The View from the Oval Office: the Audience Effects of Presidential Appearances on Entertainment Talk Shows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director.—Michael Mastrian Deputy Director.—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator.—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinator.—Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director.—Tina Tate Deputy Director.—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistant for Administrative Operations.—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations.—Andy Elias Assistants: Gerald Rupert, Kimberly Oates EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

House of Cards Aids Typhoon Victims

'House of Cards' team organizing aid for typhoon victims - baltimoresun.com http://www.baltimoresun.com/entertainment/tv/z-on-tv-blog/bal-house-of-... www.baltimoresun.com/entertainment/tv/z-on-tv-blog/bal-house-of-cards--aid-typhoon-victims- 20131115,0,7088713.story Donations accepted through Wednesday in Baltimore area By David Zurawik The Baltimore Sun 8:00 PM EST, November 15, 2013 With filming for Season 2 completed last week, members of the team making "House of Cards" in advertisement Baltimore are focusing their energies on helping the victims of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Through Wednesday, workers on the show will be loading donated goods onto a tractor trailer that will be driven to Los Angeles and shipped to the Philippines, according to Rehya Young, assistant locations manager for the Netflix series produced by Media Rights Capital. "We'll be accepting donations until Wednesday, Nov. 20, which will give us time to pack the truck properly and get it to L.A. on time," said Young. The truck will be parked at the show's offices in Edgewood, MD. Those who think they might have something to donate can email Young: [email protected]. She will provide directions or make arrangements if the donor cannot transport the items. The "House of Cards" team is co-ordinating its relief efforts with Operation USA, which will be shipping the goods from Los Angeles to the Philippines. Those who want to make a financial donation through Operation USA can do so here. Several area businesses and unions that work with and on the series have already made contributions, according to Young. -

Toward a Broadband Public Interest Standard

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2009 Toward a Broadband Public Interest Standard Anthony E. Varona University of Miami School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Anthony E. Varona, Toward a Broadband Public Interest Standard, 61 Admin. L. Rev. 1 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2009 Toward a Broadband Public Interest Standard Anthony E. Varona Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Communications Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons ARTICLES TOWARD A BROADBAND PUBLIC INTEREST STANDARD ANTHONY E. VARONA* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................. 3 1. The Broadcast Public Interest Standard ............................................ 11 A. Statutory and Regulatory Foundations ...................................... 11 B. Defining "Public Interest" in Broadcasting .......................... 12 1. 1930s Through 1960s-Proactive Regulation "to Promote and Realize the Vast Potentialities" of B roadcasting .................................................................. 14 a. Attempts at Specific Requirements: The "Blue Book" and the 1960 Programming Statement ........... 16 b. More Specification, the Fairness Doctrine, and Noncommercial Broadcasting ................................... 18 c. Red Lion BroadcastingCo. -

Political Accountability, Communication and Democracy: a Fictional Mediation?

Türkiye İletişim Araştırmaları Dergisi • Yıl/Year: 2018 • Özel Sayı, ss/pp. e1-e12 • ISSN: 2630-6220 DOI: 10.17829/turcom.429912 Political Accountability, Communication and Democracy: A Fictional Mediation? Siyasal Hesap Verebilirlik, İletişim ve Demokrasi: Medyalaştırılmış bir Kurgu mu? * Ekmel GEÇER 1 Abstract This study, mostly through a critical review, aims to give the description of the accountability in political communication, how it works and how it helps the addressees of the political campaigns to understand and control the politicians. While doing this it will also examine if accountability can help to structure a democratic public participation and control. Benefitting from mostly theoretical and critical debates regarding political public relations and political communication, this article aims (a) to give insights of the ways political elites use to communicate with the voters (b) how they deal with accountability, (c) to learn their methods of propaganda, (d) and how they structure their personal images. The theoretical background at the end suggests that the politicians, particularly in the Turkish context, may sometimes apply artificial (unnatural) communication methods, exaggeration and desire sensational narrative in the media to keep the charisma of the leader and that the accountability and democratic perspective is something to be ignored if the support is increasing. Keywords: Political Communication, Political Public Relations, Media, Democracy, Propaganda, Accountability. Öz Bu çalışma, daha çok eleştirel bir yaklaşımla, siyasal iletişimde hesap verebilirliğin tanımını vermeyi, nasıl işlediğini anlatmayı ve siyasal kampanyaların muhatabı olan seçmenlerin siyasilerin sorumluluğundan ne anladığını ve onu politikacıları kontrol için nasıl kullanmaları gerektiğini anlatmaya çalışmaktadır. Bunu yaparken, hesap verebilirliğin demokratik toplumsal katılımı ve kontrolü inşa edip edemeyeceğini de analiz edecektir. -

Biden Visits SNHU, Hopes to Revive the Breast CANCER AWARENESS MONTH "American Dream"

"Keep it positive" -Timothy Parent Volume XVI, Issue II October 21st 2008 Manchester, NH OCTOBER IS: Biden Visits SNHU, Hopes to Revive the BREAST CANCER AWARENESS MONTH "American Dream" Hampshire, stating, “1,400 Aimee Terravechia New Hampshire residents Staff Writer have lost their houses within the last quarter alone.” Many of these figures resonated After visiting the American Biden, both he and Obama are with New Hampshire resi- Legion Hall, Post 7, in Roches- working to address these con- dents who are beginning to ter earlier in the day, Senator Joe cerns by focusing on the econ- feel the financial pinch more Biden, running mate of Barack omy and job creation. and more. Obama, visited Southern New “Our plan,” Biden said, “is Biden also talked at length Hampshire University’s campus to create over two million new about what he considers to be on Monday, October 13th. The jobs averaging at about $50,000 an “attack” campaign being event attracted community mem- per year.” Biden began discuss- run by Senator McCain. The photo provided by Google bers and students alike, drawing ing the impact that these plans crowd, filled with Obama approximately 900 guests. would have on New Hampshire What's Inside? supporters sporting shirts Senator Joe Biden Pages After short speeches by residents. Nine-thousand of that read: McCan’t began News 1-11 both Dave Hendrie, a field orga- these new jobs, he said, would be “booing” at the mention of Obama, Biden said, “McCain wants Business 12 nizer for the Obama campaign created in the Granite State. -

Chinese President Xi's September 2015 State Visit

Updated October 7, 2015 Chinese President Xi’s September 2015 State Visit Introduction September 26 to 28, President Xi visited the United Nations headquarters in New York for the 70th meeting of the U.N. Chinese President Xi Jinping (his family name, Xi, is General Assembly. Among other things, he announced pronounced “Shee”) made his first state visit to the United major new Chinese contributions to U.N. peacekeeping States, and his second U.S. visit as president, in September operations and military assistance to the African Union. 2015. He was the fourth leader of the People’s Republic of China to make a state visit to the United States, following in Outcomes Documents the footsteps of Li Xiannian in 1985, Jiang Zemin in 1997, and Hu Jintao in 2011. The visit came at a time of tension As has been the practice since 2011, the two countries did in the U.S.-China relationship. The United States has been not issue a joint statement. Instead, they conveyed critical of China on such issues as its alleged cyber outcomes through the two presidents’ joint press espionage, slow pace of economic reforms, island building conference; a Joint Presidential Statement on Climate in disputed waters in the South China Sea, harsh treatment Change; identical negotiated bullet points on economic of lawyers, dissidents, and ethnic minorities, and pending relations and cyber security, issued separately by each restrictive legislation on foreign organizations. Even as the country; and bullet points on other issues, issued separately White House prepared to welcome President Xi, it was and not identical in wording. -

Alternative Perspectives of African American Culture and Representation in the Works of Ishmael Reed

ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of Zo\% The requirements for IMl The Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature by Jason Andrew Jackl San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Jason Andrew Jackl 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Alternative Perspectives o f African American Culture and Representation in the Works o f Ishmael Reed by Jason Andrew Jackl, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English Literature at San Francisco State University. Geoffrey Grec/C Ph.D. Professor of English Sarita Cannon, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED Jason Andrew JackI San Francisco, California 2018 This thesis demonstrates the ways in which Ishmael Reed proposes incisive countemarratives to the hegemonic master narratives that perpetuate degrading misportrayals of Afro American culture in the historical record and mainstream news and entertainment media of the United States. Many critics and readers have responded reductively to Reed’s work by hastily dismissing his proposals, thereby disallowing thoughtful critical engagement with Reed’s views as put forth in his fiction and non fiction writing. The study that follows asserts that Reed’s corpus deserves more thoughtful critical and public recognition than it has received thus far. To that end, I argue that a critical re-exploration of his fiction and non-fiction writing would yield profound contributions to the ongoing national dialogue on race relations in America. -

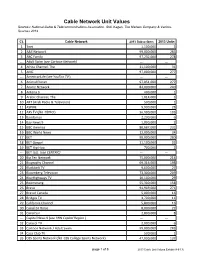

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, the Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, The Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013 Ct. Cable Network 2013 Subscribers 2013 Units 1 3net 1,100,000 3 2 A&E Network 99,000,000 283 3 ABC Family 97,232,000 278 --- Adult Swim (see Cartoon Network) --- --- 4 Africa Channel, The 11,100,000 31 5 AMC 97,000,000 277 --- AmericanLife (see YouToo TV ) --- --- 6 Animal Planet 97,051,000 277 7 Anime Network 84,000,000 240 8 Antena 3 400,000 1 9 Arabic Channel, The 1,014,000 3 10 ART (Arab Radio & Television) 500,000 1 11 ASPIRE 9,900,000 28 12 AXS TV (fka HDNet) 36,900,000 105 13 Bandamax 2,200,000 6 14 Bay News 9 1,000,000 2 15 BBC America 80,687,000 231 16 BBC World News 12,000,000 34 17 BET 98,000,000 280 18 BET Gospel 11,100,000 32 19 BET Hip Hop 700,000 2 --- BET Jazz (see CENTRIC) --- --- 20 Big Ten Network 75,000,000 214 21 Biography Channel 69,316,000 198 22 Blackbelt TV 9,600,000 27 23 Bloomberg Television 73,300,000 209 24 BlueHighways TV 10,100,000 29 25 Boomerang 55,300,000 158 26 Bravo 94,969,000 271 27 Bravo! Canada 5,800,000 16 28 Bridges TV 3,700,000 11 29 California Channel 5,800,000 16 30 Canal 24 Horas 8,000,000 22 31 Canal Sur 2,800,000 8 --- Capital News 9 (see YNN Capital Region ) --- --- 32 Caracol TV 2,000,000 6 33 Cartoon Network / Adult Swim 99,000,000 283 34 Casa Club TV 500,000 1 35 CBS Sports Network (fka CBS College Sports Network) 47,900,000 137 page 1 of 8 2013 Cable Unit Values Exhibit (4-9-13) Ct. -

NATPE 2013 Tuesday, January 29, 2013 Click For

join the family this fall 20TH TV 3376 BRIAN S. TOP HAT BANNER MECHANICAL BUILT AT 100% MECH@ 100% 9.875" X 1.25" 9.625"W X 1"H SHOW DAILY NATPE • MIAMI BEACH TUESDAY, JANUARY 29, 2013 CONTENT INDUSTRY client and prod special info: # job# artist issue/ time pub post date (est) insert/ line Sinead Harte size air date screen 323-963-5199 ext 220 CHANGE 8240 Sunset Blvd CREATES bleed trim live Los Angeles, CA 90046 DEBATEBY ANDREA FREYGANG CERTAINBY CHARLOTTE LIBOV ideo might have killed ra - dio, as the first song aired on echnology is changing view- VMTV implied, but not every- ing habits and the TV industry one is certain that the internet is Tmust keep pace by reinventing going to cause TV’s demise. In itself, much as music industry did the opening session of NATPE, in the wake of the seismic changes as panelists debated the impact that nearly destroyed that indus- of social media and the internet try, observed David Pakman, who on the TV industry, audience re- led the opening panelA-004 at NATPE 1537F CHRISTINA SCHIERMANN PHOTO BY ALEX MATTEO BY PHOTO 1/4"=1' action was mixed. on Monday. Game changing or not? That was the topic under consideration Monday when a keynote panel of LAX FLIGHT PATH 9.01.08 N/A 4c “I think Facebook is a better experts voiced opinions about the impact of digital distribution. Among those weighing in were, In answer to the question competitor to TV than YouTube. from left to right, Kevin Beggs, Lionsgate Television Group president; TheBlaze’s Betsy Morgan, Will Disruption Choke250' the w TeleviX 65'- h 9.18.08 SUNDAY 150 It’s a very interesting debate president & chief strategy officer; and Aereo’s Chet Kanojia, founder and CEO sion Business Models?,68.75" the Xpanel 17.875" 62.5" X 16.25" ALL to have,” said Fiona Dawson, a SEE CHANGE, P. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Archive Name ATAS14_Corp_140003273 MECH SIZE 100% PRINT SIZE Description ATAS Annual Report 2014 Bleed: 8.625” x 11.1875” Bleed: 8.625” x 11.1875” Posting Date May 2014 Trim: 8.375” x 10.875” Trim: 8.375” x 10.875” Unit # Live: 7.5” x 10” LIve: 7.5” x 10” message from THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER At the end of 2013, as I reflected on my first term as Television Academy chairman and prepared to begin my second, it was hard to believe that two years had passed. It seemed more like two months. At times, even two weeks. Why? Because even though I have worked in TV for more than three decades, I have never seen our industry undergo such extraordinary — and extraordinarily exciting — changes as it has in recent years. Everywhere you turn, the vanguard is disrupting the old guard with an astonishing new technology, an amazing new show, an inspired new way to structure a business deal. This is not to imply that the more established segments of our industry have been pushed aside. On the contrary, the broadcast and cable networks continue to produce terrific work that is heralded by critics and rewarded each year at the Emmys. And broadcast networks still command the largest viewing audience across all of their platforms. With our medium thriving as never before, this is a great time to work in television, and a great time to be part of the Television Academy. Consider the 65th Emmy Awards. The CBS telecast, hosted by the always-entertaining Neil Patrick Harris, drew our largest audience since 2005.