A Study of the Fox : D. H. Lawrence's Idea of Duality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Captain's Doll

A Study of The Captain’s Doll 論 文 A Study of The Captain’s Doll: A Life of “a Hard Destiny” YAMADA Akiko 要 旨 英語題名を和訳すると,「『大尉の人形』研究──「厳しい宿命」の人 生──」になる。1923年に出版された『大尉の人形』は『恋する女たち』, 『狐』及び『アルヴァイナの堕落』等の小説や中編小説と同じ頃に執筆さ れた D. H. ロレンスの中編小説である。これらの作品群は多かれ少なかれ 類似したテーマを持っている。 時代背景は第一次世界大戦直後であり,作品の前半の場所はイギリス軍 占領下のドイツである。主人公であるヘプバーン大尉はイギリス軍に所属 しておりドイツに来たが,そこでハンネレという女性と恋愛関係になる。し かし彼にはイギリスに妻子がいて,二人の情事を噂で聞きつけた妻は,ドイ ツへやってきて二人の仲を阻止しようとする。妻は,生計を立てるために人 形を作って売っていたハンネレが,愛する大尉をモデルにして作った人形 を見て,それを購入したいと言うのだが,彼女の手に渡ることはなかった。 妻は事故で死に,ヘプバーンは新しい人生をハンネレと始めようと思う が,それはこれまでの愛し愛される関係ではなくて,女性に自分を敬愛し 従うことを求める関係である。筆者は,本論において,この関係を男性優 位の関係と捉えるのではなくて,ロレンスが「星の均衡」の関係を求めて いることを論じる。 キーワード:人形的人間,月と星々,敬愛と従順,魔力,太陽と氷河 1 愛知大学 言語と文化 No. 38 Introduction The Captain’s Doll by D. H. Lawrence was published in 1923, and The Fox (1922) and The Ladybird (1923) were published almost at the same time. A few years before Women in Love (1920) and The Lost Girl (1921) had been published, too. These novellas and novels have more or less a common theme which is the new relationship between man and woman. The doll is modeled on a captain in the British army occupying Germany after World War I. The maker of the doll is a refugee aristocrat named Countess Johanna zu Rassentlow, also called Hannele, a single woman. She is Captain Hepburn’s mistress. His wife and children live in England. Hannele and Mitchka who is Hannele’s friend and roommate, make and sell dolls and other beautiful things for a living. Mitchka has a working house. But the captain’s doll was not made to sell but because of Hannele’s love for him. The doll has a symbolic meaning in that he is a puppet of both women, his wife and his mistress. -

The Short Story in English Les Cahiers De La Nouvelle

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 68 | Spring 2017 Special Issue: Transgressing Borders and Borderlines in the Short Stories of D.H. Lawrence Transgression in The Fox Jacqueline Gouirand-Rousselon Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/1836 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 June 2017 Number of pages: 101-113 ISBN: 978-2-7535-6516-6 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference Jacqueline Gouirand-Rousselon, « Transgression in The Fox », Journal of the Short Story in English [Online], 68 | Spring 2017, Online since 01 June 2019, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/jsse/1836 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved Transgression in The Fox 1 Transgression in The Fox Jacqueline Gouirand-Rousselon 1 D. H. Lawrence had just finished Psychoanalysis of the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious and rewritten a number of short stories when he “put a long tail” to The Fox, adding the two dreams, the killing of the fox and of Banford. These changes took place between December 1921 and February 1922. To The Fox and The Ladybird, The Captain’s Doll was added, the three novellas being collected in one book published in 1923. Their aesthetic quality may have been one of the reasons for publishing them in one volume. “So modern, so new, a new manner,” Lawrence wrote to Seltzer. The Fox is the longer and different version of a shorter tale written in November 1918 at Hermitage (Berkshire) and cut for magazine publication in The Dial (1919). -

{FREE} the Fox / the Captains Doll / the Ladybird

THE FOX / THE CAPTAINS DOLL / THE LADYBIRD: WITH THE CAPTAINS DOLL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK D. H. Lawrence,Helen Dunmore,Dieter Miehl,David Ellis | 272 pages | 01 Dec 2006 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141441832 | English | London, United Kingdom The Fox / The Captains Doll / The Ladybird: WITH The Captains Doll PDF Book Article Preview :. Sound Mix: Mono. Published by Penguin Non-Classics. Photos Add Image. Lawrence; Edited with an introduction by Edward D. Lawrence's brilliant and insightful evocation of human relationships - both tender and cruel - and the devastating results of war. Crowd sourced content that is contributed to World Heritage Encyclopedia is peer reviewed and edited by our editorial staff to ensure quality scholarly research articles. Forster, in an obituary notice, challenged this widely held view, describing him as "the greatest imaginative novelist of our generation. Color: Color. Runtime: 67 min. Mcdonald Copies for Sale Lawrence, D. Like, something's missing. These texts have received less attention than Lawrence's earlier writing, and Balbert's provocative readings are welcome additions to the critical record. Rananim and the social revolution. Leavis championed both his artistic integrity and his moral seriousness, placing much of Lawrence's fiction within the canonical "great tradition" of the English novel. Congress, E-Government Act of Sign in with your eLibrary Card close. General editors preface. Get social Connect with the University of Nottingham through social media and our blogs. Lawrence Penguin Lawrence Edition. Pages are cancel pages with modified text; copies printed. Lawrence Birthplace Museum D. The Fox / The Captains Doll / The Ladybird: WITH The Captains Doll Writer Book Club of California, San Francisco User Reviews. -

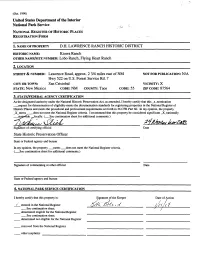

Taos CODE: 55 ZIP CODE: 87564

(Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. NAME OF PROPERTY D.H. LAWRENCE RANCH HISTORIC DISTRICT HISTORIC NAME: Kiowa Ranch OTHER NAME/SITE NUMBER: Lobo Ranch, Flying Heart Ranch 2. LOCATION STREET & NUMBER: Lawrence Road, approx. 2 3/4 miles east of NM NOT FOR PUBLICATION: N/A Hwy 522 on U.S. Forest Service Rd. 7 CITY OR TOWN: San Cristobal VICINITY: X STATE: New Mexico CODE: NM COUNTY: Taos CODE: 55 ZIP CODE: 87564 3. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_nomination __request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _X_nationally ^locally. (__See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official Date State Historic Preservation Officer State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property __meets does not meet the National Register criteria. (__See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that this property is: Signature of the Keeper Date of Action . entered in the National Register c f __ See continuation sheet. / . determined eligible for the National Register __ See continuation sheet. -

The Cambridge Edition of the Letters and Works of D. H. Lawrence

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-36607-6 - The Virgin and the Gipsy and Other Stories D. H. Lawrenc Edited by Michael Herbert, Bethan Jones and Lindeth Vasey Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE EDITION OF THE LETTERS AND WORKS OF D. H. LAWRENCE © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-36607-6 - The Virgin and the Gipsy and Other Stories D. H. Lawrenc Edited by Michael Herbert, Bethan Jones and Lindeth Vasey Frontmatter More information THE WORKS OF D. H. LAWRENCE EDITORIAL BOARD general editor James T. Boulton M. H. Black Paul Poplawski John Worthen © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-36607-6 - The Virgin and the Gipsy and Other Stories D. H. Lawrenc Edited by Michael Herbert, Bethan Jones and Lindeth Vasey Frontmatter More information THE VIRGIN AND THE GIPSY AND OTHER STORIES D. H. LAWRENCE edited by MICHAEL HERBERT BETHAN JONES and LINDETH VASEY © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-36607-6 - The Virgin and the Gipsy and Other Stories D. H. Lawrenc Edited by Michael Herbert, Bethan Jones and Lindeth Vasey Frontmatter More information cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521366076 This, the Cambridge Edition of the text of The Virgin and the Gipsy and Other Stories, is established from the original sources and first published in 2005, © the Estate of Frieda Lawrence Ravagli 2005. -

The Ladybird Novellas: D.H. Lawrence's Use of Mythic and Realistic Components

D.H. LAWRENCE'S LADYBIRD NOVELLAS THE LADYBIRD NOVELLAS: D.H. LAWRENCE'S USE OF MYTHIC AND REALISTIC COMPONENTS By LISA BRITT ANDERSON, B.A., B.Ed. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University September 1988 MASTER OF ARTS (1988) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Ladybird Novellas: D.H. Lawrence's Use of Mythic and Realistic Components AUTHOR: Lisa Britt Anderson, B.A. (Trent University) B.Ed. (University of Toronto) SUPERVISOR: Professor Ronald Granofsky NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 87 ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines three novellas by D.H. Lawrence: The Ladybird, The Fox, and The Captain's Doll, collectively referred to as the Ladybird tales. It approaches these works with the intention of demonstrating the fundamental role played therein by mythic and realistic narrative components, and also with the intention of pointing out the excessively manipulative way that Lawrence uses these components to give voice to his didactic philosophy. In the study's Introduction, the terms 'mythic component' and 'realistic component' are defined, and their applicability to Lawrence's fiction is explained. Lawrence's own definition of authorial immorality is then explored, and the study's primary argument, that Lawrence's use of mythic and realistic components in the Ladybird tales is immoral by his own standards, is stated. Each of the three chapters is devoted to supporting this argument as it pertains to one of the Ladybird novellas. It is hoped that this thesis will create an awareness that the world-view presented in the Ladybird novellas is not so much an integral part of the art as it is an imposition on the art by the author. -

THE SPIRIT of D. H. LAWRENCE the Spirit of D

THE SPIRIT OF D. H. LAWRENCE The Spirit of D. H. La-wrence Centenary Studies Edited by Gamini Salgado sometime Professor of English University of Exeter and G. K. Das Professor of English University of Delhi Foreword by Raymond Williams M MACMILLAN PRESS ©the Estate of Gamini Salgado and G. K. Das 1988 Foreword© Raymond Williams 1988 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1988 978-0-333-34159-9 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1956 (as amended). Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1988 Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world Typeset by Wessex Typesetters (Division of The Eastern Press Ltd) Frome, Somerset British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data The spirit of D. H. Lawrence: centenary studies. 1. Lawrence, D. H.- Criticism and interpretation I. Salgado, Gamini II. Das, G. K. 823'.912 PR6023.A93Z/ ISBN 978-1-349-06512-7 ISBN 978-1-349-06510-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-06510-3 Contents Foreword Raymond Williams vii Preface G. K. Das xiii Acknowledgements xv Notes on the Contributors xvii 1 Lawrence's Autobiographies John Worthen 1 2 'The country of my heart': D. H. Lawrence and the East Midlands Landscape J. -

The Fox by D.H Lawrence

Dr. Vibhas Ranjan Assistant professor, Department of English Patna College, Patna University Contact details: +91- 7319932414 [email protected] For B.A English Hons. Part-2; Paper-4 The Fox by D.H Lawrence D.H Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) ,described as “the greatest imaginative novelist of our generation” by E.M Forster, is a prominent literary figure of the twentieth century. He was a versatile literary talent who penned all time hit novels like Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow, Women in Love and Lady Chatterley’s Lover. He composed nearly 800 poems and wrote plays like The Daughter-in-Law. His critical works include Studies in Classic American Literature. His genius is also reflected in his painting works. Lawrence working class background and the tensions between his parents provided the raw material for a number of his works. Exploring issues of sexuality, vitality, spontaneity , instinct and emotional health , his collected works represent an extended reflection upon the dehumanizing effects of modernity. He wrote passionately against what he called “the cerebralization of feeling”. He attempts to show “ the real flame of feelings” in his literary creations. As a realist, Lawrence uses his characters to give form to his personal philosophy which also includes his depiction of sexuality. He is viewed as a leader of modernist English literature and considered a visionary thinker. He studied and admired New England Transcendentalism, particularly the works of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Louisa May Alcott. 1 D.H Lawrence is also reputed as a prolific short-story writer. He has written nearly seventy short stories which include ‘The Prussian Officer’ , ‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’, ’The Fox’, ‘The White Stocking’ and ‘The Woman Who Rode Away’ as well as many lesser known works. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The sleeping beauty motif in the short stories of D. H. Lawrence Backhouse, J. L. How to cite: Backhouse, J. L. (1969) The sleeping beauty motif in the short stories of D. H. Lawrence, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10079/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk AJjaTRACT OF THESIS 'jitle; The Sleeping Beauty l>iotif in the bhort Stories of J.H. Lav/renoe. by J.L. Backhouse, B.A. In this thesis, ten tales covering almost the whole of D.H. Lawrence's writing career have been analysed in terms of the 'Sleeping Beauty' motif or "the myth of the. awakened sleeper" - a motif which has heen noted briefly in Lawrence's fiction by several critics. Chapter One begins with a discussion of the Sleeping Beauty legend, its origins and its variants, and leads on to a comparison and contrast of two early tales. -

THE Edinburgh Companion to DH LAWRENCE and the ARTS

The Edinburgh Companion to D. H. Lawrence and the Arts 66511_Brown511_Brown aandnd RReid.inddeid.indd i 225/09/205/09/20 33:38:38 PPMM Edinburgh Companions to Literature and the Humanities Published The Edinburgh Companion to Fin de Siècle The Edinburgh Companion to Virginia Woolf Literature, Culture and the Arts and the Arts Edited by Josephine M. Guy Edited by Maggie Humm The Edinburgh Companion to Animal Studies The Edinburgh Companion to Twentieth-Century Edited by Lynn Turner, Undine Sellbach and Literatures in English Ron Broglio Edited by Brian McHale and Randall Stevenson The Edinburgh Companion to Contemporary A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Narrative Theories Literatures in English Edited by Zara Dinnen and Robyn Warhol Edited by David Johnson and Prem Poddar The Edinburgh Companion to Anthony Trollope A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Edited by Frederik Van Dam, David Skilton and Literatures – Continental Europe and its Ortwin Graef Empires The Edinburgh Companion to the Short Story Edited by Prem Poddar, Rajeev Patke and in English Lars Jensen Edited by Paul Delaney and Adrian Hunter The Edinburgh Companion to Twentieth- The Edinburgh Companion to the Postcolonial Century British and American War Literature Middle East Edited by Adam Piette and Mark Rowlinson Edited by Anna Ball and Karim Mattar The Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and The Edinburgh Companion to Ezra Pound and the Arts the Arts Edited by Mark Thornton Burnett, Adrian Edited by Roxana Preda Streete and Ramona Wray The Edinburgh Companion to Elizabeth Bishop The Edinburgh Companion to Samuel Beckett Edited by Jonathan Ellis and the Arts The Edinburgh Companion to Gothic and the Edited by S. -

D. H. Lawrence and the Bible

D. H. LAWRENCE AND THE BIBLE T. R. WRIGHT published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb22ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain # T. R. Wright 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in Great Britain at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Baskerville 11/12.5pt ce A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 78189 2 hardback Contents Abbreviations page vi Acknowledgements ix 1 `The Work of Creation': Lawrence and the Bible 1 2 Biblical intertextuality: Bakhtin, Bloom and Derrida 14 3 Higher criticism: Lawrence's break with Christianity 21 4 Poetic fathers: Nietzsche and the Romantic tradition 36 5 Pre-war poetry and ®ction: Adam and Eve come through 57 6 Re-marking Genesis: The Rainbow as counter-Bible 84 7 Double-reading the Bible: Esoteric Studies and Re¯ections 110 8 Genesis versus John: Women in Love, The Lost Girl and 129 Mr Noon 9 Books of Exodus: Aaron's Rod, Kangaroo and The Boy in 140 the Bush 10 Prose Sketches, `Evangelistic Beasts' and Stories with 162 biblical `Overtones' 11 Prophetic voices and `red' mythology: The Plumed Serpent 188 and David 12 The Risen Lord: The Escaped Cock, Lady Chatterley's Lover 214 and the Paintings 13 Apocalypse: the con¯ict of love and power 228 14 Last Poems: ®nal thoughts 245 List of references 252 Indices 264 v Abbreviations All references to Lawrence's work, unless otherwise stated, are to the Cambridge Edition of the Letters and Works of D. -

The Captain's Doll”

A Comedy of Errors―D. H. Lawrence's “The Captain's Doll” 著者 TERADA Akio journal or Memoirs of the Muroran Institute of publication title Technology. Cultural science volume 37 page range 49-80 year 1987-11-10 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10258/711 A Comedy of Errors -D. H. Lawrence's “The Captain's Doll" Akio Terada Abstract O.H. O.H. Lawrence's three novellas ,“ The Fox ,"“ The Ladybird" and “The Captain's 0011 ," were meaningfully published in one volume in 1923. These works have many elements in common: objective style; title images; demon levers; open ending; and disordered rela tionships tionships between sexes and the theme of resurrection. But the narratives and devices through through which the thematic development is actualized have a wide range of variety. The present present essay will single “The Captain's Ooll" out from the three , touching upon the other two if necessary “The Captain's 0011 ," as is often with Lawrence's fiction , has been ex- posed posed to unfavourable comments with the exception of a handful of critics like F.R. Leavis who highly values this novella in his two books. Curiously enough , most commentators have have pointed out its comic aspect but their treatments are done at a serious leve l. Charac teristic teristic is its lightness sustained throughout this tale. As a work of pure comedy emphasis is is here laid upon the minute analysis of principal actors which 1 believe is of much use to accept accept the ending as a proper one. The story is written in an objective style , with the au- thor thor detached from his discursive doctorine.