KILMARNOCK ACADEMY: FORMER PUPILS Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir David P. Cuthbertson (190&1989)

Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 63, No. 1 https://www.cambridge.org/core . IP address: 170.106.34.90 , on 03 Oct 2021 at 14:36:48 , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms . https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN19900085 DAVlD P. CUTHBERTSON (Facing p. I) Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition (1990). 63, 14 1 https://www.cambridge.org/core Obituary Notice SIR DAVID P. CUTHBERTSON (190&1989) . IP address: David Paton Cuthbertson CBE, MD, DSc, FRSE, a past President of the Nutrition Society, a previous Editor of the British Journal of Nutrition, and for 20 years Director of the Rowett Research Institute, died on 15 April 1989-a few weeks before his 89th birthday. He was born in Kilmarnock, Ayrshire, and educated at Kilmarnock Academy 170.106.34.90 and the University of Glasgow from which he first graduated BSc in Chemistry in 1921, having been awarded the Doby-Smith gold medal. On graduation the Scottish Board of Agriculture awarded him a research scholarship to undertake work in chemistry in Dundee. , on However, this was initially deferred and then declined because he was influenced to study 03 Oct 2021 at 14:36:48 medicine by Professor E. P. Cathcart, FRS, well-known for his work in nutrition. He graduated MBChB in 1926, having won the Hunter medal in Physiology and a Strang-Steel scholarship for research. The latter enabled him to carry out research during vacations which led to his first publication, on ‘The distribution of phosphorus in muscle’, in the Biochemical Journal in 1925. -

DNA Status for Mcm Clan Families of Ayrshire Origins July 2009 Barr

DNA Status for McM Clan Famil ies of Ayrshire origins July 2009 blue=Dalmellington pattern; purple =Ayrshire/Co Antrim pattern; green= Ayrshire/Derry pattern; Yellow =DNA samples in process; nkd=no known male descendants Edinburgh families w Ayr origin CF 40 Wm m 1805 in Barr CF 45 Thomas b c a 1811 CF 46 James b 1820s CF 47 Thomas b 1770 (Galston ) Ayr/St Quivox CF 30 Thomas b ca 1770 CF 50 Alexander b ca 1780 CF 27 Andrew b ca 1780 Coylton/ Craigie & Sorn CF 23 John b 1735 Maybole CF 16 Thomas b 1770 (in Paisley 1793-5, in Maybole 1797-1806; Thomas b 1802=> Kilmarnock 1828, Galston 1830; Maybole 1832) CF 42 James b 1750/60 CF 7 Thomas b 1750/60 Dalmellington CF 41 Thomas b 1725/35 CF 19/CF 113 Wm b c 1690 CF 52 Adam b 1806 CF 104: David b 1735 (to Kirkm’l 1761) CF 45 Thomas b 1811 Kirkoswald CF 40 William m 1805 Barr CF 37 Thomas m 1775 CF 38 Alexander b 1770 Kirkmichael CF 12 Andrew b 1771 CF 28: John md abt 1760 Agnes Telfer (desc in Ayr by 1827) CF 18 Thomas b 1750/60 Dam of Girvan Barnshean CF 14: William md ca CF 11 James b 1825 1735, Woodhead of CF 5 : William md 1750 Eliz Mein Girvan (nkd) (nkd) Straiton Barr CF 48 Wm md 1777 Dalmell . (nkd) CF 4 James b 1743 md 1768 Dailly, CF 39 James Dailly b Dailly, md 1800 CF 1 John of Dailly md 1744 Maybole Barr CF 21 Hugh b 1743 CF 5David md 1782 (nkd) =>Ladyburn, Kirkmich ’l CF 14 Wm b 1701 (nkd) Wigtonshire (south of Ayrshire) CF 22/32 Thomas m 1720 CF 15 John & Robert of Co Down came to Wigtonshire ca 1800 The above map shows most of the McMurtrie Clan Families of Ayrshire Scotland as found in the parish registers that can be traced down to modern times. -

LEADERSHIP WORK STREAM the SWEIC Leadership

LEADERSHIP WORK STREAM The SWEIC leadership work stream leads are exploring ways to develop the leadership capacity of staff across the collaborative. Within this framework, members of staff within the SWEIC have identified leadership practice that other staff from across the RIC can tap in to. Please promote the opportunities contained within this booklet within your establishments. If you would like to attend any of the professional learning opportunities, please contact [email protected] who will be able to advise on the best possible way to arrange to participate in these fantastic opportunities. Summary of opportunities Patna Primary Developing learning through play in primary 1 Park School Nurture and inclusion throughout the whole school approach to music development and instruction Patna Primary Nurture P1 play pedagogy Rephad Primary Leadership Presentation Loudoun Academy Communication Centre Loudoun Academy Engineering Pathways James Hamilton ECC Implementation of 1140 hours Annanhill Primary Multiple Opportunities Ardrossan Academy Middle Leadership Stewarton Academy STEM Blacklands Primary Leadership of Opportunity Greenmill Primary School Multiple Opportunities Kilmarnock Academy Relationships Kilmarnock Academy Pupil Equity Fund Doon Academy Learner Pathways Garnock Community Campus Quality Improvement Framework for Mental Health Garnock Community Campus Literacy across Learning Forehill Primary Using Clicker 7 to support the teaching of writing Doon Academy Action Research Approaches DEVELOPING LEARNING THROUGH -

Scottish Sun Article

1S Friday, September 3, 2010 27 Tribute to bike hero MILITARY chiefs last night paid tribute to a ScotsNavy hero killed in ahorror bike smash. Petty Officer Jamie Adam, 28, died after he and cop Chris Bradshaw’s motorcycles crashed during the Manx Grand Prix on the Isle of Man. Chris, 39, of Tamworth, Staffordshire, lost his fight for life in hospital. Aspokesman for HMS Sultan, where Jamie, of Prestwick, had just com- pleted an air engineering course, said he had been “popular and profes- sional”, and added: “His tragic loss is felt deeply.” BIRTHDAY BOY ...Brian ICAESAR LIGHT Abronze Roman lan- TROOPS SET terndug up in afield near Sudbury, Suffolk, is the only one to have been FOR MARCH found in Britain. out Tartan Army drum lind youngster gets to try TO VICTORY BIG BANG THEORY ...b FRIENDS UNITED. .. TARTAN Army troops are on the From GRAEME DONOHOE Tartan Army Tartan Army Reporter, Euro 2012 march —and confident at the Gile Scotland will bounce back from last in Vilnius, Lithuania kids’ home month’s friendly defeat in Sweden. Refuse collection worker Brian THE Tartan Army carried out Mason hopes Craig Levein’s Brave- ahearts and minds mission hearts will deliver him the perfect birthday present. at an orphanage in Vilnius Brian, from Aber- yesterday —after local press deen, said: “I’m 50 warned our Scots fans are a on the day of the game, so I’m hoping SECURITY THREAT. Scotland will help Lithuanian media caused a me celebrate it stir about our fun-lovin’ fans properly. when they suggested more “I reckon theboys cops would have to be drafted will win 2-0 —no GIFT ...Carey hands over shirt problem. -

East Ayrshire Local Development Plan Action Programme August 2019

East Ayrshire Local Development Plan Action Programme August 2019 update 1 Kilmarnock settlement wide placemaking map 2 Kilmarnock town centre placemaking map 3 Action Policy/Proposal Action Required Persons Responsible Timescales Progress as at August 2019 No (2017) 1 Development of Consideration of new Hallam Land Management/house 2017-2022 Renewal of Planning Permission in Principle Northcraig site 319H & planning application builders for Proposed Change of Use from Agricultural site 362M (Southcraig and implementation to Residential Use incorporating means of Drive) by Hallam Land access, open space, landscaping and Management. associated works was approved in 2015 Further application (17/0355/AMCPPP) was approved in February 2018. Development is now underway on site. The 1st phase of the development will involve the erection of 136 residential units by Barratt Homes. A further 2 phases will be developed in the future. No timescales are available for the 2 remaining phases at present. Discussions are ongoing with respect to the future development of site 262M. 2 Development of site A partnership Land owners/developer(s) 2020-2025 Small part of the site has been granted 152B at Meiklewood, between all owners approval for vehicle storage and office North Kilmarnock is required. accommodation associated with existing Alternatively, a single business on the site developer to take ownership of whole Development proposals expected to come site and develop forwards now that site 319H (Northcraigs) has primarily for commenced development and access through business/industrial site 153B (Rowallan Business Park) has been use. High resolved. infrastructure costs may mean the site is The long term strategy for the north of a longer term Kilmarnock, including this site, will be a key prospect and may issue to be explored through the preparation require a of LDP2. -

The History of the First Presbyterian Church Charlottesville, Virginia

The History of the First Presbyterian Church Charlottesville, Virginia “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself.” Luke 10:27 Robert E. Simpson Introduction Like many organizations with a time-honored history, the church documents its past in the tangibility of faces, official papers, portraits, material objects, and buildings. Expressed algebraically, history is the evidence of people added to places divided by time, a formula consciously present here. History, says the philosopher, counts Time not by the Hours but by the Ages. Time therefore is a vehicle by which each of us has traveled, history is knowing where that vehicle has been. The story of the First Presbyterian Church finds its beginnings back into the 18th century. This history will introduce you to many past and present citizens of Charlottesville and Albemarle County, and is but a speck in the story of the Church. To many we have not known, yet we have a sense of companionship. And, then there are those who we have known, and loved, and shared in Christian fellowship. For this history, I have relied heavily on primary sources: minutes of the various church courts; minutes of organizations of the church; letters; personal and written interview. In selecting items to be included, I have tried to make them representative of the life of the whole church. I realize that voices from the grave are mute, however, and items from the past which should have been included are known only to that great “cloud of witnesses” and to the Sovereign God. -

Men's 400 Metres

2016 Müller Anniversary Games • Biographical Start List Men’s 400 Metres Sat / 14:49 2016 World Best: 43.97 LaShawn Merritt USA Eugene 3 Jul 16 Diamond League Record: 43.74 Kirani James GRN Lausanne 3 Jul 14 Not a Diamond Race event in London Age (Days) Born 2016 Personal Best 1, JANEŽIC Luka SLO – Slovenia 20y 252d 1995 45.22 45.22 -16 Slovenian record holder // 200 pb: 20.67w, 20.88 -15 (20.96 -16). ht World Youth 200 2011; sf WJC 200/400 2014; 3 under-23 ECH 2015; 1 Balkan 2015; ht WCH 2015; sf WIC 2016; 5 ECH 2016. 1 Slovenian indoor 2014/2015. 1.92 tall In 2016: 1 Slovenian indoor; dq/sf WIC (lane); 1 Slovenska Bistrica; 1 Slovenian Cup 200/400; 1 Kranj 100/200; 1 Slovenian 200/400; 2 Madrid; 5 ECH 2, SOLOMON Steven AUS – Australia 23y 69d 1993 45.44 44.97 -12 2012 Olympic finalist while still a junior // =3 WJC 2012 (4 4x400); 8 OLY 2012; sf COM 2014. 1 Australian 2011/2012/2014/2016. 1 Australian junior 2011/2012. Won Australian senior title in 2011 at age 17, then retained it in 2012 at 18. Coach-Iryna Dvoskina In 2016: 1 Australian; 1 Canberra; 1 Townsville (Jun 3); 1 Townsville (Jun 4); 3 Geneva; 4 Madrid; 2 Murcia; 1 Nottwil; 2 Kortrijk ‘B’ (he fell 0.04 short of the Olympic qualifying standard of 45.40) 3, BERRY Mike USA – United States 24y 226d 1991 45.18 44.75 -12 2011 World Championship relay gold medallist // 1 WJC 4x400 2010. -

Sample Download

DUNDEE UNITED ON THIS DAY JANUARY 11 Dundee United On This Day THURSDAY 1st JANUARY 2015 A great start to 2015 as United thump Dundee in the new year derby at Tannadice, in front of 13,000 fans. Stuart Armstrong deflects a Chris Erskine shot into the Dundee net in the first minute, and an Erskine strike and a Gary Mackay-Steven double make it 4-1 by half-time. Jaroslaw Fojut and Charlie Telfer add two more in the second half, and the 6-2 final score puts United third in the Premiership, just three points behind Aberdeen and two behind Celtic. WEDNESDAY 1st JANUARY 1913 Dumbarton are the new year’s day visitors at Tannadice, but, although a railway special brings 300 fans through from the west coast, The Dundee Evening Telegraph reports that very few of them make it to the game, presumably as a side effect of their new year celebrations. The Dumbarton players, on the other hand, show no sign of any hangover as they start brightly in a match full of chances, but Dundee Hibernian – as the club were called before changing their name to United – come back from 3-1 down to draw 3-3. THURSDAY 2nd JANUARY 1958 United beat East Stirling 7-0. Jimmy Brown and Wilson Humphries both grab doubles, and Allan Garvie, Willie McDonald and Joe Roy score once each. Twenty-year-old Aberdonian defender Ron Yeats makes his debut in the match. He features prominently for United for four seasons, before, in 1961, he’s sold for £30,000 to Liverpool, where he becomes hugely influential and plays over 450 games. -

Hugh Mcilvanney: Sportswriter Who Went Beyond the Game to Seek a Higher Truth of the Human Condition

28/01/2019 Hugh McIlvanney: sportswriter who went beyond the game to seek a higher truth of the human condition Academic rigour, journalistic flair Hugh McIlvanney: sportswriter who went beyond the game to seek a higher truth of the human condition January 25, 2019 4.22pm GMT Author Richard Haynes Professor of Media Sport, University of Stirling Britain’s greatest sportswriter at the Football Writers’ Association tribute night in 2018. John Walton/PA Wire/PA Images Among all the tributes to the celebrated sports journalist Hugh McIlvanney, who has died aged 84, you will find one recurring theme: that in his work, the Scots-born reporter, writer and broadcaster transcended his genre. Greater by far than his renowned and extensive contact book, his insights based on a decades-long love of sport or his ability to get close to the sporting greats, was his ability – when writing about one sport or another – to impart some greater truth about the human condition. In 1991, McIlvanney attempted to reflect on the role of the sports journalist in the documentary Sportswriter as part of the BBC’s Arena series. His opening narrative revealed some inner conflicts he himself felt on the role of the “fan with a typewriter”, a moniker often thrown at a very insular job. He said: After more than 30 years of writing on sport it is still possible to be assailed by doubts about whether it really is a proper job for a grown person. But I console myself with the thought that it is easier to find a kind of truth in sport than it is, for example, in the activities covered by political or economic journalists. -

Oracle: ORU Student Newspaper Oral Roberts University Collection

Oral Roberts University Digital Showcase Oracle: ORU Student Newspaper Oral Roberts University Collection 2-22-1974 Oracle (Feb 22, 1974) Holy Spirit Research Center ORU Library Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/oracle Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Higher Education Commons 'Show Me Jesus!' hqils tomorrow rhe by kot wolker And Roger has "friends" who are more than willing to show him Stone Productions, which pre- how to ease his troubled search- last serted Have A Nice Day ing. How about Drugs? As- 1, semester, will present Show Me! trology? Meditation? Somewhe¡e tomorrow evening at 8 in Howard there has to be an answer! Auditorium. Show Me! is a new Jon Stemkoski, Executive Di- kind of musical about Jesus, rector for Stone Productions, has which features Roger Sharp and featured several outstanding hits Vo|ume 9, NumbeT I7 ORAL RoBÉRTS UNIVERSITY, TULSA, oKLAHoMA Februory 22,1974 Stephanie Boosahda in the leading since Stone Productions began in roles with Jim Sharp, Michie Ep- April 1973. First featured was 1/'s stein, and Andy Melilli in the sup- Gettíng Late, a musical about porting roles. the end time and the Lord's re- Show Me! has the nerve to turn. Hal Lindsey, author of poke fun at the hypocrisy in the The Late Great Pianet Earth, was establishment churches of today. also featured. But it also shows how beautiful Stone Productions is a non- a life becomes when the Lord profit, student organization for is in it and when the person be- the purpose of witnessing about gins witnessing in earnest. -

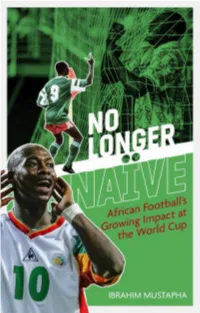

No Longer Naive SAMPLE.Pdf

Contents Acknowledgements 9 Introduction 10 1. Zaire – African Ignorance and Mobutu’s Influence 14 2. Colonialism, CAF and the Complicated Road to Recognition 29 3. Roaming Foxes and the Disgrace of Gijon 46 4. Morocco’s History Boys 63 5. Roger Milla’s Italian Job 72 6. All Eyes on the Eagles 88 7. Senegal’s Eastern Promise 106 8. Fresh Faces for Germany 125 9. The Fall and Rise of South African Football 142 10. The Tournament, Part I – Welcome to Africa 160 11. The Tournament, Part II – Black Stars Shine Bright 168 12. More Money, More Problems in Brazil 190 13. From Russia with Little Love 211 Epilogue 226 Statistics – The Complete Record of African Teams at the World Cup 231 Bibliography 252 1 Zaire – African Ignorance and Mobutu’s Influence THE WORLD Cup of 1974 may have been the tenth edition of the tournament but for many fans and observers of the global game, this would be their first experience of seeing a team from sub-Saharan Africa playing football at any level. The tournament had seen fleeting glimpses of Egypt and Morocco previously, but there was generally a greater familiarity with teams from the north of the continent due to its proximity to Europe, and the fact several players from the region had already migrated to European clubs. Zaire, on the other hand, was far further south than many in the global north would have even been aware of, let alone travelled to, and was certainly an unknown entity as far as football was concerned. However, it isn’t as though they had simply wandered in off the street to compete at the World Cup. -

The Trinitarian Ecclesiology of Thomas F. Torrance

The Trinitarian Ecclesiology of Thomas F. Torrance Kate Helen Dugdale Submitted to fulfil the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, November 2016. 1 2 ABSTRACT This thesis argues that rather than focusing on the Church as an institution, social grouping, or volunteer society, the study of ecclesiology must begin with a robust investigation of the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Utilising the work of Thomas F. Torrance, it proposes that the Church is to be understood as an empirical community in space and time that is primarily shaped by the perichoretic communion of Father, Son and Holy Spirit, revealed by the economic work of the Son and the Spirit. The Church’s historical existence is thus subordinate to the Church’s relation to the Triune God, which is why the doctrine of the Trinity is assigned a regulative influence in Torrance’s work. This does not exclude the essential nature of other doctrines, but gives pre-eminence to the doctrine of the Trinity as the foundational article for ecclesiology. The methodology of this thesis is one of constructive analysis, involving a critical and constructive appreciation of Torrance’s work, and then exploring how further dialogue with Torrance’s work can be fruitfully undertaken. Part A (Chapters 1-5) focuses on the theological architectonics of Torrance’s ecclesiology, emphasising that the doctrine of the Trinity has precedence over ecclesiology. While the doctrine of the Church is the immediate object of our consideration, we cannot begin by considering the Church as a spatiotemporal institution, but rather must look ‘through the Church’ to find its dimension of depth, which is the Holy Trinity.