Ecology and Recovery Allegheny County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

N N E W S L E T T E

WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA MUSHROOM CLUB n NEWSLETTERn Volume 16, Issue 2 MAY / JUNE 2016 16th Annual Lincoff Foray: President’s Message Saturday, September 24, 2016 RICHARD JACOB THE 16TH ANNUAL Gary Lincoff Foray will be held at The WPMC President Rose Barn in Allegheny County’s North Park. This year’s program will be a single-day event featuring Gary I HAVE BEEN WATCHING THE Lincoff, author of the Audubon Guide to Mushrooms of North MorelHunters.com sightings map, in America, The Complete Mushroom Hunter, The Joy of Forag- anticipation of the first of this sea- ing, and many others. This year we are delighted to have as son’s morels. The first morel sighting our Guest Mycologist Dr. Nicholas Money, author of Mush- in our area at the end of March was rooms, The Triumph of the Fungi and Mr. Bloomfield’s Orchard: not on the MorelHunters website but The Mysterious World of Mushrooms, Molds and Mycologists. on our Facebook Group page, reported by Bob Sleigh, host of Nik will present “The Birth, Life, and Extraordinary Death of WPMC’s Morel Mushroom Walk with Indiana County Friends of a Mushroom Spore.” In addition, WPMC President Richard the Parks on April 30. Bob wrote “Second time to find morels Jacob will present an update of our DNA barcoding program. in PA in March. If the weather holds, next weekend should be The day will include guided walks, mushroom identification the time to start some serious hunting.” Alas, the next week tables, a cooking demo with Chef George Harris, sales table, was cool, with snow on the ground and freezing temperatures authors’ book signing, auction and, of course, the legendary at night. -

Knickzones in Southwest Pennsylvania Streams Indicate Accelerated Pleistocene Landscape Evolution

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2020 Knickzones in Southwest Pennsylvania Streams Indicate Accelerated Pleistocene Landscape Evolution Mark D. Swift West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Geomorphology Commons Recommended Citation Swift, Mark D., "Knickzones in Southwest Pennsylvania Streams Indicate Accelerated Pleistocene Landscape Evolution" (2020). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7542. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7542 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Knickzones in Southwest Pennsylvania Streams Indicate Accelerated Pleistocene Landscape Evolution Mark D. Swift Thesis Submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Geography Jamison Conley, Ph.D., Co-Chair J. Steven Kite, Ph.D., Co-Chair Nicolas Zegre, Ph.D. Department of Geology and Geography Morgantown, West Virginia 2020 Keywords: landscape evolution, knickzone, southwest Pennsylvania Copyright 2020 Mark D. -

Newsletter Content

VISTAS AN ALLEGHENY LAND TRUST PUBLICATION | 2017 Q1 Newsletter Content A YEAR IN REVIEW: 2016 2 ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION TEAM & DMH NEWS 3 DONOR RECOGNITION LIST, JOIN OUR BOARD 4-8 NOTES FROM THE LAND 9 EVENTS CALENDAR 10 MEET A STEWARD 11 2016: A Year to Remember by Chris Beichner | President & CEO We won’t soon forget 2016. Just looking at the infographic tells a ALLEGHENY LAND TRUST lot about our accomplishments over the past year. We were busy. 2016 IN REVIEW We accomplished a lot. We are happy with our results. But, the statistics do not tell the entire story, and we’re certainly not done reaching for our goals. Here are a few other ways that made 2016 4 NEW CONSERVATION OF 121 a year we won’t soon forget. AREAS ACRES In August 2016, ALT was officially notified of our national re-ac- protecting sequestering absorbing creditation status by the Land Trust Accreditation Commission. Out of 1,700 land trusts nationwide, we are only one of 350 land CO2 trusts that are nationally accredited. The accreditation status sig- nifies to landowners, funders, and partners that we are committed 40,000 Trees 500,000 lbs 104M gal. of Carbon of Rainwater to a high standard of excellence in all aspects of our operations ALT’s volunteered donated and programming. We began our re-accreditation process in 2015, five years af- ter the original accreditation. It took us 18 months, five rounds of review, and more than 400 hours of time to complete the “audit” 574 5,039 $115,903 Volunteers Hours of In-Kind review of our communication, documentation, and decision pro- Investment cesses. -

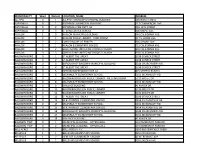

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION NAME ADDRESS

MUNICIPALITY Ward District LOCATION_NAME ADDRESS ALEPPO 0 1 ALEPPO TOWNSHIP MUNICIPAL BUILDING 100 NORTH DRIVE ASPINWALL 0 1 ASPINWALL MUNICIPAL BUILDING 217 COMMERCIAL AVE. ASPINWALL 0 2 ASPINWALL FIRE DEPT. #2 201 12TH STREET ASPINWALL 0 3 ST SCHOLASTICA SCHOOL 300 MAPLE AVE. AVALON 1 0 AVALON MUNICIPAL BUILDING 640 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 2 1 AVALON PUBLIC LIBRARY - CONF ROOM 317 S. HOME AVE. AVALON 2 2 LORD'S HOUSE OF PRAYER 336 S HOME AVE AVALON 3 1 AVALON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 721 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 2 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. AVALON 3 3 GREENSTONE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 939 CALIFORNIA AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 1 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 2 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 3 BOROUGH OF BALDWIN MUNICIPAL BUILDING 3344 CHURCHVIEW AVE. BALDWIN BORO 0 4 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 5 OPTION INDEPENDENT FIRE CO 825 STREETS RUN RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 6 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 7 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY - MEETING ROOM 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 8 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 9 WALLACE BUILDING 41 MACEK DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 10 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 11 BALDWIN BOROUGH PUBLIC LIBRARY 5230 WOLFE DR BALDWIN BORO 0 12 ST ALBERT THE GREAT 3198 SCHIECK STREET BALDWIN BORO 0 13 W.R. PAYNTER ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 3454 PLEASANTVUE DR. BALDWIN BORO 0 14 MCANNULTY ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 5151 MCANNULTY RD. BALDWIN BORO 0 15 W.R. -

Brentwood Comprehensive Plan

THE BOROUGH OF BRENTWOOD James H. Joyce - Mayor (1981 - 1997) Ronald A. Amoni,- Mayor (1998-2001) Brentwood Borouph Council (1994 - 1997) Brentwood Borouyh Council (1998 - 2001) Fred A Swanson - President Nancy Patton - President Nancy Patton - Vice President Scott Werner -Vice President Sonya C. Vernau David K. Schade Ronald A. Arnoni Raymond J. Schiffhauer Michael A. Caldwell Marie Landon David K. Schade Martin Vickless Raymond J. Schiffhauer Deborah E. Takach Borough Solicitor: James Perich, Esq. Borough Engineer: George Pitcher, Neilan Engineers Brentwood Administrative Office: Elvina Nicola Borough Treasurer: James L. Myron Brentwood Tax Office: Katherine Gannis Brentwood Police Department: George Swinney Brentwood Public Works Department: Thomas Kammermeier Brentwood Library: Monica Stoicovy Brentwood Borouph Planninp Commission Brenhvood Zoning HearinP Board Jerry Borst - Chairman Edward Szpara - Chairman Janice Iwanonkiw - Vice Chairperson Phil Hoebler - Vice Chairman Michael Means Robert Haas Michael Wooten Joanna McQuaide Rick Cerminaro Robert Hartshorn Sally Bucci Emanuel Perry Solicitor: Alan Shuckrow, Esq. Information Compiled and Supplied bv the Followinp: Brentwood Borough Council Brentwood Borough Planning Coinmission Brentwood Borough Citizen’s Advisory Committee Ilrcntwood Ilorough School District Ilrciit wood I3oroiigli Ilislorical Socicly Ilrcii~wood11oro1igIi Voliiiiiccr Fire I )cprirtiiiciil I~rciiiwoodIicoiioiiiic I)cvclopiiicii~ ( ‘orporiilioii Part I: THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Section 1: Introduction / Vision Statement -

Carrick Survey Report

Architectural Inventory for the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania Planning Sector 5: South Pittsburgh Carrick Neighborhood Report of Findings and Recommendations The City of Pittsburgh In Cooperation With: Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission October 2016 Prepared By: Michael Baker International, Inc. Jesse A. Belfast and Clio Consulting: Angelique Bamberg with Cosmos Technologies, Inc. Suraj Shrestha, E.I.T. The Architectural Inventory for the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, was made possible with funding provided by the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office (PA SHPO), the City of Pittsburgh, and the U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Certified Local Government program. The contents and opinions contained in this document do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. This program receives federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service; 1849 C Street N.W.; Washington, D.C. 20240. 4 | P a g e abstract Abstract This architectural inventory for the City of Pittsburgh (Planning Sector 5: Carrick Neighborhood) is in partial fulfillment of Preserve Policy 1.2, to Identify and Designate Additional Historic Structures, Districts, Sites, and Objects (City of Pittsburgh Cultural Heritage Plan, 2012). -

Rediscovering

June 2011 REDISCOVERING... Community Connections Competitiveness Char-West Multi-Municipal Comprehensive Plan McKees Rocks Borough, Neville Township and Stowe Township TABLE OF CONTENTS | Acknowledgements .............................................. v Foreword ............................................................. xi Part 1: Overview .................................................. 1 Introduction ................................................... 3 Planning Approach and Process ................... 5 Public Participation ........................................ 7 Part 2: Foundations ............................................. 9 Opportunities and Challenges ..................... 11 Other Considerations .................................. 15 Part 3: Vision ..................................................... 19 Introduction ................................................. 21 Goals ........................................................... 21 Objectives ................................................... 22 Places to Grow ............................................ 22 Recommendations ...................................... 23 Future Land Use and Housing Plan ......... 24 Transportation, Infrastructure and Energy Plan ......................................................... 37 Business, Community and Economic Development Plan ................................... 61 Environment and Culture Plan ................. 85 Civic Amenities Plan ................................ 93 Places to Grow ..................................... -

An Allegheny Land Trust Publication Summer 2021

NOTES FROM THE LAND COMMUNITY CONSERVATION WHERE ARE WE NOW? FUTURE OF OUR FORESTS Saving Green Space Together Our Projects in Action A Map of ALT Projects Study of Barking Slopes 2 4 8 12 VISTAn Allegheny Land Trust Publication SummerS 2021 VISTAS | 2021 SUMMER 1 notes FROM THE LAND: 303 Acres & the Hundreds of People Who Helped by Roy Kraynyk | VP of Land Protection & Capital Projects Children playing at Girty’s Woods in Reserve. Photo by Lindsay Dill. wo projects, 303 acres, 2.5 years, $3.8 million, and them to appreciate the value of locally-accessible green space. T 1,450 people is what ALT’s most recent land conserva- tion projects, Churchill Valley Greenway and Girty’s Woods, The 155-acre Girty’s Woods Conservation Area in Reserve represent. Township is one of our larger purchases in recent years. What makes Girty’s Woods unique is how close this much unde- There were several nail-biting moments and many sleepless veloped green space is to the city; it is approximately 3 miles nights along the way for ALT staff and grassroots organizers upstream from The Point on the Allegheny River. Unique who were closely engaged when both of these projects were in views of the city’s skyscrapers are available from the well-used jeopardy due to funding gaps and necessary contract exten- trails that meander over ridges and down slopes into the dense- sions. Fortunately, sellers of the lands provided the extensions ly-populated streets of Millvale. The value of this green space to that ALT needed. -

Cara Schneider (215) 599-0789, [email protected] Deirdre Childress Hopkins (215) 599-2291, [email protected] Tweet Us: @Visitphillypr

CONTACTS: Cara Schneider (215) 599-0789, [email protected] Deirdre Childress Hopkins (215) 599-2291, [email protected] Tweet Us: @visitphillyPR Tweet It: The how-tos of must-dos when you @visitphilly: https://vstphl.ly/2LMm5lA PHILLY 101: THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO NAVIGATING PHILADELPHIA Primer On The City’s Layout, Icons & Accents PHILADELPHIA, June 25, 2019 – Every year, visitors to Philadelphia get to know the city’s history, customs, cuisine, dialect and landscape during their visits. Both first-time travelers and returning natives discover and rediscover a diverse, neighborhood-based metropolis with a downtown that’s easy to navigate on one’s own or via public transit. Philly regularly receives raves in The New York Times, Bon Appétit, Travel + Leisure, USA Today and Condé Nast Traveler, yet doesn’t stand one bit for pretense. Here are the basics any visitor to Philadelphia should know: Well-Planned City: • Layout – Seventeenth-century city planner William Penn envisioned the grid of streets that comprise Philadelphia’s downtown, Center City. Perpendicular streets run north-south (they’re numbered) and east-west (many named for trees: Walnut, Locust, Spruce). What would be 1st Street is named Front Street. What would be 14th Street is Broad Street. Two rivers, the Schuylkill and the Delaware (dividing Pennsylvania from New Jersey), form the western and eastern boundaries of Center City; Vine Street and South Street form north-south boundaries. Today, Penn continues to give direction to the city. His statue atop City Hall points northeast. • Exceptions to the Layout – The 101-year-old, mile-long Benjamin Franklin Parkway cuts diagonally through Center City’s grid, from near City Hall, past the famous LOVE Park to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. -

Vistas 0910.Indd

A publication of Allegheny Land Trust Fall 2010 From the Sycamore Island Recommendations Executive Presented at Public Meeting Director Allegheny Land Trust (ALT) held a meeting at the Sylvan CONSERVING Canoe Club on September 9 to share the preliminary findings LAND… and recommendations of the Sycamore Island Management Plan. PRESERVING Recommendations focus on providing safe, interesting and COMMUNITY educational access for the public that does not harm the unique island habitat. Preliminary recommendations include: ALT’s approach to • Enhance habitat to protect over 100 birds including 30 accomplishing our mission species of breeding birds including regionally rare Carolina involves education, legislation chickadee and willow flycatcher (PA Wildlife Action Plan and acquisition. Species of Maintenance Concern), and promote greater Green space is as critical to diversity and abundance of migrant songbirds. the health and function of a • Address lack of amphibians and reptiles by improving community as libraries, roads, breeding habitat and protect island banks where the schools, commercial centers, unique spiny softshell turtle has been found. housing and other amenities. • Limit public access with one canoe/kayak landing and one ALT brings a conservation- low–impact public trail open during specific times of the centric perspective to year to protect habitats particularly for migratory birds, community land planning, over 30 species of fish and vulnerable freshwater mussels meaning that growth and “Sycamore Island”, continued on page 2 development should respond to the landscape rather than the More Inside: landscape being altered to What is this? accommodate growth. 2…Welcome new Board Green space should not be a Members token afterthought in a 3…Out in the Field municipality’s future planning but the foundation of natural 4 and 5...About ALT Conservation Areas infrastructure that supports a community’s distinctive 6...Tributes to John character, helps manage Hamm and David stormwater and provides respite Pencoske for humans and habitat for 7…Mt. -

St. Louis Streets Index (1994)

1 ST. LOUIS STREETS INDEX (1994) by Dr. Glen Holt and Tom Pearson St. Louis Public Library St. Louis Streets Index [email protected] 2 Notes: This publication was created using source materials gathered and organized by noted local historian and author Norbury L. Wayman. Their use here was authorized by Mr. Wayman and his widow, Amy Penn Wayman. This publication includes city streets in existence at the time of its creation (1994). Entries in this index include street name; street’s general orientation; a brief history; and the city neighborhood(s) through which it runs. ABERDEEN PLACE (E-W). Named for the city of Aberdeen in north-eastern Scotland when it appeared in the Hillcrest Subdivision of 1912. (Kingsbury) ABNER PLACE (N-S). Honored Abner McKinley, the brother of President William McKinley, when it was laid out in the 1904 McKinley Park subdivision. (Arlington) ACADEMY AVENUE (N-S). The nearby Christian Brothers Academy on Easton Avenue west of Kingshighway was the source of this name, which first appeared in the Mount Cabanne subdivision of 1886. It was known as Cote Brilliante Avenue until 1883. (Arlington) (Cabanne) ACCOMAC BOULEVARD and STREET (E-W). Derived from an Indian word meaning "across the water" and appearing in the 1855 Third City Subdivision of the St. Louis Commons. (Compton Hill) ACME AVENUE (N-S). Draws its name from the word "acme", the highest point of attainment. Originated in the 1907 Acme Heights subdivision. (Walnut Park) ADELAIDE AVENUE (E-W & N-S). In the 1875 Benjamin O'Fallon's subdivision of the O'Fallon Estate, it was named in honor of a female relative of the O'Fallon family. -

(Pittsburgh Pool) on the Ohio, Allegheny, and Monongahela Rivers, and to the Pools of Dams #2 and #3 on the Monongahela River

Aquatic Invertebrate Biological Assessments Phases 1 & 2 - 2001 AQUATIC INVERTEBRATE BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENTS Phase 1, Interim Report, October 2001 BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF AQUATIC INVERTEBRATE COMMUNITIES OF STREAMS TRIBUTARY TO THE EMSWORTH DAM POOL (PITTSBURGH POOL) ON THE OHIO, ALLEGHENY, AND MONONGAHELA RIVERS, AND TO THE POOLS OF DAMS #2 AND #3 ON THE MONONGAHELA RIVER Prepared by: Michael Koryak, Limnologist Linda J. Stafford, Biologist U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Pittsburgh District 3 Rivers - 2nd Nature Studio for Creative Inquiry Carnegie Mellon University 3R2N Aquatic Invertebrate Biological Assessments, Phases 1 & 2 - 2001 For more information on the 3 Rivers – 2nd Nature Project, see http://3r2n.cfa.cmu.edu If you believe that ecologically healthy rivers are 2nd Nature and would like to participate in a river dialogue about water quality, recreational use and biodiversity in the 3 Rivers Region, contact: Tim Collins, Research Fellow Director 3 Rivers - 2nd Nature Project STUDIO for Creative Inquiry 412-268-3673 fax 268-2829 [email protected] Copyright © 2002 – Studio for Creative Inquiry, Carnegie Mellon All rights reserved Published by the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, Rm 111, College of Fine Arts, Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh PA 15213 412-268-3454 fax 268-2829 http://www.cmu.edu/studio First Edition, First Printing i 3R2N Aquatic Invertebrate Biological Assessments, Phases 1 & 2 - 2001 Co-Authors Tim Collins, Editor Partners in this Project 3 Rivers Wet Weather Incorporated (3RWW) Allegheny County Health Department (ACHD) Allegheny County Sanitary Authority (ALCOSAN) 3 Rivers - 2nd Nature Advisors Reviewing this Project John Arway Chief Environmental Services, PA Fish and Boat Commission Wilder Bancroft Environmental Quality Manager, Allegheny County Health Dept.