Exploring Global Identities at the Central Idaho School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NILES HERALD -SPECTATOR M HOME, Mlocinews SINCE 1951

NILES HERALD -SPECTATOR M HOME, MLociNEWS SINCE 1951. 1btì 'i iiii ti i INSIDE THE 2015 CAMP GUIDI Stemming the tide Nues Stormwater Commission looks at flood projects I PAH Nues Herald-SpectatorI ©2015 Chicago Tribune Media Group All rights reserved Balance Transfer 1ates For One Full Year As LOW As 1O SOC-.TOg11 S311N .LS NOj>0j DOOOO 0959 2 u75°' isla L0J.NW : N..Lt' 5T0.LOlOOOOOO5TO 3*ui*95896O I1WCCLICOIB.......«'. 847.647.1030 THURSDAY JANUARY 29 2015 A PIONEER PRESS PUBLICATION NIL MARINO REALTORS 5800 Dempster-Morton Grove (847) 967 5500 (OUTSIDE ILLINOIS CALL i - 800 253 - 0021) MLS The Gold Standard a www.century2l marino.com THE CROSSINGS OF MORTON GROVE! THE VALUE IS HERE! STEPS TO FOREST PRESERVE TRAILS! .. Morton Grove. Luxurious & Contemporary RowMorton Grove... Charming 1400 sq It, 3 bedroom - 1.5 bathMorton Grove.. Meticulous 9 room brick Bi-level located Home buitt by Toll Brothers! Convenient location nearhome with huge 2.5 car insulated garage. Garage measuresconvenient to forest preserve bike/bridle trails,school & Metra Station, Forest Preserves, Bike/Bridle/Running27 feet deep & 23 ft wide plus an 8 foot high garage door parK/pool! Hardwood floors in living room/dining room & trails, Park, Pool, Library & Park View School. Stunningincluding loft space above parking area. Large Kitchen, freshly 2nd level. 3 bedrooms & 2 full baths. Kitchen with newer Granite kitchen with 42" cabinets, island + separatepainted inside home & garage, Hardwood flooring throughout countertop, sink & appliances. Lower level with rec room, eating area leads to balcony. i st floor family rm withincluding under the carpet. -

Colorado Kayak Supply Blog 1/20/10 11:33 AM

Wilderness Systems Commander 120 Recreational Kayak Review | Colorado Kayak Supply Blog 1/20/10 11:33 AM Colorado Kayak Supply Blog The Colorado Kayak Product Review Website Home Information About us Colorado Kayak Supply CKS Squad Gear Pics Recreational Boating and Touring Blog « It’s Cold Outside, Good Thing I’m Wearing Plaid. Wilderness Systems Commander 120 Share This Post! Recent Posts Share This blog! Wilderness Systems Commander Recreational Kayak Review | More 120 Recreational Kayak Review It’s Cold Outside, Good Thing I’m January 18th, 2010 by CKS | Posted in Boats, Dagger, Wilderness Systems Commander 120 Product Reviews Wearing Plaid. The Dagger Axis 10.5 and 12 All 350.org Water Adventure Kayak CKS FaceBook Photo Contest Rollin’ On Gravy Wheels Results Liquid Logic Coupe Sit On Top CKS Summer Sale 09! Whitewater Kayak Review CKS Summer Sale and Gear Swap 2009 Product Reviews Accessories 661 Race Elbow Pads Stay Up To Date On New Grand Trunk Hammock 2009 Gear Reviews- Boats BOAT REPAIR Subscribe Here! Dagger Your email: Agent Enter email address... Atom Crawford Reviews The Nomad 8.5 Subscribe Unsubscribe Axis 10.5 and 12 Green Boat Kingpin Series Visit us on Facebook Mamba Series Colorado Kayak Supply - CKS Nomad 8.1 and 8.5 Wilderness Systems Commander 120 Jackson 2010 JAckson Fun Series All Star 2010 All Star Review with Eric Jackson Jackson All Star Photos From Summer 2008 Leif Embertson Reviews the 2010 All Star Wilderness Systems Commander 120 Review Paddler Reviews Earl Richmond The Commander, is Wilderness Systems answer to the Native Watercraft Ultimate Series. -

Canoe Accidents Rived, and Juliano Was Taken on Board and Rushed to a Waiting Ambulance at the Poplar a Woman Drowned After a Canoe She and Video Put-In

BANKSIDE IN A TENT, STAKING YOUR TURF IN A CROWDED RV THE BACK BED OF A LUXURIOUSLY DECKED-0UT.PICK-UP NO MATTER WHAT THE ACCOMMODATIONS (OR LACK THEREOF), YOU KNOW THAT YOUR SOUL SLEEPS MORE PEACEFULLY ALONGSIDE THE RIVER THAN ANYWHERE ELSE IN THE UNIVERSE. WE KNOW THE FEELING. IN FACT, WEW DEO~CAKD OURSELM&O IT. AND YOU CAN SEE IT IN OUR WHITEWATER BOAT DESIGNS. BOATS LIKE THE NEW AMP- A REVOLUTIONARY NEW DESIGN THAT ALLOWS YOU TO PLUG DIRECTLY INTO THE CURFENT OF THE RIVER. THIS SERIOUSLY ADVANCED WHllEWATER SCENARIO WILL PUSH.KAYAKING TO A NEW EXTREME. SO WHEREVER YOUR SOUL SLEEPS, MA& SO% IT GETS -A GOOD NIGHT'S REST. BECAUSE, THANKS TO NEW BOATS LIKE THE AMP, ITS GOMNA-NEED IT FOR'A FREE CATAL~1-wss-KAYAK O R W.WYAKER.COIU ! forum ...................................... 4 r Whitewater Love Touble by Bob Gedekoh Director's Cut .................................. 16 by Rich Bowers , Conservation .................................. 22 .I American Whitewater Has Come a Long Way r Members Tell off Congress on Fee Demo r Flow Studies on Chelan and Cheoah r Top 40 Riwr Issues Access .......................... ...... 42 r Why American Whitewater Sued the Grand Canyon IDon't Park on My Frouerty Events ..................................48 INOWR Events News and Results r Schedule of River Events 2000 Safety .........I..................I.....** 92 % r Whitewater Fatalities Drop Slightty r Kayaking is Safer Than You Think River Voices ....................... .. ......... 102 r Losing Your Fear of Holes E The Biflh of Tude / r The Rayaking Image .I Whitewater Injury SuMeY Briefs .................................106 r Announcing WWW.Amertcan Whitewater.org F r Emergency Rebreather SUN~Y Cover Photos : Back: Tom Vickery freewheels fourth drop of Eagfe Falls on the Beaver, NY. -

Kayaking Event Hosted by Your Commu- Immediately

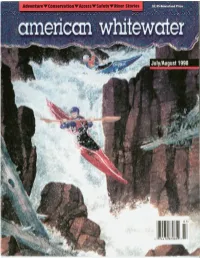

Letters ......................................7 Forum ...................................... 4 r Blame by Bob Gedekoh Briefs .....................................76 r Membership Maniacs Wanted Portrait of a Whitewater r A Beginner Dream Come True r North American Water Trails COnferenCt! Artist... Meet Movt Reel r Watauga Gorge Race by Bob Gedekoh 38 r Ocoee Double Header River Voices ................................... 64 New River DrysY by Tim Daly 46 r A Letter from Rosl r First Swim r ~i~~ingHer softly ... r The Wet Ones CotingI u with Cabin Fever r The Lek Hole by Rick Danis 49 r Waller's Rules of the River r Whitewater in Belgium? A Rite of Friendship... Conservation .................................. 16 r Director's Cut Paddling the Rocky Broad r Profile: Kevin Lewis r Smell the Flowers Remembering Pablo Perez V r Rivers: The Future Frontier by Leland Davis 52 Safety .................................... 62 Cover: Painting donated to American Whitewater by Hoyt r Who We Are, and What We Do Reel ... to be sold at Gauley Fest 1998. See story inside. by Rich Bowers Publication Title: American Whitewater Access .................................. 25 Issue Date: July/ August 1998 Statement of Frequency: Published bimonthly r Girl Scouts Towed While Rafting Authorized Organization's Name and Address: r Oregon Rules American Whitewater Nature Lovers vs. Developers P.O. Box 636 r Margretville, NY 12455 r Help the Grand Canyon Events .................................. 32 r AWA Events Central r 1998 Schedule of River Events r 1998 NOWR Events Results Printed on Recycled Paper American Whitewater July/ August 1998 cheap, sarcastic, and lazy): my tendency to blame other people for my misfortunes. This is a failing that my mother decried when I was still a child. -

Watauga Perception" ONE Wlth WATER

7 'Carts $4.95 Newsstand Dvi~e First he... Nantahala, Upper YougP - -- -'Watauga perception" ONE WlTH WATER [ we started ~erception"back in the '70s. ] SO 'IOU'LL UlvOEHSTANO IF THE EXACT OATE IS A LITTLE FUZZ'J. WE WERE'DOING A LOT OF THINGS BACK IN THE '70s, BUT WHAT WE WERE DOING MOST WAS PADDLING. WHICH IS HOW PERCEPTION GOT STARTED. WlTH A BUNCH OF PADDLERS WHO WERE WAY INTO KAYAKING AND WANTED TO PADDLE THE BEST BOATS IMAGINABLE. 23 YEARS LATER, WE'VE GROWN INTO THE WORLD'S LEADING MANUFACTURER OF MODERN KAYAKS. WE'VE PADDLED MORE WATER, CREATED MORE INNOVATIONS AND INTRODUCED MORE PEOPLE TO THE SPORT OF KAYAKING THAN ANY OTHER BOAT MAKER. YOU MIGHT SAY WE'VE COME A LONG WAY SINCE THE '70s. MAYBE. BUT THEN AGAIN, MAYBE NOT. FOR A COPY OF OUR NEW 1999 CATALOG, GIVE US A CALL AT 1-800-59-KAYAK. 01999 Perception, Inc. www.kayaker.com Departments Forum ......................................4 Features r Before You Leap by Bob Gedekoh Thirty years of the Tuolumne Director's Cut ....................................7 1 by Jerry Meral by Rich Bowers Letters ..................................... .8 Conservation .................................. 19 r All Dams Fail r Remove Dams, Restore Salmon r Power Supports American Whitewater Restoration "The Palguine" I 1 by John Moran 43 Access .................................. 26 r Chatooga Section 0,00, and 1 A Near Disaster in E uador r Legislative Update on NC Boater Tax by Poll~Green r California Senate Approve Yuba Wild and I ----id Scenic Bill r Fees on Upper Yough First Time r AW intern researching Grand Canyon Wilderness Management Plan When you are a beginner. -

Chile's Volcanic Whitewater Page 38

Chile's Volcanic Whitewater page 38 Gore Race page 61 t the wed. the pion. o ahead, get creative. Now you've got the Whiplasw and Whip-It": two new playboats with planing hulls and performance rails, to fit any body. Ingenious? Undoubtedly. Artistic? That's up II to you. Team member, Shane Benedict Photo by: 1 Christopher Smith 1 11 kayaker way easley, s.c 29642 1 -800-262-0268 httpd/www. I kayaker.com Journal of the American Whitewater Volume XXXVII, No.6 Letters ......................................6 Forum ......................................4 Rio Truful-Truful- r Perspectives on the Edge bv Scott Hardina 38 by Bob Gedekoh Briefs .................................... 88 The Clarks Fork of r Upper Yough Race r Canoeing for Kids r KidsKorner the Wowstone by Earl Alderson 42 River Voices ................................... 75 r Hole ousting A Circus r Makin' the Move r Stuck in a Hole on the Selwav- r Canoeing the River by Train by Gary Baker 48 Conservation .................................. 13 r Director's Cut Where Credit is Due! r AW's Distinguished Friends of Whitewater Safety .................................... 66 America's Best... r Benchmark RapidsNS Standard Rated Rapids by Lee Belknap Dana Chladek! r Incident Management by John Weld 51 by Robert Molyneaux Access .................................. 19 r Whitewater Boating is a Crime in Yellowstone Sherlock! r Access Updates What's that duck? Humor .................................. 95 by April Holladay 57 r ~cid~ock Cover: Photo by Todd Patrick Charlie Macarthur, having a great run before performing a by Dr. Surf Wavehopper splat in the middle of Kirshbaums's Rapid r Deep Trouble by Jonathan Katz Events .................................. 22 r AWA Events CentralIGauley Fest Report r Membership Mania Printed on Recycled Paper r Report from the Ottawa Worlds Publication Title: American Whitewater Issue Date: November / December 1997 Statement of Frequency: Published bi-monthly Authorized Organization's Name and Address: American Whitewater P.O. -

Pocket-Sized Rafts Father, Son Canoe Trip

BY BOATERS FOR BOATERS March/April 2006 Inf latables Canoes Pocket-Sized Rafts Make Wilderness Adventure a Breeze Father, Son Canoe Trip Turns Wet and Cold Call Clay Wright a . Rafter! Paddling as Therapy: Kayaking Instruction Helps Injured Vets’ Rehab page 18 Kayak Camp for Kids with Cancer page 30 A VOLUNTEER PUBLICATION PROMOTING RIVER CONSERVATION, ACCESS AND SAFETY American Whitewater Journal March/April 2006 DEPARTMENTS 3 The Journey Ahead by Mark Singleton 4 Book Review: Northwood Whitewater by Steve Corsi 5 AW News & Notes 7 History: Whitewater Canoes: Twists and Turns by Sue Taft 8 Field Notes: Call Me a Rafter by Clay Wright 60 Corporate Sponsors 62 Locals Favorite: Spencer’s by Dan Rubado 64 Accident Report by Charlie Walbridge 66 The Last Word by Ambrose Tuscano 68 Donor Profi le by Nancy Gilbert RIVER STORIES 12 Rio Sirupa by James “Rocky” Contos FEATURE - Infl atables & Canoes - Paddling as Therapy Infl atables & Canoes 10 My Cat’s Meow by George Brown 26 Packrafts: Simple Adventure by Jim Jager 52 My Lapland Adventure by Michael Moran 66 The Last Word by Ambrose Tuscano Paddling as Therapy 18 Yellow Ribbons and White Water byby PhilPhil SayreSayre and AdamAdam CampbellCampbell 30 First Descents: Kayaking Camp for Cancer Survivors 56 Kayaking: My Cure for Kayaking by Brock Royer EVENTS 40 Cheoah River Celebration by Kevin Colburn STEWARDSHIP 42 Cheoah River Revival Party 43 Dam Owner Goes After the Clean Water Act by Thomas O’Keefe 46 Sultan River Releases for Three Days in December by Thomas O’Keefe 48 Colorado Water Rights Battle by Kevin Natapow CFC UnitedWay #2302 Support American Whitewater through CFC or United Way All the federal campaigns, and a few of the local United Way campaigns will allow you to donate through them to AW. -

Adventure Rec

ADVENTURE REC The Kaos is half sit-on-top kayak, half longboard surfboard, all parts fun! The Zydeco is performance-engineered for flat and slowly moving water with enough The Kaos accelerates quickly, carves, and rushes big coastal breakers with confidence. maneuverability for lazy rivers and enough speedy acceleration for the lake. 10.2 9.0 11.0 Length: 10' 2" / 314 cm Length: 9' 1" / 276 cm Length: 11' 2" / 340 cm Width: 26.5" / 67 cm Width: 28.5" / 72 cm Width: 27.75" / 70 cm Boat Weight: 43 lbs / 20 kg Boat Weight: 36.5 lbs / 17 kg Boat Weight: 48 lbs / 22 kg WHITEWATER Boat Specs. BOAT LENGTH WIDTH DECK HEIGHT COCKPIT VOLUME WEIGHT RANGE BOAT WEIGHT Seat Backrest/ Back Band Pad Seat Thigh Braces Brace Foor Bar Security Beginner Intermediate Advanced Stability Maneuverability Hull Speed How We Get Them. What They Mean. You The Boat Axiom 6.9 6' 9"/206 cm 22.5"/57 cm 10.5"/27 cm 27.75"x17"/71 x 43 cm 39 gal/148 L 65-120 lbs/29-54 kg 24 lbs/11 kg T PA TV AP AK H 4 5 4 4 4 5 WEIGHT Axiom 8.0 8'/244 cm 24.5"/62 cm 12"/30 cm 34" x 19"/86 x 48 cm 51 gal/193 L 90-150 lbs/41-68 kg 36 lbs/18 kg R RA CE PA B H 4 5 5 4 4 5 Based on a fully assembled boat including all outfitting. Axiom 8.5 8' 6"/259 cm 25.5"/65 cm 13.5"/34 cm 34" x 19"/86 x 48 cm 63 gal/238 L 130-210 lbs/59-95 kg 40.5 lbs/19 kg R RA CE PA B H 4 5 5 4 4 5 (NOTE: When comparing, other companies may not include outfitting in their weight specifications.) Axiom 9.0 9'/274 cm 27.75"/69 cm 14"/36 cm 34" x 19"/86 x 48 cm 78 gal/295 L 180-265 lbs/82-120 kg 45 lbs/20 kg R RA CE PA B -

International Paddling Domestic Travel

BY BOATERS FOR BOATERS January/February 2006 International Paddling Saving Ecuador’s Pristine Whitewater A 330-mile Solo Descent in Mexico Great Places to Paddle (Besides the U.S.) Domestic Travel Nothing But Paddling for a Month? Gettin’ Busy: 3 Rivers in 1 Day A VOLUNTEER PUBLICATION PROMOTING RIVER CONSERVATION, ACCESS AND SAFETY American Whitewater Journal January / February 2006 DEPARTMENTS 3 The Journey Ahead by Mark Singleton �������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Letters to the Editor ��������������������������� ����������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������� 5 AW News & Notes ������������������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������� 9 History: Bob McNair: Whitewater Pioneer by Sue Taft ������������� ����������������������������� ��������������������������������������� by Clay Wright ������������������ 10 Field Notes: Boating Beyond the Border �� 14 Locals’ Favorite: Snake River Canyon WY by Christie Glissmeyer 46 Events: Green Race, Russell Fork Race, Heff Festival 64 Humor: The Seven-Year Itch by Julia Franks �� ������������������� -

Otter Bar 2009

CZlhaZiiZg '%%-HZVhdcl^i]'%%.=^\]a^\]ih %.The winter of 2007 – 2008 produced above average precipitation with a normal snow pack and an unusual amount of low snow that stuck around for months. This increased the ground water dramatically as slow melting snow seems the best contributor to the aquifer. Our early season was very slow which has prompted us to make some changes in 09 (see dates). Late May June and July were booking well when all of California experienced a fierce lightening storm on June 21. This started numerous fires all over the state including several in our area. We began to be intermittently effected by smoke and after several weeks it was apparent that one of the fires was going to reach our property. We closed in mid July due to smoke, road closures, and the chaos of a dramatic increase in fire fighting crews and overhead. We remained closed for a month as the fire made it’s way to us and burned the length of our property above the road It was largely a “good” fire and was of low intensity. We were hugely relieved to have it go by us without the devastation of a hot “crowning” fire. We were very fortunate to have a great deal of help from the Federal government. At one point we had three engine crews on AD9<: the property, three pumps and five thousand feet of hose lay. This was an extremely stressful time as we never knew what changes to fire behavior could occur based on the weather. We survived with the forest still in great shape and reopened in mid August. -

2016 Dagger Is a Registered Trademark of Confluence Outdoor

There was a time when surfing and throwing tricks was for the experts. But today, innovative freestyle designs have opened the thrilling experience that is park, play, and FREESTYLE owning the wave to anyone. Whether you’re into surfing and spinning on your way down river or defying gravity with massive air moves in competitions, Dagger invites all those who come to play. JITSU 5.5 JITSU 5.9 JITSU 6.0 While arguably the loosest freestyle hull on the market The Jitsu 5.9 excels at performing three dimensional Out-performing competitor freestyle kayaks downriver, today, the Jitsu 5.5 maintains snappy edge-to-edge combination moves in advancing hole play while creating a the Jitsu 6.0 is for larger paddlers who want to enjoy transition for smaller framed paddlers. seamless blend of speed, looseness and release on waves. big waves, holes on river and freestyle competition too. Length: 5' 6" / 168 cm Length: 5' 9.5" / 178 cm Length: 6' 0" / 183 cm Paddler Weight Range: 90-155 lbs / 41-70 kg Paddler Weight Range: 140-200 lbs / 64-91 kg Paddler Weight Range: 165-245 lbs / 75-111 kg Boat Weight: 29 lbs / 13 kg Boat Weight: 31 lbs / 14 kg Boat Weight: 32 lbs / 15 kg Outfitting: ConTour Ergo System Outfitting: ConTour Ergo System Outfitting: ConTour Ergo System Seating: Roto Molded Seating with Leg Lifter Seating: Roto Molded Seating with Leg Lifter Seating: Roto Molded Seating with Leg Lifter Back Band: Ratchet Adjustable Back Band Back Band: Ratchet Adjustable Back Band Back Band: Ratchet Adjustable Back Band Structure: Welded-In Seat Track Structure: