Philosophy of Biology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

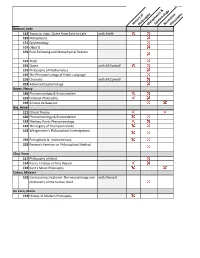

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

Development, Evolution, and Adaptation Author(S): Kim Sterelny Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol

Philosophy of Science Association Development, Evolution, and Adaptation Author(s): Kim Sterelny Source: Philosophy of Science, Vol. 67, Supplement. Proceedings of the 1998 Biennial Meetings of the Philosophy of Science Association. Part II: Symposia Papers (Sep., 2000), pp. S369-S387 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Philosophy of Science Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/188681 Accessed: 03/03/2010 17:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Philosophy of Science Association and The University of Chicago Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Philosophy of Science. -

Foucault's Darwinian Genealogy

genealogy Article Foucault’s Darwinian Genealogy Marco Solinas Political Philosophy, University of Florence and Deutsches Institut Florenz, Via dei Pecori 1, 50123 Florence, Italy; [email protected] Academic Editor: Philip Kretsedemas Received: 10 March 2017; Accepted: 16 May 2017; Published: 23 May 2017 Abstract: This paper outlines Darwin’s theory of descent with modification in order to show that it is genealogical in a narrow sense, and that from this point of view, it can be understood as one of the basic models and sources—also indirectly via Nietzsche—of Foucault’s conception of genealogy. Therefore, this essay aims to overcome the impression of a strong opposition to Darwin that arises from Foucault’s critique of the “evolutionistic” research of “origin”—understood as Ursprung and not as Entstehung. By highlighting Darwin’s interpretation of the principles of extinction, divergence of character, and of the many complex contingencies and slight modifications in the becoming of species, this essay shows how his genealogical framework demonstrates an affinity, even if only partially, with Foucault’s genealogy. Keywords: Darwin; Foucault; genealogy; natural genealogies; teleology; evolution; extinction; origin; Entstehung; rudimentary organs “Our classifications will come to be, as far as they can be so made, genealogies; and will then truly give what may be called the plan of creation. The rules for classifying will no doubt become simpler when we have a definite object in view. We possess no pedigrees or armorial bearings; and we have to discover and trace the many diverging lines of descent in our natural genealogies, by characters of any kind which have long been inherited. -

A Different Kind of Animal: How Culture

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. INTRODUCTION Stephen Macedo What makes humans special? Is it, as many have argued, our superior intelligence that sets us apart from other species? In the lectures and discussions that follow, Robert Boyd, a distinguished professor of human evolution and social change, refines the question and rejects the common answer. Putting aside the more familiar question of human unique- ness, Boyd asks why humans so exceed other species when it comes to broad indices of ecological success such as our ability to adapt to and thrive in such a wide variety of hab- itats across the globe. Ten thousand years ago, humans al- ready occupied the entire globe except Antarctica and a few remote islands. No other species comes close. What explains our outlier status if not our “big brains”? Humans adapt to a vast variety of changing environments not mainly by applying individual intelligence to solve prob- lems, but rather via “cumulative cultural adaptation” and, over the longer term, Darwinian selection among cultures with different social norms and moral values. Not only are humans part of the natural world, argues Boyd, but human culture is part of the natural world. Culture makes us “a different kind of animal,” and “culture is as much a part of human biology as our peculiar pelvis or the thick enamel that covers our molars.” With his many coauthors, especially Peter Richerson, Robert Boyd has for three decades pioneered an important approach to the study of human evolution that focuses on the population dynamics of culturally transmitted informa- tion. -

Philosophical Perspectives on Evolutionary Theory

Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia, 92: 461–464, 2009 Philosophical perspectives on Evolutionary Theory A Tapper Centre for Applied Ethics & Philosophy, Curtin University of Technology, Bentley, WA [email protected] Manuscript received December 2009; accepted February 2010 Abstract Discussion of Darwinian evolutionary theory by philosophers has gone through a number of historical phases, from indifference (in the first hundred years), to criticism (in the 1960s and 70s), to enthusiasm and expansionism (since about 1980). This paper documents these phases and speculates about what, philosophically speaking, underlies them. It concludes with some comments on the present state of the evolutionary debate, where rapid and important changes within evolutionary theory may be passing by unnoticed by philosophers. Keywords: Darwinism, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology; evolution. Introduction author. Biologists such as Richard Dawkins, Stephen Jay Gould, Steve Jones and Simon Conway Morris are Darwin once said that he had no aptitude for prominent. So also are historians of science, such as Peter philosophy: “My power to follow a long and purely Bowler, Janet Browne, Adrian Desmond and James R. abstract train of thought is very limited; I should, Moore. Equally likely, however, one might be introduced moreover, never have succeeded with metaphysics or to evolutionary theory by a philosopher of biology, for mathematics” (Darwin 1958). This was not false modesty; example Michael Ruse, David Hull or Kim Sterelny. (For -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Evolutionary Epistemology in James' Pragmatism J

35 THE ORIGIN OF AN INQUIRY: EVOLUTIONARY EPISTEMOLOGY IN JAMES' PRAGMATISM J. Ellis Perry IV University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth "Much struck." That was Darwin's way of saying that something he observed fascinated him, arrested his attention, surprised or puzzled him. The words "much struck" riddle the pages of bothhis Voyage ofthe Beagle and his The Origin of Species, and their appearance should alert the reader that Darwin was saying something important. Most of the time, the reader caninfer that something Darwin had observed was at variance with what he had expected, and that his fai th in some alleged law or general principle hadbeen shaken, and this happened repeat edly throughout his five year sojourn on the H.M.S. Beagle. The "irritation" of his doubting the theretofore necessary truths of natu ral history was Darwin's stimulus to inquiry, to creative and thor oughly original abductions. "The influence of Darwinupon philosophy resides inhis ha ving conquered the phenomena of life for the principle of transi tion, and thereby freed the new logic for application to mind and morals and life" (Dewey p. 1). While it would be an odd fellow who would disagree with the claim of Dewey and others that the American pragmatist philosophers were to no small extent influenced by the Darwinian corpus,! few have been willing to make the case for Darwin's influence on the pragmatic philosophy of William James. Philip Wiener, in his well known work, reports that Thanks to Professor Perry's remarks in his definitive work on James, "the influence of Darwin was both early and profound, and its effects crop up in unex pected quarters." Perry is a senior at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmoltth. -

Cultural Group Selection Plays an Essential Role in Explaining Human Cooperation: a Sketch of the Evidence

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2016), Page 1 of 68 doi:10.1017/S0140525X1400106X, e30 Cultural group selection plays an essential role in explaining human cooperation: A sketch of the evidence Peter Richerson Emily K. Newton Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California– Department of Psychology, Dominican University of California, San Rafael, CA Davis, Davis, CA 95616 94901 [email protected] [email protected] http://emilyknewton.weebly.com/ www.des.ucdavis.edu/faculty/richerson/richerson.htm Nicole Naar Ryan Baldini Department of Anthropology, University of California–Davis, Graduate Group in Ecology, University of California–Davis, Davis, CA 95616 Davis, CA 95616 [email protected] https://sites.google.com/site/ryanbaldini/ [email protected] Adrian V. Bell Lesley Newson Department of Anthropology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112 Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California– [email protected] http://adrianbell.wordpress.com/ Davis, Davis, CA 95616 [email protected] [email protected] Kathryn Demps https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lesley_Newson/ Department of Anthropology, Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725 [email protected] Cody Ross http://sspa.boisestate.edu/anthropology/faculty-and-staff/kathryn- Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM 87501 demps/ [email protected] http://scholar.google.com/citations?user=xSugEskAAAAJ Karl Frost Graduate Group in Ecology, University of California–Davis, Davis, CA 95616 Paul E. Smaldino [email protected] https://sites.google.com/site/karljosephfrost/ Department of Anthropology, University of California–Davis, Davis, CA 95616 [email protected] http://www.smaldino.com/ Vicken Hillis Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California– Timothy M. -

472 Philip Kitcher Preludes to Pragmatism

Philosophy in Review XXXIII (2013), no. 6 Philip Kitcher Preludes to Pragmatism: Toward a Reconstruction of Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2012. 464 pages $45.00 (cloth ISBN 978–0–19–989955–5) This book collects seventeen of Philip Kitcher’s essays from the past two decades. All but two have been published elsewhere, and several are quite well-known. ‘The Naturalists Return’, for example, appeared in Philosophical Review’s 1992 centennial issue, and is a staple of reading lists in epistemology and the philosophy of science. But the book frames these essays in a valuable new way. In the period from which these essays are drawn, Kitcher moved steadily toward an embrace of pragmatism, and the book presents them as milestones in this development: tentative applications of pragmatist ideas to a range of topics. Hence the word ‘prelude’. Kitcher says that he is not yet ready to present a ‘fully developed pragmatic naturalist position’ and that he is merely giving ‘pointers’ toward such a position (xvi-xvii). But this modesty does not do justice to the sophistication of his pragmatism. Preludes to Pragmatism is a rich and rewarding book that will interest philosophers of many different stripes. It may also prove to be an important contribution to the history of pragmatism. The book’s lengthy introduction puts the essays in context. Kitcher seems surprised to have wound up a pragmatist. ‘Two decades ago’, he writes, ‘I would have seen the three canonical pragmatists—Peirce, James, and Dewey—as well-intentioned but benighted, laboring with crude tools to develop ideas that were far more rigorously and exactly shaped by… what is (unfortunately) known as “analytic” philosophy’ (xi). -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal Science and Scientism in Popular Science Writing de Ridder, G.J. published in Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective 2014 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) de Ridder, G. J. (2014). Science and Scientism in Popular Science Writing. Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective, 3(12), 23-39. http://wp.me/p1Bfg0-1KE General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective, 2014 Vol. 3, No. 12, 23-39. http://wp.me/p1Bfg0-1KE Science and Scientism in Popular Science Writing Jeroen de Ridder, VU University Amsterdam Abstract If one is to believe recent popular scientific accounts of developments in physics, biology, neuroscience, and cognitive science, most of the perennial philosophical questions have been wrested from the hands of philosophers by now, only to be resolved (or sometimes dissolved) by contemporary science. -

Arxiv:0809.1275V2

How eccentric orbital solutions can hide planetary systems in 2:1 resonant orbits Guillem Anglada-Escud´e1, Mercedes L´opez-Morales1,2, John E. Chambers1 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT The Doppler technique measures the reflex radial motion of a star induced by the presence of companions and is the most successful method to detect ex- oplanets. If several planets are present, their signals will appear combined in the radial motion of the star, leading to potential misinterpretations of the data. Specifically, two planets in 2:1 resonant orbits can mimic the signal of a sin- gle planet in an eccentric orbit. We quantify the implications of this statistical degeneracy for a representative sample of the reported single exoplanets with available datasets, finding that 1) around 35% percent of the published eccentric one-planet solutions are statistically indistinguishible from planetary systems in 2:1 orbital resonance, 2) another 40% cannot be statistically distinguished from a circular orbital solution and 3) planets with masses comparable to Earth could be hidden in known orbital solutions of eccentric super-Earths and Neptune mass planets. Subject headings: Exoplanets – Orbital dynamics – Planet detection – Doppler method arXiv:0809.1275v2 [astro-ph] 25 Nov 2009 Introduction Most of the +300 exoplanets found to date have been discovered using the Doppler tech- nique, which measures the reflex motion of the host star induced by the planets (Mayor & Queloz 1995; Marcy & Butler 1996). The diverse characteristics of these exoplanets are somewhat surprising. Many of them are similar in mass to Jupiter, but orbit much closer to their 1Carnegie Institution of Washington, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, 5241 Broad Branch Rd.