Musical Incarnations of Simon Templar Brigitte Doss-Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

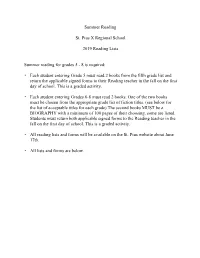

Summer Reading St. Pius X Regional School 2019 Reading Lists Summer Reading for Grades 5

Summer Reading St. Pius X Regional School 2019 Reading Lists Summer reading for grades 5 - 8 is required: ▪ Each student entering Grade 5 must read 2 books from the fifth grade list and return the applicable signed forms to their Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. This is a graded activity. ▪ Each student entering Grades 6-8 must read 2 books. One of the two books must be chosen from the appropriate grade list of fiction titles. (see below for the list of acceptable titles for each grade) The second books MUST be a BIOGRAPHY with a minimum of 100 pages of their choosing, some are listed. Students must return both applicable signed forms to the Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. This is a graded activity. ▪ All reading lists and forms will be available on the St. Pius website about June 17th. ▪ All lists and forms are below. ST. PIUS X - SUMMER READING Incoming Grade 8 (2019) 1. Each student entering Grade 8 must read 2 books. One of the two books must be chosen from the appropriate grade list of fiction titles. (see below for the list of acceptable titles for 8th grade) 2. The second books MUST be a BIOGRAPHY with a minimum of 100 pages of their choosing, some are listed. 3. Students must return the applicable signed forms (one form for the fiction title and one form for the biography title) to the Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. (both forms are below) 4. -

SJU Semester Abroad Policy

Saint Joseph's University Semester Abroad Policy Please be advised that starting with the fall 2003 semester, the following policy will be in effect for Saint Joseph’s University students who wish to study abroad and receive credit toward their Saint Joseph’s degree. Under this policy, students will remain registered at SJU and pay SJU full-time, day tuition plus a $100 Continuing Registration Fee for each semester they will be studying abroad. Students will be considered enrolled at Saint Joseph’s University while abroad and will be allowed to receive his/her entire financial aid package. Saint Joseph’s University will then pay the overseas program for the tuition portion of the program. Students will be responsible for all non-tuition fees associated with the program they will be attending. Please note that for some Saint Joseph’s University affiliated programs, students may be required to pay other fees to Saint Joseph’s University first and Saint Joseph’s University will then forward these fees to the program sponsor. Students must receive proper approval for their proposed program of study. Upon successful completion of an approved foreign program of study, credit will be granted towards graduation for all appropriate courses taken on SJU approved programs. APPLICATION PROCESS Students must apply through and receive approval from the Center for International Programs (CIP) in order to study abroad. The on-line application cycle for the fall term typically opens in January and closes in mid- February or on March 1st (depending on the program). The on-line application cycle for the spring term typically opens in late-August and closes in mid-September or on October 1st (again, depending on the program). -

Desert Island Times 18

D E S E RT I S L A N D T I M E S S h a r i n g f e l l o w s h i p i n NEWPORT SE WALES U3A No.18 17th July 2020 Commercial Street, c1965 A miscellany of Contributions from OUR members 1 U3A Bake Off by Mike Brown Having more time on my hands recently I thought, as well as baking bread, I would add cake-making to my C.V. Here is a Bara Brith type recipe that is so simple to make and it's so much my type of cake that I don't think I'll bother buying one again. (And the quantities to use are in 'old money'!!) "CUP OF TEA CAKE" Ingredients 8oz mixed fruit Half a pint of cooled strong tea Handful of dried mixed peel 8oz self-raising flour # 4oz granulated sugar 1 small egg # Tesco only had wholemeal SR flour (not to be confused � with self-isolating flour - spell checker problem there! which of course means "No Flour At All!”) but the wholemeal only enhanced the taste and made it quite rustic. In a large bowl mix together the mixed fruit, mixed peel and sugar. Pour over the tea, cover and leave overnight to soak in the fridge. Next day preheat oven to 160°C/145°C fan/Gas Mark 4. Stir the mixture thoroughly before adding the flour a bit at a time, then mix in the beaten egg and stir well. Grease a 2lb/7" loaf tin and pour in the mixture. -

The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Online

Ch0XW [Mobile pdf] The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Online [Ch0XW.ebook] The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Pdf Free Leslie Charteris ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2154235 in Books 2014-06-24 2014-06-24Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x 1.00 x 5.50l, .0 #File Name: 1477843078256 pages | File size: 54.Mb Leslie Charteris : The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. What a Fabulous Adventure!By Carol KiekowThis book is another entertaining adventure of The Saint. I was on the edge of my seat throughout. I heartily recommend it!0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Good "Saint" storyBy Carolyn GravesGood "Saint" story. Location as much a character as the people. Kept my interest and kept me guessing throughout.4 of 13 people found the following review helpful. Super ReaderBy averageSimon Templar is in France, and has an incident on the road with a young woman. He ends up at a small local vineyard that is in financial trouble. The girl, Mimette requests his help. There is a family struggle over the place, and an uncle trying to find an old obscure Templar treasure on the property.Violence ensues, and the treasure is not what anyone thinks. Simon Templar is taking a leisurely drive though the French countryside when he picks up a couple of hitchhikers who are going to work at Chateau Ingare, a small vineyard on the site of a former stronghold of the Knights Templar. -

In Church on Bigfeasts. I Think

297 think it would be advisable to have them in church on big feasts. I think that, by making the establishment right after the mission that the Bishop ofBeauvais wants to have given there, it will be easy to get all that can be desiredfor the good of the confraternity. I have not done anything at all about suggesting this collection. Addressed: Monsieur Vincent 207. - TO CLEMENT DE BONZI, BISHOP OF BEZIERS [September or October 1635] 1 Your Excellency, I learned from M. Cassan, the brother of a priest from your town of Beziers, that you wanted to know three things about us. Now, since I was unable to have the honor of answering you at that time because I was leaving for the country, I decided to do so now. I shall tell you, first of all, Your Excellency, that we are entirely under the authority of the bishops to go to any place in their diocese they wish to send us to preach, catechize, and hear the general confessions of the poor; ten to fifteen days before ordina- tion, to teach all about mental prayer, practical and necessary theology, and the ceremonies of the Church to those about to be ordained; and to receive the latter into our house, after they are priests, for the purpose of renewing the fervor OurLord has given them at ordination. In a word, we are like the servants of the centurion in the Gospel2 with regard to the bishops, insofar as when they say to us: go, we are obliged to go; if they say: come, we are obliged to come; do that, and we are obliged to do it. -

Read Book the Saint Returns

THE SAINT RETURNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Leslie Charteris | 212 pages | 24 Jun 2014 | Amazon Publishing | 9781477842980 | English | Seattle, United States The Saint Returns PDF Book Create outlines for what you want to be accomplished. This was scrapped, and Ian Ogilvy took over the halo for 24 episodes as Simon Templar. This amount is subject to change until you make payment. He also somewhat deplored the tendency for the Saint to be seen primarily as a detective, and this was even stated in some of the later stories, e. Reading about Charteris' "amiable rascal" is infinitely easier and much more relaxing than writing more stories about my own fictitious rascal, Misfit Lil whom I like to think shares a trait or two with Mr Simon Templar! Honestly it was probably the highlight of an episode that mostly spun its wheels. Alyssa Milano legs boots feet Chad Allen magazine pin up clipping. Balthazar Getty Alyssa Milano magazine clipping pin up s vintage. He steals from rich criminals and keeps the loot for himself usually in such a way as to put the rich criminals behind bars. He threatens the biggest explosion of all unless sculptress Lynn Jackson is Hell In order for Eugene and Hitler to get out of hell, Eugene has to overcome the thing that has been keeping him in Hell. Simon Templar 24 episodes, The Saint also ventured into the comics section of our newspapers, battling alongside Dick Tracy and the other Sunday heroes. Seller's other items. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. -

Printable Schedule

Schedule for 9/29/21 to 10/6/21 (Central Time) WEDNESDAY 9/29/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 4:30am Fractured Flickers (1963) Comedy Featuring: Hans Conried, Gypsy Rose Lee THURSDAY 9/30/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 5:00am Backlash (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Jean Rogers, Richard Travis, Larry J. Blake, John Eldredge, Leonard Strong, Douglas Fowley 6:25am House of Strangers (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Edward G. Robinson, Susan Hayward, Richard Conte, Luther Adler, Paul Valentine, Efrem Zimbalist Jr. 8:35am Born to Kill (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Claire Trevor, Lawrence Tierney 10:35am The Power of the Whistler (1945) Film-Noir Featuring: Richard Dix, Janis Carter 12:00pm The Burglar (1957) Film-Noir Featuring: Dan Duryea, Jayne Mansfield, Martha Vickers 2:05pm The Lady from Shanghai (1947) Film-Noir Featuring: Orson Welles, Rita Hayworth, Everett Sloane, Carl Frank, Ted de Corsia 4:00pm Bodyguard (1948) Film-Noir Featuring: Lawrence Tierney, Priscilla Lane 5:20pm Walk the Dark Street (1956) Film-Noir Featuring: Chuck Connors, Don Ross 7:00pm Gun Crazy (1950) Film-Noir Featuring: John Dall, Peggy Cummins 8:55pm The Clay Pigeon (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Barbara Hale 10:15pm Daisy Kenyon (1947) Romance Featuring: Joan Crawford, Henry Fonda, Dana Andrews, Ruth Warrick, Martha Stewart 12:25am This Woman Is Dangerous (1952) Film-Noir Featuring: Joan Crawford, Dennis Morgan 2:30am Impact (1949) Film-Noir Featuring: Brian Donlevy, Raines Ella FRIDAY 10/1/21 TIME TITLE GENRE 5:00am Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) Thriller Featuring: Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins -

DINNERS ENROLL TOM SAWYER.’ at 2:40

1 11 T 1 Another Film for Film Fans to Suggest Gordon tried out in the drama, "Ch.!« There Is dren of Darkness.” It was thought No ‘Cimarron’ Team. Janet’s Next Role. in Theaters This Week the play would be a failure, so they Photoplays Washington IRENE DUNNE and ^ Wesley Ruggles, of the Nation will * fyJOVIE-GOERS prepared to abandon It. A new man- who as star and director made be asked to suggest the sort of agement took over the property, as- WEEK OP JUNE 12 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY cinematic history in 1931 In “Cimar- Stopping picture In which little Janet Kay signed Basil Sydney and Mary Ellis "Bit Town Olrl." "Manneouln." "Manneouln." are to be "Naughty Marietta" "Haughty Marietta" "Thank You. Ur. ron," reunited as star and Chapman. 4-year-old star dis- to the leads and Academy "alfm*83ifl£L'‘ Jon Hall in Will Rogers in Will Rosen in and ‘•The Shadow of and "The Shadow of Moto.” and "Ride. recently they scored a Broad- " director of a Paramount to Sth »nd O Sts. B.E, "The Hu-rlcane." "The Hurricane." _"David Harum "David Harum."_Silk Lennox."_ Silk Lennox." Ranter. Ride." picture covered by a Warner scout, should be way hit. This Lad in } into in the Rudy Vailee Rudy Valle? in Rudy Vallee in Myrna Loy. Clark Oa- Myrna Loy. Clark Oa- Loretta Yoon* in go production early fall. next seen on the screen. Miss So It Is at this time of Ambassador •■Sm* "Gold Diggers in "Gold Diggers in "Oold in ble and ble Chap- only yea# DuE*niBin Diggers Spencer Tracy and Spencer Tracy "Four Men and a The announcement was made after man the 18th «nd OolumblA Rd. -

Township Burnett Thanks Commission for Handling

RARITAN MOST PROGRESSIVE TOWNSHIP WITH THE SUBURBAN NEWSPAPER LARGEST IN GUARANTEED THIS AREA CIRCULATION "The Voice of the Raritan Bay District" VOL. IV.—No. 11. FORDS AND RARITAN TOWNSHIP FRIDAY MORXIXG, MAY 12, 1939. PRICE THREE CENTS TUESDAY'S ELECTION FORDS GIVES O.K. Champions of the People! REED PLEADS NO MAYOR. HEALTH The People TO FIRE BUDGET DEFENSE TO ALLINSPECTOR URGE Have Spoken! . IN 4TH ELECTION COUNTS MONDAY 'CLEAJHIPWEEK' It is a pleasure to be able to congratulate Walter C. j Christensen, Victor Pedersen, Henry H. Troger, Jr., James BOTH ITEMS RECEIVE GOOD CHANGES FORMER PLEA AT ADDITIONAL EQUIPMENT TO MAJORITIES: OVER 300 REQUEST OF COUNSEL C. Forgione and John E. Pardun on their victory in Raritan HAUL AWAY REFUSE VOTES CAST D. THOMPSON EVERY DAY Township Tuesday . They put up an outstanding fight . And, the municipality's 5,000 voters who visited the FORJ3S.—Druggists reported a RARITAN TOWNSHIP. — Wil- FORDS.—Clean Up and Home decided drop in headache powder liam H. Reed, Si1., former secretary Improvement Week which will be; ballot boxes had enough faith in the Administration can- sales. Doctors dismissed all their of the Oak Tree Board of Fire gin Monday and continue through didates to elect them by comfortable majorities. nervous patients and once again Commissioners in Raritan Town- Saturday will give local residents Fords is in a state of peace and ship, pleaded non vult or no de- an opportunity tp dispose of re- The results of Tuesday's election prove the worth of quiet, for the voters have finally fense in Quarter Sessions Court fuse which may have gathered in Messrs. -

The Inventory of the Leslie Charteris Collection

The Inventory of the Leslie Charteris Collection #39 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center charteris.inv CHARTERIS, LESLIE (1907-1993) Addenda, July 1972 - 1993 [13 Paige boxes, Location: SB2G] I. MANUSCRIPTS Box 1 Scripts bound. "The Saint Show." Volumes 1-12. Radio scripts, 1945-1948. "The Fairy Tale Murder." n.d. "Lady on a Train." Film script, 1943. "Two Smart People" by LC and Ethel Hill, 1944. Box 2 "Return of the Saint" TV Series. 1970s. "Appointment in Florence" "Armageddon Alternative" "The Arrangement" "Assault Force" "The Debt Collectors" "The Diplomats Daughter" "Double Take" "Dragonseed" "Duel in Venice" "The Imprudent Professor" "The Judas Game" "Lady on a Train" 1 "The Murder Cartel" "The Nightmare Man" "The Obono Affair" "One Black September" "The Organisation Man" "The Poppy Chain" Box 2 "Prince of Darkness" "The Roman Touch" "Tower Bridge is Falling Down" "Vanishing Point" Part 1 The Salamander Part 2 The Sixth Man "Vicious Circle" "The Village that Sold Its Soul" "Yesterday's Hero" "The Saint" series, 1989. "The Big Bang" "The Blue Dulac" "The Brazilian Connection" "The Software Murders" Synopses for "Saint" scripts with reply 1972, 3 1973, 2 1974, 6 1975, 5 1976, 3 1977, 3 1978, 1 1979, 8 1980, 6 1981, 7 2 1982, 7 1983, 6 1984, 4 1985, 3 1986, 1 1987, 1 1988, 1 Synopses without reply 1962, 1 1971, 1 1973, 3 1974, 1 1977, 1 1978, 2 1981, 1 1983, 5 1984, 6 1987, 1 Eight undated Synopses Box 3 Radio scripts (unbound):#16, 28, 33, 37, 38, 41, 43, 45, 46, and two without numbers. -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping as usual that you are all safe and well in these troubled times. Our cinema doors are still well and truly open, I’m pleased to say, the channel has been transmitting 24 hours a day 7 days a week on air with a number of premières for you all and orders have been posted out to you all every day as normal. It’s looking like a difficult few months ahead with lack of advertising on the channel, as you all know it’s the adverts that help us pay for the channel to be transmitted to you all for free and without them it’s very difficult. But we are confident we can get over the next few months. All we ask is that you keep on spreading the word about the channel in any way you can. Our audiences are strong with 4 million viewers per week , but it’s spreading the word that’s going to help us get over this. Can you believe it Talking Pictures TV is FIVE Years Old later this month?! There’s some very interesting selections in this months newsletter. Firstly, a terrific deal on The Humphrey Jennings Collections – one of Britain’s greatest filmmakers. I know lots of you have enjoyed the shorts from the Imperial War Museum archive that we have brought to Talking Pictures and a selection of these can be found on these DVD collections. -

Local Blogger Settles Lawsuit Against Fairhope Council

HEALTH: Paint the town pink, PAGE 23 World War I and II exhibit PAGE 5 High School football The Courier PAGE 14 INSIDE OCTOBER 24, 2018 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ Candidate Meet and Greet Thursday Local blogger settles lawsuit Fairhope in Daphne city The Eastern Shore Cham- against Fairhope council ber of Commerce will host its Candidate Meet and treasurer Greet on Thursday, Oct. 25 By CLIFF MCCOLLUM speak during the public com- for many reasons,” Ripp from 5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. [email protected] ments portion of the Aug. 28, wrote. “One being, I knew the fired at Bayside Academy’s Pilot 2017, city council meeting - a Council and Burrell would Center Theatre at 303 Dryer Local blogger Paul Ripp’s move which Ripp claimed vio- never apologize and that going By CLIFF MCCOLLUM Avenue in Daphne. Meet the lawsuit against Fairhope lated his constitutional rights. to court was going to be very City Council President Jack Ripp filed suit against Burrell expensive for the city.” [email protected] local candidates who will Burrell and the rest of the city and the city in Dec. 2017. Ripp went on to say he be on the general election council has been settled, ac- In a Friday, Oct. 19 post on heard Burrell had been “brag- Fairhope City Trea- ballot on Nov. 6 and learn cording to a recent blog post his blog entitled “Loser,” Ripp ging” about the outcome of surer Mike Hinson was more about their campaign by Ripp and documents filed said he settled the suit with the case.