproduced or trans mitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Weiser Books. Reviewers may quote brief passages. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clavicula Salomonis. English The lesser key of Solomon lemegeton clavicula Salomonis / Joseph H. Peterson, editor p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57863-22o-X (alk. paper);ISBN 1-57863-256-0 (pbk, : alk. paper) 1. Magic-Early works to 1800. 2. Magic, Jewish-Early works to 1800. 1. Peterson, Joseph H. II. Title. BF1601.C4313 2001 133.4'3-dc21 00-068529 MV Typeset in 12 pt. Adobe Caslon Cover design by Ed Stevens Printed in the United States ofAmerica 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 8 7 6 5 432 1 The paper used in this publication meets all the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992 (RI997). -

The Magic Wand

Toward a Rectification of Demonology S.1: Statement of Purpose I. This paper has been prepared for ritualists whom wish to take part of the darker side of magick. It is not intended for use by inexperienced people; and indeed could prove to be dangerous. The steps given here are simple, few in number and easily memorized and followed yet they must be followed out precisely as given. Failure to do so could result in unfavorable circumstances. II. To Love Belial is to Love Life. Satan Takes Care of His Own. S.2: The Pantheon of Worship I. Qliphoth i. Thamiel ii. Chaigedel iii. Sateriel iv. Gamehioth v. Galeb vi. Tagaririm vii. Harab-Serapel viii. Samael ix. Gamaliel x. Lilith - 1 - www.sacred-magick.com | The Esoteric Library II. Archdevils i. Satan ii. Apollyon iii. Theulus iv. Asmodeus v. Incubus vi. Ophis vii. Antichrist viii. Ashtaroth ix. Abaddon x. Mammon III. Schemhamphorash a. Kings Bael Paimon Beleth Purson Asmodeus Vine Balaam Zagan Belial b. Dukes Agares Berith Valefor Ashtaroth Barbatos Focalor Gusion Vepar Eligos Vual Zepar Crocell Bathin Alloces Sallos Murmur Aim Gremory Bune Vapula Haures Amdusias Dantalion c. Princes Vassago Stolas Sitri Orobas Ipos Seere Gaap d. Marquises Samigina Shax Amon Orias Leraje Andrash Naberius Andrealphus - 2 - www.sacred-magick.com | The Esoteric Library Ronove Cimeies Forneus Decarabia Marchosias Sabnock Phenex e. Presidents Marbas Foras Buer Gaap Botis Malphas Marax Haagenti Glasya-Labolas Caim Ose Amy Zagan Valac f. Earls Botis Raum Marax Vine Glasya-Labolas Bifrons Ronove Andromalius Furfur Halphas g. Knights Furcas IV. Terrestrial Devils i. Surgat ii. -

Minor Card Decan Ruling Planet Shem. Angel Goetic

MINOR DECAN RULING SHEM. GOETIC GD RANK PLANET GOETIC CARD PLANET ANGEL RUDD 2 of 0-5 Aries Mars Vehuel 1) Bael King Sun 49) Crocell Wands 5-10 Aries Daniel 37) Phenex Marquise Moon 50) Furcas 3 of 10-15 Aries Sun Heahaziah 2) Agares Duke Venus 51) Balam Wands 15-20 Aries Amamiah 38) Halphas Earl Mars 52) Alloces 4 of 20-25 Aries Venus Nanael 3) Vassago Prince Jupiter 53) Camio Wands 25-30 Aries Nithael 39) Malphas President Mercury 54) Murmus 5 of Disks 0-5 Taurus Mercury Mebahiah 4) Gamigin Marquise Moon 55) Orobas 5-10 Poiel 40) Raum Earl Mars 56) Gemory Taurus 6 of Disks 10-15 Moon Nemamiah 5) Marbas President Mercury 57) Oso Taurus 15-20 Leilael 41) Focalor Duke Venus 58) Auns Taurus 7 of Disks 20-25 Saturn Harahel 6) Valefar Duke Venus 59) Orias Taurus 25-30 Mizrael 42) Vepar Duke Venus 60) Napula Taurus 8 of 0-5 Gemini Jupiter Umabel 7) Amon Marquise Moon 61) Zagan Swords 5-10 Iahhel 43) Sabnock Marquise Moon 62) Valu Gemini 9 of 10-15 Mars Annauel 8) Barbatos Duke Venus 63) Andras Swords Gemini 15-20 Mekekiel 44) Shax Marquise Moon 64) Haures Gemini 10 of 20-25 Sun Damabiah 9) Paimon King Sun 65) Swords Gemini Andrealphus 25-30 Meniel 45) Vine King Sun 66) Cimeries Gemini Earl Mars 2 of Cups 0-5 Cancer Venus Eiael 10) Buer President Mercury 67) Amducias 5-10 Habuiah 46) Bifrons Earl Mars 68) Belial Cancer 3 of Cups 10-15 Mercury Rochel 11) Gusion Duke Venus 69) Cancer Decarabia 15-20 Libamiah 47) Vuall Duke Venus 70) Seer Cancer 4 of Cups 20-25 Moon Haiaiel 12) Sitri Prince Jupiter 71) Cancer Dantaylion 25-30 Mumiah 48) President