Looking Backward, Looking Forward: Forty Years of Human Spaceflight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPEAKERS TRANSPORTATION CONFERENCE FAA COMMERCIAL SPACE 15TH ANNUAL John R

15TH ANNUAL FAA COMMERCIAL SPACE TRANSPORTATION CONFERENCE SPEAKERS COMMERCIAL SPACE TRANSPORTATION http://www.faa.gov/go/ast 15-16 FEBRUARY 2012 HQ-12-0163.INDD John R. Allen Christine Anderson Dr. John R. Allen serves as the Program Executive for Crew Health Christine Anderson is the Executive Director of the New Mexico and Safety at NASA Headquarters, Washington DC, where he Spaceport Authority. She is responsible for the development oversees the space medicine activities conducted at the Johnson and operation of the first purpose-built commercial spaceport-- Space Center, Houston, Texas. Dr. Allen received a B.A. in Speech Spaceport America. She is a recently retired Air Force civilian Communication from the University of Maryland (1975), a M.A. with 30 years service. She was a member of the Senior Executive in Audiology/Speech Pathology from The Catholic University Service, the civilian equivalent of the military rank of General of America (1977), and a Ph.D. in Audiology and Bioacoustics officer. Anderson was the founding Director of the Space from Baylor College of Medicine (1996). Upon completion of Vehicles Directorate at the Air Force Research Laboratory, Kirtland his Master’s degree, he worked for the Easter Seals Treatment Air Force Base, New Mexico. She also served as the Director Center in Rockville, Maryland as an audiologist and speech- of the Space Technology Directorate at the Air Force Phillips language pathologist and received certification in both areas. Laboratory at Kirtland, and as the Director of the Military Satellite He joined the US Air Force in 1980, serving as Chief, Audiology Communications Joint Program Office at the Air Force Space at Andrews AFB, Maryland, and at the Wiesbaden Medical and Missile Systems Center in Los Angeles where she directed Center, Germany, and as Chief, Otolaryngology Services at the the development, acquisition and execution of a $50 billion Aeromedical Consultation Service, Brooks AFB, Texas, where portfolio. -

OCTOBER 2016 Welcome to October Sky! We Can’T Imagine a More Perfect Show to Give Our 2016–2017 Season a Great Launch (If You’Ll Pardon the Pun)

OCTOBER 2016 Welcome to October Sky! We can’t imagine a more perfect show to give our 2016–2017 Season a great launch (if you’ll pardon the pun). New musicals are, of course, one of The Old Globe’s specialties, and the upcoming season is filled with exactly the kind of work the Globe does best. In this very theatre, you’ll have a chance to see a revival of Steve Martin’s hilarious Picasso at the Lapin Agile; the exciting backstage drama Red Velvet; and the imaginative, fable- like musical The Old Man and The Old Moon. And of course, we’re bringing back The Grinch for its 19th year! Across the plaza in the Sheryl and Harvey White Theatre, we hope you’ll join us for work by some of the most exciting voices in the American theatre today: award-winning actor/ songwriter Benjamin Scheuer (The Lion), Globe newcomer Nick Gandiello (The Blameless), the powerful and trenchant Dominique Morisseau (Skeleton Crew), and the ingenious Fiasco Theater, with their own particular spin on Molière’s classic The Imaginary Invalid. It’s a season we’re extremely proud and excited to share with all of you. DOUGLAS GATES Managing Director Michael G. Murphy and Erna Finci Viterbi Artistic Director Barry Edelstein. We’re also proud to welcome the outstanding creative team that has made October Sky a reality. Director/choreographer Rachel Rockwell is an artist whose work we’ve long admired, whose skill in staging is matched by her deft touch with actors. She’s truly a perfect fit for this heartwarming and triumphant show. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Baikonur-International Space Station : International Approach to Lunar Exploration

ICEUM4, 10-15 July 2000, ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands Baikonur-International Space Station : International Approach to Lunar Exploration Gulnara Omarova, National Aerospace Agency; Chinghis Omarov, ISU Summer Session '98 alumni On 20th November 1998 our aircraft made soft landing at the Baikonur airport. I was among onboard passengers - officials from Kazakhstan Space, press and diplomats. We all were invited to attend the launch of the International Space Station (ISS) first component (the Russian-made Zarya or Functional Cargo Module FGB) by Proton launch-vehicle at the Baikonur spaceport. Two hours before ISS first module launch we joined the official delegations from NASA, Russian Space Agency (RSA), ESA, Canadian Space Agency (CSA) and NASDA to see the modified facilities of both "Energiya" Corp. and Khrunichev's Proton assembly-and- test building. Mr. Yuri Koptev, Chief of RSA and Mr. Dan Goldin, NASA Administrator actively were drinking russian tea and talking about crucial issues of the International Space Station and the future of Space Exploration. In fact, Cold War is over and the world's top space powers accomplishments are stunning: • The first human flight in space in 1961; • Human space flight initiatives to ascertain if and how long a human could survive in space; • Project Gemini (flights during 1965-1966) to practice space operations, especially rendezvous and docking of spacecraft and extravehicular activity; • Project Apollo (flights during 1968-1972) to explore the Moon; • Space Shuttle's flights (1981 - present); • Satellite programs; • A permanently occupied space station "Mir" (during 1976-1999); • A permanently occupied International Space Station presently underway. We and a few people approached them to learn much more particulars of their talking and to ask them most interesting questions. -

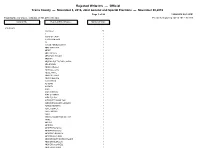

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

TABLE of CONTENTS LINDA HALL LIBRARY

TABLE of CONTENTS Front Cover .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Leadership Marilyn B. Hebenstreit ................................................................................................................................. 3 Lisa Browar ................................................................................................................................................. 4 LINDA HALL LIBRARY Programs: Exhibitions and Events Annual Report 2008 Lectures & Other Events ............................................................................................................................... 5 ICE: A Victorian Romance ............................................................................................................................ 7 Locomotion: Railroads in the Early Age of Steam ............................................................................................. 9 ASM Materials Camp ..................................................................................................................................... 11 2008 Events: Complete Listing ..................................................................................................................... 13 The Collections Recent Acquisitions .................................................................................................................................... -

Frontier in Space

FRONTIER IN SPACE SPACE THE final frontier, human condition. What is good says: “It’s about two different kinds as someone once said. about us? What is bad about us? of humanity coming into contact But… is it… really? Executive producer Nicholas with each other: a culture-clash of Humanity may well travel away Briggs, who devised this series, is no people from hundreds of years apart from Earth in the future, but surely stranger to developing adventures coming face to face. It’s also a love that’s just the beginning rather without a certain Time Lord, story, a story of a struggle for power than the end? having previously created the and a bit of a murder mystery too. This concept is at the heart of unique and critically-acclaimed It’s a futuristic adventure with all The Human Frontier, the latest Dalek Empire series, which the science fiction trappings, but it’s Big Finish Original, an epic science featured the mutants from Skaro. a very human drama at its heart. fiction series about exploration Vortex asked Nick to sum up what “I’ve always been fascinated by – not just of space but of the The Human Frontier is about. He how our society, our assumptions VORTEX | PAGE 10 BIG FINISH ORIGINALS THE HUMAN FRONTIER discovering a ‘colony’ of people from 300 years ago. Imagine how we’d differ from them in so many ways.” Vortex suggests that there is an element of ‘risk’, for want of a word, in creating a series from scratch, unlike writing for the Doctor, Dalek Empire, or even reimagining The Prisoner or Space: 1999. -

Colonel Gordon Cooper, US Air Force Leroy Gordon

Colonel Gordon Cooper, U.S. Air Force Leroy Gordon "Gordo" Cooper Jr. was an American aerospace engineer, U.S. Air Force pilot, test pilot, and one of the seven original astronauts in Project Mercury, the first manned space program of the U.S. Cooper piloted the longest and final Mercury spaceflight in 1963. He was the first American to sleep in space during that 34-hour mission and was the last American to be launched alone to conduct an entirely solo orbital mission. In 1965, Cooper flew as Command Pilot of Gemini 5. Early life and education: Cooper was born on 6 March 1927 in Shawnee, OK to Leroy Gordon Cooper Sr. (Colonel, USAF, Ret.) and Hattie Lee Cooper. He was active in the Boy Scouts where he achieved its second highest rank, Life Scout. Cooper attended Jefferson Elementary School and Shawnee High School and was involved in football and track. He moved to Murray, KY about two months before graduating with his class in 1945 when his father, Leroy Cooper Sr., a World War I veteran, was called back into service. He graduated from Murray High School in 1945. Cooper married his first wife Trudy B. Olson (1927– 1994) in 1947. She was a Seattle native and flight instructor where he was training. Together, they had two daughters: Camala and Janita Lee. The couple divorced in 1971. Cooper married Suzan Taylor in 1972. Together, they had two daughters: Elizabeth and Colleen. The couple remained married until his death in 2004. After he learned that the Army and Navy flying schools were not taking any candidates the year he graduated from high school, he decided to enlist in the Marine Corps. -

L-8: Enabling Human Spaceflight Exploration Systems & Technology

Johnson Space Center Engineering Directorate L-8: Enabling Human Spaceflight Exploration Systems & Technology Development Public Release Notice This document has been reviewed for technical accuracy, business/management sensitivity, and export control compliance. It is Montgomery Goforth suitable for public release without restrictions per NF1676 #37965. November 2016 www.nasa.gov 1 NASA’s Journey to Mars Engineering Priorities 1. Enhance ISS: Enhanced missions and systems reliability per ISS customer needs 2. Accelerate Orion: Safe, successful, affordable, and ahead of schedule 3. Enable commercial crew success 4. Human Spaceflight (HSF) exploration systems development • Technology required to enable exploration beyond LEO • System and subsystem development for beyond LEO HSF exploration JSC Engineering’s Internal Goal for Exploration • Priorities are nice, but they are not enough. • We needed a meaningful goal. • We needed a deadline. • Our Goal: Get within 8 years of launching humans to Mars (L-8) by 2025 • Develop and mature the technologies and systems needed • Develop and mature the personnel needed L-8 Characterizing L-8 JSC Engineering: HSF Exploration Systems Development • L-8 Is Not: • A program to go to Mars • Another Technology Road-Mapping effort • L-8 Is: • A way to translate Agency Technology Roadmaps and Architectures/Scenarios into a meaningful path for JSC Engineering to follow. • A way of focusing Engineering’s efforts and L-8 identifying our dependencies • A way to ensure Engineering personnel are ready to step up -

The Esa Exploration Programme – Exomars and Beyond

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVI (2005) 2408.pdf THE ESA EXPLORATION PROGRAMME – EXOMARS AND BEYOND. G. Kminek1 and the Exploration Team, 1European Space Agency, D/HME, Keplerlaan 1, 2200 AG Noordwijk, The Netherlands, [email protected]. Management and Organization: The countries Technology Development for Exploration: Two participating in the European Exploration Programme categories for exploration technology developments Aurora have recently confirmed and increased their have been identified: contribution. The ESA Council has later approved the Generic Exploration Technology: They have a Agency’s budgets for 2005, including the budget for long-term strategic value, both for robotic and human Aurora. These developments enable major industrial exploration missions. Planetary protection, habitable activities to continue in line with original plans. These systems, risk assessment for human missions to planets, include work on the ExoMars mission and the Mars grey and black water recycling as well as psychological Sample Return mission, in-orbit assembly, rendezvous support for the Concordia Antarctic Station, Facility and docking, habitation and life support systems plus a for Integrated Planetary Exploration Simulations are broad range of technology development work. examples of selected generic exploration technologies. The Aurora Exploration Programme has been inte- Mission Specific Technologies: Specifically devel- grated into the Human Spaceflight and Microgravity oped for the programme’s missions, and will eventually Directorate , which now forms the Human Spaceflight, be implemented after reaching a minimum technology Microgravity, and Exploration Directorate of ESA. readiness level. EVD, sealing and sealing monitoring Early Robotic Missions: Robotic mission have technology, containment technology, specific instru- been identified as necessary prerequisite before send- ment developments, sample handling and distribution ing human to Mars. -

Prologemena to an Future Rhetoric of Shadows, Shades and Silhouettes

Utah State University From the SelectedWorks of Gene Washington January 2014 PROLOGEMENA TO AN FUTURE RHETORIC OF SHADOWS, SHADES AND SILHOUETTES Contact Start Your Own Notify Me Author SelectedWorks of New Work Available at: http://works.bepress.com/gene_washington/157 PROLEGOMENA TO ANY FUTURE RHETORIC OF SHADOWS, SHADES AND SILHOUETTES Man that is born of a woman hath but a short time to live, and is full of misery. He cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower; he fleeth as it were a shadow , and never continueth in one stay. In the mid of life we are in death (1662 Anglican Church "Burial of the Dead"). *** But mark, madam, we live amongst riddles and mysteries—the most obvious things, which come in our way, have dark sides, which the quickest sight cannot penetrate into; and even the clearest and most exalted understandings amongst us find ourselves puzzled and at a loss in almost every cranny of nature's works. Laurence Sterne (1713-68) Stepping out of the shadows…I…. Rhetoric, as a subject of investigation, is perhaps older than the invention of writing. One piece of evidence for this is its root in the Indo-European word, aera , "to say (something) with a specific intention" (Greek ρ in direct descent to the modern 1 age; please see Buck, entry under "speak, say,"). Another kind of evidence is the abundance of treatises on rhetoric, Aristotle, Cicero, Quintilian, Burke, Booth and Ong to mention some of the most prominent. Despite their differences in method, all these authors would perhaps agree that the key ingredient of rhetoric is author/speaker intentionality— the power of minds to be about, to represent, or to stand for, things, properties and states of affairs plus non-existent things. -

Orbital Debris: a Chronology

NASA/TP-1999-208856 January 1999 Orbital Debris: A Chronology David S. F. Portree Houston, Texas Joseph P. Loftus, Jr Lwldon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas David S. F. Portree is a freelance writer working in Houston_ Texas Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................ iv Preface ........................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... vii Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................ ix The Chronology ............................................................................................................. 1 1961 ......................................................................................................................... 4 1962 ......................................................................................................................... 5 963 ......................................................................................................................... 5 964 ......................................................................................................................... 6 965 ......................................................................................................................... 6 966 ........................................................................................................................