Steve Reich's Clapping Music and the Yoruba Bell Timeline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents

THE CLEVELAND ORCHESTRA WHAT IS AN ORCHESTRA? Student Learning Lab for The Percussion Family 1 Table of Contents PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family ...................... 3 PART 2: Let’s Listen to Nagoya Marimbas ...................... 6 PART 3: Music Learning Lab ................................................ 8 2 PART 1: Let’s Meet the Percussion Family An orchestra consists of musicians organized by instrument “family” groups. The four instrument families are: strings, woodwinds, brass and percussion. Today we are going to explore the percussion family. Get your tapping fingers and toes ready! The percussion family includes all of the instruments that are “struck” in some way. We have no official records of when humans first used percussion instruments, but from ancient times, drums have been used for tribal dances and for communications of all kinds. Today, there are more instruments in the percussion family than in any other. They can be grouped into two types: 1. Percussion instruments that make just one pitch. These include: Snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, tambourine, triangle, wood block, gong, maracas and castanets Triangle Castanets Tambourine Snare Drum Wood Block Gong Maracas Bass Drum Cymbals 3 2. Percussion instruments that play different pitches, even a melody. These include: Kettle drums (also called timpani), the xylophone (and marimba), orchestra bells, the celesta and the piano Piano Celesta Orchestra Bells Xylophone Kettle Drum How percussion instruments work There are several ways to get a percussion instrument to make a sound. You can strike some percussion instruments with a stick or mallet (snare drum, bass drum, kettle drum, triangle, xylophone); or with your hand (tambourine). -

The Role of Bell Patterns in West African and Afro-Caribbean Music

Braiding Rhythms: The Role of Bell Patterns in West African and Afro-Caribbean Music A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Jonathan Saxon* Antelope Valley College Summary: These lessons aim to demonstrate polyrhythmic elements found throughout West African and Afro-Caribbean music. Students will listen to music from Ghana, Nigeria, Cuba, and Puerto Rico to learn how this polyrhythmic tradition followed Africans to the Caribbean as a result of the transatlantic slave trade. Students will learn the rumba clave pattern, cascara pattern, and a 6/8 bell pattern. All rhythms will be accompanied by a two-step dance pattern. Suggested Grade Levels: 9–12, college/university courses Countries: Cuba, Puerto Rico, Ghana, Nigeria Regions: West Africa, the Caribbean Culture Groups: Yoruba of Nigeria, Ga of Ghana, Afro-Caribbean Genre: West African, Afro-Caribbean Instruments: Designed for classes with no access to instruments, but sticks, mambo bells, and shakers can be added Language: English Co-Curricular Areas: U.S. history, African-American history, history of Latin American and the Caribbean (also suited for non-music majors) Prerequisites: None. Objectives: Clap and sing clave rhythm Clap and sing cascara rhythm Clap and sing 6/8 bell pattern Dance two-bar phrase stepping on quarter note of each beat in 4/4 time Listen to music from Cuba, Puerto Rico, Ghana, and Nigeria Learn where Cuba, Puerto Rico, Ghana, and Nigeria are located on a map Understand that rhythmic ideas and phrases followed Africans from West Africa to the Caribbean as a result of the transatlantic slave trade * Special thanks to Dr. Marisol Berríos-Miranda and Dr. -

Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

of renowned rhythm and blues artists from this same time period lip-synch- ing to their hit recordings. These three aaamc mission: collections provide primary source The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, materials for researchers and students preservation, and dissemination of materi- and, thus, are invaluable additions to als for the purpose of research and study of our growing body of materials on African American music and culture. African American music and popular www.indiana.edu/~aaamc culture. The Archives has begun analyzing data from the project Black Music in Dutch Culture by annotating video No. 9, Fall 2004 recordings made during field research conducted in the Netherlands from 1998–2003. This research documents IN THIS ISSUE: the performance of African American music by Dutch musicians and the Letter ways this music has been integrated into the fabric of Dutch culture. The • From the Desk of the Director ...........................1 “The legacy of Ray In the Vault Charles is a reminder • Donations .............................1 of the importance of documenting and • Featured Collections: preserving the Nelson George .................2 achievements of Phyl Garland ....................2 creative artists and making this Arizona Dranes.................5 information available to students, Events researchers, Tribute.................................3 performers, and the • Ray Charles general public.” 1930-2004 photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Collection) photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Visiting Scholars reminder of the importance of docu- annotation component of this project is • Scot Brown ......................4 From the Desk menting and preserving the achieve- part of a joint initiative of Indiana of the Director ments of creative artists and making University and the University of this information available to students, Michigan that is funded by the On June 10, 2004, the world lost a researchers, performers, and the gener- Andrew W. -

An Exploration of the Relationship Between Mathematics and Music

An Exploration of the Relationship between Mathematics and Music Shah, Saloni 2010 MIMS EPrint: 2010.103 Manchester Institute for Mathematical Sciences School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Reports available from: http://eprints.maths.manchester.ac.uk/ And by contacting: The MIMS Secretary School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Manchester, M13 9PL, UK ISSN 1749-9097 An Exploration of ! Relation"ip Between Ma#ematics and Music MATH30000, 3rd Year Project Saloni Shah, ID 7177223 University of Manchester May 2010 Project Supervisor: Professor Roger Plymen ! 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface! 3 1.0 Music and Mathematics: An Introduction to their Relationship! 6 2.0 Historical Connections Between Mathematics and Music! 9 2.1 Music Theorists and Mathematicians: Are they one in the same?! 9 2.2 Why are mathematicians so fascinated by music theory?! 15 3.0 The Mathematics of Music! 19 3.1 Pythagoras and the Theory of Music Intervals! 19 3.2 The Move Away From Pythagorean Scales! 29 3.3 Rameau Adds to the Discovery of Pythagoras! 32 3.4 Music and Fibonacci! 36 3.5 Circle of Fifths! 42 4.0 Messiaen: The Mathematics of his Musical Language! 45 4.1 Modes of Limited Transposition! 51 4.2 Non-retrogradable Rhythms! 58 5.0 Religious Symbolism and Mathematics in Music! 64 5.1 Numbers are God"s Tools! 65 5.2 Religious Symbolism and Numbers in Bach"s Music! 67 5.3 Messiaen"s Use of Mathematical Ideas to Convey Religious Ones! 73 6.0 Musical Mathematics: The Artistic Aspect of Mathematics! 76 6.1 Mathematics as Art! 78 6.2 Mathematical Periods! 81 6.3 Mathematics Periods vs. -

Making Your Classroom Go

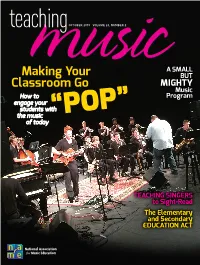

teaching OCTOBER 2015 VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2 A SMALL Makingmusicmusic Your BUT Classroom Go MIGHTY Music How to Program engage your students with the music “POP” of today TEACHING SINGERS to Sight-Read The Elementary and Secondary EDUCATION ACT QuaverFindOutAd_NAfME_Aug15.pdf 1 7/30/15 12:26 PM Find out what these districts already know... Quaver is revolutionizing music education! TM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Packed with nearly 1,000 Songs! Try 36 Lessons from our K-8 Curriculum! Just go to QuaverMusic.com/Preview and begin your FREE 30-day trial today! ©2015 QuaverMusic.com, LLC October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 contentsMUSIC EDUCATION ● ORCHESTRATING SUCCESS Music students learn cooperation, discipline, and teamwork. 28 Teachers and students alike can rock out and learn with pop music! FEATURES 24 TEACHING SINGERS 28 POP AND ROCK GOES 32 EL SISTEMA TODAY 38 SMALL SCHOOL, TO READ THE PROGRAM! José Antonio Abreu’s BIG EFFORT, Instructing students in Pop music connects creation has taken GREAT SUCCESS the art and techniques instantly with many root in the U.S. and Alexandria Hanessian’s of sight-singing can reap students. How can continues to grow small but mighty middle many rewards in your music educators use through programs such school program thrives choral rehearsals and it in their classrooms as the Corona Youth in Spencertown, beyond. to increase student Music Project and New York. engagement? Juneau Alaska Music Matters. Photo by Little Kids Rock. Photo by nafme.org 1 October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 Student composers contents (far left and right) work with teachers Conductor Marin Alsop 56 at Williamsville East works with students in High School. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:07 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2011 This essay offers broad reflection on some of the challenges faced by African composers of art music. The specific point of departure is the publication of a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar new anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Ghanaian pianist and scholar William Chapman Nyaho and published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. The anthology exemplifies a diverse range of See table of contents creative achievement in a genre that is less often associated with Africa than urban ‘popular’ music or ‘traditional’ music of pre-colonial origins. Noting the virtues of musical knowledge gained through individual composition rather than ethnography, the article first comments on the significance of the Publisher(s) encounters of Steve Reich and György Ligeti with various African repertories. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Then, turning directly to selected pieces from the anthology, attention is given to the multiple heritage of the African composer and how this affects his or her choices of pitch, rhythm and phrase structure. Excerpts from works by Nketia, ISSN Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi and Osman serve as illustration. 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Agawu, K. (2011). The Challenge of African Art Music. Circuit, 21(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Malay Gamelan: Approaches of Music Learning Through Community Music

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 11 ISSN: 2222-6990 Malay Gamelan: Approaches of music learning through Community Music Wong Huey Yi @ Colleen Wong Department of Music and Music Education, Faculty of Music and Performing Arts, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Malaysia. Christine Augustine Department of Music and Music Education, Faculty of Music and Performing Arts, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, Malaysia. DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i11/3562 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i11/3562 Abstract This paper looked into the role of Rhythm in Bronze (RiB), a local music group in Malaysia, in community music work practices that uses Malay gamelan as the medium. The research delved into the different aspects of the approaches used to enhance music learning through community music; particularly the activities used and how they relate to Vygotsky’s theory of socialization in learning. Community music gathers people from different backgrounds. Experiences and knowledge shared helps the community through the development in terms of personal growth, self- esteem and self-confidence. These terms are just some of the aspects that community music promotes, apart from music making. Along the process of community music, creativity and expression are important in music making, as this will further develop creative thinking skills among musicians. Qualitative approaches such as observation, interview, and group’s past work were used in this research to gather information and data on how music has been taught to children through community music. Social interaction has certainly shown a big role in developing children thinking and perceptions through the activities implemented. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

African Drumming in Drum Circles by Robert J

African Drumming in Drum Circles By Robert J. Damm Although there is a clear distinction between African drum ensembles that learn a repertoire of traditional dance rhythms of West Africa and a drum circle that plays primarily freestyle, in-the-moment music, there are times when it might be valuable to share African drumming concepts in a drum circle. In his 2011 Percussive Notes article “Interactive Drumming: Using the power of rhythm to unite and inspire,” Kalani defined drum circles, drum ensembles, and drum classes. Drum circles are “improvisational experiences, aimed at having fun in an inclusive setting. They don’t require of the participants any specific musical knowledge or skills, and the music is co-created in the moment. The main idea is that anyone is free to join and express himself or herself in any way that positively contributes to the music.” By contrast, drum classes are “a means to learn musical skills. The goal is to develop one’s drumming skills in order to enhance one’s enjoyment and appreciation of music. Students often start with classes and then move on to join ensembles, thereby further developing their skills.” Drum ensembles are “often organized around specific musical genres, such as contemporary or folkloric music of a specific culture” (Kalani, p. 72). Robert Damm: It may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music for the sake of enhancing the musical skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience of the participants. PERCUSSIVE NOTES 8 JULY 2017 PERCUSSIVE NOTES 9 JULY 2017 cknowledging these distinctions, it may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music (culturally specific rhythms, processes, and concepts) for the sake of enhancing the musi- cal skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience Aof the participants in a drum circle. -

Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE “Sound Come-Unity”: Post-9/11 Brown and the Politics of Intercultural Improvisation A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker September 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Liz Przybylski Copyright by Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker 2019 The Dissertation of Dhirendra Mikhail Panikker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Writing can feel like a solitary pursuit. It is a form of intellectual labor that demands individual willpower and sheer mental grit. But like improvisation, it is also a fundamentally social act. Writing this dissertation has been a collaborative process emerging through countless interactions across musical, academic, and familial circles. This work exceeds my role as individual author. It is the creative product of many voices. First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Professor Deborah Wong. I can’t possibly express how much she has done for me. Deborah has helped deepen my critical and ethnographic chops through thoughtful guidance and collaborative study. She models the kind of engaged and political work we all should be doing as scholars. But it all of the unseen moments of selfless labor that defines her commitment as a mentor: countless letters of recommendations, conference paper coachings, last minute grant reminders. Deborah’s voice can be found across every page. I am indebted to the musicians without whom my dissertation would not be possible. Priya Gopal, Vijay Iyer, Amir ElSaffar, and Hafez Modirzadeh gave so much of their time and energy to this project. -

St Luke's Farnworth BELL CASTING

St Luke’s Farnworth BELL CASTING by Geoffrey Poole In the earliest days they were cast in different sizes to produce different notes but no attempt was made to tune bells until the 16th Century with the advent of change ringing. In those times bells were roughly tuned – where the inside of the bell or the edge of the lip was chipped away with a hammer and chisel – eight bells could be tuned to an octave of eight notes. Some deprived communities used a hagiosideron, a shaped piece of metal which was struck in a similar way to a bell. Also again due to lack of money bellcotes were used instead of costly towers. A bell-cot, bell-cote or bellcote is a small framework and shelter for one or more bells. Bellcotes are most common in church architecture but are also seen on institutions such as schools. The bellcote may be carried on brackets projecting from a wall or built on the roof of chapels or churches that have no towers. The bellcote often holds the Sanctus bell that is rung at the consecration of the Eucharist. Bellcote is a compound noun of the words bell and cot or cote. Bell is self-explanatory. The word cot or cote is Old English, from the Germanic. It means a shelter of some kind, especially for birds or animals (see dovecote), a shed, or stall. Examples of bellcotes In order St Luke’s Farnworth Bell-cot at St Edmund's Church, Church Road, Wootton, Isle of Wight, England Church of England parish church of St Alban the Martyr, CharlesStreet, Oxford. -

Minimalism Post-Modernism Is a Term That Refers to Events After the So

Post-Modernism - Minimalism Post-Modernism is a term that refers to events after the so-called Modern period. The term suggests that we are now using what we learned in the “modern” period, but mixing it with ideas from the more distant past. A major movement within Post-Modernism is Minimalism Minimalism mixes some Eastern philosophical principles involving chant and meditation with simple tonal materials. Basic definition of Minimalism: sustained or repetitive use of simple (often tonal) materials. The movement began with LaMonte Young (b.1935); he used simple textures and consonant materials; often called trance music. Terry Riley (b.1935) is credited with first minimalist work In C (1964). The piece has repeated high C’s on piano maintaining simple pulse. Score has 53 short motives to be played by a group any size; players play all 53 figures, repeating as many times and as frequently as desired. Performance ends when all players are done with all 53 figures. Because figures change in content, there is subtle but constantly shifting texture all the time. Steve Reich (b. 1936) prefers to call his music “Structural” not minimal. His music is influenced by his study of African drumming. Some of his early works use phasing, where a tape loop is set up: the tape records first sounds made by performer; then plays them back while performer continues to play. More layers are added, and gradually live sounds get ahead of play-back. Effect can be hypnotic: trance-like. Violin Phase (1967) is example. In Mid-70’s Reich expanded his viewpoint and his ensemble: Music for 18 Musicians is a little like In C, but there is much more variation in patterns.