Case 1:04-Cv-03908-JBS-AMD Document 29 Filed 08/24/05 Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2020

State of New Jersey Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson ANNUAL REPORT 10/01/19 to 09/30/20 State of New Jersey OFFICE OF THE CORRECTIONS OMBUDSPERSON ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Introduction 3 Historical Perspective 5 Mission, Goals, and Objectives 6 Operating Procedures 7 Corrections Ombudsperson’s Staff 8 Accomplishments 8 Goal Assessment 9 General Information and Recommendations 10 Goals and Projects 21 Inmate Contacts Aggregated to Include All Facilities 23 Inmate Contacts Disaggregated by State Prison Facilities 25 Page 2 of 50 State of New Jersey OFFICE OF THE CORRECTIONS OMBUDSPERSON ANNUAL REPORT Introduction The Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson has successfully operated for forty-eight years. Throughout the year, staff continued to assist inmates, residents, attorneys, outside agencies, and the general public with matters relating to incarcerated offenders and committed sexually violent predators. The Department of Corrections (DOC) has an obligation to ensure that all persons committed to State Correctional Facilities and Residential Community Release Programs are provided with the custody, care, training, and treatment needed to prepare them for reintegration back into the community. Oversight by an independent body is essential to ensure the integrity of the system, administrative accountability, and to protect the rights of the incarcerated. The Corrections Ombudsperson’s role has a long and honorable tradition as a means of protecting against abuse, bias, and other improper treatment or unfairness. The Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson provides a concerned medium within which “State” sentenced inmates can seek redress for concerns that arise during incarceration regarding their living conditions, treatment, or any allegations of maladministration or inaction by correctional authorities. -

State of New Jersey Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson

State of New Jersey Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson ANNUAL REPORT 10/01/19 to 09/30/20 OFFICE OF THE CORRECTIONS OMBUDSPERSON ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Introduction 3 Historical Perspective 5 Mission, Goals, and Objectives 6 Operating Procedures 7 Corrections Ombudsperson’s Staff 8 Accomplishments 8 Goal Assessment 9 General Information and Recommendations 10 Goals and Projects 21 Inmate Contacts Aggregated to Include All Facilities 23 Inmate Contacts Disaggregated by State Prison Facilities 25 Page 2 of 50 OFFICE OF THE CORRECTIONS OMBUDSPERSON ANNUAL REPORT Introduction The Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson has successfully operated for forty-eight years. Throughout the year, staff continued to assist inmates, residents, attorneys, outside agencies, and the general public with matters relating to incarcerated offenders and committed sexually violent predators. The Department of Corrections (DOC) has an obligation to ensure that all persons committed to State Correctional Facilities and Residential Community Release Programs are provided with the custody, care, training, and treatment needed to prepare them for reintegration back into the community. Oversight by an independent body is essential to ensure the integrity of the system, administrative accountability, and to protect the rights of the incarcerated. The Corrections Ombudsperson’s role has a long and honorable tradition as a means of protecting against abuse, bias, and other improper treatment or unfairness. The Office of the Corrections Ombudsperson provides -

Corrections FY05

CORRECTIONS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS OVERVIEW The mission of the New Jersey Department of Corrections is to ensure Programs and Community Services that all persons committed to the State’s correctional institutions are The Division of Programs and Community Services offers an array confined with the level of custody necessary to protect the public, and of institutional and community--based programs for offenders, that they are provided with the care, discipline, training, and including community labor assistance, academic and vocational treatment needed to prepare them for reintegration into the educational programs, recreational programs, library (lending and community. law) services, and substance abuse treatment. The Division contracts with private and non--profit providers throughout the State to provide The Department’s goals and objectives are to: control costs and community--based residential treatment programs for offenders improve productivity and operational efficiency; expand treatment under community supervision. The fiscal 2005 appropriation and rehabilitation services; expand community programs and continues at $58.7 million, providing for 2,629 slots. reintegration services; improve academic and educational programs. State Parole Board The Department will accomplish these goals and objectives by: The State Parole Board’s mission is to promote the effective and maximizing the use of technology to improve service delivery and efficient assessment of inmates prior to parole, and the efficient costs; expanding inmate public service programs and outreach supervision of parolees after they have attained parole status. During efforts; evaluating and measuring program effectiveness; enhancing fiscal 2002, the Division of Parole Supervision within the emergency response capability; and expanding inmate work Department of Corrections was transferred to the State Parole Board programs. -

Testimonies of Torture in New Jersey Prisons

Testimonies of Torture in New Jersey Prisons EVIDENCE OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS A collection of testimonies from prisoners in New Jersey prisons, documenting uses of physical, chemical, and no-touch torture, among other human rights abuses. American Friends Service Committee Northeast Region Healing Justice Program Edited by: Bonnie Kerness Director, Prison Watch Program 89 Market Street, 6th floor Newark, NJ 07102 (973) 643-3192 Editorial Assistant Jessica Gonzalez Intern, Prison Watch Program Torture in New Jersey Prisons ǀ Evidence of Human Rights Violations February 2015 INTRODUCTION The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Quaker faith based organization that promotes lasting peace with justice, as a practical expression of faith in action. AFSC’s interest in prison reform is strongly influenced by Quaker (Religious Society of Friends) activism addressing prison conditions as informed by the imprisonment of Friends for their beliefs and actions in the 17th and 18th centuries. AFSC has spoken out on behalf of prisoners whose voices are all too frequently silenced. Drawing on continuing spiritual insights and working with people of many backgrounds, we nurture the seeds of change and respect for human life that transform social relations and systems. For over two decades, the Prison Watch Program of the American Friends Service Committee, located in Newark, NJ, has been collecting testimonies in the form of letters from prisoners across the United States. These letters document various human rights abuses in US prisons, including, but not limited to, physical, chemical, and no-touch torture at the local, state and federal levels. It is clear that the concepts of international human rights law need to find their way into the US law enforcement, judicial and prison systems. -

Bid Solicitation Appendix a 19Dpp00288 List and Facility Descriptions

BID SOLICITATION APPENDIX A 19DPP00288 LIST AND FACILITY DESCRIPTIONS New Jersey State Prison – Second & Cass Street, Trenton, NJ -The maximum-security prison, located in Trenton, provides programs for adult male offenders. Work opportunities are provided by five State Use Industries shops within the prison for the production of materials and products to be used by various State agencies and local governments. Educational opportunities are comprehensive, covering adult basic education through college and including a five-cluster vocational education program. An Administration Segregation Unit inside the prison is available for housing and programming designed to treat the more severe behavioral problems which occur in the prison system. Vroom Central Reception and Assignment Facility, Sullivan Way, Trenton, NJ-The Central Reception and Assignment Facility serves as a central processing unit for all adult male offenders sentenced to the New Jersey Department of Corrections. It is responsible for objectively classifying all State inmates, and providing all intake examinations/evaluations, including medical, dental, educational, psychological, etc. The Jones Farm Minimum Security Unit is a satellite unit. It serves as a work camp for inmates serving non-violent short-term sentences. The facility supports the Central Reception and Assignment Facility in the delivery of food services, building and grounds maintenance/repairs and other activities as needed. East Jersey State Prison , US Rt. 1 @ Rahway Avenue, Woodbridge, NJ-This prison provides maximum, medium, and minimum-security programs for male adult offenders. Work opportunities are provided by five State Use Industries shops. Food service, grounds maintenance, institutional maintenance and farm services are provided by inmates at the North Jersey Developmental Center, Totowa. -

State of New Jersey Department of Corrections

STATE OF NEW JERSEY DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS ANNUAL REPORT 2007 GEORGE W. HAYMAN COMMISSIONER MESSAGE FROM COMMISSIONER GEORGE W. HAYMAN We in the New Jersey De- positive im- partment of Corrections, un- pact not only der the leadership of Gover- in the lives of nor Jon S.Corzine, remain offenders, dedicated to solidifying our but in the stature among the most effi- communities cient law enforcement agen- in which we cies in the nation. Through live and the successful implementa- work. tion of a wide array of pro- grams and initiatives, we This report is continued to make strides designed to toward that goal in the 2007 provide in- calendar year. sight into a complex sys- The ever-evolving standards tem that of recruitment and training strives to are higher than ever before, meet the assuring that today’s correc- challenges of tion officer is the best pre- modern cor- pared and most professional rectional in the history of the Depart- management. ment of Corrections. Our In order to custody staff is the last line achieve our of defense our society has objectives, I against its most dangerous will continue to rely on what I rooms and libraries, thera- criminal offenders. Yet, the consider this department’s peutic communities and of- nature of an officer’s interac- most valuable resource – the fender reentry programming. tion with an inmate can NJDOC’s outstanding work- It is highly trained officers, prove to be the difference force, more than 9,000 strong, investigators, social workers between a perpetual life of which shares my vision of a and educators committed to crime and change for the bet- proactive law enforcement making difference, both in- ter. -

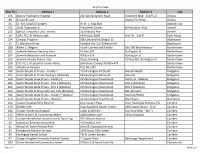

Ship to Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City 135 Ancora Psychiatric

Ship To Codes Ship To Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City 135 Ancora Psychiatric Hospital 202 Spring Garden Road Sycamore Bldg - 2nd Fl-2J Ancora 86 65 Laurel Lane Ancora Psy Hosp Ancora 65 Dr. M.L.King Ed Complex Dr M. L. King Blvd. Atlantic City 193 Adult Diagnostic & Treatment Center 8 Production Way Avenel 226 Special Treatment Unit - Annex 120 Rahway Ave Avenel 69 UMG-PCC At Hillsborough 649 Route 206N Unit 20 - 2nd Fl Belle Mead 234 Campus Program 508 Lakeland Rd (Bldg D-5) Blackwood 32 G. Woodard Gross Camden Cty. Col./Jefferson Hl. Blackwood 188 Albert C. Wagner Youth Correctional Facility Box 500 Ward Avenue Bordentown 202 Juvenile Medium Security Facil Po Box 307 Burlington St Bordentown 204 Juvenile Reception and Assessm PO Box 679 Burlington St Bordentown 205 Juvenile Female Secure Care Hayes Building PO Box 367, Burlington St Bordentown 236 D.O.V.E.S. Residential Comm Home Johnstone Campus PO Box 479 Bordentown 245 Johnstone Campus P.O. Box 307 Bordentown 186 South Woods St Prison - Facility 2 215 Burlington Rd South Mental Health Bridgeton 187 South Woods St Prison-Facility 1 (Medical) 215 Burlington Rd South Medical Bridgeton 260 South Woods State Prison - Facility 3 215 Burlington Road South Facility 3 - Medical Bridgeton 261 South Woods State Prison - ECU 1 (Medical) 215 Burlington Road South ECU 1 (Medical) Bridgeton 262 South Woods State Prison - ECU 2 (Medical) 215 Burlington Road South ECU 2 (Medical) Bridgeton 263 South Woods St Prison Min Sec Unit (Medical) 215 Burlington Road South Min Sec Unit Bridgeton 264 South Woods State Prison - Facility 2 Medical 215 Burlington Road South Facility2/Medic Bridgeton 259 South Woods State Prison - (Sharps) 215 Burlington Road South Mail Room Burlington 106 Cooper Hospital/Univ Med Ctr One Cooper Plaza Univ. -

Discussion Points

Department of Corrections and State Parole Board FY 2019-2020 Discussion Points DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS 1. P.L.2019, c.32 established several multiyear schedules for gradually raising the State minimum wage from currently $8.85 per hour to not less than $15.00 per hour. The increase may affect department staff, third parties that provide services to or on behalf of the department, and programs with means-tested eligibility criteria. In FY 2020, the general State minimum wage will rise as follows: 1) on July 1, 2019 to $10.00 per hour; and 2) on January 1, 2020, to not less than $11.00 per hour. The general minimum wage schedule will increase to at least $12 per hour on January 1, 2021; $13 per hour on January 1, 2022; $14 per hour on January 1, 2023; and $15 per hour on January 1, 2024. Questions: Please quantify the fiscal impact to the Department of Corrections (DOC) in FY 2020 of the increases in the minimum wage of department employees from $8.85 to $10 per hour on July 1, 2019 and from $10 to $11 per hour on January 1, 2020, and the number of employees who will be impacted by each increase. No current DOC staff would be impacted by raising the minimum wage. Relative to current compensation levels, please provide the same information assuming an hourly minimum wage of $12, $13, $14, and $15. No current DOC staff would be impacted by raising the minimum wage. Please quantify the fiscal impact to the department in FY 2020 of the increases in the minimum wage of persons in the custody of the department, under the supervision of the department, and employees of third parties that provide services either to the department, including temporary employment services, or on behalf of the department according to contractual agreements. -

2014 ANNUAL REPORT November 16, 2015 with Governor Corrections

2 Message from Commissioner Gary M. Lanigan 4 Taking a Look Back on 2014 5 Mission Statement 8 Office of the Commissioner 9 Office of Legal & Regulatory Affairs 9 Office of Public Information 13 Office of the Chief of Staff 14 Fleet Management Unit 14 Office of Human Resources 15 Office of Training 16 Office of Policy and Planning 17 Division of Administration 20 Office of Financial Management 20 Office of Information Technology 22 Bureau of State Use Industries 23 Division of Operations 24 AgriIndustries 24 Capital Planning and Construction Unit 24 Central Medical/Transportation Unit 25 Central Operations Desk (COD) 27 Classification Support & Training/Auditing Units 28 Field Services Unit 29 Health Services Unit 30 Immigration Services, Parole Monitoring and 33 Office of Interstate Services Release Notification Unit – Central Office 34 Special Operations Group 34 Division of Programs and Community Services 40 Office of the Assistant Commissioner 40 Office of Community Programs and Outreach Services 42 Office of Educational Services 45 Office of Transitional Services 47 3 Message from Commissioner Gary M. Lanigan The New Jersey Department of Corrections has long been considered among the most efficient law enforcement agencies in the nation. Through the implementation of a wide array of initiatives, once again, we strengthened our reputation in 2014. We proudly heed Governor Chris Christie’s call to find innovative ways to deliver services and enhance public safety as effectively and efficiently as possible. Our successes can be attributed to diligent planning, forward thinking and the utilization of programs and services that enable inmates to acquire and develop the necessary skills to ultimately become productive, law-abiding members of their communities. -

REENTRY COALITION of NEW JERSEY Reentry Coalition of New Jersey

REENTRY COALITION OF NEW JERSEY Reentry Coalition of New Jersey IMPACT OF COMMUNITY CORRECTIONS IN NEW JERSEY REDUCING PRISON POPULATION, INCARCERATION COSTS & RECIDIVISM Date: 12/20/2017 Kevin McHugh, Executive Director REENTRY COALITION OF NEW JERSEY IMPACT OF COMMUNITY CORRECTIONS IN NEW JERSEY: REDUCING PRISON POPULTION, INCARCERATION COSTS & RECIDIVISM INTRODUCTION NEW JERSEY PRISON SYSTEM IN CRISIS Over the past two decades, community 1980 – 1999 corrections programs have played a vital role in reducing the prison population and the New Jersey’s the prison population grew by 359 percent from 1980 to 1999 increasing costs of incarceration in New Jersey. At the same time, they have contributed to a from less than 7,000 inmates to its peak of marked improvement in public safety as 31,493 inmates in 1999. The rapid growth of evidenced by significant reductions in New Jersey’s prison population was accom- offender recidivism rates and dramatically panied by a corresponding explosion in state lower crime rates. This report chronicles the spending on corrections. During this same evolution of New Jersey’s community-based period NJ Corrections budget grew from programs from a response to prison $92.3 million to $845.7 million.¹ overcrowding to a highly successful and cost effective prisoner re-entry and public safety Reflecting a national trend, New Jersey’s pris- strategy. on population growth was fueled by the ‘get tough on crime’ philosophy and the institu- tion of mandatory minimum sentences for select crimes, including violent and drug crimes. *Data retrieved from US Bureau of Justice Statistics ¹ Manual for the Operation of Adult Drug Courts in New Jersey, July 22, 2002 Page 2 REENTRY COALITION OF NEW JERSEY IMPACT OF COMMUNITY CORRECTIONS IN NEW JERSEY: REDUCING PRISON POPULATION, INCARCERATION COSTS & RECIDIVISM Major changes in New Jersey’s sentencing laws that contributed to prison population growth included: 1981, Graves Act required a mandatory minimum sentence for offenses committed with a firearm. -

Corrections and Re-Entry

CORRECTIONS AND RE-ENTRY Scope of the Problem and Indicators of Need The New Jersey prison population has increased over the last two decades. Reasons for the increase include an increasing number of arrests due to drug offenses and greater use of mandatory minimum sentences. Parole failures, due to technical violations or new crimes are another reason for the population increase. In 2002, 40% of admissions to state prison were people who had failed on parole. 1 Between 1980 and 2002, New Jersey’s prison population increased from a rate of 76 to 331 per 100,000 residents. 2 An estimated 95% - 97% of inmates will return to New Jersey communities after their incarceration periods have been completed. 3 Many will return with substance abuse problems and health conditions that have not been addressed adequately during incarceration. Educational levels and stigma attached to a criminal record may add to difficulty reintegrating after release. In New Jersey, there have been approximately 14,000 state prison releases per year and 14,000 admissions per year since 2001. 4 The New Jersey Institute for Social Justice estimates that 70,000 people will be released from state prison over the next 5 years. Additional releases will come from jails. In 2002, nearly all (95%) of individuals incarcerated in New Jersey remained in New Jersey after release. Nearly one-third (31%) returned to Essex or Camden county. 5 State data reveals that, within three years of release from New Jersey state prisons, 53% of offenders are rearrested, 41% are reconvicted, 35% are re-incarcerated and 26% return to state prison.6 Education, skills and time out of the labor force affect employment after release. -

Provider Name Street Shp Street2 Shp City Shp Zipcode Shp

provider_name street_shp street2_shp city_shp zipcode_shp vax_manufacturer county Amb-fqhc Adult Clinic 1401 Atlantic Ave Suite 2800 Atlantic City 08401 Moderna Tx Atlantic Ancora Psychiatric Hospital Camden 301 Spring Garden Road Storeroom Ancora 08037 Moderna Tx Atlantic Atlantic County Health Department A 201 Shore Rd 1st Floor Clinic Northfield 08225 Moderna Tx Atlantic Atlanticare Regional Medical Center 1925 Pacific Avenue Atlantic City 08401 Pfizer Atlantic Medilink Rxcare Hammonton 44 South White Horse Pike Hammonton Town 08037 Moderna Tx Atlantic Sam's Club #8144 1025 Black Horse Pike Pleasantville 08232 Moderna Tx Atlantic Shoprite Pharmacy #612 23 Bethel Road Somers Point 08244 Moderna Tx Atlantic Shoprite Pharmacy #633 616 White Horse Pike Absecon 08201 Moderna Tx Atlantic Shore Memorial Center 100 Medical Center Way Somers Point 08244 Pfizer Atlantic Shore Physicians Group - Northfield 2605 Shore Rd Northfield 08225 Moderna Tx Atlantic Southern Jersey Family Medical Cent 1301 Atlantic Ave Atlantic City 08401 Moderna Tx Atlantic Southern Jersey Family Medical Cent 3003 English Creek Ave Ste C6 Egg Harbor Township08234 Moderna Tx Atlantic Southern Jersey Family Medical Cent 860 S White Horse Pike Hammonton 08037 Moderna Tx Atlantic Bergen New Bridge Medical Center 230 East Ridgewood Ave Paramus 07652 Moderna Tx Bergen Bergen New Bridge Medical Center 230 East Ridgewood Ave Paramus 07652 Pfizer Bergen Bergenfield Health Department 198 N Washington Ave Bergenfield 07621 Moderna Tx Bergen Englewood Hospital And Medical Cent 350