Randomized Controlled Trial of a Natural Food-Based Fiber Solution to Prevent Constipation in Postoperative Spine Fusion Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Model Answer

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOARD OF TECHNICAL EDUCATION (Autonomous) (ISO/IEC - 27001 - 2005 Certified) MODEL ANSWER WINTER– 18 EXAMINATION Subject Title: PHARMACEUTICAL CHEMISTRY-l Subject Code: 0806 ________________________________________________________________________________________ Important Instructions to examiners: 1) The answers should be examined by key words and not as word-to-word as given in the model answer scheme. 2) The model answer and the answer written by candidate may vary but the examiner may try to assess the understanding level of the candidate. 3) The language errors such as grammatical, spelling errors should not be given more Importance (Not applicable for subject English and Communication Skills. 4) While assessing figures, examiner may give credit for principal components indicated in the figure. The figures drawn by candidate and model answer may vary. The examiner may give credit for anyequivalent figure drawn. 5) Credits may be given step wise for numerical problems. In some cases, the assumed constant values may vary and there may be some difference in the candidate’s answers and model answer. 6) In case of some questions credit may be given by judgement on part of examiner of relevant answer based on candidate’s understanding. 7) For programming language papers, credit may be given to any other program based on equivalent concept. Page no.1/28 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOARD OF TECHNICAL EDUCATION (Autonomous) (ISO/IEC - 27001 - 2005 Certified) MODEL ANSWER WINTER– 18 EXAMINATION Subject Title: PHARMACEUTICAL CHEMISTRY-l Subject Code: 0806 ________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 ANSWER ANY EIGHT OF THE FOLLOWING. 16M (8x2) 1 a) State any four ideal properties of buffer solution. ANY The pH of buffer solution remains constant. -

Influence of Bowel Preparation Before 18F-FDG PET/CT on Physiologic

Influence of Bowel Preparation Before 18F-FDG PET/CT on Physiologic 18F-FDG Activity in the Intestine Jan D. Soyka1, Klaus Strobel1, Patrick Veit-Haibach1, Niklaus G. Schaefer1, Daniel T. Schmid1, Alois Tschopp2, and Thomas F. Hany1 1Department of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland; and 2Department for Biostatistics, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Our objective was to investigate the use of bowel preparation be- mendations have been made in order to reduce physiologic fore 18F-FDG PET/CT to reduce intestinal 18F-FDG uptake. uptake of 18F-FDG in the intestine or to improve the ability Methods: Sixty-five patients with abdominal neoplasias were to evaluate intestinal structures (5–8). However, no published assigned either to a bowel-preparation group (n 5 26) or to a na- tive group (n 5 39). 18F-FDG activity was measured in the small study has proven that bowel preparation before PET/CT intestine and the colon. Results: In the 26 patients with bowel is beneficial. We therefore conducted a naturally randomized preparation, average maximal standardized uptake value (SUV- and single-blinded study to evaluate the effects of bowel max) was 3.5 in the small intestine and 4.4 in the colon. In the cleansing on intestinal 18F-FDGactivityinPET/CT. 39 patients without bowel preparation, average SUVmax was 2.6 in the small intestine and 2.7 in the colon. 18F-FDG activity im- MATERIALS AND METHODS paired diagnosis in 6 patients (23%) in the bowel-preparation group and 11 patients (28%) in the native group (P 5 0.5). SUV- This prospective, naturally randomized, and single-blinded max in the colon was significantly higher in the bowel-prepara- study was approved by our local ethics committee. -

Assessment Report on Cassia Senna L

European Medicines Agency Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use London, 27 April 2007 Doc. Ref. EMEA/HMPC/51868/2006 Corr. COMMITTEE ON HERBAL MEDICINAL PRODUCTS (HMPC) ASSESSMENT REPORT ON CASSIA SENNA L. AND CASSIA ANGUSTIFOLIA VAHL, FOLIUM Herbal substance Cassia senna L. (C. acutifolia Delile) [Alexandrian or Khartoum senna] or Cassia angustifolia Vahl [Tinnevelly senna], folium (senna leaf) or a mixture of the two species Herbal preparation dried leaflets, standardised; standardised herbal preparations thereof Pharmaceutical forms Herbal substance for oral preparation Rapporteur Dr C. Werner Assessor Dr B. Merz Superseded 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) 75 23 70 51 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.europa.eu ©EMEA 2007 Reproduction and/or distribution of this document is authorised for non commercial purposes only provided the EMEA is acknowledged TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 3 II. Clinical Pharmacology 3 II.1 Pharmacokinetics 3 II.1.1 Phytochemical characterisation 3 II.1.2 Absorption, metabolism and excretion 4 II.1.3 Progress of action 5 II.2 Pharmacodynamics 5 II.2.1 Mode of action 5 • Laxative effect 5 II.2.2 Interactions 7 III. Clinical Efficacy 7 III.1 Dosage 7 III.2 Clinical studies 8 III.2.1 Constipation 8 III.2.2 Irritable bowel syndrome 10 III.2.3 Bowel cleansing 11 III.3 Clinical studies in special populations 15 III.3.1 Use in children 15 III.3.2 Use during pregnancy and lactation 16 III.4 Traditional use 17 IV. -

WO 2017/066488 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date W O 2017/066488 A l 2 0 April 2017 (20.04.2017) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/485 (2006.01) A61P 25/04 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61K 31/5415 (2006.01) A61P 1/08 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, (21) International Application Number: DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US20 16/0569 10 HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, EST, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (22) International Filing Date: KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, 13 October 2016 (13.10.201 6) MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (25) Filing Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, (26) Publication Language: English TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 62/240,965 13 October 2015 (13. 10.2015) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 62/300,014 25 February 2016 (25.02.2016) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, (71) Applicant: CHARLESTON LABORATORIES, INC. -

E42 Appendix 1 (Part 1 of 2): Categorization of Medications

This single copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. For permission to reprint multiple copies or to order presentation-ready copies for distribution, contact CJHP at [email protected] Appendix 1 (Part 1 of 2): Categorization of medications. Class and Type of Medication Specific Drugs Psychotropic Antiparkinsonian Benztropine, carbidopa/levodopa, levodopa/benserazide, pramipexole, procyclidine Hypnotic Zopiclone Antipsychotic (typical or atypical) Risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, haloperidol, perphenazine, loxapine, clozapine, methotrimeprazine Antidepressant Sertraline, trazodone, mirtazapine, citalopram, escitalopram, duloxetine Benzodiazepine Lorazepam, clonazepam, oxazepam Anticonvulsant Pregabalin, levetiracetam, phenytoin, valproic acid, gabapentin, divalproex, topiramate Cholinesterase inhibitor Donepezil Anticholinergic Atropine CNS stimulant Methylphenidate Cardiovascular Diuretic Furosemide, metolazone, spironolactone, indapamide, acetazolamide, hydrochlorothiazide Antilipemic Rosuvastatin, atorvastatin Antihypertensive Amlodipine, diltiazem, hydralazine -Blocker Bisoprolol, metoprolol, carvedilol, propranolol ACE inhibitor Lisinopril, ramipril, enalapril, perindopril, fosinopril Angiotensin II receptor blocker Olmesartan, irbesartan, valsartan, candesartan Antianginal Nitroglycerin Hematologic Anticoagulant Enoxaparin, heparin, apixaban, rivaroxaban, warfarin Platelet inhibitor Acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel Anemia therapy Ferrous gluconate, ferrous fumarate Endocrine Hormone replacement Levothyroxine, -

Medical Supplement

MEDICAL SUPPLEMENT Name _______________________________________ Date ______________________________ Are you presently being treated for medical problems? ⃝ Yes ⃝ No If yes, for what problem and who is treating you?__________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________________________ When was your last physical examination?______________________________________________________________ Where and by whom?_________________________________________________________________________ List all medications you are currently taking, including over the counter and herbal/natural preparations: Medication Dosage Why do you take it? Who prescribes? 1 1000 Darrington Drive, Suite 204, Cary, North Carolina 27513 | (P) 919.338.5620 | (F) 919.336.4519 | [email protected] MEDICAL SUPPLEMENT Do you have any drug, food, or environmental allergies? __________________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Have you had any bad drug reactions? Please describe. __________________________________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Please list any surgeries: Date ___________________Surgery For ___________________________________________ Date ___________________Surgery For ___________________________________________ Date ___________________Surgery -

Melanosis Coli

DOI: 10.31662/jmaj.2021-0031 https://www.jmaj.jp/ Images Melanosis Coli Akira Kuriyama Key Words: melanosis, constipation, laxatives, anthraquinone A 75-year-old man with a 23-year history of poorly controlled Informed Consent type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with chronic constipation. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to Colonoscopy showed heavily pigmented mucosa, resembling publish this case report including the accompanying images. leopard skin, from the cecum through the ascending colon (Figure 1). The patient had been using senna glycoside for the References last 7 years, which supported a diagnosis of melanosis coli. A multicenter observational study with patients who had 1. Wang S, Wang Z, Peng L, et al. Gender, age, and concomitant undergone colonoscopy suggested that the prevalence of mela- diseases of melanosis coli in China: a multicenter study of 6,090 nosis coli is approximately 1.8% (1). Melanosis coli is associated cases. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4483. with the chronic use of laxatives, particularly those containing 2. Byers RJ, Marsh P, Parkinson D, et al. Melanosis coli is anthraquinones, such as senna, rhubarb, and cascara. It can associated with an increase in colonic epithelial apoptosis and develop within a few months of using anthraquinone-contain- not with laxative use. Histopathology. 1997;30(2):160-4. ing laxatives. Anthraquinones cause direct injury to and apop- 3. Biernacka-Wawrzonek D, Stepka M, Tomaszewska A, et al. tosis of the colonic epithelial cells, resulting in lipofuscin dep- Melanosis coli in patients with colon cancer. Przeglad osition in the macrophages of the lamina propria (2), which is gastroenterologiczny. -

National Master List of Drugs and Lab Reagents

ITEM NAME 1 CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 1A Positive inotropic drugs 1AA Digtalis glycoside 02-01-00001 Digoxin 62.5mcg Tablet 2539500 02-01-00002 Digitoxin 100mcg Tablet 2397000 02-01-00003 Digoxin 125 mcg Tablet 2622000 02-01-00004 Digoxin 250 mcg Tablet 44165500 02-01-00005 Digoxin 50mcg /ml PG Elixir 800000 02-01-00006 Digoxin 250 mcg/ml inj (2ml) Ampoule 800000 1AB PHOSPHODIESTERASE INHIBITORS 02-01-00007 Enoximone 5mg/1ml inj (20ml) Ampoule 800000 1B DIURETICS 02-01-00008 Amiloride Hcl 5mg + Hydrochlorthiazide 50mg Tablet 50000000 02-01-00009 Bumetanide 1 mg Tablet 1369000 02-01-00010 Chlorthalidone 50mg Tablet 6360500 02-01-00011 Ethacrynic acid 50mg as sodium salt inj (powder for reconstitution) Vial 800000 02-01-00012 Frusemide 20mg/2ml inj Ampoule 9437000 02-01-00013 Frusemide 10mg/ml,I.V.infusion inj (25ml) Ampoule 800000 02-01-00014 Frusemide 40mg Tablet 78372000 02-01-00015 Frusemide 500mg Scored Tablet 800000 02-01-00016 Frusemide 1mg/1ml Oral solution peadiatric Liquid 800000 02-01-00017 Frusemide 4mg/ml Oral Solution 800000 02-01-00018 Frusemide 8mg/ml oral Solution 800000 02-01-00019 Hydrochlorothiazide 25mg Tablet 3173000 02-01-00020 Hydrochlorothiazide 50mg Tablet 3033500 02-01-00021 Indapamide 2.5mg Tablet 800000 02-01-00022 Indapamide 1.5mg S/R Coated Tablet 800000 02-01-00023 Spironolactone 25mg Tablet 8426000 02-01-00024 Spironolactone 100mg Tablet 5829500 02-01-00025 Xipamide 20mg Tablet 800000 1C BETA-ADRENOCEPTER BLOCKING DRUGS 02-01-00026 Acebutolol 100mg Tablet 800000 02-01-00027 Acebutolol 200mg Tablet 800000 02-01-00028 Atenolol 100mg Tablet 120000000 02-01-00029 Atenolol 50mg Tablet or (scored tab) 48893000 02-01-00030 Atenolol 25mg Tablet 8628500 02-01-00031 Bisoprolol fumarate 5mg Scored Tablet 800000 02-01-00032 Bisoprolol fumarate 10mg Scored Tablet 800000 02-01-00033 Carvedilol 6.25mg Tablet 3279500 02-01-00034 Carvedilol 12.5mg Tablet 2228500 02-01-00035 Carvedilol 25mg Tablet 2650000 02-01-00036 Esmolol Hcl 10mg/ml I.V. -

A Case Report of Delirium Induced by Herbal Laxative Senna

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research DOI: https://doi.org/10.52403/ijhsr.20210636 Vol.11; Issue: 6; June 2021 Website: www.ijhsr.org Case Report ISSN: 2249-9571 A Case Report of Delirium Induced by Herbal Laxative Senna Nimitha K J1, Porimita Chutia2, Pooja Misal3, Bhupendra Singh4 1,2,3 Senior Resident, 4Additional Professor, Department of Geriatric Mental Health, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India Corresponding Author: Nimitha K J ABSTRACT Constipation is one major complaint in elderly population. It may be due to physiological and anatomical reasons of aging, but it can be also due chronic medical and mental illnesses and due to use of multiple medications. Constipation itself is a precipitating factor for delirium. Drugs used for constipation can also be the culprit. A 64-year-old female who had a history of hypertension and chronic constipation presented with symptoms of confused and altered behavior, decreased oral intake, decreased sleep. On history taking it was known that she was using Herbal medication containing senna glycoside and other compounds since 8-9months. On examination she had signs of dehydration, disoriented and attention was impaired. On investigation her serum sodium was 122.6 mmol/ and other investigations were within normal limits. She was diagnosed as a case of Delirium according to ICD-10 criteria. Her dehydration was corrected by giving intravenous fluids and serum sodium level was corrected using salt capsules 2 tablets thrice daily. For disturbed sleep she was prescribed Tab Melatonin 10mg at bedtime and constipation was treated with per rectal enema and syrup lactulose 30ml at bedtime. -

WO 2018/013871 Al 18 January 2018 (18.01.2018) W !P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2018/013871 Al 18 January 2018 (18.01.2018) W !P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: Published: A61K 31/715 (2006.01) A61P 43/00 (2006.01) — with international search report (Art. 21(3)) A61K 9/00 (2006.01) — before the expiration of the time limit for amending the (21) International Application Number: claims and to be republished in the event of receipt of PCT/US20 17/042022 amendments (Rule 48.2(h)) (22) International Filing Date: 13 July 2017 (13.07.2017) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Language: English (30) Priority Data: 62/361,998 13 July 2016 (13.07.2016) US (71) Applicant: KALEIDO BIOSCIENCES, INC. [US/US]; 47 Moulton St, Cambridge, MA 02138 (US). (72) Inventors: VON MALTZAHN, Geoffrey, A.; 42 Myrtle St Apt Bl, Somerville, MA 02145 (US). RUBENS, Ja¬ cob, Rosenblum; 177 Hancock St., Cambridge, MA 02139 (US). (74) Agent: COLLAZO, Diana, M. et al; Lando & Anastasi, LLP, Riverfront Office Park, One Main Street, Suite 1100, Cambridge, MA 02142 (US). (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Clozapine-Induced GI Hypomotility: from Constipation to Bowel Obstruction

Pearls Clozapine-induced GI hypomotility: From constipation to bowel obstruction Andrew Cruz, MD, and Oliver Freudenreich, MD Dr. Cruz is a PGY-2 resident, MGH/ Table McLean Adult Psychiatry Residency atients who are treated with clozap- Program, and Dr. Freudenreich ine—a second-generation antipsy- Bowel regimen for chronic is Co-Director, Schizophrenia chotic approved for treatment-resistant constipation Clinical and Research Program, P Massachusetts General Hospital, schizophrenia—require monitoring for seri- Stool softener (daily) Boston, Massachusetts. ous adverse effects. Many of these adverse Docusate sodium 100 mg twice daily Disclosures effects, such as agranulocytosis or seizures, Stimulant laxative (weekly and as needed) The authors report no financial relationships with any company are familiar to clinicians; however, gastro- Bisacodyl, 5 to 15 mg/d, as needed whose products are mentioned in intestinal (GI) hypomotility is not always Senna glycoside, 15 mg/d, as needed this article, or with manufacturers of competing products. recognized as a potentially serious adverse effect, even though it is one of the most common causes for hospital admission.1 Its Staff who care for patients taking clozapine manifestations range from being relatively who live in a supervised setting should be benign (nausea, vomiting, constipation) to educated about the relevance of a patient’s potentially severe (fecal impaction) or even changing bowel habits or GI complaints. life-threatening (bowel obstruction, ileus, Also, teach patients about simple lifestyle toxic megacolon).2 modifications they can make to counteract GI hypomotility is caused by clozapine’s constipation, including increased physical strong anticholinergic properties, which activity, adequate hydration, and consum- lead to slowed smooth muscle contrac- ing a fiber-rich diet. -

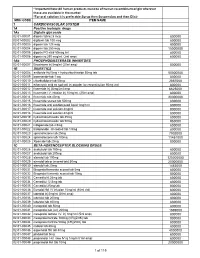

National Master List of Drugs and Lab Reagents

* Important Note:All human products must be of human recombinant origin wherever these are available in the market *For oral solution it is preferable:Syrup then Suspension and then Elixir MOH CODE ITEM NAME 1 CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 1A Positive inotropic drugs 1Aa Digtalis glycoside 02-01-00001 digoxin tab 62.5 mcg 800000 02-01-00002 digitoxin tab 100 mcg 800000 02-01-00003 digoxin tab 125 mcg 800000 02-01-00004 digoxin tab 250 mcg 15000000 02-01-00005 digoxin PG elixir 50mcg /ml 800000 02-01-00006 digoxin inj 250 mcg/ml, (2ml amp) 800000 1Ab PHOSPHODIESTERASE INHIBITORS 02-01-00007 Enoximone inj 5mg/ml (20ml amp) 800000 1B DIURETICS 02-01-00008 amiloride Hcl 5mg + hydrochlorthiazide 50mg tab 50000000 02-01-00009 bumetanide tab 1 mg 800000 02-01-00010 chlorthalidone tab 50mg 2867000 02-01-00011 ethacrynic acid as sod.salt inj powder for reconstitution 50mg vial 800000 02-01-00012 frusemide inj 20mg/2ml amp 6625000 02-01-00013 frusemide I.V. infusion inj 10mg/ml, (25ml amp) 800000 02-01-00014 frusemide tab 40mg 20000000 02-01-00015 frusemide scored tab 500mg 800000 02-01-00016 frusemide oral solution pead liquid 1mg/1ml 800000 02-01-00017 frusemide oral solution 4mg/ml 800000 02-01-00018 frusemide oral solution 8mg/ml 800000 02-01-00019 hydrochlorothiazide tab 25mg 800000 02-01-00020 hydrochlorothiazide tab 50mg 950000 02-01-00021 indapamide tab 2.5mg 800000 02-01-00022 Indapamide s/r coated tab 1.5mg 800000 02-01-00023 spironolactone tab 25mg 7902000 02-01-00024 spironolactone tab 100mg 11451000 02-01-00025 Xipamide tab 20mg 800000 1C