Indonesian Progressive Muslims and the Discourse of the Israeli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spencer Sunshine*

Journal of Social Justice, Vol. 9, 2019 (© 2019) ISSN: 2164-7100 Looking Left at Antisemitism Spencer Sunshine* The question of antisemitism inside of the Left—referred to as “left antisemitism”—is a stubborn and persistent problem. And while the Right exaggerates both its depth and scope, the Left has repeatedly refused to face the issue. It is entangled in scandals about antisemitism at an increasing rate. On the Western Left, some antisemitism manifests in the form of conspiracy theories, but there is also a hegemonic refusal to acknowledge antisemitism’s existence and presence. This, in turn, is part of a larger refusal to deal with Jewish issues in general, or to engage with the Jewish community as a real entity. Debates around left antisemitism have risen in tandem with the spread of anti-Zionism inside of the Left, especially since the Second Intifada. Anti-Zionism is not, by itself, antisemitism. One can call for the Right of Return, as well as dissolving Israel as a Jewish state, without being antisemitic. But there is a Venn diagram between anti- Zionism and antisemitism, and the overlap is both significant and has many shades of grey to it. One of the main reasons the Left can’t acknowledge problems with antisemitism is that Jews persistently trouble categories, and the Left would have to rethink many things—including how it approaches anti- imperialism, nationalism of the oppressed, anti-Zionism, identity politics, populism, conspiracy theories, and critiques of finance capital—if it was to truly struggle with the question. The Left understands that white supremacy isn’t just the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis, but that it is part of the fabric of society, and there is no shortcut to unstitching it. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh Department of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, New Cross, London SE14 6NW, UK The Working Papers Series is intended to initiate discussion, debate and discourse on a wide variety of issues as it pertains to the analysis of antisemitism, and to further the study of this subject matter. Please feel free to submit papers to the ISGAP working paper series. Contact the ISGAP Coordinator or the Editor of the Working Paper Series, Charles Asher Small. Working Paper Hirsh 2007 ISSN: 1940-610X © Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy ISGAP 165 East 56th Street, Second floor New York, NY 10022 United States Office Telephone: 212-230-1840 www.isgap.org ABSTRACT This paper aims to disentangle the difficult relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. On one side, antisemitism appears as a pressing contemporary problem, intimately connected to an intensification of hostility to Israel. Opposing accounts downplay the fact of antisemitism and tend to treat the charge as an instrumental attempt to de-legitimize criticism of Israel. I address the central relationship both conceptually and through a number of empirical case studies which lie in the disputed territory between criticism and demonization. The paper focuses on current debates in the British public sphere and in particular on the campaign to boycott Israeli academia. Sociologically the paper seeks to develop a cosmopolitan framework to confront the methodological nationalism of both Zionism and anti-Zionism. It does not assume that exaggerated hostility to Israel is caused by underlying antisemitism but it explores the possibility that antisemitism may be an effect even of some antiracist forms of anti- Zionism. -

Cool Trombone Lover

NOVEMBER 2013 - ISSUE 139 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM ROSWELL RUDD COOL TROMBONE LOVER MICHEL • DAVE • GEORGE • RELATIVE • EVENT CAMILO KING FREEMAN PITCH CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK CITY FEATURED ARTISTS / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm RESIDENCIES / 7:00, 9:00 & 10:30pm Fri & Sat, Nov 1 & 2 Wed, Nov 6 Sundays, Nov 3 & 17 GARY BARTZ QUARTET PLUS MICHAEL RODRIGUEZ QUINTET Michael Rodriguez (tp) ● Chris Cheek (ts) SaRon Crenshaw Band SPECIAL GUEST VINCENT HERRING Jeb Patton (p) ● Kiyoshi Kitagawa (b) Sundays, Nov 10 & 24 Gary Bartz (as) ● Vincent Herring (as) Obed Calvaire (d) Vivian Sessoms Sullivan Fortner (p) ● James King (b) ● Greg Bandy (d) Wed, Nov 13 Mondays, Nov 4 & 18 Fri & Sat, Nov 8 & 9 JACK WALRATH QUINTET Jason Marshall Big Band BILL STEWART QUARTET Jack Walrath (tp) ● Alex Foster (ts) Mondays, Nov 11 & 25 Chris Cheek (ts) ● Kevin Hays (p) George Burton (p) ● tba (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Captain Black Big Band Doug Weiss (b) ● Bill Stewart (d) Wed, Nov 20 Tuesdays, Nov 5, 12, 19, & 26 Fri & Sat, Nov 15 & 16 BOB SANDS QUARTET Mike LeDonne’s Groover Quartet “OUT AND ABOUT” CD RELEASE LOUIS HAYES Bob Sands (ts) ● Joel Weiskopf (p) Thursdays, Nov 7, 14, 21 & 28 & THE JAZZ COMMUNICATORS Gregg August (b) ● Donald Edwards (d) Gregory Generet Abraham Burton (ts) ● Steve Nelson (vibes) Kris Bowers (p) ● Dezron Douglas (b) ● Louis Hayes (d) Wed, Nov 27 RAY MARCHICA QUARTET LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES / 11:30 - Fri & Sat, Nov 22 & 23 FEATURING RODNEY JONES Mon The Smoke Jam Session Chase Baird (ts) ● Rodney Jones (guitar) CYRUS CHESTNUT TRIO Tue Cyrus Chestnut (p) ● Curtis Lundy (b) ● Victor Lewis (d) Mike LeDonne (organ) ● Ray Marchica (d) Milton Suggs Quartet Wed Brianna Thomas Quartet Fri & Sat, Nov 29 & 30 STEVE DAVIS SEXTET JAZZ BRUNCH / 11:30am, 1:00 & 2:30pm Thu Nickel and Dime OPS “THE MUSIC OF J.J. -

Contemporary Left Antisemitism

“David Hirsh is one of our bravest and most thoughtful scholar-activ- ists. In this excellent book of contemporary history and political argu- ment, he makes an unanswerable case for anti-anti-Semitism.” —Anthony Julius, Professor of Law and the Arts, UCL, and author of Trials of the Diaspora (OUP, 2010) “For more than a decade, David Hirsh has campaigned courageously against the all-too-prevalent demonisation of Israel as the one national- ism in the world that must not only be criticised but ruled altogether illegitimate. This intellectual disgrace arouses not only his indignation but his commitment to gather evidence and to reason about it with care. What he asks of his readers is an equal commitment to plumb how it has happened that, in a world full of criminality and massacre, it is obsessed with the fundamental wrongheadedness of one and only national movement: Zionism.” —Todd Gitlin, Professor of Journalism and Sociology, Columbia University, USA “David Hirsh writes as a sociologist, but much of the material in his fascinating book will be of great interest to people in other disciplines as well, including political philosophers. Having participated in quite a few of the events and debates which he recounts, Hirsh has done a commendable service by deftly highlighting an ugly vein of bigotry that disfigures some substantial portions of the political left in the UK and beyond.” —Matthew H. Kramer FBA, Professor of Legal & Political Philosophy, Cambridge University, UK “A fierce and brilliant rebuttal of one of the Left’s most pertinacious obsessions. What makes David Hirsh the perfect analyst of this disorder is his first-hand knowledge of the ideologies and dogmata that sustain it.” —Howard Jacobson, Novelist and Visiting Professor at New College of Humanities, London, UK “David Hirsh’s new book Contemporary Left Anti-Semitism is an impor- tant contribution to the literature on the longest hatred. -

The Final BBC Young Jazz Musician 2020

The Final BBC young jazz musician 2020 The Final The Band – Nikki Yeoh’s Infinitum Nikki Yeoh (piano), Michael Mondesir (bass) and Mark Mondesir (drums) Matt Carmichael Matt Carmichael: Hopeful Morning Saxophone Matt Carmichael: On the Gloaming Shore Matt Carmichael: Sognsvann Deschanel Gordon Kenny Garrett arr. Deschanel Gordon: Haynes Here Piano Deschanel Gordon: Awaiting Thelonious Monk: Round Midnight Alex Clarke Bernice Petkere: Lullaby of the Leaves Saxophone Dave Brubeck: In Your Own Sweet Way Alex Clarke: Before You Arrived INTERVAL Kielan Sheard Kielan Sheard: Worlds Collide Bass Kielan Sheard: Wilfred's Abode Oscar Pettiford: Blues in the Closet Ralph Porrett Billy Strayhorn arr. Ralph Porrett: Lotus Blossom Guitar John Coltrane arr. Ralph Porrett: Giant Steps John Parricelli: Scrim Boudleaux Bryant: Love Hurts JUDGING INTERVAL Xhosa Cole BBC Young Jazz Musician 2018 Saxophone Thelonious Monk: Played Twice Xhosa Cole: George F on my mind Announcement and presentation of BBC Young Jazz Musician 2020 2 BBC young jazz musician 2020 Television YolanDa Brown Double MOBO award winning YolanDa Brown is the premier female saxophonist in the UK, known for delicious fusion of reggae, jazz and soul. Her debut album, “April Showers May Flowers” was no.1 on the jazz charts, her sophomore album released in 2017 “Love Politics War” also went to no.1 in the UK jazz charts. YolanDa has toured with The Temptations, Jools Holland’s Rhythm and Blues Orchestra, Billy Ocean and collaborated with artists such as Snarky Puppy’s Bill Laurance, Kelly Jones from Stereophonics and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. A broadcaster too – working across TV and radio, including her eponymous series for CBeebies, "YolanDa’s Band Jam", which recently won the Royal Television Society Awards as Best Children’s Programme. -

The Left and Antisemitism: an Overview

The left and antisemitism: an overview This article is an updated and adapted version of a speech by Daniel Randall, a Workers’ Liberty member and trade union activist, first given in 2016. We include it here as a broad introduction and overview to the issues. A recording of the speech as originally delivered is available online at bit.ly/left-and-as. Antisemitism: a pseudo-emancipatory bigotry Antisemitism is an ancient prejudice, with deep roots in the origins of Christian culture, bound up both with the developing ideology of incipient Christianity as it broke from the Jewish establishment, and with the particular position in which Jews stood in relation to the development of capitalist modernity. As Hal Draper put it in his 1977 essay “Marx and the Economic-Jew Stereotype”: “Jews were forced into a lopsided economic structure by Christendom’s prohibition on their entrance into agriculture, guild occupations, and professions.” Antisemitism is generally understood as racist, or basically- racist, hostility to Jewish people. The Jewish population of the UK is small, between 250,000 and 300,000, so empirically, August Bebel, the leader of Germany’s revolutionary socialist party in the 1890s, antisemitism is not the cutting edge of racism in this country, denounced antisemitism as “the socialism of fools”. and it has been a long time since antisemitism was the key structuring aspect of right-wing chauvinist and nationalist be distinguished, from racism, has to do with the sort of ideologies in Britain, which now foreground a generic anti- imaginary of power, attributed to the Jews, Zionism, and Israel, immigrant and often anti-Muslim politics. -

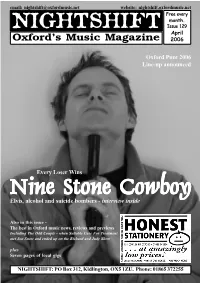

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 129 April Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 Oxford Punt 2006 Line-up announced Every Loser Wins NineNineNine StoneStoneStone CoCoCowbowbowboyyy Elvis, alcohol and suicide bombers - interview inside Also in this issue - The best in Oxford music news, reviews and previews Including The Odd Couple - when Suitable Case For Treatment met Jon Snow and ended up on the Richard and Judy Show plus Seven pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Harlette Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] PUNT LINE-UP ANNOUNCED The line-up for this year’s Oxford featured a sold-out show from Fell Punt has been finalised. The Punt, City Girl. now in its ninth year, is a one-night This years line up is: showcase of the best new unsigned BORDERS: Ally Craig and bands in Oxfordshire and takes Rebecca Mosley place on Wednesday 10th May. JONGLEURS: Witches, Xmas The event features nineteen acts Lights and The Keyboard Choir. across six venues in Oxford city THE PURPLE TURTLE: Mark and post-rock is featured across showcase of new musical talent in centre, starting at 6.15pm at Crozer, Dusty Sound System and what is one of the strongest Punt the county. In the meantime there Borders bookshop in Magdalen Where I’m Calling From. line-ups ever, showing the quality are a limited number of all-venue Street before heading off to THE CITY TAVERN: Shirley, of new music coming out of Oxford Punt Passes available, priced at £7, Jongleurs, The Purple Turtle, The Sow and The Joff Winks Band. -

Fall 2011 - Elul 5771 Your Invitation to Perform One More Act of Kindness Before the High Holy Days

xsrpvThe Orchard ® ® ® ® ® ® Published by The Jewish Federations of North America Rabbinic Cabinet FALL 2011 - ELUL 5771 YOUR INVITATION TO PERFORM ONE MORE ACT OF KINDNESS BEFORE THE HIGH HOLY DAYS. This Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, we’re not to help families get back on their feet. And it’ll asking you to make a resolution for next year, pay for other things you can’t put a price on. we’re asking you to do something meaningful Like connecting every generation to Israel and right now. Your donation will help pay for inspiring a lifelong passion for Jewish living. food, medicine and employment counseling Do a world of good. Make a world of difference. ® JewishFederations.org jfederations @jfederations Thexsrpv Orchard Chair A Prayer For Gilad Shalit’s Release ...............................................................................4 Rabbi Stuart Weinblatt The Jewish Federations of North America Rabbinic Cabinet ................................5 Vice Chairs From the JFNA Chair of the Board and President ...................................................6 Rabbi Les Bronstein Kathy Manning and Jerry Silverman Rabbi Fred Klein New Year’s Greeting from the Director of the Rabbinic Cabinet ........................7 Rabbi Larry Kotok Rabbi Gerald I. Weider Rabbi Steven Lindeman A Rosh Hashana Greeting .................................................................................................8 Rabbi Stuart Weinblatt President Rabbi Steven Foster High Holy Day Thoughts and Sermonic Contributions ............................................9 -

Downbeat.Com February 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 .K. U DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2011 DOWNBEAT BUNKY GREEN & RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA // OMAR SOSA // JOHN MCNEIL // KEVIN EUBANKS // JAZZ VENUE GUIDE FEBRUARY 2011 FEBRUARY 2011 VOLUME 78 – NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser Circulation Assistant Alyssa Beach ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

The Jazz Rag

THE JAZZ RAG ISSUE 135 WINTER 2015 UK £3.25 CONTENTS FESTIVALS 2015 JAZZ RAG'S PICK OF THE 2015 JAZZ FESTIVALS (PAGES 18-21) PEPPER OF PEPPER AND THE JELLIES PHOTOGRAPHED BY MERLIN DALEMAN AT THE 2014 BIRMINGHAM JAZZ AND BLUES FESTIVAL. THE ITALIAN GROUP IS DUE TO RETURN TO BIRMINGHAM THIS YEAR. 4 NEWS 6 UPCOMING EVENTS 8 DIGBY'S HALF DOZEN AT 20 10 VIC ASH (1930-2014) 11 MIKE BURNEY REMEMBERED 12 2014'S TOP TRUMPET: SUBSCRIBE TO THE JAZZ RAG STEVE WATERMAN THE NEXT SIX EDITIONS MAILED 14 BERNARD 'ACKER' BILK (1929-2014) DIRECT TO YOUR DOOR FOR ONLY A LIFE IN PHOTOGRAPHS £17.50* Simply send us your name. address and postcode along with your 16 HAPPY 100TH BIRTHDAY TO THE payment and we’ll commence the service from the next issue. JAZZ KIDS OF 1915 OTHER SUBSCRIPTION RATES: SCOTT YANOW CUTS THE CAKE FOR EU £20.50 USA, CANADA, AUSTRALIA £24.50 BILLIE, FRANK AND THE REST Cheques / Postal orders payable to BIG BEAR MUSIC 22 CD REVIEWS Please send to: JAZZ RAG SUBSCRIPTIONS PO BOX 944 | Birmingham | England 32 BEGINNING TO CD LIGHT * to any UK address THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 NOW LISTEN TO JAZZ RAG! Fax: 0121 454 9996 London’s first internet jazz radio station jazzlondonradio.com covers a wide range Email: [email protected] of music, with extended programmes of both classic and contemporary jazz every Web: www.jazzrag.com afternoon. Former Director of Jazz Services Chris Hodgkins is the presenter of Jazz Then and Now on Mondays and Wednesdays at 3.00 pm and 8.00 pm. -

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism

Anti‐Zionism and Antisemitism: Cosmopolitan Reflections David Hirsh* INTRODUCTION 1. The research question Most accounts that understand antisemitism to be a pressing or increasing phenom‐ enon in contemporary Europe rely on the premise that this is connected to a rise in anti‐Zionism. Theorists of a ‘new antisemitism’ often understand anti‐Zionism to be a new form of appearance of an underlying antisemitism. On the other side, sceptics understand antiracist anti‐Zionism to be entirely distinct from antisemitism and they often understand efforts to bring the two phenomena together as a political dis‐ course intended to delegitimize criticism of Israeli policy. The project of this work is to investigate the relationship between antisemitism and anti‐Zionism, since under‐ standing this central relationship is an important part of understanding contemporary antisemitism. The hypothesis that this work takes seriously is the suggestion that, if an anti‐ Zionist world view becomes widespread, then one likely outcome is the emergence of openly antisemitic movements. The proposition is not that anti‐Zionism is motivated by antisemitism; rather that anti‐Zionism, which does not start as anti‐ semitism, normalizes hostility to Israel and then to Jews. It is this hostility to Israel and then to Jews, a hostility which gains some of its strength from justified anger with Israeli human rights abuses, that is on the verge of becoming something that many people now find understandable, even respectable. It is moving into the main‐ stream. An understanding of the rhetoric and practice of antiracist anti‐Zionism as a form of appearance of a timeless antisemitism tends to focus attention on motiva‐ tion. -

Genesis and Prospect of the Palestine-Israel Conflict: from the Jewish Question in Europe to the Jewish State in Palestine and the Jewish Lobby in America

Book Draft in Progress Genesis and Prospect of the Palestine-Israel Conflict: From the Jewish Question in Europe to the Jewish State in Palestine and the Jewish Lobby in America Dr. Mohamed Elmey Elyassini U.S. Fulbright Scholar 2011-2012 Associate Professor of Geography Department of Earth & Environmental Systems Indiana State University, Terre Haute, Indiana, USA Email: [email protected] URL: https://www.indstate.edu/cas/faculty/melyassini 1 Book Draft in Progress To all dead, living, and unborn victims of Zionism and the State of Israel 2 Book Draft in Progress Table of Contents Acknowledgments Preface The Jewish Question in Europe 1. Introduction to the Jewish Question 2. The Non-Jewish Origin of Zionism 3. The Non-Herzlian Genesis of Herzlian Zionism The Jewish State in Palestine 4. The Non-Semitic Origins of Contemporary Jews 5. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Jewish Settlers since 1948 6. The Non-Zionist Future of Palestine The Jewish Lobby in America 7. What is the Jewish Lobby in the United States? 8. Branches of the Jewish Lobby in the United States 9. The Jewish Lobby at Work 10. Why Does America Support Israeli Jews who do not believe in Jesus against Palestinian Muslims and Christians who do believe in Jesus? Endnotes Chronology of Key Dates Maps Bibliography Index 3 Book Draft in Progress Acknowledgements While the acknowledgements section of a book praises the efforts of those who contributed to the work, it sometimes ought to denounce the efforts of those who tried to undermine the work. The central argument of this book was outlined in six conference presentations to the annual meetings of the Association of American Geographers (AAG) between 2002 and 2008.