Full Spring 2009 Issue the .SU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

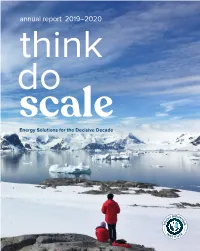

Annual Report 2019–2020

annual report 2019–2020 Energy Solutions for the Decisive Decade M OUN KY T C A I O N R IN S T E Rocky Mountain Institute Annual Report 2019/2020TIT U1 04 Letter from Our CEO 08 Introducing RMI’s New Global Programs 10 Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Contents. 2 Rocky Mountain Institute Annual Report 2019/2020 Cover image courtesy of Unsplash/Cassie Matias 14 54 Amory Lovins: Making the Board of Trustees Future a Reality 22 62 Think, Do, Scale Thank You, Donors! 50 104 Financials Our Locations Rocky Mountain Institute Annual Report 2019/2020 3 4 Rocky Mountain Institute Annual Report 2019/2020 Letter from Our CEO There is no doubt that humanity has been dealt a difficult hand in 2020. A global pandemic and resulting economic instability have sown tremendous uncertainty for now and for the future. Record- breaking natural disasters—hurricanes, floods, and wildfires—have devastated communities resulting in deep personal suffering. Meanwhile, we have entered the decisive decade for our Earth’s climate—with just ten years to halve global emissions to meet the goals set by the Paris Agreement before we cause irreparable damage to our planet and all life it supports. In spite of these immense challenges, when I reflect on this past year I am inspired by the resilience and hope we’ve experienced at Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI). This is evidenced through impact made possible by the enduring support of our donors and tenacious partnership of other NGOs, companies, cities, states, and countries working together to drive a clean, prosperous, and secure low-carbon future. -

Rodgers Family Papers

Rodgers Family Papers A Finding Aid to the Papers in the Naval Historical Foundation Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms011168 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm70052811 Prepared by Ruth S. Nicholson Collection Summary Title: Rodgers Family Papers Span Dates: 1788-1944 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1820-1930) ID No.: MSS52811 Creator: Rodgers family Extent: 15,500 items ; 60 containers plus 1 oversize ; 20 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Rodgers (Rogers) family. Correspondence, journals, drafts of writings and speeches, transcripts of radio broadcasts, book reviews, notes and notebooks, biographical material, and other papers relating chiefly to the naval careers of John Rodgers (1773-1838), John Rodgers (1812-1882), William Ledyard Rodgers (1860-1944), John Augustus Rodgers (1848-1933), and John Rodgers (1881-1926). Includes correspondence of the Hodge family, Matthew Calbraith Perry, Oliver Hazard Perry (1785-1819), and other relatives of the Rodgers family. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Agassiz, Louis, 1807-1873. Ammen, Daniel, 1820-1898. Bainbridge, William, 1774-1833. Benson, William Shepherd, 1855-1932. Brooke, John M. (John Mercer), 1826-1906. Buchanan, James, 1791-1868. -

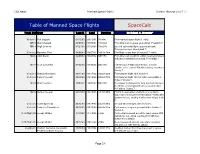

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

Points West Materials Once Said, “Man’S Mind, in Any Medium Or Format

BUFFALO BILL HISTORICAL CENTER n CODY, WYOMING n SPRING 2011 Thomas Moran n Karl May n Samuel Franklin Cody To the point ©2011 Buffalo Bill Historical Center (BBHC). Written permission liver Wendell Holmes is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials once said, “Man’s mind, in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are BBHC photos unless otherwise noted. Questions about image once stretched by a new rights and reproduction should be directed to Rights and idea,O never regains its original Reproductions, [email protected]. Bibliographies, works cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve dimensions.” space. However, such information is available by contacting the We here at the Buffalo Bill editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, BBHC, 720 Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414, or [email protected]. Historical Center couldn’t agree Senior Editor: more. In the last ten years, our Mr. Lee Haines minds have been stretched in Managing Editor: extraordinary directions, and none Ms. Marguerite House of us has ever been the same. Assistant Editor: Ms. Nancy McClure By Bruce Eldredge Then again, how could we remain Executive Director Designer: unchanged when, through our Ms. Lindsay Lohrenz exhibitions, we’ve encountered Contributing Staff Photographers: the likes of artists John James Audubon, William Ranney, and Ms. Chris Gimmeson, Ms. Nancy McClure contemporary artist Charles Fritz? Or, photographers Gertrude Historic Photographs/Rights and Reproductions: Mr. Sean Campbell Kasëbier, Gus Foster, Robert Turner, and our own Charles Credits and Permissions: Belden and Jack Richard? We met Samuel Colt and the Colt Ms. -

Rocketry Basics Work Sheet 2013

ROCKETRY BASICS WORK SHEET 2013 School Name Launch Team Name Number Correct X 5 Points = Total Score After reviewing the educational information provided to your launch team, complete the following worksheet as a group. Each question is worth 5 points. Information needed to complete this worksheet is found in the booklet entitled “Rocketry Basics” and the “Motor Tutorial” on our website. There are also basic history questions that should be researched. 1 Which invention is basic to all rockets that reach outer space? A) Jean Froissart Launching rockets through tubes B) Hero of Alexandria of his invention of the Hero engine C) Schmidlap’s multi-stage vehicle for lifting fireworks to higher altitudes D) Mongol’s fire-arrows 2 The technique of ‘gyroscopic stabilization’, to improve rocket accuracy or power was developed by… A) William Gravesande B) Colonel William Congrave C) Wan-Her D) Robert Goddard E) Kai-Kang Goddard was interested in rockets reaching higher altitudes. Which of his developments became the forerunner of a whole new 3 era in rocket flight? A) Solid-propellant rocket B) Oxygen tanks C) Multi-Stage rocket D) Liquid propelled rockets using gasoline and liquid oxygen 4 What was the major scientific discovery made by the first US satellite? A) Discovery of Pluto B) First successful entry of a satellite into Earth orbit C) Discovery of the Van Allen Radiation Belts 5 Which Russian spacecraft was the first to fly past the moon? A) Lunar orbiter B) Explorer 1 C) Apollo 11 D) Lunar 1 The U. S. had 3 separate projects to gather information about the moon. -

2009 Spaceport News Summary

2009 Spaceport News Summary The 2009 Spaceport News used the above banner for the year. The “Spaceport News” portion picked up a bolder look, starting with the July 24, 2009, issue. Introduction The first issue of the Spaceport News was December 13, 1962. The 1963, 1964 and 1965 Spaceport News were issued weekly. The Spaceport News was issued every two weeks, starting July 7, 1966, until the last issue on February 24, 2014. Spaceport Magazine, a monthly issue, superseded the Spaceport News in April 2014, until the final issue, Jan./Feb. 2020. The two 1962 Spaceport News issues and the issues from 1996 until the final Spaceport Magazine issue, are available for viewing at this website. The Spaceport News issues from 1963 through 1995 are currently not available online. In this Summary, black font is original Spaceport News text, blue font is something I added or someone else/some other source provided, and purple font is a hot link. All links were working at the time I completed this Spaceport News Summary. The Spaceport News writer is acknowledged, if noted in the Spaceport News article. Page 1 From The January 9, 2009, Spaceport News On pages 4 and 5, “Scenes Around Kennedy Space Center”. “Space shuttle Endeavour is being lifted away from the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, or SCA, at Kennedy Space Center’s Shuttle Landing Facility on Dec. 13. The SCA gave the shuttle a piggyback ride from California, where Endeavour landed Nov. 30, ending the STS-126 mission.” On page 7, “747 took on jumbo task 35 years ago”, by Kay Grinter, Reference Librarian. -

Navy Search & Rescueteams Showtheir Stuff

1 F I The Navy Search & RescueTeams ShowTheir Stuff 1 A r P i =R 0 v) P .. 1win Harris sn 12 Leonaldo Ramos I 4 Andre Burke E L Fea~tures 16 Ex loring the Ocean 28 Missing a of 1pace Good Thing Find out bow Navy astronauts A phenomenon is sweep- are contributing to NASA ing the Navy; Sailors who and bringihg Naval traditions got out now want back 32 So Others into outer space. in. What's going on? May live When people are in distress, the Navy's Search and Rescue teams are at the ready. Learn the ins and outs of NAS /SARPatuxtent Team. River's 3 8 Being Martha Dunne She's the Navy Female Athlete of the Year, and when she's on her racing bicycle, her khaki uniform changes to sleek racing garb, her personality to cutthroat aggressiveness. EDITORIAL WEB DESIGN Editor DM1 Rhea Mackenzie Marie G. Johnston DM3 Michael Corte2 Managing Editor ART 8 DESIGN JOCS(AW) Dave Desilets Rabd &Bates Comunicafion wsign Assistant Editor Creative Director Debra Bates JOl Robert Benson Iwbnnbcsendaddnsa~to Art &Design Direaor /vIHanff, Havsl Media Wr, PubMlng C" Photo Editor 2713 Ml$cher Pd , S W Wngton D C 20373-5819 PH2(AW) Jim Watson Roger 0. Selvage, Jr. EdMomcm send submwonsandmnespondsnceto Editorial staff Graphic Designers Naval MlaCent81 RkllshlqGMm, ATtN Edltor 2713MkharRd SW.WashlngbM,DC 20373-5819 Dennis Everette Jane Farthing, Seth H. Serbaugh Td DI2884171 M @2)433.4171 Fax DSN 2884747 M (ZJ2) 433.4747 JOl Joseph Gunder I11 Digital Prepress Coordinator E-Mil a~~.m! JOl(SW/AW) Wayne Eternidca Lisa J. -

The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation

abraham lincoln presidential library AnnualFoundation Report July 1, 2014 ‒ June 30, 2015FY 15 The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation gratefully acknowledges the many individuals and organizations whose contributions helped to support the educational and cultural programming of the Abraham Lincoln Presi- dential Library and Museum during the fiscal year ending June 30, 2015. Their extraordinary generosity allows the Foundation to foster Lincoln scholar- ship through the acquisition and publication of documentary materials relating to Lincoln and his era; and to promote a greater appreciation of history through exhibits, conferences, publications, online services, and other activities designed to promote historical literacy. Annual Report Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation FY 15 FY15 FromAnnual the Chair-Wayne Report Whalen On April the 9th of 1865, while returning along the Potomac aboard the River Queen from visiting General Grant in The support ... that we Virginia, the President and Mrs. Lincoln along with their son Tad and several guests passed President Washington’s estate have received over the at Mount Vernon. Among those traveling with the Lincoln’s past fiscal year allows us was a Frenchman named Adolphe Pineton, Marquis de Chambrun, an attorney who had married into the Lafayette to continue to advance family and secured a minor diplomatic post to observe the the legacy of our nation’s progress of the Civil War. Upon seeing the grand home of the father of the nation, Chambrun exclaimed “Mount Vernon, greatest President—so Wayne Whalen with its memories of Washington, and Springfield, with those that future generations of your own home—revolutionary and civil war—will be equally honored in America.” Upon hearing this Mr. -

Spaceflight Now STS-102/ISS-5A.1 Quick-Look Data

STS-102/ISS-5A.1 Quick-Look Data Spaceflight Now spaceflightnow.com Position STS-102 ISS-5A.1 Family DOB STS-102 Hardware and Flight Data Commander Navy. Capt. James Wetherbee, 48 Married/2 11/27/52 STS Mission STS-102/ISS-5A.1 STS-32, 52, 63, 86 Orbiter Discovery/OV-103 (29) Pilot/IV Air Force Lt. Col. James Kelly, 36 Married/4 05/14/64 Payload Crew ferry; MPLM Rookie Launch 06:42:09 AM 03.08.01 MS1/EV3 Andrew Thomas, Ph.D., 49 Single/0 12/18/51 Pad/MLP/FR 39B/MLP-3/FR 2-1 STS-77, 89/Mir7/91 Prime TAL Zaragoza, Spain MS2/FE/EV4 Paul Richards, 36 Married/3 05/20/64 Landing 02:02:00 AM 03.20.01 Rookie Landing Site KSC, Runway 15/33 STS UP ISS Expedition 2 (shuttle up/shuttle down) Duration 11/19:20 ISS-2 CDR Yury Usachev, 43 Married/1 10/09/57 Soyuz TM-18, TM-23, STS-101 Discovery 217/06:17:38 ISS-2/EV1 Mr. James Voss, 52 Married/1 03/03/49 STS Program 894/04:19:22 STS-44, 53, 69, 101 ISS-2/EV2 Air Force Col. Susan Helms, 43 Single/0 02/26/58 MECO Ha/Hp 137 X 36 sm STS-54, 64, 78, 101 OMS Ha/Hp 143 X 121 sm STS DOWN ISS Expedition 1 (Soyuz up/shuttle down) ISS Ha/Hp 235 X 229 (varies) ISS-1 CDR William Shepherd, 51 Married/0 07/26/49 Period 92.3 minutes STS-27, 41, 52, TM-31/ISS-1 Inclination 51.6 degrees ISS-1 Yuri Gidzenko, 38 Married/2 03/26/62 Velocity 17,169 mph Soyuz TM-22, TM-31/ISS-1 EOM Miles 4.86 million ISS-1 Sergei Krikalev, 42 Married/1 08/27/58 EOM Orbits 184 (land on 185) Soyuz TM-7, TM-12, STS-60, STS-88, TM-31/ISS-1 SSMEs (2A) 2056, 2053, 2045 STS-102 Cargo/Element Weights STS-102 Patch ET/SRB 107/BI106-RSRM 78 Software -

Astronaut Fact Book

Information Summaries National Aeronautics and Space Administration JULY 2003 NP-2003-07-008JSC Astronaut Fact Book “Once you get to Earth orbit, you're halfway to anywhere in the solar system." -- Robert Heinlein JULY 2003 PREFACE The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) selected the first group of astronauts in 1959. From 500 candidates having the required jet aircraft flight experience and engineering training as well as height below 5 feet 11 inches, 7 military men became the Nation's first astronauts. The second and third groups chosen included civilians who had extensive flying experience. By 1964, requirements had changed, and emphasis was placed on academic qualifications; in 1965, 6 scientist astronauts were selected from a group of 400 applicants who had a Doctorate or equivalent experience in the natural sciences, medicine, or engineering. The group named in 1978 was the first of space shuttle flight crews and since then, 8 additional groups have been selected with a mix of pilots and mission specialists. There are currently 108 astronauts and 36 management astronauts in the program; 133 astronauts have retired or resigned; and 35 are deceased. Though most of the information in this document pertains only to U.S. Astronauts, several sections are included to provide information about the international astronauts and Russian trained Cosmonauts who are currently partners with the U.S. Space Program participating in the International Space Station endeavor. The non-U.S. information presented here was gathered from the biographies provided by the various space agencies with which these individuals are affiliated. Payload specialists are career scientists or engineers selected by their employer or country for their expertise in conducting a specific experiment or commercial venture on a space shuttle mission. -

![Shepherd, Sampson Family - 1708.Txt[12/12/2018 10:31:41 AM] Iv](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1224/shepherd-sampson-family-1708-txt-12-12-2018-10-31-41-am-iv-4771224.webp)

Shepherd, Sampson Family - 1708.Txt[12/12/2018 10:31:41 AM] Iv

Descendants of Sampson Shepherd Generation No. 1 1. SAMPSON1 SHEPHERD was born 1708 in Currituck County, NC, and died in North Carolina. He married ELIZABETH HIGHSMITH. She was born 1749. Children of SAMPSON SHEPHERD and ELIZABETH HIGHSMITH are: i. JAMES PENDLETON2 SHEPHERD, b. May 18, 1767, Halifax Countu, NC. ii. SAMPSON SHEPHERD, b. 1770, North Carolina. iii. WILLIAM SHEPHERD, b. 1775, Halifax Countu, NC. 2. iv. URIAH OLD JACK SHEPHERD, b. 1780, North Carolina. Generation No. 2 2. URIAH OLD JACK2 SHEPHERD (SAMPSON1) was born 1780 in North Carolina. He married ELIZABETH SMITH, daughter of JAYLOR SMITH and NANCY MULKEY. She was born Bet. 1780 - 1790 in Virginia. Children of URIAH SHEPHERD and ELIZABETH SMITH are: 3. i. JAMES JIM3 SHEPHERD, b. 1805, Virginia; d. 1852. 4. ii. WILLIAM SHEPHERD, b. 1807, Jackson County, Alabama; d. January 1862, Bidville, Crawford County, Arkansas. 5. iii. MARY POLLY SHEPHERD, b. January 08, 1810, Jackson County, Alabama; d. 1890, Wedington Community, Washington County, Arkansas. 6. iv. JOHN JACK SHEPHERD, b. 1814, Jackson County, Alabama; d. 1893, Crawford County, AR. v. THOMAS TOM SHEPHERD, b. 1820, Virginia; m. (1) MARY A. HANNA, 1837, Washington County, AR; b. 1820, Floyd County, Kentucky; m. (2) EMALINE WADE, 1846, Lawrence County, Union Twp, Arkansas; b. 1809, Alabama. Generation No. 3 3. JAMES JIM3 SHEPHERD (URIAH OLD JACK2, SAMPSON1) was born 1805 in Virginia, and died 1852. He married HANNAH PETERS, daughter of HENRY PETERS. She was born April 11, 1808 in Sevier County, Tennessee, and died January 30, 1872 in Oregon. Children of JAMES SHEPHERD and HANNAH PETERS are: i. -

Lyndon Larouche Political Action Committee LAROUCHE PAC Larouchepac.Com Facebook.Com/Larouchepac @Larouchepac

Lyndon LaRouche Political Action Committee LAROUCHE PAC larouchepac.com facebook.com/larouchepac @larouchepac Restoring the Soul of America THE EXONERATION OF LYNDON LAROUCHE Table of Contents Helga Zepp-LaRouche: For the Exoneration of 2 the Most Beautiful Soul in American History Obituary: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. (1922–2019) 9 Selected Condolences and Tributes 16 Background: The Fraudulent 25 Prosecution of LaRouche Letter from Ramsey Clark to Janet Reno 27 Petition: Exonerate LaRouche! 30 Prominent Petition Signers 32 Prominent Signers of 1990s Statement in 36 Support of Lyndon LaRouche’s Exoneration LLPPA-2019-1-0-0-STD | COPYRIGHT © MAY 2019 LYNDON LAROUCHE PAC, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Cover photo credits: EIRNS/Stuart Lewis and Philip Ulanowsky INTRODUCTION For the Exoneration of the Most Beautiful Soul in American History by Helga Zepp-LaRouche There is no one in the history of the United States to my knowledge, for whom there is a greater discrep- ancy between the image crafted by the neo-liberal establishment and the so-called mainstream media, through decades of slanders and co- vert operations of all kinds, and the actual reality of the person himself, than Lyndon LaRouche. And that is saying a lot in the wake of the more than two-year witch hunt against President Trump. The reason why the complete exoneration of Lyn- don LaRouche is synonymous with the fate of the United States, lies both in the threat which his oppo- nents pose to the very existence of the U.S.A. as a republic, and thus for the entire world, it system, the International Development Bank, which and also in the implications of his ideas for America’s fu- he elaborated over the years into a New Bretton Woods ture survival.