Nerve Damage Following Central Neuraxial Blockade: Is It Avoidable?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Use of Remifentanil As the Primary Agent for Analgesia in Parturients

The Use Of Remifentanil As The Primary Agent For Analgesia In Parturients Author: Bryan Clifford Anderson, DNAP, CRNA Learning Objectives for this Self Study: The Importance of Exploring Remifentanil as an Upon completion of this study, the CRNA will be able to: Option for Treating Labor Pain The use of remifentanil in the parturient as the primary analgesic is 1. Discuss the significance of remifentanil use as a primary analgesic significant for several reasons; the most salient of which is the basic human agent in parturients for whom neuraxial anesthesia is not an option. right to the management of pain. Pain, as defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), is “an unpleasant sensory and 2. Identify clients in which neuraxial anesthesia might be contraindicated. emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.” 2 Labor is a cause of severe pain for many women and is a problem that should 3. Compare the efficacy of select medications in the control of pain be addressed and managed in accordance with the needs and wishes of the in paturients. individual patient. Interventions that alleviate or eliminate pain are not merely a matter of beneficence, but also form part of the duty to prevent harm.3 4. Appraise findings in current evidence to determine to what extent The variations in pain perception among women in labor creates an essential remifentamil is a viable option for pain management in parturient patients. component in the administration of anesthesia in the provision of patient- centered anesthesia care. One recent study identifies that the perception of 5. -

Pediatric Neuraxial Blockade

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine Publications Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine 1993-7 Pediatric neuraxial blockade John Pullerits University of Massachusetts Medical School Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/anesthesiology_pubs Part of the Anesthesiology Commons Repository Citation Pullerits J, Holzman RS. (1993). Pediatric neuraxial blockade. Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine Publications. https://doi.org/10.1016/0952-8180(93)90131-W. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/anesthesiology_pubs/82 This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine Publications by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pediatric Neuraxial Blockade John Pullerits, MD, FRCPC,* Robert S. Holzman, MD? Department of Anesthesiology, University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, MA, and Department of Anesthesia, Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA. Regional anesthetic techniques for children have recently enjoyed Historical Perspective a justified resurgence in popularity. Intraoperative blockade of August Bier’s investigation of spinal anesthesia in Ger- the neuraxis, whether by the spinal or epidural route, provides many’ and Siccard’s* and Cathelin’$ studies of caudal excellent analgesia with minimal physiologic -

SOAP Thrombocytopenia Consensus Statement FINAL

The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology Interdisciplinary Consensus Statement on Neuraxial Procedures in Obstetric Patients with Thrombocytopenia Melissa E. Bauer DO1, Katherine Arendt MD2, Yaakov Beilin MD3, Terry Gernsheimer MD4, Juliana Perez Botero MD5, Andra H. James MD6, Edward Yaghmour MD7, Roulhac D. Toledano MD, PhD8, Mark Turrentine MD9, Timothy Houle PhD10, Mark MacEachern MLIS11, Hannah Madden, BS10, Anita Rajasekhar, MD MS12, Scott Segal MD13, Christopher Wu MD14, Jason P. Cooper MD, PhD4, Ruth Landau MD15, Lisa Leffert, MD10 1Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan 2Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Mayo-Clinic 3Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, and Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai 4Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine 5Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin and Versiti 6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Duke University 7Department of Anesthesiology, Vanderbilt University 8Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Care, and Pain Medicine, NYU Langone Health 9Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine. Liaison for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 10Department of Anesthesiology, Massachusetts General Hospital 11Taubman Health Sciences Library, University of Michigan 2 12Department of Medicine, University of Florida 13Department of Anesthesiology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine 14Department -

Assessment of Neuraxial Blockade Level Differential Blockade Occurs Due to Anatomy and the Mechanism of Action of Local Anesthetics

Dermatome Levels This is the most common anatomical configuration. Variation may occur among patients. Assessment of Neuraxial Blockade Level Differential blockade occurs due to anatomy and the mechanism of action of local anesthetics. Local anesthetics injected into the subarachnoid/epidural space block transmission at spinal nerve roots. Blockade of nerve transmission is dependent on the concentration that reaches the site of action and the duration of contact. As local anesthetic spreads and distance increases, a smaller concentration of local anesthetic is available to reach nerve roots. Spinal nerve roots contain several nerve fiber types. In general, small myelinated fibers are more susceptible to blockade than larger unmyelinated fibers. With a neuraxial block there is a difference between sympathetic, sensory, and motor block level. The sympathetic level is generally two to six dermatome levels higher than the sensory level. The sensory level is approximately two dermatome levels higher than the motor level. Knowledge of key dermatome levels assists the anesthesia provider in assessing the level of neuraxial blockade. An alcohol wipe is useful to assess the level of sympathectomy by measuring the patients’ ability to perceive skin temperature sensation. A blunt needle is useful in the assessment of the sensory level. It should be sharp enough to cause a “pin prick” sensation but not so sharp as to break the patients skin. The use of the spinal needle stylet can be used. Pinching the patient can also be used. The table below will help determine if the level of blockade achieves the minimum level required for a proposed surgical procedure. When reviewing the required sensory levels, it seems odd that the sensory level is higher than where the surgical procedure actually takes place. -

Anesthesia: Essays and (KSA) for Entire Editorial Board Visit : Researches

A E R Editor‑in‑Chief : Open Access Mohamad Said Maani Takrouri HTML Format Anesthesia: Essays and (KSA) For entire Editorial Board visit : http://www.aeronline.org/editorialboard.asp Researches Original Article Efficacy of intrathecal midazolam in potentiating the analgesic effect of intrathecal fentanyl in patients undergoing lower limb surgery Anshu Gupta, Hemlata Kamat1, Utpala Kharod1 Departments of Anaesthesia, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, 1Pramukhswami Medical College, Anand, Gujarat, India Corresponding author: Dr. Anshu Gupta, Department of Anaesthesia, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India. E‑mail: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The intrathecal administration of combination of drugs has a synergistic effect on the subarachnoid block characteristics. This study was designed to study the efficacy of intrathecal midazolam in potentiating the analgesic duration of fentanyl along with prolonged sensorimotor blockade. Materials and Methods: In a double‑blind study design, 75 adult patients were randomly divided into three groups: Group B, 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine; Group BF, 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine + 25 mcg of fentanyl; and Group BFM, 3 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine + 25 mcg of fentanyl + 1 mg of midazolam. Postoperative analgesia was assessed using visual analog scale scores and onset and duration of sensory and the motor blockade was recorded. Results: Mean duration of analgesia in Group B was 211.60 ± 16.12 min, in Group BF 420.80 ± 32.39 min and in Group BFM, it was 470.68 ± 37.51 min. There was statistically significant difference in duration of analgesia between Group B and BF ( P = 0.000), between Group B and BFM (P = 0.000), and between Group BF and BFM (P = 0.000). -

Complications of Neuraxial Blockade

Complications of Neuraxial Blockade Several complications are associated with neuraxial blockade. Complications can be divided into several categories and include: exaggerated physiological responses, needle/catheter placement, and medication toxicity. Overall there is a low incidence of serious complications related to the administration of neuraxial blockade. However, complications may be temporary or permanent. Use of epidural anesthesia may have a higher incidence of complications when compared to spinal anesthesia. The patient population most affected is obstetrics. Adverse or Exaggerated Physiological Responses This category includes high neural blockade, cardiac arrest, and urinary retention. As noted earlier, there are normal physiologic manifestations that occur with neuraxial blockade. Vigilance, knowledge, preparation, and anticipation can reduce complications. High Neural Blockade High neural blockade can occur with either epidural or spinal anesthesia. This complication may be due to the administration of excessive doses of local anesthetic, failure to reduce doses in patients susceptible to excessive spread (i.e. elderly, pregnant, obese, or short patients), increased sensitivity, and excessive spread. When dosing a spinal or epidural, it is important to monitor the patients’ vital signs and block level. Use of alcohol wipes as well as pin prick testing every few minutes will help track the blocks progression. Incremental dosing of epidurals allows the anesthesia provider to determine if the block is progressing more rapidly than anticipated. With hyperbaric spinal techniques, changing the patients’ position may slow down excessive spread. Prevention is based on careful consideration in the dosing of the neuraxial block, anticipation of potential complications, and continual monitoring of the blocks progression. Initial symptoms include the following: dyspnea numbness or weakness of the upper extremities (i.e. -

Regional Anesthesia in Children; Beyond the Caudal Block

Regional Anesthesia in Children; Beyond the Caudal Block Santhanam Suresh, MD FAAP Attending Anesthesiologist Co-Director, Pain Treatment Services Children’s Memorial Hospital Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine Chicago, IL Introduction: Regional anesthesia is becoming more popular in children because of its benefits for the patient in the postoperative period.(1) As we increase our understanding of local anesthetic pharmacology and toxicity, we have expanded our capability of safely providing a new level of postanesthesia pain and comfort. The two main types of regional anesthesia used in children are central neuraxial blocks and peripheral nerve blocks. Local Anesthetics: Choice and Dosage Bupivacaine and ropivacaine are two commonly used amide local anesthetics in pediatric patients. Dosing is based on weight and age of the patient. Potential toxicity from single doses of local anesthetics should be avoided by calculating doses on a mg/kg basis and should not be extrapolated from adult experiences using predetermined volumes of local anesthetic for regional blocks. We use a concentration of 0.25% bupivacaine for peripheral nerve blocks and 0.1% bupivacaine for continuous central neuraxial infusions. When a continuous infusion is utilized, care has to be taken not to exceed toxic doses for children. For instance, bupivacaine infusion should not exceed 0.2 mg/kg/hr in neonates and 0.4 mg/kg/hr in older children.(2) Care has to be taken to avoid intravascular injections since cardiac toxicity from longer acting drugs like bupivacaine can be fatal. Newer isomers including levobupivacine may potentially reduce the potential toxicity to the cardiac and central nervous system.(3) Ropivacaine is a newer amide local anesthetic that has a higher threshold for cardiac and neurological toxicity than bupivacaine.(4) A 0.2% solution is commonly used and the volume of drug injected is 1 mL/kg to a maximum dose of 20 mL. -

Dr. Ajaykumar Anandan Dr. Juvairiya Banu* Original Research Paper

Original Research Paper Volume-9 | Issue-12 | December - 2019 | PRINT ISSN No. 2249 - 555X | DOI : 10.36106/ijar Anaesthesiology A COMPARISON OF IV DEXMEDETOMIDINE AND MIDAZOLAM FOR SEDATION IN PATIENTS UNDER NEURAXIAL ANAESTHESIA Dr. Ajaykumar MD, Professor, Department Of Anesthesiology, Pain Medicine And Critical Care, Sree Anandan Balaji Medical College And Hospital, Biher, Chennai. Dr. Juvairiya Junior Resident, Department Of Anesthesiology, Pain Medicine And Critical Care, Sree Banu* Balaji Medical College And Hospital, Biher, Chennai. *Corresponding Authour ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: Spinal anesthesia is the most widely practiced method of anesthetizing a patient for majority of the infraumbilical surgeries. Several drugs have been used as an adjuvant to prolong the intrathecal block which can be given either intrathecally or intravenously. This study aims at comparing the efcacy of iv dexmedetomidine and midazolam for sedation for patients under neuraxial anesthesia. MATERIALS AND METHODS: It was a randomized study. 60 patients were enrolled in this study of either sex age group between and American society of Anesthesiology(ASA) physical satus I, II&III Study was conducted after getting informed and written consent. Patients were divided into two groups GROUP D(iv dexmedetomidine) and GROUP M(iv midazolam). Various parameters like HR, MAP, were recorded. Sedation score was recoded using ramsay sedation score 10 minutes, 15 minutes, 20 minutes, 35 minutes, 50 minutes, 65 minutes & 80 minutes. RESULTS: Among the cases, with respect to the Ramsay Sedation Score, both the groups were statistically comparable and were statistically signicant (P < 0.05) after 10 minutes, 15 minutes, 20 minutes, 35 minutes, 50 minutes, 65 minutes & 80 minutes. -

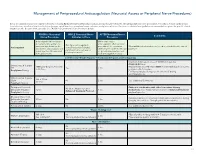

Neuraxial Access Or Peripheral Nerve Procedures)

Management of Periprocedural Anticoagulation (Neuraxial Access or Peripheral Nerve Procedures) Below are guidelines to prevent spinal hematoma following Epidural/Intrathecal/Spinal procedures and perineural hematoma following peripheral nerve procedures. Procedures include epidural injec- tions/infusions, intrathecal injections/infusions/pumps, spinal injections, peripheral nerve catheters, and plexus infusions. Decisions to deviate from guideline recommendations given the specific clinical situation are the decision of the provider. See ‘Additional Comments’ section for more details. PRIOR to Neuraxial/ WHILE Neuraxial/Nerve AFTER Neuraxial/Nerve Comments Nerve Procedure Catheter in Place Procedure How long should I hold prior When can I restart to neuraxial procedure? (i.e. anticoagulants after neuraxial Can I give anticoagulants minimum time between the procedures? (i.e. minimum What additional information do I need to consider for the care of Anticoagulant concurrently with neuraxial, last dose of anticoagulant and time between catheter removal patients? peripheral nerve catheter, or spinal injection OR neuraxial/ or spinal/nerve injection and plexus placement? nerve placement) next anticoagulation dose) Low-Molecular Weight Heparin, Unfractionated Heparin, and Fondaparinux Maximum total heparin dose of 10,000 units per day (5000 SQ Q12 hrs) Unfractionated Heparin 5000 units Q 12 hrs – no time Heparin 5000 units SQ 8 hrs is NOT recommended with concurrent SQ Yes 2 hrs restrictions neuraxial catheter in place Prophylaxis Dosing For IV prophylactic dosing, use ‘treatment’ IV dosing recommendations. Unfractionated Heparin SQ: 8-10 hrs SQ/IV No 2 hrs See ‘Additional Comments’ IV: 4 hrs Treatment Dosing Enoxaparin (Lovenox), Caution in combination with other hemostasis-altering No (Note: May be used for Dalteparin (Fragmin) 12 hrs 4 hrs medications. -

Call for Editorial Board Members As You Are

CallforEditorialBoardMembers Asyouarewellawarethatweareamedicalandhealthsciencespublishers; publishingpeer-reviewedjournalsandbookssince2004. Wearealwayslookingfordedicatededitorialboardmembersforour journals.Ifyoucompletedyourmasterdegreeandmusthaveatleast fiveyearsexperienceinteachingandhavinggoodpublicationrecordsin journalsandbooks. Ifyouareinterestedtobeaneditorialboardmemberofthejournal;please provideyourcompleteresumeandaffiliationthroughe-mail(i.e.info@ rfppl.co.in)orvisitourwebsite(i.e.www.rfppl.co.in)toregisteryourself online. CallforPublicationof ConferencePapers/Abstracts Wepublishpre-conference orpost-conference papers and abstracts in ourjournals,anddeliverhardcopyandgivingonlineaccessinatimely fashiontotheauthors. Formoreinformation,pleasecontact: Formoreinformation,pleasecontact: ALal Publication–in-charge RedFlowerPublicationPvt.Ltd. 48/41-42,DSIDC,Pocket-II MayurViharPhase-I Delhi–110091(India) Phone:91-11-22754205,45796900 E-mail:[email protected] IJAA/Volume6Number5(Part-I)/Sep-Oct2019 FreeAnnouncementsofyour Conferences/Workshops/CMEs ThisprivilegetoallIndianandothercountriesconferencesorganizing committeememberstopublishfreeannouncementsofyourconferences/ workshops. If you are interested, please send your matter in word formatsandimagesorpicturesinJPG/JPEG/Tiffformatsthroughe-mail [email protected]. Terms&Conditionstopublishfreeannouncements: 1. Onlyconferenceorganizersareeligibleuptoonefullblackand whitepage,butnotapplicableforthefront,insidefront,inside backandbackcover,however,thesepagesarepaid. 2. -

Management of Total Spinal Block in Obstetrics

Management of total spinal block in obstetrics Shiny Sivanandan* and Anoop Surendran *Correspondence email: [email protected] doi: 10.1029/WFSA-D-18-00034 Summary Total spinal or a high neuraxial blockade is a recognised complication of central neuraxial techniques. A high Clinical Articles number of incidents of a high neuraxial block are being reported in obstetrics following the increased use of neuraxial anaesthesia. Unrecognised subdural or intrathecal placement of an epidural catheter and an intended spinal technique after a failed epidural analgesia are two main identified causes of high spinal block in obstetrics. The anaesthetist performing these procedures must be aware of this serious complication and must remain vigilant throughout. One should have a high level of suspicion of a high spinal while giving a test dose or topping up an epidural in the delivery suite or in the theatre especially if there is a rapid development of sensory and motor block within minutes. Key words: total spinal block; high neuraxial blockade; unrecognised subdural catheter; intrathecal catheter; maternal cardiac arrest INTRODUCTION Total spinal or a high neuraxial blockade is a recognised obstetric anaesthesia is not known. Estimates vary complication of central neuraxial techniques that between 1:2,9714 and 1:16,2005 anaesthetics. include spinal and epidural anaesthesia. A high number of incidents of a high neuraxial block are AETIOLOGY being reported in obstetrics following the increased Dosage - An accurate estimation of the required dosage use of neuraxial anaesthesia. The leading cause of of local anaesthetic (LA) to achieve an appropriate maternal death in the UK during or up to six weeks level of intrathecal anaesthesia is difficult and we rely after the end of pregnancy is due to thrombosis and on factors such as nature of surgery, patient anatomy thromboembolism.1 But high neuraxial block is now and technique of injection. -

2015 PG Dissertation Topics.Pdf

Dr.NTR UNIVERSITY of HEALTH SCIENCES DISSERTATION TOPICS Sl. Year SPL No. TITLE OF DISSERTATION SPECIALITY 1 Comparative Study Of 0.5% Levobupivacaine Versus 0.75% Ropivacaine In Subarachnoid Block. 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY 2 Comparative Study Of Dexmedetomidine Versus Fentanyl With Midazolam In Attenuation Of 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY Pressor Response During Laryngoscopy And Intubation. 3 A Comparative Study Of Intrathecal Isobaric 0.75% Ropivacaine And Hyperbaric 0.5% 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY Bupivacaine For Elective Caesarean Section. 4 Comparative Study Of Epidural 0.125% Bupivacaine (9 Ml) With 150 Mcg Clonidine (1 Ml) Versus 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY Epidural 0.125% Bupivacaine (10Ml) For Post Operative Annalgesia. 5 Comparative Study Of Effectiveness Of Epidural Labour Analgesia For Vaginal Delivery With 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY 0.125% Levobupivacaine Versus 0.125% Racemic Bupivacaine. 6 Comparative Study Of 0.5% Levobupi Vacaine Versus 0.5% Racemic Bupivacaine In 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY Subarachanoid Block. 7 A Comparative Study Of Ondansetron And Dexamethasone With Ondansetron Alone In 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY Prevention Of Postoperative Nausea And Vomiting (Ponv) In Laparoscopic Surgeries Under General Anaesthesia 8 Evaluation Of Efficacy Of Intravenous Magnesium Sulphate On Postoperative Analgesia For 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY Operations Done Under General Anaesthesia 9 A Comparative Study Between Epidural Bupivacaine With Buprenorphine And Epidural 2015 MD ANAESTHESIOLOGY Bupivacaine For Postoperative Analgesia In Abnominal And Lower