2020 Guidelines for Fire Blight Management in New York K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

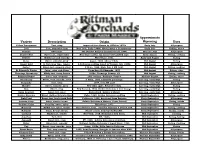

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Cedar-Apple Rust

DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION Agriculture and Natural Resources University of Arkansas System FSA7538 Cedar-Apple Rust Stephen Vann Introduction Assistant Professor One of the most spectacular Extension Urban Plant Pathologist diseases to appear in spring is cedar- apple rust. This disease is caused by the fungus Gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae and requires both cedar and apple trees to survive each year. It is mainly a problem in the eastern portion of North America and is most important on apple or crab Figure 2. Cedar-apple rust on crabapple apple (Malus sp), but can also affect foliage. quince and hawthorn. yellow-orange color (Figures 1 and 2). Symptoms On the upper leaf surface of these spots, the fungus produces specialized The chief damage by this disease fruiting bodies called spermagonia. On occurs on apple trees, causing early the lower leaf surface (and sometimes leaf drop and poor quality fruit. This on fruit), raised hair-like fruiting bod can be a significant problem to com ies called aecia (Figure 3) appear as mercial apple growers but also harms microscopic cup-shaped structures. the appearance of ornamental crab Wet, rainy weather conditions favor apples in the home landscape. On severe infection of the apple. The apple, symptoms first appear as fungus forms large galls on cedar trees small green-yellow leaf or fruit spots in the spring (see next section), but that gradually enlarge to become a these structures do not greatly harm Arkansas Is Our Campus Visit our web site at: Figure 1. Cedar-apple rust (leaf spot) on Figure 3. Aecia of cedar-apple rust on https://www.uaex.uada.edu apple (courtesy J. -

Handling of Apple Transport Techniques and Efficiency Vibration, Damage and Bruising Texture, Firmness and Quality

Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences PUBLISHED BY: B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACTIVITIES OF WP9 IN THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE AGROPHYSICS CONTRACT NO: QLAM-2001-00428 CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR APPLIED PHYSICS IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE WITH THE th ACRONYM AGROPHYSICS IS FOUNDED UNDER 5 EU FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH, TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES GENERAL SUPERVISOR OF THE CENTRE: PROF. DR. RYSZARD T. WALCZAK, MEMBER OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PROJECT COORDINATOR: DR. ENG. ANDRZEJ STĘPNIEWSKI WP9: PHYSICAL METHODS OF EVALUATION OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE QUALITY LEADER OF WP9: PROF. DR. ENG. BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI, JR. REVIEWED BY PROF. DR. ENG. JÓZEF KOWALCZUK TRANSLATED (EXCEPT CHAPTERS: 1, 2, 6-9) BY M.SC. TOMASZ BYLICA THE RESULTS OF STUDY PRESENTED IN THE MONOGRAPH ARE SUPPORTED BY: THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNDER GRANT NO. 5 P06F 012 19 AND ORDERED PROJECT NO. PBZ-51-02 RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF POMOLOGY AND FLORICULTURE B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ©Copyright by BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LUBLIN 2006 ISBN 83-89969-55-6 ST 1 EDITION - ISBN 83-89969-55-6 (IN ENGLISH) 180 COPIES, PRINTED SHEETS (16.8) PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER IN POLAND BY: ALF-GRAF, UL. -

Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains

United States Department of Agriculture Diseases of Trees in the Great Plains Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Service Research Station Report RMRS-GTR-335 November 2016 Bergdahl, Aaron D.; Hill, Alison, tech. coords. 2016. Diseases of trees in the Great Plains. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-335. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 229 p. Abstract Hosts, distribution, symptoms and signs, disease cycle, and management strategies are described for 84 hardwood and 32 conifer diseases in 56 chapters. Color illustrations are provided to aid in accurate diagnosis. A glossary of technical terms and indexes to hosts and pathogens also are included. Keywords: Tree diseases, forest pathology, Great Plains, forest and tree health, windbreaks. Cover photos by: James A. Walla (top left), Laurie J. Stepanek (top right), David Leatherman (middle left), Aaron D. Bergdahl (middle right), James T. Blodgett (bottom left) and Laurie J. Stepanek (bottom right). To learn more about RMRS publications or search our online titles: www.fs.fed.us/rm/publications www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/ Background This technical report provides a guide to assist arborists, landowners, woody plant pest management specialists, foresters, and plant pathologists in the diagnosis and control of tree diseases encountered in the Great Plains. It contains 56 chapters on tree diseases prepared by 27 authors, and emphasizes disease situations as observed in the 10 states of the Great Plains: Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming. The need for an updated tree disease guide for the Great Plains has been recog- nized for some time and an account of the history of this publication is provided here. -

Fruit Quarterly SPRING 2013 Leadership and Accountability

NEW YORK Editorial Fruit Quarterly SPRING 2013 Leadership and Accountability here are those who spend their hours discussing how to invest would not really harm their current operations but difficult and unfair the current times are. There are those would insure successful future ones. Twho reflect longingly about how wonderful and simple life used to be. There are also those who simply fail to see anything Today is always here and the future is always slightly out of positive until it is taken away from them. Then there are those your reach. The true mark of a leader is that they can function that we call “leaders” who are too busy looking forward to be within both. Like in years past we will and forever need to dragged down by all of this meaningless discussion. be investing in innovative research programs to improve our industry. There are those who may wish to have this I travel from west to east across New York and have done so accomplished entirely public funding. When you leave your all of my six decades. I am humbled by what I recall and what I future entirely to the fickle whims of the political world you currently see. The fruit industry has made enormous up- grades are not being “accountable” for the research programs you to its commercial farming practices in a very short period of desperately require for success in the years ahead. A shared time. Orchard acreage in New York State is down but our financial cash flow would be ideal. productivity and quality have never been at this high level. -

Progress in Apple Improvement

PROGRESS IN APPLE IMPROVEMENT J. R. MAGNESS, Principal Pomologisi, 13ivision of Fruit and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, liureau of Plant Industry ^ A HE apple we liave today is J^u" rciuovod from tlic "gift of the gods'' wliich prehistoric man found in roaming the woods of western Asia and temperate Europe. We can judge that apple only by the wild apples that grow today in the area between tlie Caspian Sea and Europe, which is believed to be the original habitat of the apple. These apples are generally onl>r 1 to 2 inches in diameter, are acici and astringent, and are far inferior io the choice modern horticultural varieties. The improvement of the apple through tlie selection of the best types of the wild seedlings goes far baclv to the very beginning of history. Methods of budding and grafting fiiiits were Icnown more than 2,000 years ago. According to linger, C^ato (third century, B. C.) knew seven different apple varieties, l^liny (first centiuy, A. D.) knew^ 36 different kinds. By tlie time the iirst settlers froni Europe were coming to the sliores of North America., himdreds of apple varieties had been named in European <M)unt]*ies, The superior varieties grown in l^^urope in the seventeenth century had, so far as is known, all developed as chance seedlings, but garden- ers had selected the best of the s(>edling trees îvnd propagated them vegetatively. The early American settlers, ptirticiilarly those from the temperate portions of Europe, who came to the eastern coast of North Amer- ica, brought with them seeds and in some cases grafted trees of European varieties. -

Managing Fire Blight by Choosing Decreased Host Susceptibility Levels and Rootstock Traits , 2020 , January 15 January

Managing Fire Blight by Choosing Decreased Host Susceptibility Levels and Rootstock Traits , 2020 , January 15 January Awais Khan Plant Pathology and Plant-microbe Biology, SIPS, Cornell University, Geneva, NY F ire blight bacterial infection of apple cells Khan et al. 2013 Host resistance and fire blight management in apple orchards Host resistance is considered most sustainable option for disease management due to Easy to deploy/implement in the orchards Low input and cost-effective Environment friendly No choice to the growers--most of the new and old cultivars are highly susceptible Apple breeding to develop resistant cultivars Domestication history of the cultivated apple 45-50 Malus species-----Malus sieversii—Gene flow Malus baccata Diameter: 1 cm Malus sieversii Malus baccata Diameter: up to 8 cm Malus orientalis Diameter: 2-4 cm Malus sylvestris Diameter: 1-3 cm Duan et al. 2017 Known sources of major/moderate resistance to fire blight to breed resistant cultivars Source Resistance level Malus Robusta 5 80% Malus Fusca 66% Malus Arnoldiana, Evereste, Malus floribunda 821 35-55% Fiesta, Enterprise 34-46% • Fruit quality is the main driver for success of an apple cultivar • Due to long juvenility of apples, it can take 20-25 years to breed resistance from wild crab apples Genetic disease resistance in world’s largest collection of apples Evaluation of fire blight resistance of accessions from US national apple collection o Grafted 5 replications: acquired bud-wood and rootstocks o Inoculated with Ea273 Erwinia amylovora strain -

Brightonwoods Orchard

Managing Diversity Jimmy Thelen Orchard Manager at Brightonwoods Orchard 2020 Practical Farmers of Iowa Presentation MAP ORCHARD PEOPLE ORCHARD PEOPLE • UW-Parkside Graduate • Started at Brightonwoods in 2006 • Orchard Manager and in charge of Cider House • Case Tractor Hobby & Old Abe's News ORCHARD HISTORY • Initial sales all from on the farm (1950- 2001) “Hobby Orchard” • Expansion into multiple cultivars (10 acres) • 1980's • Added refrigeration • Sales building constructed ORCHARD HISTORY • Retirement begets new horizons • (1997-2020) • Winery (2000-2003) additional 2 acres of trees for the winery and 30+ varieties of apples & pears ORCHARD HISTORY • Cider House (2006) with UV light treatment and contract pressing • Additional ½ acre of Honeycrisp ORCHARD HISTORY • Additional 3 acres mixed variety higher density planting ~600 trees per acre ORCHARD HISTORY • Addition of 1 acre of River Belle and Pazazz ORCHARD • Not a Pick- your-own • All prepicked and sorted • Not Agri- entertainment focused ACTIVITIES WHERE WE SELL • Retail Focused • At the Orchard • Summer / Fall Farmers' Markets • Winter Farmers' Markets • Restaurants • Special Events ADDITIONAL PRODUCTS • Honey, jams & jellies • Pumpkins & Gourds • Squash & Garlic • Organic vegetables on Sundays • Winery Products • Weekend snacks and lunches 200+ VARIETIES Hubardtson Nonesuch (October) Rambo (September) Americus Crab (July / August) Ida Red (October) Red Astrashan (July–August) Arkansas Black (October) Jersey Mac (July–August) Red Cortland(September) Ashmead's Kernal (October) -

THEIR PER.F@Rmflnce RT Genevfl WEWER APPLE VARIETIES - THEIR PERFORMANCE at GENEVA L

NEW€? APPLE VFlRETES THEIR PER.F@RmFlnCE RT GEnEVFl WEWER APPLE VARIETIES - THEIR PERFORMANCE AT GENEVA L. G. Klein and John Einset M. Y. S. Agricultural Experiment Station Geneva, N, Y. Revised January 1958 In New York State there has been a real need for improved varieties to replace some of the older varieties which are gradually disappearing from com- mercial plantings due to certain horticultural wealcnesses. Baldwin, Northern Spy, Ben Davis and King, at one time were very important varieties in Western New York but are no longer being planted in any quantity. These varieties all possess horticultural faults which precludes recommending them for modern plantinge. Baldwin, although a good processing variety, is not too winter hardy and has a strong tendency toward biennial bearing. Northern Spy and King, although both high quality varieties, are not sufficiently product- ive while Ben Davis has lost favor largely because of its low quality. In recent years there has been a tremendous tnterest in new apple varieties for New Yark State. Western New York growers have been particularly anxious to find a suitable replacement for Baldwin and Northern Spy, while Hudson Valley growers -have been on the lookout for McIntosh type apples which mature earlier or later than McIntosh, the dominating variety in the Midson Valley. In addition to needing new varieties as replacements for older ones, new varieties are also needed for various specific uses, such as the baby food and frozen slice industry. Early processing varieties are also needed to compete with southern grown apples (particularly the York Imperial) which are canned and shipped into New York State while most New York processing varieties are still on the trees,' Although we are always looking for still greater improvement, the variety situation in this State is much better than it was a few years ago. -

Tree Diseases

Tree Diseases In North Texas home owners cherish their trees for their beauty and for their shade protection from summer’s sun. Unfortunately, trees can experience problems that affect their attractive appearance and may even lead to death. Trees are vulnerable to environmental stress, infectious diseases, insects and human-caused damage. Correctly diagnosing the cause of a tree’s problem is the most important step in successful treatment. To determine if your tree has a disease, examine the whole tree not just the area showing symptoms suggests Iowa State University Extension Service (Diagnosing Tree Problems). Check leaves for holes or ragged edges, discoloration or deformities Look at the tree’s trunk for damage to the bark such as cracks or splits Consider previous activity that may have impacted the tree’s root system such as planting shrubs nearby or construction of a sidewalk or adding hardscape like a deck or patio The following diseases occur in Denton County. This is not all-inclusive, but Master Gardeners have seen all of these (with the exception of oak wilt). If you need help diagnosing a tree problem, send a picture of the entire tree and close-ups of the problem area(s) to the help desk at [email protected]. If it is a new tree, include a picture of the bottom of the trunk where it meets the soil. Include such information as: Age of the tree When the problem was noticed Sudden or gradual onset Presence of insects Anything else you believe is relevant Anthracnose This fungus is usually on lower branches, following a cool, wet, spring. -

Fire Blight of Apple and Pear

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Fire Blight of Apple and Pear Updated by Tianna DuPont, WSU Extension, February 2019. Original publication by Tim Smith, Washington State University Tree Fruit Extension Specialist Emeritus; David Granatstein, Washington State University; Ken Johnson, Professor of Plant Pathology Oregon State University. Overview Fire blight is an important disease affecting pear and apple. Infections commonly occur during bloom or on late blooms during the three weeks following petal fall. Increased acreage of highly susceptible apple varieties on highly susceptible rootstocks has increased the danger that infected blocks will suffer significant damage. In Washington there have been minor outbreaks annually since 1991 and serious damage in about 5-10 percent of orchards in 1993, 1997, 1998, 2005, Figure 2 Bloom symptoms 12 days after infection. Photo T. DuPont, WSU. 2009, 2012, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018. Shoot symptoms. Tips of shoots may wilt rapidly to form a Casual Organism “shepherd’s crook.” Leaves on diseased shoots often show blackening along the midrib and veins before becoming fully Fire blight is caused by Erwinia amylovora, a gram-negative, necrotic, and cling firmly to the host after death (a key rod-shaped bacterium. The bacterium grows by splitting its diagnostic feature.) Numerous diseased shoots give a tree a cells and this rate of division is regulated by temperature. Cell burnt, blighted appearance, hence the disease name. division is minimal below 50 F, and relatively slow at air temperatures between 50 to 70 F. At air temperatures above 70 F, the rate of cell division increases rapidly and is fastest at 80 F.