Disability Arts and Visually Impaired Musicians in the Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 189.Pmd

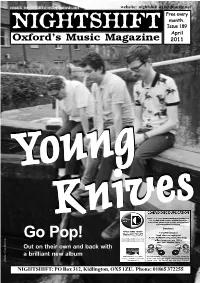

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

Mongrel Media

Mongrel Media PRESENTS A film by Mark Dornford-May Running Time: 126 Minutes Distribution 1028 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith, Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html U-CARMEN EKHAYELITSHA by Mark Dornford-May South Africa 2005, Super 16 / 35mm, Colour, 9 reels, Dolby Digital, Xhosa http://www.u-carmen.com Credits: Director Mark Dornford-May Producers Ross Garland, Mark Dornford-May, Camilla Driver Associate Producer Tanya Wagner Executive Producer Ross Garland Production Company Spier Films Screenplay Mark Dornford-May, Pauline Malefane, Andiswa Kedama Cinematography Giullio Biccari Art Director Craig Smith Choreography Joel Mthethwa Music Charles Hazlewood Editor Ronelle Loots Sound Barry Donnelly Costumes Jessica Dornford-May Cast: Pauline Malefane (Carmen), Andries Mbali (Bra Nkomo), Andiswa Kedama (Amanda), Ruby Mthethwa (Pinki), Andile Tshoni (Jongikhaya), Bulelwa Cosa (Madisa), Zintle Mgole (Faniswa), Lungelwa Blou (Nomakhaya), Zamile Gantana (Captain Gantana), Zorro Sidloyi (Lalamile Nkomo), Joel Mthethwa (Songoma), Noluthando Boqwana (Manelisa) Short Synopsis: U-Carmen eKhayelitsha, a feature film sung and spoken in Xhosa. Based on Bizet's opera Carmen, the film is set in present day Khayelitsha. The link between the original opera and the screenplay is the acclaimed Dimpho Di Kopane cast and Bizet's sensational score. Synopsis: Carmen in Khayelitsha is a feature film based on Bizet’s nineteenth century opera but filmed on location in a modern South African setting. -

The Secret Speech of Lirnyky and Kobzari Encoding a Life Style Andrij Hornjatkevyč, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta

32 The Secret Speech of Lirnyky and Kobzari Encoding a Life Style Andrij Hornjatkevyč, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta In Ukraine, minstrels have been part of the folk tradition for centuries. There were two types of minstrels: kobzari who played a stringed musical instrument called the kobza, later to develop into the bandura, and lirnyky, who played the crank-driven hurdy-gurdy called the lira. These minstrels were traveling musicians – and much more besides. They were major sources of historical and religious information and, interestingly, most of them were blind. This infirmity made them dependent upon others for their livelihood, but they were not beggars. On the contrary, they were well-respected by the general populace. As with other professional groups, they belonged to guilds and new members, young children, went through an extensive apprenticeship period. Minstrels also spoke using a secret language called lebiis’ka mova, henceforth the Lebian language (argot) or Lebian. It should be pointed out immediately that this was not a full-fledged language with a distinct phonetic, lexical, morphological, and syntactic system. On the contrary, its underlying structure was that of contemporary Ukrainian, but crucial standard Ukrainian lexemes – nouns, pronouns, adjectives, numerals and verbs – were replaced by others. To an outsider, i.e., one not initiated into the guild, who might chance to hear a conversation in this argot, it might sound like Ukrainian, but, except for such ancillary parts of speech such as conjunctions, prepositions, interjections and particles – words that carry only relational information – it would be entirely unintelligible. This was reinforced by the fact that Lebian lexemes would be inflected – declined or conjugated – exactly as analogous Ukrainian words would be. -

Disability and Music

th nd 19 November to 22 December UKDHM 2018 will focus on Disability and Music. We want to explore the links between the experience of disablement in a world where the barriers faced by people with impairments can be overwhelming. Yet the creative impulse, urge for self expression and the need to connect to our fellow human beings often ‘trumps’ the oppression we as disabled people have faced, do face and will face in the future. Each culture and sub-culture creates identity and defines itself by its music. ‘Music is the language of the soul. To express ourselves we have to be vibrating, radiating human beings!’ Alasdair Fraser. Born in Salford in 1952, polio survivor Alan Holdsworth goes by the stage name ‘Johnny Crescendo’. His music addresses civil rights, disability pride and social injustices, making him a crucial voice of the movement and one of the best-loved performers on the disability arts circuit. In 1990 and 1992, Alan co- organised Block Telethon, a high-profile media and community campaign which culminated in the demise of the televised fundraiser. His albums included Easy Money, Pride and Not Dead Yet, all of which celebrate disabled identity and critique disabling barriers and attitudes. He is best known for his song Choices and Rights, which became the anthem for the disabled people’s movement in Britain in the late 1980s and includes the powerful lyrics: Choices and Right That’s what we gotta fight for Choices and rights in our lives I don’t want your benefit I want dignity from where I sit I want choices and rights in our lives I don’t want you to speak for me I got my own autonomy I want choices and rights in our lives https://youtu.be/yU8344cQy5g?t=14 The polio virus attacked the nerves. -

The Inner Vision Orchestra UK Tour Autumn 2014 the Tour Will Be Featured in a Full Length Documentary Being Made for National TV

BALUJI SHRIVASTAV PRESENTS The Inner Vision Orchestra UK Tour Autumn 2014 The tour will be featured in a full length documentary being made for National TV Photo by Simon Richardson INDIAN MAESTRO BALUJI SHRIVASTAV BRINGS MUSICIANS FROM AROUND THE WORLD WHO ARE BLIND OR PARTIALLY SIGHTED. “…An extraordinary musician.” – Charles Hazelwood, Songlines Magazine “Audience left the auditorium spellbound and humbled.” – Runi Khan, Songlines Magazine “Yes, Inner Vision have a sense of humour.” – Richard Brookes, Sunday Times ”The love I had for colour has been transferred to music.“ – Victoria Oruwari, The Guardian ABOUT THE INNER VISION ORCHESTRA Back by popular demand Inner Vision Orchestra celebrates the success of performing alongside Coldplay at the London 2012 Paralympic Closing Ceremony, and their sell-out UK tour of 2013. Indian maestro and Musical Director Baluji Shrivastav, has brought together incredible musicians from around the world who are blind or partially sighted. Their uplifting music moves between songs from Iran, Lebanon, Afghanistan, India, Nigeria, to soulful Gospel and Blues to sublime Indian Ragas and Western Classical compositions. Driven by the intensity of an inner vision they celebrate the power of music to transform lives. Baluji says: “Each member of the Inner Vision orchestra has a story to tell about the power of music. This is a story about music changing the lives of people. It is about amazing people using music to give their lives direction and purpose.” ABOUT BALUJI SHRIVASTAV Baluji Shrivastav has performed and taught all over the world and has recorded many albums with a wide variety of artists and bands such as Stevie Wonder, Massive Attack, Annie Lennox , Madness, Andy Sheppard, Guy Barker and Shakira. -

An Ethnomusicology of Disability Alex Lubet, Ph.D. School of Music University of Minnesota

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Tunes of Impairment: An Ethnomusicology of Disability Alex Lubet, Ph.D. School of Music University of Minnesota Abstract: "Tunes of Impairment: An Ethnomusicology of Disability" contemplates the theory and methodology of disability studies in music, a sub-field currently in only its earliest phase of development. The article employs as its test case the field of Western art ("classical") music and examines the reasons for the near total exclusion from training and participation in music performance and composition by people with disabilities. Among the issues around which the case is built are left-handedness as a disability; gender construction in classical music and its interface with disability; canon formation, the classical notion of artistic perfection and its analogy to the flawless (unimpaired) body; and technological and organizational accommodations in music-making present and future. Key words: music; disability; classical Introduction: The Social Model of Disability Current scholarship in Disability Studies (DS) and disability rights activism both subscribe to the social modeli that defines disability as a construct correlated to biological impairment in a manner analogous to the relationship between gender and sex in feminist theory.ii Disability is thus a largely oppressive practice that cultures visit upon persons with, or regarded as having, functional impairments. While social constructs of femininity may not always be oppressive, the inherent negative implications of 'dis-ability' automatically imply oppression or at least dis-advantage. Like constructions of gender, categorizations of disability are fluid; variable between and within cultures. -

In Search of Blind Blake Arthur Blake’S Death Certificate Unearthed by Alex Van Der Tuuk, Bob Eagle, Rob Ford, Eric Leblanc and Angela Mack

In Search of Blind Blake Arthur Blake’s death certificate unearthed By Alex van der Tuuk, Bob Eagle, Rob Ford, Eric LeBlanc and Angela Mack t is interesting to observe that the almost completed the manuscript. A framed copy of the toughest nuts to crack, but did not seem of the envisioned cover of the book hangs in his impossible. Lemon Jefferson’s death certificate New York Recording Laboratories record room. Hopefully such an important work did turn up as late as 2009 when it was found recorded and issued a relatively will see the light of day in the near future. listed under a different Christian name, notably Ilarge group of blind musicians for Blind Arthur Blake, Blind Willie Davis and Blind supplied by his landlady. their ‘race’ series, the Paramount Joe Taggart have been the ultimate frustration for researchers. Especially Blind Blake, for whom not Night And Day Blues 12000 and 13000 series. One would a shred of official documentation has been found By the early 1990s a new, important instrument only have to think of blues artists that he ever walked on this planet, aside from a for researchers was starting to develop: the like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind handful of accounts collected from people who Internet. Researchers were already integrating saw him play or played with him. Arthur Blake, Blind Willie Davis, official documents into their publications, like We only have an occasional report in the census reports from the Federal Census Bureau, Blind Roosevelt Graves and Blind Chicago Defender and the legacy of his Paramount as well as information found on birth and death Joel Taggart to name some of the recordings. -

The Inner Vision Orchestra UK Tour July – October 2014 the Tour Will Be Featured in a Full Length Documentary Being Made for National TV

BALUJI SHRIVASTAV PRESENTS The Inner Vision Orchestra UK Tour July – October 2014 The tour will be featured in a full length documentary being made for National TV Photo by Simon Richardson INDIAN MAESTRO BALUJI SHRIVASTAV BRINGS MUSICIANS FROM AROUND THE WORLD WHO ARE BLIND OR PARTIALLY SIGHTED. “…An extraordinary musician.” – Charles Hazelwood, Songlines Magazine “Audience left the auditorium spellbound and humbled.” – Runi Khan, Songlines Magazine “Yes, Inner Vision have a sense of humour.” – Richard Brookes, Sunday Times ”The love I had for colour has been transferred to music.“ – Victoria Oruwari, The Guardian ABOUT THE INNER VISION ORCHESTRA Back by popular demand Inner Vision Orchestra celebrates the success of performing alongside Coldplay at the London 2012 Paralympic Closing Ceremony, and their sell-out UK tour of 2013. Indian maestro and Musical Director Baluji Shrivastav, has brought together incredible musicians from around the world who are blind or partially sighted. Their uplifting music moves between songs from Iran, Lebanon, Afghanistan, India, Nigeria, to soulful Gospel and Blues to sublime Indian Ragas and Western Classical compositions. Driven by the intensity of an inner vision they celebrate the power of music to transform lives. Baluji says: “Each member of the Inner Vision orchestra has a story to tell about the power of music. This is a story about music changing the lives of people. It is about amazing people using music to give their lives direction and purpose.” ABOUT BALUJI SHRIVASTAV Baluji Shrivastav has performed and taught all over the world and has recorded many albums with a wide variety of artists and bands such as Stevie Wonder, Massive Attack, Annie Lennox , Madness, Andy Sheppard, Guy Barker and Shakira. -

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

Orchestra in a Field

ORCHESTRA IN A FIELD Date 2012 Region South West Artform Music Audience numbers 3,461 Annabel Jackson Associates Ltd role We evaluated Orchestra in a Field Methodology Online audience survey Background Orchestra in a Field was a two-day classical music festival at Glastonbury Abbey in Somerset developed and hosted by British conductor, Charles Hazlewood. The festival was piloted in 2009 and then held on 30th June and 1st July 2012. Description The festival was a joyful mix of classical and contemporary music, talks and live performances, camping and children's entertainment. Performers included Adrian Utley (Portishead) and Will Gregory (Goldfrapp) the Scrapheap Orchestra, the British Paraorchestra, Prof Green and Labrinth, with a fully staged performance of Carmen by a cast of professionals and local choirs. There were 2,636 adults audience members and 825 children (who were free), plus 160 professional artists and 780 other performers. Audience views There was a good balance between people attending as part of a family group, with friends, in a couple, and some on their own. Audience members were attracted by the mix of music, the link to Charles Hazlewood, the insight into performance from live rehearsals, the reasonable cost, the informality and the novelty. Flying Seagulls parade, Oil Photograph by Shoshana More than 80% of 160 respondents said that Orchestra in a Field was probably or definitely memorable, welcoming, enjoyable, relevant to them and inspiring. 94% of respondents said that Orchestra in a Field was special/different ________________________________________________________________________ ©Annabel Jackson Associates Ltd October 2012 from other music events. All of the respondents said it was a good idea to have a festival to bring classical music to more people. -

Charles Hazlewood - Brief Biography

Charles Hazlewood - Brief Biography “What Heston Blumenthal is to food, Charles Hazlewood is to music.” The Guardian Charles Hazlewood, British conductor, is a passionate advocate for a wider audience for orchestral music. After winning the European Broadcasting Union conducting competition in his 20’s, he has enjoyed a global and pioneering career conducting some of the world’s greatest orchestras including the Swedish Radio Symphony, Gothenburg & Malmö Symphonies, Copenhagen Philharmonic, the Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Concertgebouw of Amsterdam and the Philharmonia (London). Hazlewood is known for breaking new ground. By re-inventing the presentation of orchestral music and by collaborating with many ‘stars’ from across the genres of music Hazlewood has sought to embed the ‘magical instrument of the orchestra’ in 21st century music scene; but always with the same goal: to expose the deep, always-modern joy of orchestral music to a new audience. Hazlewood has conducted over 200 world premieres of new scores by contemporary composers, and worked with contemporary musicians as diverse as Wyclef Jean, Professor Green, Goldie, Nigel Kennedy and Steve Reich. He is the first conductor to headline with an orchestra at the Glastonbury International Festival of Contemporary Arts, the greatest rock festival in the world. Hazlewood's work as a composer and music director has been received with consistent critical acclaim. His South African township 'Carmen' film sung in Xhosa won the Golden Bear for Best Film at the Berlin Film Festival, his South African musical version of the mediaeval plays 'The Mysteries' was a sell out in London's West End and provoked the first leader on music theatre in the Times in 40 years; his re-invention (with Carl Grose) of John Gay's, the Beggar's Opera (Dead Dog in a Suitcase and Other Love Songs), was selected by the Guardian for its top 10 shows of 2015. -

The Passion of Joan of Arc with Adrian Utley, Will Gregory and Charles Hazlewood Supported by Hauser & Wirth Somerset

HAUSER & WIRTH Press Release The Passion of Joan of Arc With Adrian Utley, Will Gregory and Charles Hazlewood Supported by Hauser & Wirth Somerset Wells Cathedral, Somerset, England Friday 7 October 2016, 8 pm Hauser & Wirth Somerset, in collaboration with Adrian Utley (Portishead), Will Gregory (Goldfrapp) and award- winning conductor Charles Hazlewood, presents a special live orchestral performance and film screening in the magnificent medieval setting of Wells Cathedral. Adrian Utley and Will Gregory have devised a new score sound-tracking the dramatic and moving narrative of Danish film director Carl Theodor Dreyer’s ‘The Passion of Joan of Arc’ (1928), which chronicles Joan of Arc’s trial and execution during her captivity in France. Initially commissioned by the Colston Hall and supported by The Watershed, Bristol, the inventive new score will be performed live alongside a screening of the film, led by Charles Hazlewood with members of the Monteverdi Choir, percussion, horns, harp and synthesizers. Wells Cathedral is located at the heart of England’s smallest city, Wells in Somerset, situated 13 miles from Hauser & Wirth Somerset. Cited as one of the earliest English cathedrals to be constructed in Gothic style, the building is a treasured and significant architectural landmark in the south west of England. The distinguished setting will provide a unique opportunity to witness Hazlewood, Utley and Gregory’s breathtaking and inspired production. Located on the outskirts of Bruton, Hauser & Wirth Somerset is an innovative world-class gallery and arts centre that works in partnership with many local institutions, businesses and organisations to foster local creative talent and champion charities related to art, community, conservation and education.