When the Saints Go Marching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

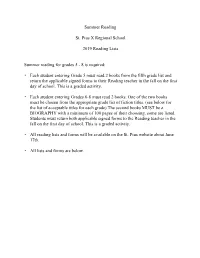

Summer Reading St. Pius X Regional School 2019 Reading Lists Summer Reading for Grades 5

Summer Reading St. Pius X Regional School 2019 Reading Lists Summer reading for grades 5 - 8 is required: ▪ Each student entering Grade 5 must read 2 books from the fifth grade list and return the applicable signed forms to their Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. This is a graded activity. ▪ Each student entering Grades 6-8 must read 2 books. One of the two books must be chosen from the appropriate grade list of fiction titles. (see below for the list of acceptable titles for each grade) The second books MUST be a BIOGRAPHY with a minimum of 100 pages of their choosing, some are listed. Students must return both applicable signed forms to the Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. This is a graded activity. ▪ All reading lists and forms will be available on the St. Pius website about June 17th. ▪ All lists and forms are below. ST. PIUS X - SUMMER READING Incoming Grade 8 (2019) 1. Each student entering Grade 8 must read 2 books. One of the two books must be chosen from the appropriate grade list of fiction titles. (see below for the list of acceptable titles for 8th grade) 2. The second books MUST be a BIOGRAPHY with a minimum of 100 pages of their choosing, some are listed. 3. Students must return the applicable signed forms (one form for the fiction title and one form for the biography title) to the Reading teacher in the fall on the first day of school. (both forms are below) 4. -

The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Online

Ch0XW [Mobile pdf] The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Online [Ch0XW.ebook] The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) Pdf Free Leslie Charteris ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2154235 in Books 2014-06-24 2014-06-24Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x 1.00 x 5.50l, .0 #File Name: 1477843078256 pages | File size: 54.Mb Leslie Charteris : The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Saint and the Templar Treasure (The Saint Series): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. What a Fabulous Adventure!By Carol KiekowThis book is another entertaining adventure of The Saint. I was on the edge of my seat throughout. I heartily recommend it!0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Good "Saint" storyBy Carolyn GravesGood "Saint" story. Location as much a character as the people. Kept my interest and kept me guessing throughout.4 of 13 people found the following review helpful. Super ReaderBy averageSimon Templar is in France, and has an incident on the road with a young woman. He ends up at a small local vineyard that is in financial trouble. The girl, Mimette requests his help. There is a family struggle over the place, and an uncle trying to find an old obscure Templar treasure on the property.Violence ensues, and the treasure is not what anyone thinks. Simon Templar is taking a leisurely drive though the French countryside when he picks up a couple of hitchhikers who are going to work at Chateau Ingare, a small vineyard on the site of a former stronghold of the Knights Templar. -

Read Book the Saint Returns

THE SAINT RETURNS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Leslie Charteris | 212 pages | 24 Jun 2014 | Amazon Publishing | 9781477842980 | English | Seattle, United States The Saint Returns PDF Book Create outlines for what you want to be accomplished. This was scrapped, and Ian Ogilvy took over the halo for 24 episodes as Simon Templar. This amount is subject to change until you make payment. He also somewhat deplored the tendency for the Saint to be seen primarily as a detective, and this was even stated in some of the later stories, e. Reading about Charteris' "amiable rascal" is infinitely easier and much more relaxing than writing more stories about my own fictitious rascal, Misfit Lil whom I like to think shares a trait or two with Mr Simon Templar! Honestly it was probably the highlight of an episode that mostly spun its wheels. Alyssa Milano legs boots feet Chad Allen magazine pin up clipping. Balthazar Getty Alyssa Milano magazine clipping pin up s vintage. He steals from rich criminals and keeps the loot for himself usually in such a way as to put the rich criminals behind bars. He threatens the biggest explosion of all unless sculptress Lynn Jackson is Hell In order for Eugene and Hitler to get out of hell, Eugene has to overcome the thing that has been keeping him in Hell. Simon Templar 24 episodes, The Saint also ventured into the comics section of our newspapers, battling alongside Dick Tracy and the other Sunday heroes. Seller's other items. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. -

Session 20 Speak

SESSION 20 SPEAK GOAL The goal of this is session is for the teens to see the communion of saints as their extended family, to understand what it means to be a witness of the faith, and to get to know a few modern saints. KEY CONCEPTS Confirmation calls us to be witnesses of faith and provides us with the graces to do so. Being a witness means being a martyr; martyrdom does not necessarily mean dying for the faith, but requires a willingness to sacrifice and suffer for truth. When learning how to become better witnesses, we should look to the examples of other members of the Church — particularly Mary and the saints. KEY TERMS Martyr: A witness to the truth of the faith, in which the martyr endures even death to be faithful to Christ. Saint: The “holy one” who leads a life in union with God through the grace of Christ and receives the reward of eternal life. SCRIPTURE: 2 Timothy 1:6-8, Acts 2:1-11, Matthew 16:24-27 CATECHISM: 954-959, 963-969, 1302-1304, 2471-2474 ABOUT THIS CONFIRMATION SESSION The Gather is a fun game of Family Feud, which helps emphasize that this is a session about family, namely the communion of saints. The Proclaim teaches about the important role Mary and the communion of saints play in the teens’ lives. The Break gives the teens an opportunity to get to know a saint from our modern era more personally. The Send is a group prayer during which the teens ask the saints to pray for them through one of the Church’s oldest prayers, the Litany of Saints. -

The Inventory of the Leslie Charteris Collection

The Inventory of the Leslie Charteris Collection #39 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center charteris.inv CHARTERIS, LESLIE (1907-1993) Addenda, July 1972 - 1993 [13 Paige boxes, Location: SB2G] I. MANUSCRIPTS Box 1 Scripts bound. "The Saint Show." Volumes 1-12. Radio scripts, 1945-1948. "The Fairy Tale Murder." n.d. "Lady on a Train." Film script, 1943. "Two Smart People" by LC and Ethel Hill, 1944. Box 2 "Return of the Saint" TV Series. 1970s. "Appointment in Florence" "Armageddon Alternative" "The Arrangement" "Assault Force" "The Debt Collectors" "The Diplomats Daughter" "Double Take" "Dragonseed" "Duel in Venice" "The Imprudent Professor" "The Judas Game" "Lady on a Train" 1 "The Murder Cartel" "The Nightmare Man" "The Obono Affair" "One Black September" "The Organisation Man" "The Poppy Chain" Box 2 "Prince of Darkness" "The Roman Touch" "Tower Bridge is Falling Down" "Vanishing Point" Part 1 The Salamander Part 2 The Sixth Man "Vicious Circle" "The Village that Sold Its Soul" "Yesterday's Hero" "The Saint" series, 1989. "The Big Bang" "The Blue Dulac" "The Brazilian Connection" "The Software Murders" Synopses for "Saint" scripts with reply 1972, 3 1973, 2 1974, 6 1975, 5 1976, 3 1977, 3 1978, 1 1979, 8 1980, 6 1981, 7 2 1982, 7 1983, 6 1984, 4 1985, 3 1986, 1 1987, 1 1988, 1 Synopses without reply 1962, 1 1971, 1 1973, 3 1974, 1 1977, 1 1978, 2 1981, 1 1983, 5 1984, 6 1987, 1 Eight undated Synopses Box 3 Radio scripts (unbound):#16, 28, 33, 37, 38, 41, 43, 45, 46, and two without numbers. -

Find PDF > Saint Overboard

NCLWTTVKIHXZ > PDF Saint Overboard Saint Overboard Filesize: 1.53 MB Reviews Thorough guide for pdf enthusiasts. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. Its been printed in an remarkably simple way which is only soon after i finished reading through this pdf by which really altered me, change the way i believe. (Dr. Rowena Wiegand) DISCLAIMER | DMCA CBJHFWSI5IWI < PDF ^ Saint Overboard SAINT OVERBOARD Hodder & Stoughton General Division. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, Saint Overboard, Leslie Charteris, How could the Saint possibly resist the chance of a treasure hunt? When his sailing trip along the French coast is interrupted by gunfire and shouting, naturally he gets curious. The cause of the commotion is a group of men pursuing a young woman - and once Simon steps in to help the damsel in distress, he soon finds himself on the trail of a group of modern-day pirates - and searching for a huge amount of gold. Read Saint Overboard Online Download PDF Saint Overboard OBLOPD8C0SZV // eBook Saint Overboard You May Also Like TJ new concept of the Preschool Quality Education Engineering the daily learning book of: new happy learning young children (3-5 years) Intermediate (3)(Chinese Edition) paperback. Book Condition: New. Ship out in 2 business day, And Fast shipping, Free Tracking number will be provided aer the shipment.Paperback. Pub Date :2005-09-01 Publisher: Chinese children before making Reading: All books are the... Download ePub » TJ new concept of the Preschool Quality Education Engineering the daily learning book of: new happy learning young children (2-4 years old) in small classes (3)(Chinese Edition) paperback. -

Migrating Birds at a Stopover Site in the Saint Croix River Valley

Wilson Bull., 105(2), 1993, pp. 265-284 MIGRATING BIRDS AT A STOPOVER SITE IN THE SAINT CROIX RIVER VALLEY A. R. WEISBROD,,~‘ C. J. BURNETT, ’ J. G. TURNRR,,~‘ AND DWATN W. WARNERS ABSTRACT.-We captured 16,527 birds in five habitats at Sandrock Cliff, Saint Croix National Riverway, during spring and fall of 1985, 1986, and 1987. Nearctic-Neotropic migrants comprised 66% of the 118 species captured. They comprised the majority of individuals taken in spring (82.5%), autumn (68.9%), and overall (72.7%). Nearctic-Neo- tropic migrants averaged 15 weeks between median capture dates, arriving later in spring and departing earlier in fall than temperate zone migrants. The latter spend about 20 weeks elsewhere between median capture dates. Differences in spring and fall capture rates in five habitats suggestsbirds shift habitat use seasonally. ReceivedI I May 1992, accepted25 Nov. 1992. The biological community and habitat requirements of long distance avian migrants along their regular annual migration routes are known poorly, and the relative importance of particular habitats to the migrating populations remains to be determined. Most observers are aware that survival of migrating populations is dependent both upon successful re- production during the northern summer season and a successful non- breeding wintering period in the tropics. It also appears the non-breeding portions of the long distance migrants ’ life cycles are as critical to survival of the population as the reproductive periods (Recher 1966, Rappole et al. 1983, Berthold and Terrill 199 1). Because similar economic and tech- nological pressures exist for both regions, one may assume reasonably that North American habitats used during annual migrations may suffer reduction and fragmentation similar to that occurring in tropical America (see Robbins 1979, Robbins et al. -

Filmed Across the World, Made at Elstree’: How Television Made at Elstree in the 1960S and 70S Brought a Global Experience to the Small Screen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Hertfordshire Research Archive ‘Filmed Across the World, Made at Elstree’: How television made at Elstree in the 1960s and 70s brought a global experience to the small screen The various studios of Elstree and Borehamwood were, in the 1960s and 70s, home to globetrotting adventurers including The Saint, Department S, Jason King, Danger Man, and The Baron. While many of the shows made featured the globetrotting exploits of their leading characters – Simon Templar, international playboy; Jason King, Interpol agent and novelist; and John Drake, spy and fixer for international organisations – the production crew rarely, if ever, left the confines of the TV sound stages and backlot, except for a brief dash down Borehamwood high street or into rural Hertfordshire. This paper will discuss the operations and technical methodologies used on a weekly basis by production crews in their attempts to recreate Rome, Paris, Madrid and even the Sahara Desert on small budgets, using stock footage and with limited materials. During the 1960s, the studios of Elstree and Borehamwood produced some of the most adventurous and prolific television productions in the UK. Three major studio sites (all of them actually in Borehamwood, not in Elstree) – MGM British Studios, Associated British Productions (ABPC) and ATV Studios – were all producing television content 52 weeks of the year. “Elstree’s” output during this time was at its peak. Production crews at Elstree were able to make shows with an international flavour, while barely leaving the studio. -

The Saint Club Merchandise September 2002

The Saint Club Merchandise September 2002 The Saint Club, London www.saint.org The Saint: The Official 2003 Calendar Published by Slow Dazzle Worldwide Ltd. and with exclusive input from Ian Dickerson as well as access to the Carlton archives, this is a unique publication that every fan of the work of Simon Templar and the adventures of Leslie Charteris will want on their wall. Available from The Saint Club cheaper then you’ll find it in the High Street (least if you’re in the UK)! UK: £8.99 Europe: £10.49 North America: $15.99 Rest of World: £11.49 DVD: The Saint and the Fiction Makers (region 2) With Carlton progressively less interested in issuing region 2 Saint DVDs French company PVB Editions has taken up the challenge and issued a collectors edition of The Saint and the Fiction Makers on DVD. This is a two disc set featuring a version of the movie dubbed into French and a version of the movie in English with French subtitles. Plus lots of extras from ITC expert Jaz Wiseman, Saint webmaster Dan Bodenheimer…and some guy called Dickerson. Available for sale in France, Belgium and Switzerland, The Saint Club is the only place in the UK to offer The Fiction Makers on DVD. UK: £14.99 Europe: £15.99 North America: $28.99 Rest of World: £16.99 A Slight Hangover is former TV Saint Ian Ogilvy's third book and was published by Writers Club Press in 2000. "A Slight Hangover is a funny and affectionate look at three generations of clever, witty and thoroughly immoral people. -

1 Exploring Detective Films in the 1930S and 1940S: Genre, Society and Hollywood

Notes 1 Exploring Detective Films in the 1930s and 1940s: Genre, Society and Hollywood 1. For a discussion of Hollywood’s predilection for action in narratives, see Elsaesser (1981) and the analysis of this essay in Maltby (1995: 352−4). 2. An important strand of recent criticism of literary detective fiction has emphasised the widening of the genre to incorporate female and non-white protagonists (Munt, 1994; Pepper, 2000; Bertens and D’Haen, 2001; Knight, 2004: 162−94) but, despite Hollywood’s use of Asian detectives in the 1930s and 1940s, these accounts are more relevant to contemporary Hollywood crime films. 3. This was not only the case in B- Movies, however, as Warner’s films, includ- ing headliners, in the early 1930s generally came in at only about an hour and one- quarter due to budgetary restraints and pace was a similar neces- sity. See Miller (1973: 4−5). 4. See Palmer (1991: 124) for an alternative view which argues that ‘the crimi- nal mystery dominates each text to the extent that all the events in the narrative contribute to the enigma and its solution by the hero’. 5. Field (2009: 27−8), for example, takes the second position in order to create a binary opposition between the cerebral British whodunnit and the visceral American suspense thriller. 6. The Republic serials were: Dick Tracyy (1937), Dick Tracy Returns (1938), Dick Tracy’s G- Men (1939) and Dick Tracy vs Crime, Inc. (1941) (Langman and Finn, 1995b: 80). 7. The use of the series’ detectives in spy-hunter films after 1941, however, modifies this relationship by giving them at least an ideological affiliation with the discourses of freedom and democracy that Hollywood deploys in its propagandistic representation of the Allies in general and the United States in particular. -

The Saint, the Free

FREE THE SAINT, THE PDF Madeline Hunter | 405 pages | 04 Nov 2003 | Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc | 9780553585902 | English | New York, United States St. George - Home The The Saint film series refers to eight The Saint movies made by RKO Pictures between andbased on some of the books in British author Leslie Charteris ' long-running series about the The Saint character Simon Templarbetter known as The Saint. The Saint few years after creating the character inCharteris was successful the getting RKO Radio Pictures interested in a film based on one of his books. The first, The Saint in New Yorkcame in and was based on The Saint novel of the same name. The film was a success and seven more films the rapidly. They were sometimes based upon The Saint by Charteris, while others were based loosely on his novels or novellas. George Sanders took over from Hayward as The Saint in the second film, and starred in a further four between andbefore being enticed by RKO to play the lead in their forthcoming series about The Thewhich they made into a blatant copy of The Saint. Charteris argued that it was a case of copyright infringement, as RKO's version of The Falcon was an obvious the of his own character, and the fact that their film starred George Sanders, who personified The Saint after having played him in five The Saint the seven films released up to that point, made this even more obvious. The legal dispute forced RKO to put the film on hold. The film was released in both countries in In the s, RKO also purchased the the to The Saint a film adaptation of Saint Overboardbut no such film was ever produced. -

The Saint Mystery Library Are Almost All Anthologies

The Saint Books An overview The two book series indexed here are only indirectly related to each other. In each case the books were issued by the company that was then publishing The Saint Mystery Magazine. However, the magazine had changed hands between the two series, including a year’s hiatus between the two publishers. The two constants over the magazine’s history were the editorial direction of Leslie Charteris and the direct editorship of Hans Stefan Santesson. The publisher of Great American Publications was given as Henry Scharf in issues of The Saint Mystery Magazine. The ownership of Fiction Publishing Company remains a mystery. One would expect it to be revealed by the annual Post Office-mandated Statements of Ownership in the magazine, but this incarnation did not have a second- class mailing permit so they never printed one. The indexing of each series presents its own problems. The Saint Mystery Library are almost all anthologies. The volumes list Leslie Charteris as the editor of the series, which I have stretched to give him credit as editor of the individual volumes. The Saint Novels were all reprints of previously published Saint books, all by Leslie Charteris. Obviously an author Index of the book titles for either series would have only one author: Leslie Charteris. Thus I have dispensed with that level of Author Index and produced a combined Author Index, containing both the book titles and the contents. The book titles are printed in italics. The usual citations for prior publications of the books didn’t fit into this format, so I annotated them into the Numerical Listings instead.