Chapter 10 New Issues, New Stalemate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Column and CC News

1.e4 d5 2.e5 e6 3.d4 Nc6 4.Nf3 Bb4+ 5.c3 Be7 6.g3 Bd7 7.Bd3 ½–½ Counted among the mysteries that I just do not understand... PHILIDOR’S DEFENSE (C41) White: Matthew Ross (800) Black: Paul Rellias The Check Is in the Mail IECG 2005 DECEMBER 2006 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 f6 4. Bc4 Ne7 5. This month I honor a 25-year old dxe5 fxe5 6. 00 Bg4 7. Nxe5 Rg8 8. tradition of featuring miniature games in Bxg8 h6 9. Bf7 mate “The Check”. You may find it surprising that miniature games can Sometimes postal chess is an easy game happen to all ranks of chess players. – you just follow book for 10 to 15 They do, and here is the proof. The moves or so, and when your opponent February issue of Chess Life will also thinks for himself, you’ve got ‘em! contain some of these snowflakes, little wonders of nature. SICILIAN DEFENSE (B99) White: Olita Rause (2720) There are more tactics in this mini than Black: Vladimir Hefka (2574) you will find in three regular-sized 18th World Championship, 2003 games. 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 RUY LOPEZ (C70) 5.Nc3 a6 6.Bg5 e6 7.f4 Be7 8.Qf3 Qc7 White: Nowden 9.0–0–0 Nbd7 10.g4 b5 11.Bxf6 Nxf6 Black: Kristensen 12.g5 Nd7 13.f5 Nc5 14.f6 gxf6 15.gxf6 Correspondence 1933 Bf8 16.Rg1 h5 17.a3 Bd7 18.Kb1 Bc6 19.Bh3 Qb7 20.b4 1-0 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Bc5 5.c3 b5 6.Bc2 d5 7.d4 exd4 8.cxd4 Bb6 9.0–0 Bg4 10.exd5 Qxd5 11.Be4 Qd7 12.Qe1 0–0–0 13.Bxc6 Qxc6 14.Ne5 XABCDEFGHY Qe6 15.Qe4 c6 16.Qxg4 f5 17.Qxg7 8 +-+- ( Bxd4 18.Bf4 Bxb2 19.Nc3 Bxa1 20.Qa7 1–0 7++-++-' 6+-+& Two amateurs distill the essence of the 5+-+-+% Grandmaster draw. -

1999/6 Layout

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

The Modern Defence: Move by Move PDF Book

THE MODERN DEFENCE: MOVE BY MOVE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cyrus Lakdawala | 400 pages | 20 Nov 2012 | EVERYMAN CHESS | 9781857449860 | English | London, United Kingdom The Modern Defence: Move by Move PDF Book Please try to maintain a semblance of civility at all times. When to resign - Etiquette - An honest appeal Optimissed 7 min ago. Published November 20th by Everyman Chess first published October 7th Cochrane vs Somacarana 34 Calcutta B06 Robatsch 8. Rxh7 9. Error rating book. Nc3 in the actual game. Aug 10, Chapter 1 — Introduction — initial remarks and comments. Cyrus Lakdawala. I know he is notoriously hit-and-miss as an author. Kxf7, 6. The flexibility and toughness of the Modern Defense has provoked some very aggressive responses by White, including the crudely named Monkey's Bum , a typical sequence being 1. Welcome back. Chapter 8 — The Fianchetto Variation: g3-Bg2 setups — the quiet, but no less venomous setups involving an early fianchetto of the light-squared bishop. Question feed. Bg7 3. See something that violates our rules? Please observe our posting guidelines: No obscene, racist, sexist, or profane language. Be2, Black can retreat the knight or gambit a pawn with Therefore, I find it an advantage to block these pieces by pawns. Nf3, Black can play Jul 22, 2. Numerous hours were spent analyzing, importing, commenting, fixing mistakes, fixing the fixes of mistakes, replying to beta tester comments, improving the initial version, etc. B06 Robatsch. Transpositions are possible after 2. A repertoire for my favourite opening for the Black pieces — the Modern Defence — was among them. To ask other readers questions about The Modern Defence , please sign up. -

Inside Russia's Intelligence Agencies

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES Mark Galeotti For his birthday in 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin was treated to an exhibition of faux Greek friezes showing SUMMARY him in the guise of Hercules. In one, he was slaying the • Russia’s intelligence agencies are engaged in an “hydra of sanctions”.1 active and aggressive campaign in support of the Kremlin’s wider geopolitical agenda. The image of the hydra – a voracious and vicious multi- headed beast, guided by a single mind, and which grows • As well as espionage, Moscow’s “special services” new heads as soon as one is lopped off – crops up frequently conduct active measures aimed at subverting in discussions of Russia’s intelligence and security services. and destabilising European governments, Murdered dissident Alexander Litvinenko and his co-author operations in support of Russian economic Yuri Felshtinsky wrote of the way “the old KGB, like some interests, and attacks on political enemies. multi-headed hydra, split into four new structures” after 1991.2 More recently, a British counterintelligence officer • Moscow has developed an array of overlapping described Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) as and competitive security and spy services. The a hydra because of the way that, for every plot foiled or aim is to encourage risk-taking and multiple operative expelled, more quickly appear. sources, but it also leads to turf wars and a tendency to play to Kremlin prejudices. The West finds itself in a new “hot peace” in which many consider Russia not just as an irritant or challenge, but • While much useful intelligence is collected, as an outright threat. -

Of Kings and Pawns

OF KINGS AND PAWNS CHESS STRATEGY IN THE ENDGAME ERIC SCHILLER Universal Publishers Boca Raton • 2006 Of Kings and Pawns: Chess Strategy in the Endgame Copyright © 2006 Eric Schiller All rights reserved. Universal Publishers Boca Raton , Florida USA • 2006 ISBN: 1-58112-909-2 (paperback) ISBN: 1-58112-910-6 (ebook) Universal-Publishers.com Preface Endgames with just kings and pawns look simple but they are actually among the most complicated endgames to learn. This book contains 26 endgame positions in a unique format that gives you not only the starting position, but also a critical position you should use as a target. Your workout consists of looking at the starting position and seeing if you can figure out how you can reach the indicated target position. Although this hint makes solving the problems easier, there is still plenty of work for you to do. The positions have been chosen for their instructional value, and often combined many different themes. You’ll find examples of the horse race, the opposition, zugzwang, stalemate and the importance of escorting the pawn with the king marching in front, among others. When you start out in chess, king and pawn endings are not very important because usually there is a great material imbalance at the end of the game so one side is winning easily. However, as you advance through chess you’ll find that these endgame positions play a great role in determining the outcome of the game. It is critically important that you understand when a single pawn advantage or positional advantage will lead to a win and when it will merely wind up drawn with best play. -

1999/1 Layout

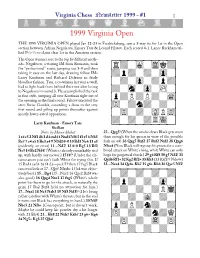

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #1 1 1999 Virginia Open THE 1999 VIRGINIA OPEN played Jan 22-24 in Fredricksburg, saw a 3-way tie for 1st in the Open section between Adrian Negulescu, Emory Tate & Leonid Filatov. Each scored 4-1. Lance Rackham tal- 1 1 lied 5 ⁄2- ⁄2 to claim clear 1st in the Amateur section. The Open winners rose to the top by different meth- ‹óóóóóóóó‹ ods. Negulescu, a visiting IM from Rumania, took õÏ›‹Ò‹ÌÙ›ú the “professional” route, jumping out 3-0 and then taking it easy on the last day, drawing fellow IMs õ›‡›‹›‹·‹ú Larry Kaufman and Richard Delaune in fairly bloodless fashion. Tate, a co-winner last year as well, õ‹›‹·‹›‡›ú had to fight back from behind this time after losing to Negulescu in round 3. He accomplished the task õ›‹Â‹·‹„‹ú in fine style, jumping all over Kaufman right out of õ‡›fi›fi›‹Ôú the opening in the final round. Filatov executed the semi Swiss Gambit, conceding a draw in the very õfl‹›‰›‹›‹ú first round and piling up points thereafter against mostly lower-rated opposition. õ‹fl‹›‹Áfiflú õ›‹›‹›ÍÛ‹ú Larry Kaufman - Emory Tate Sicilian ‹ìììììììì‹ Notes by Macon Shibut 25...Qxg5! (When the smoke clears Black gets more 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 f3 e5 6 Nb3 than enough for his queen in view of the possible Be7 7 c4 a5 8 Be3 a4 9 N3d2 0-0 10 Bd3 Nc6 11 a3 fork on e4) 26 Qxg5 Rxf2 27 Rxf2 Nxf2 28 Qxg6 (evidently an error) 11...Nd7! 12 0-0 Bg5 13 Bf2 Nfxe4 (Now Black will regroup his pieces for a com- Nc5 14 Bc2 Nd4! (White is already remarkably tied bined attack on White’s king, while White can only up, with hardly any moves.) 15 f4!? (Under the cir- hope for perpetual check.) 29 g4 Rf8 30 g5 Nd2! 31 cumstances you can’t fault White for trying this. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”. -

Course Notes and Summary

FM Morefield’s Chess Curriculum: Course Review This PDF is intended to be used as a place to review the topics covered in the course and should not be used as a replacement. Feel free to save, print, or distribute this PDF as needed. Section 1: Background Information History ● Chess is widely assumed to have originated in India around the seventh century. ● Until the mid-1400s in Europe, chess was known as shatranj, which had different rules than modern chess. ● Some well-known authors and chess players from that time period are Greco, Lucena, and Ruy Lopez. ● The Romantic Era lasted from the late 18th century until the middle of the 19th century, and was characterized by sacrifices and aggressive play. ● Chess has widely been considered a sport since the late 1800s, when the World Chess Championship was organized for the first time. Other ● Chess is considered a game of planning and strategy because it is a game with no hidden information, where you and your opponent have the same pieces, so there is no luck. ● Studying chess seriously can bring you many benefits, but simply playing it won’t make you smarter. Section 2: Rules of the Game Setting Up the Board ● There are sixty-four squares on the board, and thirty-two pieces (sixteen per player). ● Each player’s pieces are made up of eight pawns, two knights, two bishops, two rooks, a queen, and a king. ● There are two players, Black and White. White moves first. ● If you’re using a physical board, rotate the board until there is a light square on the bottom right for each player. -

Basicxqcheckmate.Pdf

PDF created with pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Preface The game of Xiangqi is similar to the deployment of forces for military operation. Though it is a battle on xiangqi board, its theory is similar to the military strategy and tactics. As it is stipulated by the xiangqi rules, the side that captures the opponent's King will be the winner of the game. Therefore, each side tries to outwit his opponent and strives to show his bravery in taking various kinds of checkmate methods and to do his best to seize every opportunity for winning the victory. The game of xiangqi is rendered with a mysterious hue. Nearly all xiangqi players or fans understand that the checkmate method takes an important position in the xiangqi game. However, some of the players believe that "the checkmate method can only play its roles in the end game." But in reality, we often see that in the heat-fought mid-game, being eager to achieve a quick success and instant benefit, one side often neglects to defend his own King, offering the opponent an opportunity for making a counterattack or winning the game. Although sometimes, a player has a chance to take a successive checkmate, as he is rusty on the checkmate methods, he bungles a chance of winning the battle, or loses the game. Such cases are often seen in actual competitions. And there are numerous examples showing that some players take advantage of checkmate methods in seizing opponent's pieces. In fact, the checkmate methods play a very important role, directly or indirectly, not only in the end game, but also in the mid-game, even in the entire game. -

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

Title 34 Elections Chapter 18 Initiative and Referendum

TITLE 34 ELECTIONS CHAPTER 18 INITIATIVE AND REFERENDUM ELECTIONS 34-1801. STATEMENT OF LEGISLATIVE INTENT AND LEGISLATIVE PURPOSE. The legislature of the state of Idaho finds that there have been incidents of fraudulent and misleading practices in soliciting and obtaining signatures on initiative or referendum petitions, or both, that false signatures have been placed upon initiative or referendum petitions, or both, that diffi- culties have arisen in determining the identity of petition circulators and that substantial danger exists that such unlawful practices will or may con- tinue in the future. In order to prevent and deter such behavior, the legis- lature determines that it is necessary to provide easy identity to the public of those persons who solicit or obtain signatures on initiative or referen- dum petitions, or both, and of those persons for whom they are soliciting and obtaining signatures and to inform the public concerning the solicitation and obtaining of such signatures. It is the purpose of the legislature in en- acting this act to fulfill the foregoing statement of intent and remedy the foregoing practices. [34-1801, added 1997, ch. 266, sec. 2, p. 758.] 34-1801A. PETITION. (1) An initiative petition shall embrace only one (1) subject and matters properly connected with it. (2) The following shall be substantially the form of petition for any law proposed by the initiative: WARNING It is a felony for anyone to sign any initiative or referendum petition with any name other than his own, or to knowingly sign his name more than once for the measure, or to sign such petition when he is not a qualified elector. -

Conclusion: from Strategic Stalemate to Strategic Initiative

Conclusion: From Strategic Stalemate to Strategic Initiative Shlomo Brom, Udi Dekel, and Anat Kurz The end of 2014 witnessed a change in Israel’s regional status and discredited one of Israel’s fundamental policy assumptions – that it is possible to stand on the sidelines and build a protective wall to prevent the spillover of regional unrest into its borders. Operation Protective Edge in Gaza; the rise of “lone wolf” terror activity in the West Bank; clashes between Palestinians and Israeli security forces and civilians on the Temple Mount; the formation of the Islamic State in the ISIS-occupied areas of Iraq and Syria; the inspiration that the group provides for jihadist groups and individuals throughout the Middle East; the discovery of ISIS-loyal jihad organizations and cells within Israel and near its borders – all these attest to the need to formulate an updated policy in line with local and regional trends and developments. In contrast with assessments sounded last year, whereby 2014 would !!" #$%#['(%)"*!+!,-./!%) "#%")0!")1-"/(#%"# 2! "-%"3 4(!,R "%()#-%(," security agenda – the P5+1-Iran nuclear negotiations and Israel-Palestinian negotiations – the year ended without marking any change on these fronts: the status quo in the Iran negotiations continued, and the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations were totally frozen. However, other surprising developments occurred over the course of 2014, led by the escalation between Hamas and Israel culminating in a war, and the conquests by ISIS and its expanded This chapter was formulated in conjunction with Maj. Gen. (ret.) Amos Yadlin. 187 Shlomo Brom, Udi Dekel, and Anat Kurz #%\2!%'!7"8-4!-+!49")0!"(: !%'!"-;"(%"!%*$(/!"'-%)#%2! ")-"'0(4(')!4#<!" the regional upheavals, especially the Syrian civil war, the recurring losses of the Iraqi army to ISIS forces, and the continued lack of stability and near-crumbling of the state framework in Libya and Yemen.