Bill Crawford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRAFFIC Bulletin Volume 32, No. 2 (October 2020) (3.6 MB Pdf)

VOL. 32 NO. 2 32 NO. VOL. TRAFFIC 2 BULLETIN ONLINE TRADE IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN AMPHIBIANS BIRD SINGING COMPETITIONS UNDER COVID CONSUMER AWARENESS IN MYANMAR EVALUATING MARKET INTERVENTIONS TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. For further information contact: The Executive Director TRAFFIC David Attenborough Building Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK Telephone: (44) (0) 1223 277427 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.traffic.org With thanks to The Rufford Foundation for contributimg to the production costs of the TRAFFIC Bulletin is a strategic alliance of OCTOBER 2020 OCTOBER The journal of TRAFFIC disseminates information on the trade in wild animal and plant resources GLOBAL TRAFFIC was established TRAFFIC International David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge, CB2 3QZ, UK. in 1976 to perform what Tel: (44) 1223 277427; E-mail: [email protected] AFRICA remains a unique role as a Central Africa Office c/o IUCN, Regional Office for Central Africa, global specialist, leading and PO Box 5506, Yaoundé, Cameroon. Tel: (237) 2206 7409; Fax: (237) 2221 6497; E-mail: [email protected] supporting efforts to identify Southern Africa Office c/o IUCN ESARO, 1st floor, Block E Hatfield Gardens, 333 Grosvenor Street, and address conservation P.O. Box 11536, Hatfield, Pretoria, 0028, South Africa Tel: (27) 12 342 8304/5; Fax: (27) 12 342 8289; E-mail: [email protected] challenges and solutions East Africa Office c/o WWF TCO, Plot 252 Kiko Street, Mikocheni, PO Box 105985, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. -

INDIANA HORSE RACING COMMISSION 2021 Standardbred Mare Registrations Foals of 2022

INDIANA HORSE RACING COMMISSION 2021 Standardbred Mare Registrations Foals of 2022 Registration Horse Name Sire Dam Year 2021 A Cool Million Keystone Nordic Primrose Hanover 2021 A Plus American Ideal Has An Attitude 2021 A Real Doozie Sportsmaster Hillary 2021 Above All Hanover Donerail Astro Action 2021 Ajessia Jailhouse Jesse Atia 2021 Alibi Seelster Shadow Play Alias Seelster 2021 All About The Pace Roll With Joe Queen Of Blues 2021 Allspeedallthetime All Speed Hanover Glitter N Glitz 2021 Alyvia Deo Trixton Blue Yonder 2021 Amazing Arya Rockin Image Honey's Luck 2021 American Image Rockin Image L Dees Lourdes 2021 Angel From Above Bettor's Delight Jett Away 2021 Angel's Touch Always A Virgin Perfect Touch 2021 Anna D Ponder Cotton Candy 2021 Annie's Delight Bettor's Delight Ideal Weather 2021 Ariel Fashion Donato Hanover On The Glide 2021 Art Critic Art Major Snippet Hanover 2021 Artful Impulse Artistic Fella Art Debut June 25, 2021 2:23 PM Total Count: 288 Page 1 of 17 INDIANA HORSE RACING COMMISSION 2021 Standardbred Mare Registrations Foals of 2022 Registration Horse Name Sire Dam Year 2021 Artiawitchtoyou Art Major Serenity Hanover 2021 Arts Jem Art Official Midnight Jewel 2021 Artsy Princess Western Hanover Clouding Over 2021 Ashlake Angus Hall Candidcamerakosmos 2021 Ashok Ace Panspacificflight Shadow Baby 2021 Ava Destruction Artiscape Bust Out The Bid 2021 Bad Babysitter Manofmanymissions My Baby's Momma 2021 Balinska Hanover Somebeachsomewhere Brissonte Hanover 2021 Bamby's Beauty Art'S Conquest Falcon's Bamby 2021 Banderosa -

{PDF} Dark Avengers: End Is the Beginning Ebook Free Download

DARK AVENGERS: END IS THE BEGINNING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jeff Parker,Declan Shalvey,Kev Walker | 192 pages | 12 Feb 2013 | Marvel Comics | 9780785161721 | English | New York, United States Dark Avengers: The End Is the Beginning by Jeff Parker If I had, I might feel differently about it. Mar 14, Holden Attradies rated it liked it Shelves: fiction , sequential-art , super-heroes. At times I love the interconnected Marvel Universe and how stories and characters jump between titles. At other times I hate it. I think that mostly I hate it when I'm not familiar with what characters were doing in titles I haven't read, especially when I don't even know what titles those were. This was one of those times. I have a big feeling that once I go back and re-read Thunderbolts, in order, and make sure I fill in any missing volumes I'll enjoy this one quite a bit. I had mixed feelings At times I love the interconnected Marvel Universe and how stories and characters jump between titles. I had mixed feelings over how the comic was following three different stories, even if they were interconnected. It was nice though, that at the end, it felt like the three stories were for the most part wrapped up in a manner that the story could continue and start fresh. And lastly, I have to admit I tear up a little at the end during Songbird and Gunna's reunion. Seeing these two kick ass female characters who recently have been portrait as very emotionless during the recent history of the series open up and show emotion that leaves them open and exposed in some manners was very humanizing. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

MU-Map-0158-Booklet.Pdf (7.727Mb)

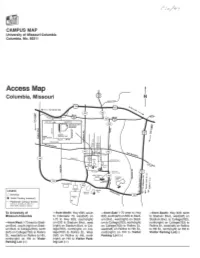

CAMPUS MAP -University of Missouri-Columbia Columbia, Mo. 65211 Access Map t Columbia, Missouri N I ~~/l~,M5auesr D ENTRANCE ~ "C I: cc VISI TOR dJ FROM PARKING ONLY PROVIDENCE AD ELM ST. ........ 740 63 s E 5 5 ! -~ ..o wrr :.:0 LEGEND D Buildings ~~~tt• Visitor Parking (metered) ····· Pedestrian Campus Streets 8:15 a.m. to 3:45 p.m. Mon.-Fri. when UMC classes in session To University of -from North: Hwy 63N, south -from East: I-70 west to Hwy -from South: Hwy 63S north Missouri-Columbia to Interstate 70, east(left) on 63S, south(left) on 63S to Stadi- to Stadium Blvd., west(left) on 1-70 to Hwy 63S, south(right) um Blvd., west(right) on Stadi- Stadium Blvd. to College(763), -from West: I-70 east to Stadi- on 63S to Stadium Blvd., west um to College(763), north(right) north(right) on College(763) to um Blvd., south (right) on Stadi- (right) on Stadium Blvd. to Col- on College(763) to Rollins St., Rollins St., west(left) on Rollins um Blvd. to College(763), north lege(763), north(right) on Col- west(left) on Rollins to Hitt St., to Hitt St., north(right) on Hitt to (left) on College(763) to Rollins lege(763) to Rollins St., West north(right) on Hitt to Visitor Visitor Parking Lot(*) St., west(left) on Rollins to Hitt, (left) on Rollins to Hitt, north Parking Lot (*) north(right) on Hitt to Vistor (right) on Hitt to Visitor Park- Parking Lot(*) ing Lot(*) 2 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 VGR-BFM-0086 toEltenslon DowntownColum~• A P11bticalions Dl1trlbutlonC1nter l0D11ryfum(32) (45) wtslonl-7010 Fayetteuil.2ml nwon40, enlrance onrlgh1 B El Pedestrian campus streets 8:15 am-3:45 pm Mon-Fri C during school term l§l Visitor parking -one way streets © Outdoor emergency phones to University Police D © Outdoor pay phones Access legend • accessible entrances curb cuts 1st first floor E G ground floor Parking for Visitors Central Campus Visitor Parking Lots - (1) Corner Hitt and Rollins streets (metered, four-hour time limit). -

{PDF EPUB} Thunderbolts Justice Like Lightning... by Kurt Busiek Thunderbolts #1 Was the Greatest Trick Marvel Comics Ever Pulled

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Thunderbolts Justice Like Lightning... by Kurt Busiek Thunderbolts #1 was the greatest trick Marvel Comics ever pulled. On March 10 Marvel launched a new mutant team in its long-awaited Children of the Atom #1 (which was delayed a year by COVID-19). But not all is as it seems (or was advertised) with the Children of the Atom, with the issue ending in a twist reveal about the heroes' identities. This isn't the first time Marvel has managed to hold on to a secret about a new 'superhero' team. Almost 25 years ago (in 1997 to be exact – mark your calendars to celebrate next year), Marvel capitalized on the absence of teams such as the Avengers and Fantastic Four who were then trapped in the Heroes Reborn dimension by building up a high-profile new team of superheroes called the Thunderbolts. (Incidentally, this year marks the 25th anniversary of Heroes Reborn, which Marvel is celebrating by reviving the title's branding for a new summer event). Created by writer Kurt Busiek and artist Mark Bagley, the Thunderbolts were led by Citizen V, an updated version of a Golden Age Marvel hero, and promised to deliver "Justice Like Lightning" (according to their tagline), to Avengers-level villains and threats. Marvel built the new team up as a group on par with Earth's Mightiest Heroes, ready to step up and save the world in the Avengers' absence. But Thunderbolts #1 ended with its own massive twist reveal about the true nature of the heroes of the Thunderbolts (spoiler alert: they were not new characters at all, but ones readers already knew – we'll get into it). -

MU-Map-0118-Booklet.Pdf (7.205Mb)

visitors guide 2016–17 EVEN WHEN THEY’RE AWAY, MAKE IT FEEL LIKE HOME WHEN YOU STAY! welcome Stoney Creek Hotel and Conference Center is the perfect place to stay when you come to visit the MU Campus. With lodge-like amenities and accommodations, you’ll experience a stay that will feel and look like home. Enjoy our beautifully designed guest rooms, complimentary to mizzou! wi-f and hot breakfast. We look forward to your stay at Stoney Creek Hotel & Conference Center! FOOD AND DRINK LOCAL STOPS table of contents 18 Touring campus works up 30 Just outside of campus, an appetite. there's still more to do and see in mid-Missouri. CAMPUS SIGHTS SHOPPING 2 Hit the highlights of Mizzou’s 24 Downtown CoMo is a great BUSINESS INDEX scenic campus. place to buy that perfect gift. 32 SPIRIT ENTERTAINMENT MIZZOU CONTACTS 12 Catch a game at Mizzou’s 27 Whether audio, visual or both, 33 Phone numbers and websites top-notch athletics facilities. Columbia’s venues are memorable. to answer all your Mizzou-related questions. CAMPUS MAP FESTIVALS Find your way around Come back and visit during 16 29 our main campus. one of Columbia’s signature festivals. The 2016–17 MU Visitors Guide is produced by Mizzou Creative for the Ofce of Visitor Relations, 104 Jesse Hall, 2601 S. Providence Rd. Columbia, MO | 573.442.6400 | StoneyCreekHotels.com Columbia, MO 65211, 800-856-2181. To view a digital version of this guide, visit missouri.edu/visitors. To advertise in next year’s edition, contact Scott Reeter, 573-882-7358, [email protected]. -

Sacks • Checchetto • Mossa 10

SACKS • CHECCHETTO • MOSSA 10 PARENTAL ADVISORY $3.99US 0 1 0 1 1 7 5 9 6 0 6 0 8 8 3 6 2 BONUS DIGITAL EDITION – DETAILS INSIDE! FORTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, THE WORLD’S SUPER VILLAINS ORGANIZED UNDER THE RED SKULL AND COLLECTIVELY WIPED OUT NEARLY ALL OF THE SUPER HEROES. FEW SURVIVED THE CARNAGE THAT FATEFUL DAY, AND NONE OF THEM UNSCATHED. THE UNITED STATES WAS DIVIDED UP INTO TERRITORIES CONTROLLED BY THE VILLAINS, AND THE GOOD PEOPLE SURVIVE IN THESE WASTELANDS AS BEST THEY CAN. AMONG THEM LIVES A FORMER HERO WHO’S GIVEN UP ON THAT WAY OF LIFE. HE IS CLINT BARTON, BUT SOME KNOW HIM AS… AN EYE FOR AN EYE PART 10 BLOOD FROM A STONE CLINT BARTON IS GOING BLIND. HE WANTS TO SEE THROUGH ONE FINAL MISSION — EXACTING REVENGE ON HIS FORMER THUNDERBOLTS COLLEAGUES THAT HELPED BRING ABOUT THE DEATHS OF THE AVENGERS— BEFORE HE LOSES HIS SIGHT FOR GOOD. HE’S TAKEN OUT ATLAS AND THE BEETLE, AND AFTER SUFFERING AN INJURY, TURNED TO FORMER CO-HAWKEYE KATE BISHOP TO HELP HIM COMPLETE HIS QUEST. IN HOPES OF REDEMPTION, BEFORE SHE DIED, EX-THUNDERBOLT SONGBIRD GAVE CLINT A MAP LEADING TO MOONSTONE, ANOTHER FORMER TEAMMATE. HOWEVER, THEY’LL HAVE TO MOVE QUICKER NOW THAT THE MARSHAL BULLSEYE SET HIS SIGHTS FIRMLY ON THE HAWKEYES… WRITER... ETHAN SACKS ARTIST... MARCO CHECCHETTO COLORIST... ANDRES MOSSA LETTERER... VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA COVER ARTIST... MARCO CHECCHETTO LOGO DESIGN... ADAM DEL RE GRAPHIC DESIGN... ANTHONY GAMBINO EDITOR... MARK BASSO EDITOR IN CHIEF... C.B. -

AKA Civil War Arc Mantles the Best Place in the Multiverse to Learn

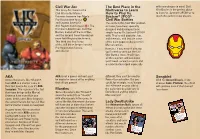

Civil War Arc The Best Place in the with new players in mind. Civil This Story Arc features the Multiverse to Learn War Battles is the perfect place Civil War in the Marvel How to Play Vs. to learn Vs. System® 2PCG® or to Universe between Iron Man’s System® 2PCG® – teach the game to new players. Pro-Registration forces ( ) Civil War Battles and Captain America’s The cards in this Civil War product, Anti-Registration forces ( ). The or Issue, have been specially ® first Giant-Sized Issue, Civil War designed and developed to be Battles, kicked off the Civil War, simple to play Vs. System® 2PCG® and the second Issue focused on with. They’re still powerful, fun, more Anti-Registration heroes. ® and thematic, and feature some This third and final Issue of the most popular characters in of Arc will delve deeper into the Marvel comics. Pro-Registration heroes, However, if you haven’t already, and villains! you’ll need to seek out the Civil War Battles Issue. It will have all the counters and Locations you’ll need, as well as cards and a rulebook developed especially AKA AKA is not a power and so it can’t different, they can’t be used to Songbird Some characters, like HVenomH, be copied or turned off by anything Power Up each other. But you With her Acoustikinesis, if she have AKA and another name in that affects powers. could, for example, have Venom chooses Sonic Platform, the effect their text box (in his case it’s AKA and HVenomH on your side at will continue even if she’s turned Scorpion). -

With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics Kylee Kilbourne

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 12-2017 With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics Kylee Kilbourne Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kilbourne, Kylee, "With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 433. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/433 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WITH GREAT POWER: EXAMINING THE REPRESENTATION AND EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN IN DC AND MARVEL COMICS by Kylee Kilbourne East Tennessee State University December 2017 An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment For the Midway Honors Scholars Program Department of Literature and Language College of Arts and Sciences ____________________________ Dr. Phyllis Thompson, Advisor ____________________________ Dr. Katherine Weiss, Reader ____________________________ Dr. Michael Cody, Reader 1 ABSTRACT Throughout history, comic books and the media they inspire have reflected modern society as it changes and grows. But women’s roles in comics have often been diminished as they become victims, damsels in distress, and sidekicks. This thesis explores the problems that female characters often face in comic books, but it also shows the positive representation that new creators have introduced over the years. -

Mizzou on Your Own

MIZZOU ON YOUR OWN FREE CELL PHONE AUDIO TOUR No cost except your minutes! • You set the pace. • Call as often as you like, and in any order. • Message length averages 2 minutes. • Uncover secrets, hear expert commentary and enjoy a more enriching campus visit! HERE’S HOW IT WORKS: 1. Visit any of the locations listed on the map (see reverse side) and look for a Mizzou Audio Tour sign next to the selected attraction. 2. Dial 573-629-1364 3. Enter the prompt number for the location you want followed by the # key. 4. Tell us what you think! Enter 0 followed by the # key to record a personal response to our audio tour (optional). For instructions, press the * key. Enter another location number anytime you want. The audio tour is free. You will use your cell phone minutes while you are connected. Technology provided by Guide by Cell. Sponsored by Elm St. 8 7 10 Sixth St. 9 6 5 11 University Ave. 3 12 13 14 Ninth St. 2 15 1 16 4 17 Conley Ave. FRANCIS ROUTE 1 Jesse Hall 2 Francis Quadrangle 3 The Columns 4 Hill and Townsend halls 5 Engineering shamrock 6 Switzler bell 7 Peace Park & bridge 8 Avenue of the Columns 9 School of Journalism 10 Journalism archway 11 Museum of Art & Archaeology 12 Residence on Francis Quadrangle 13 Thomas Jefferson statue & tombstone 14 Museum of Anthropology 15 David R. Francis bust 16 Barbara Uehling monument 17 Tate Hall Ninth St 43 41 42 Conley Ave 30 32 44 40 31 33 39 34 Hitt St 36 38 Rollins St 37 35 Tiger Ave CARNAHAN ROUTE 30 Conley House 31 Legacy Walk and Reynolds Alumni Center 32 Beetle Bailey 33 Carnahan Quadrangle 34 Tiger Plaza 35 Stankowski Field 36 Strickland Hall 37 Brewer Fieldhouse and Student Recreation Complex 38 MU Student Center 39 Kuhlman Court 40 Read and Gentry halls 41 Memorial Union 42 Ellis Library 43 Lowry Mall, Lowry Hall and the Student Success Center 44 Speakers Circle OTHER POINTS OF INTEREST BUCK’S ICE CREAM, located on the south side of Eckles Hall, is a great place to stop for a scoop of Tiger Stripe ice cream or other favorite flavors. -

A Songbird in Flames Taylor D

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works Spring 2019 A songbird in flames Taylor D. Waring Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.ewu.edu/theses Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Waring, Taylor D., "A songbird in flames" (2019). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 587. https://dc.ewu.edu/theses/587 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i A Songbird in Flames A Thesis Presented to Eastern Washington University Cheney, WA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing By Taylor D. Waring Spring 2019 ii Thesis of Taylor D. Waring approved by: Date: Name of Chair, Graduate Study Committee Date: Name of Member, Graduate Study Committee Date: Name of Member, Graduate Study Committee shades of blue sometimes your trés hombres cassette starts squealing over hot blue & righteous & you know billy is telling you something through the screeching erasure so you drive back home the long slow way through town down streets named after trees you’ve never seen in time for the sky’s pink organ to rupture into fleeing gold like the hopeful damned who conjured this burning land from bones & blood & sorrow & isn’t this your life this road that goes off far past that strange gold out into the helpless ocean? in this way the sound of water keeps you up at night in this way you’ll die praying for liquid light to reach your broken crown swearing you’ll kneel should the morning come & when it does don’t you wipe the dust from your eyes & look out the window at the crack in the concrete where you swore just yesterday a giant violet had burst through? 2 in this way i haze myself beyond infinite sorrow i.