A Story of Truth in Music Performance Christopher Mcrae University of South Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Popular Love Songs

Popular Love Songs: After All – Multiple artists Amazed - Lonestar All For Love – Stevie Brock Almost Paradise – Ann Wilson & Mike Reno All My Life - Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Always and Forever – Luther Vandross Babe - Styx Because Of You – 98 Degrees Because You Loved Me – Celine Dion Best of My Love – The Eagles Candle In The Wind – Elton John Can't Take My Eyes off of You – Lauryn Hill Can't We Try – Vonda Shepard & Dan Hill Don't Know Much – Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Dreaming of You - Selena Emotion – The Bee Gees Endless Love – Lionel Richie & Diana Ross Even Now – Barry Manilow Every Breath You Take – The Police Everything I Own – Aaron Tippin Friends And Lovers – Gloria Loring & Carl Anderson Glory of Love – Peter Cetera Greatest Love of All – Whitney Houston Heaven Knows – Donna Summer & Brooklyn Dreams Hello – Lionel Richie Here I Am – Bryan Adams Honesty – Billly Joel Hopelessly Devoted – Olivia Newton-John How Do I Live – Trisha Yearwood I Can't Tell You Why – The Eagles I'd Love You to Want Me - Lobo I Just Fall in Love Again – Anne Murray I'll Always Love You – Dean Martin I Need You – Tim McGraw & Faith Hill In Your Eyes - Peter Gabriel It Might Be You – Stephen Bishop I've Never Been To Me - Charlene I Write The Songs – Barry Manilow I Will Survive – Gloria Gaynor Just Once – James Ingram Just When I Needed You Most – Dolly Parton Looking Through The Eyes of Love – Gene Pitney Lost in Your Eyes – Debbie Gibson Lost Without Your Love - Bread Love Will Keep Us Alive – The Eagles Mandy – Barry Manilow Making Love -

Page 1 FLOATING STAGE CONCERTS THURSDAY 9TH

FLOATING STAGE CONCERTS WEDNESDAY 8TH JULY THURSDAY 9TH JULY FRIDAY 10TH JULY Sponsored by Westcoast 20.45 20.45 20.35 22.15 S O P H I E SARA COX MADNESS JAMES BLUNT PRESENTS ELLIS-BEXTOR JUST CAN’T GET ENOUGH 80s Sophie Ellis-Bextor shot to fame as a vocalist on If you’ve got fond memories of legwarmers and Spiller’s huge number one single Groovejet, followed spandex, ‘Just Can’t Get Enough 80s’ is a new show by Take Me Home and her worldwide smash hit, set to send you into a retro frenzy. Murder on the Dancefloor. Join Sara Cox for all the hits from the best decade, Her solo debut album, Read My Lips was released in delivered with a stunning stage set and amazing visuals. 2001 and reached number two in the UK Albums Chart Huge anthems for monumental crowd participation and was certified double platinum by the BPI. moments making epic memories to take home. Her subsequent album releases include Shoot from the Hip (2003), Trip the Light Fantastic (2007) and Make a Scene (2011). In 2014, in a departure from her previous dance pop Madness is a band that retains a strong sense of who and what it is. Ticket prices The five-time Grammy nominated and multiple BRIT award winning Ticket prices Ticket prices albums, Sophie embarked on her debut singer/songwriter Many of the same influences are still present in their sound – ska, Grandstand A £140 artist James Blunt is no stranger to festival spotlight and will the Grandstand A £140 Grandstand A £135 album Wanderlust with Ed Harcourt as co-writer and reggae, Motown, rock’n’roll, rockabilly, classic pop, and the pin-sharp Grandstand B £120 wow crowds at Henley Festival. -

Kathy Sledge Press

Web Sites Website: www.kathysledge.com Website: http: www.brightersideofday.com Social Media Outlets Facebook: www.facebook.com/pages/Kathy-Sledge/134363149719 Twitter: www.twitter.com/KathySledge Contact Info Theo London, Management Team Email: [email protected] Kathy Sledge is a Renaissance woman — a singer, songwriter, author, producer, manager, and Grammy-nominated music icon whose boundless creativity and passion has garnered praise from critics and a legion of fans from all over the world. Her artistic triumphs encompass chart-topping hits, platinum albums, and successful forays into several genres of popular music. Through her multi-faceted solo career and her legacy as an original vocalist in the group Sister Sledge, which included her lead vocals on worldwide anthems like "We Are Family" and "He's the Greatest Dancer," she's inspired millions of listeners across all generations. Kathy is currently traversing new terrain with her critically acclaimed show The Brighter Side of Day: A Tribute to Billie Holiday plus studio projects that span elements of R&B, rock, and EDM. Indeed, Kathy's reached a fascinating juncture in her journey. That journey began in Philadelphia. The youngest of five daughters born to Edwin and Florez Sledge, Kathy possessed a prodigious musical talent. Her grandmother was an opera singer who taught her harmonies while her father was one-half of Fred & Sledge, the tapping duo who broke racial barriers on Broadway. "I learned the art of music from my father and my grandmother. The business part of music was instilled through my mother," she says. Schooled on an eclectic array of artists like Nancy Wilson and Mongo Santamaría, Kathy and her sisters honed their act around Philadelphia and signed a recording contract with Atco Records. -

Current, January 24, 2011 University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2010s) Student Newspapers 1-24-2011 Current, January 24, 2011 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, January 24, 2011" (2011). Current (2010s). 68. http://irl.umsl.edu/current2010s/68 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2010s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAN. 24, 2011 VOL. 44; TheWWW.THECURRE CurrentN T-O N L I N E .COM ISSUE 1333 Sodexo is here, so what’s new? By Ryan Krull Page 2 PHOTO BY CHENHAO LI ALSO INSIDE Professor Mourned CAKE fans rejoice Nonverbal psychology 3 UMSL gives a memorial for Frank Moss 9 Cake’s latest album pleases fans old and new 10 Professor Miles L. Patterson’s new book 2 | The Current | JAN. 24, 2011 | WWW.THECURRENT-ONLINE.COM | | NEWS TheCurrent VOL. 44, ISSUE 1332 News WWW.THECURRENT-ONLINE.COM EDITORIAL Sodexo same as the old trough Editor-in-Chief...............................................................Sequita Bean News Editor.....................................................................Ryan Krull for professionalism and high course, would be good.” tional brands such as Einstein Features Editor.................................................................Jen O’Hara RYAN KRULL Sports Editor..............................................................Cedric Williams News Editor quality customer service.” Chartwells had been the Bros Bagels, Quiznos Subs A&E Editor.....................................................................William Kyle Diggs said that all Chart- food service provider for and Burger King. Although Assoc. A&E Editor........................................................Cate Marquis Although the semester wells employees were given UM-St. -

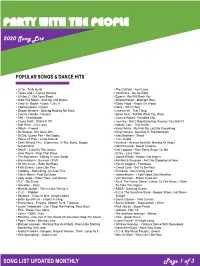

View the Full Song List

PARTY WITH THE PEOPLE 2020 Song List POPULAR SONGS & DANCE HITS ▪ Lizzo - Truth Hurts ▪ The Outfield - Your Love ▪ Tones And I - Dance Monkey ▪ Vanilla Ice - Ice Ice Baby ▪ Lil Nas X - Old Town Road ▪ Queen - We Will Rock You ▪ Walk The Moon - Shut Up And Dance ▪ Wilson Pickett - Midnight Hour ▪ Cardi B - Bodak Yellow, I Like It ▪ Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood ▪ Chainsmokers - Closer ▪ Nelly - Hot In Here ▪ Shawn Mendes - Nothing Holding Me Back ▪ Lauryn Hill - That Thing ▪ Camila Cabello - Havana ▪ Spice Girls - Tell Me What You Want ▪ OMI - Cheerleader ▪ Guns & Roses - Paradise City ▪ Taylor Swift - Shake It Off ▪ Journey - Don’t Stop Believing, Anyway You Want It ▪ Daft Punk - Get Lucky ▪ Natalie Cole - This Will Be ▪ Pitbull - Fireball ▪ Barry White - My First My Last My Everything ▪ DJ Khaled - All I Do Is Win ▪ King Harvest - Dancing In The Moonlight ▪ Dr Dre, Queen Pen - No Diggity ▪ Isley Brothers - Shout ▪ House Of Pain - Jump Around ▪ 112 - Cupid ▪ Earth Wind & Fire - September, In The Stone, Boogie ▪ Tavares - Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel Wonderland ▪ Neil Diamond - Sweet Caroline ▪ DNCE - Cake By The Ocean ▪ Def Leppard - Pour Some Sugar On Me ▪ Liam Payne - Strip That Down ▪ O’Jay - Love Train ▪ The Romantics -Talking In Your Sleep ▪ Jackie Wilson - Higher And Higher ▪ Bryan Adams - Summer Of 69 ▪ Ashford & Simpson - Ain’t No Stopping Us Now ▪ Sir Mix-A-Lot – Baby Got Back ▪ Kenny Loggins - Footloose ▪ Faith Evans - Love Like This ▪ Cheryl Lynn - Got To Be Real ▪ Coldplay - Something Just Like This ▪ Emotions - Best Of My Love ▪ Calvin Harris - Feel So Close ▪ James Brown - I Feel Good, Sex Machine ▪ Lady Gaga - Poker Face, Just Dance ▪ Van Morrison - Brown Eyed Girl ▪ TLC - No Scrub ▪ Sly & The Family Stone - Dance To The Music, I Want ▪ Ginuwine - Pony To Take You Higher ▪ Montell Jordan - This Is How We Do It ▪ ABBA - Dancing Queen ▪ V.I.C. -

Industry Newsletter

On The Radio December 2, 2011 December 23, 2011 Brett Dennen, The Kruger Brothers, (Rebroadcast from March 25, 2011) Red Clay Ramblers, Charlie Worsham, Nikki Lane Cake, The Old 97’s, Hayes Carll, Hot Club of Cowtown December 9, 2011 Dawes, James McMurtry, Blitzen Trapper, December 30, 2011 Jason Isbell & The 400 Unit, Matthew Sweet (Rebroadcast from April 1, 2011) Mavis Staples, Dougie MacLean, Joy Kills Sorrow, December 16, 2011 Mollie O’Brien & Rich Moore, Tim O’Brien The Nighthawks, Chanler Travis Three-O, Milk Carton Kids, Sarah Siskind, Lucy Wainwright Roche Hayes Carll James McMurtry Mountain Stage® from NPR is a production of West Virginia Public Broadcasting December 2011 On The Radio December 2, 2011 December 9, 2011 Nikki Lane Stage Notes Stage Notes Brett Dennen - In the early 2000s, Northern California native Brett Dennen Dawes – The California-based roots rocking Dawes consists of brothers Tay- was a camp counselor who played guitar, wrote songs and performed fireside. lor and Griffin Goldsmith, Wylie Weber and Tay Strathairn. Formed in the Los With a self-made album, he began playing coffee shops along the West Coast Angeles suburb of North Hills, this young group quickly became a favorite of and picked up a devoted following. Dennen has toured with John Mayer, the critics, fans and the veteran musicians who influenced its music. After connect- John Butler Trio, Rodrigo y Gabriela and Ben Folds. On 2007’s “Hope For the ing with producer Jonathan Wilson, the group began informal jam sessions Hopeless,” he was joined by Femi Kuti, Natalie Merchant, and Jason Mraz. -

MIZELL, Alfonce and Freddie Perren

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Manuscript Division Finding Aids Finding Aids 10-1-2015 MIZELL, Alfonce and Freddie Perren MSRC Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu Recommended Citation Staff, MSRC, "MIZELL, Alfonce and Freddie Perren" (2015). Manuscript Division Finding Aids. 136. https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/136 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Division Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALFONCE MIZELL AND FREDDIE PERREN COLLECTION Collection 72-1 Prepared & Revised by: Greta S. Wilson June 1980 ----------------------------------------------------------------- -------------- Scope Note The musical scores of Alfonce Mizell and Freddie Perren were presented to Moorland Spingarn Research Center on December 3, 1971. The seventeen scores, which were written and arranged primarily for the popular singing group, the "Jackson Five" are contained in one box measuring l/2 linear foot. Also contained in this box is a flyer and one photograph ----------------------------------------------------------------- MIZELL.Alfonce.FreddiePerren.TXT[11/13/2014 12:27:26 PM] -------------- - 2 - Series Description Series A Musical Scores Box 72-1 Popular music arranged and composed by Mizell and Perren for the singing group, "The Jackson Five"(* indicates material composed by them) Series B Broadside Box 72-1 One xerox copy of a flyer from the Howard University Jazz Institute announcing a class taught by Alfonce Mizell on the history of Jazz Series C Photograph Box 72-1 One photograph of members of "The Corporation", Deke Richards, Freddie Perren and Fonce Mizell, accepting awards at Broadcast Music Inc. -

Biography Armed with Some of the Greatest Songs Ever Written, The

Biography Armed with some of the greatest songs ever written, The Miracles are still after 40 years, attracting enthusiastic audiences around the world. Motown’s first of many famous groups such as The Temptations, The Four Tops, The Supremes, The Commodores, and The Jackson Five, and of course The Miracles the very first group to sign to Motown records, continue to keep the Motown sound alive by performing songs, such as: “Shop Around”, “I Second That Emotion”, “Tears Of A Clown”, “Love Machine”, “You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me”, “The Tracks Of My Tears”, “Ooh Baby Baby” and many more. Their performances at the Nassau Coliseum, the Inaugural Gala in Washington, D.C. and the 4th of July celebration at Duke University with over 60,000 fans in attendance, was simply unbelievable. In 1956, Bobby Rogers, Smokey Robinson, Claudette Robinson, Ronnie White and Pete Moore, childhood friends became The Miracles, and embarked on a career that would surpass their wildest dreams. Berry Gordy Motown’s founder recorded and released “Shop Around” a number one smash on all the charts, establishing The Miracles and giving Motown their first gold seller, this was the beginning of the record company and the group success for many years to come. The Miracles and Motown Records became known throughout the entire world. Over the course of the years, The Miracles continued to record chart-topping hits, including “Ooo Baby Baby”, “Going To A Go-Go”, “More Love”, “Mickey’s Monkey” and “Tears Of A Clown”. The Miracles established themselves as one of the best groups of all times. -

International Journal of Education & the Arts

International Journal of Education & the Arts Editors Eeva Anttila Terry Barrett University of the Arts Helsinki University of North Texas William J. Doan S. Alex Ruthmann Pennsylvania State University New York University http://www.ijea.org/ ISSN: 1529-8094 Volume 15 Number 19 November 1, 2014 Deepening Inquiry: What Processes of Making Music Can Teach Us about Creativity and Ontology for Inquiry Based Science Education Walter S. Gershon Kent State University, U. S. Oded Ben-Horin Stord/Haugesund University College, Norway Citation: Gershon, W. S., & Ben-Horin, O. (2014). Deepening inquiry: What processes of making music can teach us about creativity and ontology for inquiry based science education. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 15(19). Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v15n19/. Abstract Drawing from their respective work at the intersection of music and science, the co- authors argue that engaging in processes of making music can help students more deeply engage in the kinds of creativity associated with inquiry based science education (IBSE) and scientists better convey their ideas to others. Of equal importance, the processes of music making can provide students a means to experience another central aspect of IBSE, the liminal ontological experience of being utterly lost in the inquiry process. This piece is also part of burgeoning studies documenting the use of the arts in STEM education (STEAM). IJEA Vol. 15 No. 19 - http://www.ijea.org/v15n19/ 2 Principles for the Development of a Complete Mind: Study the science of art. Study the art of science. Develop your senses – especially learn how to see. -

GLORIA GAYNOR Is All About Adapting, Evolving and Celebrating Life’S Triumphs, Big and Gloria Gaynor Small

INTERVIEW 39 EDGE er first Top 10 hit examined how hard it is to leave the man you love. Her signature Hsong a few years later celebrated the act of booting him to interview the curb. GLORIA GAYNOR is all about adapting, evolving and celebrating life’s triumphs, big and Gloria Gaynor small. From her teen years in Newark as an aspiring entertainer to her ascent to Disco Diva, she has not only survived, she has thrived. As EDGE Assignments Editor ZACK BURGESS discovered, Gaynor has learned a thing or two about herself and others along the way. Still going strong more than four decades after first taking the stage, she is not an easy woman to slow down—even when examining her remarkable achievements and indelible music legacy. EDGE: You have quite a résumé in Soul, Gospel and R&B. Yet most people associate you with Disco. Is that a good thing or a bad thing? GG: It’s kind of a double-edged sword. People who like disco music and associate me with it, I think that’s great. But when people who like other genres don’t associate me with those genres, well that’s not a good thing. EDGE: As disco faded in the 1980s, did that affect your career? GG: Yes, it did. I received fewer calls from the United States to perform. EDGE: During this time did you find Photo courtesy of Troy Word yourself drawing strength from the VISIT US ONTHE WEB www.edgemagonline.com 40 INTERVIEW EDGE: Does your fan base differ overseas compared to the U.S.? GG: Not a lot. -

Soul: a Historical Reconstruction of Continuity and Change in Black Popular Music Author(S): Robert W

Professor J. Southern (Managing Editor-Publisher) Soul: A Historical Reconstruction of Continuity and Change in Black Popular Music Author(s): Robert W. Stephens Source: The Black Perspective in Music, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Spring, 1984), pp. 21-43 Published by: Professor J. Southern (Managing Editor-Publisher) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1214967 Accessed: 02-01-2018 00:35 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Professor J. Southern (Managing Editor-Publisher) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Black Perspective in Music This content downloaded from 199.79.168.81 on Tue, 02 Jan 2018 00:35:51 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Soul: A Historical Reconstruction of Continuity and Change in Black Popular Music BY ROBERT W. STEPHENS rT r aHE SOUL TRADITION is a prime cultural force in American popular music; of that, there can be little doubt, although this musical phenomenon is sometimes vaguely defined. Born of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements of the 1960s, soul has provided a musical and cultural foundation for virtually every facet of contemporary popular music. More important than its commercial successes, however, are the messages and philosophies it has communicated and the musical influences which underlie its development. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 1-27-2011 The aC rroll News- Vol. 87, No. 12 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 87, No. 12" (2011). The Carroll News. 832. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/832 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comedy with benefits: Staying fit: Ashton Kutcher and Corbo weight room Natalie Portman gets new layout, star in “No Strings equipment, p. 3 Attached,” p. 7 THE Thursday, JanuaryARROLL 27, 2011 EWSVol. 87, No. 12 C The Student Voice of John Carroll University N Since 1925 Track and field scheduled for updates Dan Cooney the project as a re- of disappointment,” she said. Campus Editor placement for the Dietz said the University turf and track. is working with a track con- Preliminary plans are in place “The track coach- sultant to help them specify for upcoming improvements to es, quite frankly, different products for the track. the playing field and track at Don have been wined and The consultant was a former Shula Stadium at Wasmer Field. dined by a lot of Olympian. The project will include laying the manufacturers’ “He would never recom- down new turf and rebuilding reps for some really mend to us a product that was and resurfacing the entire track high-end products, subpar,” Dietz said.