Continuity and Conundrums in Lincolnshire Minor Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

<Election Title>

North Lincolnshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Barrow upon Humber Parish NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. The following persons have been and stand validly nominated: SURNAME OTHER NAMES HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION NAMES OF THE PROPOSER (P), (if any) SECONDER (S) AND THE PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE NOMINATION PAPER Morris Valerie 3 John Harrison Close, Mary Thornton(P), Graham W Barrow-upon-Humber, Thornton(S) North Lincolnshire, DN19 7BE Sewell David Peter Sunnydene, St. Chad, Philip Glew(P), Clare Glew(S) Barrow-upon-Humber, North Lincolnshire, DN19 7AU Sewell Vivienne Denise Sunnydene, St. Chad, Annette Smith(P), Helen Susan Barrow-upon-Humber, Anglum(S) North Lincolnshire, DN19 7AU Wilkinson Paul Davy Ivydene, Marsh Lane, Labour Party Catherine Hindson(P), Peter Swann(S) Barrow Haven, Barrow upon Humber, DN19 7EP 2. A POLL for the above election will be held on Thursday, 26th August 2021 between the hours of 7:00am and 10:00pm 3. The number to be elected is THREE The situation of the Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote at each station are set out below: PD Polling Station and Address Persons entitled to vote at that station FER1 1 / FER1 Barrow upon Humber Village Hall, High Street, Barrow-On-Humber, North Lincolnshire, 1 to 2404 DN19 7AA FER2 2 / FER2 Function Room, Haven Inn, Ferry Road, Barrow Haven 3 to 119 Dated: Wednesday, 18th August 2021 Denise Hyde Returning Officer North Lincolnshire Council Church Square House 30-40 High Street Scunthorpe North Lincolnshire DN15 6NL Printed and Published by Denise Hyde Returning Officer North Lincolnshire Council Church Square House 30-40 High Street Scunthorpe North Lincolnshire DN15 6NL . -

Hornsea One and Two Offshore Wind Farms About Ørsted | the Area | Hornsea One | Hornsea Two | Community | Contact Us

March 2019 Community Newsletter Hornsea One and Two Offshore Wind Farms About Ørsted | The area | Hornsea One | Hornsea Two | Community | Contact us Welcome to the latest community newsletter for Hornsea One and Two Just over a year ago we began offshore construction on Hornsea One, and now, 120 km off the coast, the first of 174 turbines have been installed and are generating clean, renewable electricity. Following a series of local information events held along our onshore cable route, the onshore construction phase for Hornsea Two is now underway. We will continue to work to the highest standards already demonstrated by the teams involved, and together deliver the largest renewable energy projects in the UK. Kingston Upon Hull Duncan Clark Programme Director, Hornsea One and Two We are a renewable energy company with the vision to create a world About that runs entirely on green energy. Climate change is one of the biggest challenges for life on earth; we need to transform the way we power the Ørsted world. We have invested significantly in the UK, where we now develop, construct and operate offshore wind farms and innovative biotechnology which generates energy from household waste without incineration. Over the last decade, we have undergone a truly green transformation, halving our CO2 emissions and focusing our activities on renewable sources of energy. We want to revolutionise the way we provide power to people by developing market leading green energy solutions that benefit the planet and our customers alike. March 2019 | 2 About -

Tree Preservation Order Register (As of 13/03/2019)

North East Lincolnshire - Tree Preservation Order Register (as of 13/03/2019) TPO Ref Description TPO Status Served Confirmed Revoked NEL252 11 High Street Laceby Confirmed 19/12/2017 05/06/2018 NEL251 Land at 18, Humberston Avenue, Humberston Lapsed 06/10/2017 NEL245 Land at The Becklands, Waltham Road, Barnoldby Le Beck Served 08/03/2019 NEL244 104/106, Caistor Road, Laceby Confirmed 12/02/2018 06/08/2018 NEL243 Land at Street Record, Carnoustie, Waltham Confirmed 24/02/2016 27/05/2016 NEL242 Land at 20, Barnoldby Road, Waltham Confirmed 24/02/2016 27/05/2016 NEL241 Land at Peartree Farm, Barnoldby Road, Waltham Confirmed 24/02/2016 27/05/2016 NEL240 Land at 102, Laceby Road, Grimsby Confirmed 01/02/2016 27/05/2016 NEL239 Land at 20, Scartho Road, Grimsby Confirmed 06/11/2014 10/03/2015 NEL238 Land at The Cedars, Eastern Inway, Grimsby Confirmed 21/11/2014 10/03/2015 NEL237 Land at 79, Weelsby Road, Grimsby Revoked 23/07/2014 10/03/2015 NEL236 Land at 67, Welholme Avenue, Grimsby Confirmed 21/03/2014 21/08/2014 NEL235 Land at 29-31, Chantry Lane, Grimsby Confirmed 10/02/2014 21/08/2014 NEL234 Land at Street Record,Main Road, Aylesby Confirmed 21/06/2013 09/01/2014 NEL233 Land at 2,Southern Walk, Grimsby Confirmed 12/08/2013 09/01/2014 NEL232 34/36 Humberston Avenue Confirmed 11/06/2013 28/01/2014 NEL231 Land at Gedney Close, Grimsby Confirmed 06/03/2013 19/11/2013 NEL230 Land at Hunsley Crescent, Grimsby Confirmed 04/03/2013 19/11/2013 NEL229 Land at 75,Humberston Avenue, Humberston Confirmed 16/01/2013 12/02/2013 NEL228 Land at St. -

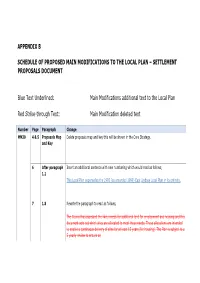

SETTLEMENT PROPOSALS DOCUMENT Blue Text Underlined

APPENDIX B SCHEDULE OF PROPOSED MAIN MODIFICATIONS TO THE LOCAL PLAN – SETTLEMENT PROPOSALS DOCUMENT Blue Text Underlined: Main Modifications additional text to the Local Plan Red Strike-through Text: Main Modification deleted text Number Page Paragraph Change MM30 4 & 5 Proposals Map Delete proposals map and key this will be shown in the Core Strategy. and Key 6 After paragraph Insert an additional sentence with new numbering which would read as follows; 1.1 This Local Plan supersedes the 1995 (as amended 1999) East Lindsey Local Plan in its entirety. 7 1.8 Rewrite the paragraph to read as follows; The Council has assessed the likely needs for additional land for employment and housing and this document sets out which sites are allocated to meet those needs. These allocations are intended to enable a continuous delivery of sites for at least 15 years (for housing). The Plan is subject to a 5 yearly review to ensure an adequate supply of housing and to assess the impact of a policy of housing restraint on the coast. These allocations are intended to enable a continuous delivery of sites until the end of the plan period. The Plan is subject to a review by April 2022 to ensure an adequate supply of housing and to assess the impact of the policy of restraint on the Coast”. 8 1.9 Amend the paragraph so that it reflects the figures for housing in the Core Strategy; The Core Strategy sets out that there is a requirement to provide sites for 7819 homes from 2017 to 2031. -

Excavations at Aylesby, South Humberside, 1994

EXCAVATIONS AT AYLESBY, SOUTH HUMBERSIDE, 1994 Ken Steedman and Martin Foreman Re-formatted 2014 by North East Lincolnshire Council Archaeological Services This digital report has been produced from a hard/printed copy of the journal Lincolnshire History and Archaeology (Volume 30) using text recognition software, and therefore may contain incorrect words or spelling errors not present in the original. The document remains copyright of the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology and the Humberside Archaeology Unit and their successors. This digital version is also copyright of North East Lincolnshire Council and has been provided for private research and education use only and is not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. Front Cover: Aylesby as it may have looked in the medieval period, reconstructed from aerial photographs and excavated evidence (watercolour by John Marshall). Image reproduced courtesy of the Society for Lincolnshire History & Archaeology © 1994 CONTENTS EXCAVATIONS AT AYLESBY, SOUTH HUMBERSIDE, 1994 ........................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 SELECT DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE FOR THE PARISH OF AYLESBY ................................. 3 PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL WORK ........................................................................................ 8 THE EXCAVATIONS ...................................................................................................................... -

7.6.5.07 Local Receptors for Landfall and Cable Route

Environmental Statement Volume 6 – Onshore Annex 6.5.7 Representative Visual Receptors for Landfall and Cable Route PINS Document Reference: 7.6.5.7 APFP Regulation 5(2)(a) January 2015 SMart Wind Limited Copyright © 2015 Hornsea Offshore Wind Farm Project Two –Environmental Statement All pre-existing rights reserved. Volume 6 – Onshore Annex 6.5.7 - Local Receptors for Landfall and Cable Route Liability This report has been prepared by RPS, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of their contracts with SMart Wind Ltd or their subcontractor to RPS placed under RPS’ contract with SMart Wind Ltd as the case may be. Document release and authorisation record PINS document reference 7.6.5.7 Report Number UK06-050700-REP-0039 Date January 2015 Client Name SMart Wind Limited SMart Wind Limited 11th Floor 140 London Wall London EC2Y 5DN Tel 0207 7765500 Email [email protected] i Table of Contents 1 Public Rights of Way (as visual receptors) within 1 km of the cable route and landfall ........ 1 Table of Tables Table 1.1 Public Rights of Way (as visual receptors) within 1 km of the Landfall, Cable Route and Onshore HVDC Converter/HVAC Substation ..................................................... 1 Table of Figures Figure 6.5.7 Local Receptors ..................................................................................................... 6 ii 1 PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY (AS VISUAL RECEPTORS) WITHIN 1 KM OF THE CABLE ROUTE, LANDFALL AND ONSHORE HVDC CONVERTER/HVAC SUBSTATION Table 1.1 Public Rights of Way (as visual -

Lincolnshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2003 Desk-based Assessments East Midlands LINCOLNSHIRE Boston 1/56 (B.32.O023) TF 30444362 PE21 7TG GILBERT DIVE, WYBERTON FEN Commercial Development at Gilbert Drive, Wyberton Fen, Boston, Lincolnshire Cope-Faulkner, P Sleaford : Archaeological Project Services, 2003, 28pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Project Services An archaeological assessment was carried out on the proposed development site. The assessment identified archaeology within the assessment area from the prehistoric to modern periods. No archaeology was identified within the proposed development site, apart from impacting alluvial deposits, the development impact was seen as limited. [Au(abr)] 1/57 (B.32.O016) TF 32754342 PE21 8AG LAND AT 138-142 HIGH STREET, BOSTON Land at 138-142 High Street, Boston, Lincolnshire Cope-Faulkner, P Sleaford : Archaeological Project Services, 2003, 26pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Project Services An archaeological assessment was carried out on the site. This identified that the development area was within the bounds of the medieval town and that medieval archaeology had been revealed elsewhere on the High Street. Evidence for occupation of the High Street for the post-medieval period had been found and a cartographic source revealed that part of the site contained an Inn in 1784. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: MD, PM East Lindsey 1/58 (B.32.O025) TF 13407941 PE28 3QR HOLTON CUM BECKERING Holton cum Beckering, Welton Gathering Centre, Gas Pipeline Tann, G Lincoln : Lindsey Archaeological Services, 2003, 32pp, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: Lindsey Archaeological Services An archaeological assessment was carried out on the proposed gas pipeline. -

Lincolnshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2002 Desk-Based Assessments East Midlands Region LINCOLNSHIRE Boston 1/26 (B.32.H002) TF 32674432 LAND BETWEEN COLLEY STREET AND ARCHER LANE Land Between Colley Street and Archer Lane, Boston Albone, J Sleaford : Archaeological Project Services, 2002, 33pp, colour pls, figs, tabs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Project Services An archaeological assessment was carried out on the proposed development site. The assessment identified that although the site has no known archaeology, medieval archaeology has been identified in the vicinity and the site was located within the bounds of the medieval town. Further work was recommended. [Au(abr)] SMR primary record number: 2844 East Lindsey 1/27 (B.32.H013) TF 32257263 CLAPGATE FARM, GREETHAM WITH SOMERSBY Clapgate Farm, Greetham with Somersby, Lincs Tann, G Lincoln : Lindsey Archaeological Services, 2002, 12pp, figs, tabs Work undertaken by: Lindsey Archaeological Services An archaeological assessment was carried out on the proposed reservoir site. No archaeological finds or features have been identified or recovered from the site, although prehistoric and medieval finds have been recovered from nearby. [Au(abr)] 1/28 (B.32.H011) TF 37776368 THE FORMER EAST KEAL GARDEN CENTRE The Former East Keal Garden Centre, East Keal, Spilsby, Lincolnshire Trimble, R Lincoln : City of Lincoln Archaeology Service, 2002, 24pp, colour pls, figs, tabs Work undertaken by: City of Lincoln Archaeology Unit An archaeological assessment was carried out on the proposed development site. The assessment identified prehistoric to post-medieval archaeology within the immediate vicinity of the site. The site was identified as having potential for early medieval to medieval archaeology and a 1757 map shows the site containing tenant farm buildings. -

110-Manby-Road-Immingham.Pdf

Former ATS Euromaster Premises, 110 Manby Road, Immingham, DN40 2LQ FOR SALE Detached industrial premises in an established location Accommodation extending to c.498.6 sq m (5,367 sq ft) overall plus mezzanines Site area of c.0.56 acres (0.23 hectares) Rare freehold opportunity Good road links and accessibility to the Immingham Dock and Humber Refinery Guide Price £300,000 Former ATS Euromaster Premises, LOCATION/DESCRIPTION Immingham is a town, positioned on the south bank of the Humber Estuary within North East Lincolnshire, with a resident population 110 Manby Road, Immingham, DN40 2LQ of approximately 11,500 (Source: 2011 Census). The town is situated approximately 3 miles north-west of Stallingborough, 6 miles north-west of Grimsby and 11 miles south-east of Barrow upon Humber. The property is located on the southern side of Manby Road which forms one of the main arterial routes providing access between the A160/A180 and Immingham Dock. The property comprises detached industrial premises, previously occupied by ATS Euromaster, with ancillary loading, storage or parking areas to the front and rear. The workshop provides the potential for clear-span accommodation, but currently incorporates a FOR SALE customer reception, staff ancillary facilities and two mezzanines, one of which houses a small office. The building is accessible via four roller shutters with c.5.0m height clearance, provides c.7.5m clearance to the apex and incorporates a storage area to the rear, albeit at a lower height. To the rear, the property benefits from a compound-style yard of c.0.3 acres, surfaced using compacted hardcore, which could have future development potential subject to obtaining the necessary planning consents. -

NCA Profile 42 Lincolnshire Coast and Marshes

National Character 42. Lincolnshire Coast and Marshes Area profile: Supporting documents www.gov.uk/natural-england 1 National Character 42. Lincolnshire Coast and Marshes Area profile: Supporting documents Introduction National Character Areas map As part of Natural England’s responsibilities as set out in the Natural Environment White Paper,1 Biodiversity 20202 and the European Landscape Convention,3 we are revising profiles for England’s 159 National Character Areas North (NCAs). These are areas that share similar landscape characteristics, and which East follow natural lines in the landscape rather than administrative boundaries, making them a good decision-making framework for the natural environment. Yorkshire & The North Humber NCA profiles are guidance documents which can help communities to inform West their decision-making about the places that they live in and care for. The information they contain will support the planning of conservation initiatives at a East landscape scale, inform the delivery of Nature Improvement Areas and encourage Midlands broader partnership working through Local Nature Partnerships. The profiles will West also help to inform choices about how land is managed and can change. Midlands East of Each profile includes a description of the natural and cultural features England that shape our landscapes, how the landscape has changed over time, the current key drivers for ongoing change, and a broad analysis of each London area’s characteristics and ecosystem services. Statements of Environmental South East Opportunity (SEOs) are suggested, which draw on this integrated information. South West The SEOs offer guidance on the critical issues, which could help to achieve sustainable growth and a more secure environmental future. -

J .. Incolnshire

GRO J.. INCOLNSHIRE. {KELLY'S GROCERS & TEA DEALERS continued. Green Edward, Roman bank, Skcgness Holgate Samuel, Fulstow, Louth Ferreby John, Barrow•on-Humber Green James H. 22 Station st. Spalding Holland Jas. Halfleet, Market Deeping Fidell James, Worlaby 8.0 Green John, Bolingbroke, Spilsby Holland William H. Swineshead, hoston Fields Mrs Elizabeth, 5 Cannon street, Green John, 70 London road, Grantham Holhngsworth John, Priestgate, Barton- Northgate, Louth Greenaway Reuben, New road, Sutton on-Humber Field son Fredk. Willoughton, Lincoln Bridge, Wisbech Holmes, Rosser & Co. 2 Bailgate, Lincoln Fife Wm.'fhos. 97 Guilford st. Grimsby tlireetham Mrs. M. Swineshead, Boston Holmes George Clark, Wragby Fillingham Mrs. Catherine, East street, Griffin & Boothby, 28 High st. Spalding Holmes John, South Kyme, Lincoln Crow land, Peterb~Jrough Grundy Mrs. H. Willingham, Gainsbro' Holmes John George, Hundleby, Spilsby tFillingham Joseph G.Market pl.Bourne Gummerson James, 20 Market pl. Brigg Holmes John Thomas, IS High street k Finn Stpbn.N.so Donington st.Grimsby Gunson Miss Mary Jane, West st. Alford I Red Lion street, Stamford Fisher F. J. Corringham, Gainsboro' Hackett Hy. I~ St. Martin's, Stamford Holmes R. M. I76 Victoria st. Grimsby Fixter Mrs. Eliza, Shawould, Lincoln Ha!!gitt H. South Killingholme, Ulceby Holmes Samuel, Heckington S.O !<'!etcher & Sons, Market place, Long Haggitt Wesley, Thornton Curtis,Ulceby Holmes William, Donington, Spalding Button, Wisbech; & at High street, Haigh Mrs. Ada, Haxey, Doncaster Holt Mrs. S.A. Scunthorpe, Doncaster Holbeach Hainsworth William, Salttleetby All Home & Colonial Stores Limited, 24 Fletcher Ha'l"ry V. Gedney, Holbeach Saints, Louth Victoria street, Grimsby Fletcher John, Belch ford, Horncastle Halford Henry, Rippingale, Bourne Hood John Dales, 40 Union street, Louth Fletcher J. -

POST OFFICE LINCOLNSHIRE • Butche Rt;-Continued

340 POST OFFICE LINCOLNSHIRE • BuTCHE Rt;-continued. Evison J. W alkergate, Louth Hare R. Broughton, Bri~g · Cocks P. Hawthorpe, Irnham, Bourn Farbon L. East street, Horncastle Hare T. Billingborough, Falkingbam Codd J. H. 29 Waterside north, Lincoln Featherstone C. S. Market place, Bourn Hare T. Scredington, Falkingham Coldren H. Manthorpe rood, Little Featherstone J. All Sai,nts' street & High Hare W. Billingborough, Falkingharn Gonerby, Grantham street, Stamford Harmstone J. Abbey yard, Spalding tf Cole J • .Baston, Market Deeping Feneley G. Dorrington, Sleaford Harr G. All Saints street, Stamford Cole W. Eastgate, Louth Firth C. Bull street, Homcastle Harrison B. Quadring, Spalding Collingham G. North Scarle, N ewark Fish .J. West l"erry, Owston Harrison C. Scopwick, Sleaford · Connington E. High street, Stamford Fisher C. Oxford street, Market Rasen Harrison G. Brant Broughton, Newark Cook J. Wootton, Ulceby Fisher H. Westg11te, New Sleaford Harrison H. Bardney, Wragby Cooper B. Broad street, Grantham Fisher J. Tealby, Market Rasen Harrison R. East Butterwick, Bawtry f Cooper G. Kirton-in-Lindsey Folley R. K. Long Sutton Harrison T. We1ton, Lincoln Cooper J. Swaton, Falkingham Forman E. Helpringham, Sleaford Harrison W. Bridge st. Gainsborougb Cooper L • .Barrow-on-Humber, Ulceby Foster E. Caistor HarrisonW.Carlton-le-Moorland,Newrk Cooper M. Ulceby Foster Mrs. E. Epworth Harrod J, jun. Hogsthorpe, Alford Cooper R. Holbeach bank, Holbeach Foster J. Alkborough, Brigg Harvey J. Old Sleaford Coopland H. M. Old Market lane, Bar- Foster W. Chapel street, Little Gonerby, Harvey J. jun. Bridge st. New Sleaford ton-on~Humbm• Grantham Hastings J. Morton-by-Gainsborough CooplandJ.Barrow-on-Humber,Ulceby Foster W.