Almatourism Special Issue N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Mission Handbook, 14th edition, Canada/USA Protestant Ministries Overseas. Edited by W. Dayton Roberts and John A. Siewert. Monrovia, Calif.: MARC (Mis sions Advanced Research and Communi cation Center), 1989. Pp. 550. Paperback $23.95. This comprehensive reference work, Ministries Overseas to Canada/USA Protcussing the relationship between church published approximately every four estantMinistries Overseas. The 14th edi and parachurch missionary efforts. years, is an indispensable tool for those tion carries statistical data for Canada Christy Wilson gives a brief state who are leaders, participants, and sup and the United States separately, with ment on Tentmakers, alluding to an porters of the missionary endeavor of out offering combined totals for North unsubstantiated statistic that 80 per the church. It is essential to the work America, making comparisons with cent of the unreached people groups of a broad range of people, including: previous editions a bit cumbersome. are in restricted areas. scholars and leaders of missionary While statistics and directory in In a rather strange treatise, Arthur agencies, training institutions, and formation constitute most of the book, Glasser uses the title "That the World churches. the introductory chapters provide a May Believe" to paint a negative pic Readers of the new Mission Handhelpful context. In an article entitled ture of associations of missions that seek book should note a change in the sub "A Unique Opportunity," William to serve missions and increase their title: from North American Protestant Dyrness provides descriptive glimpses networking and cooperation. This of churches around the world. chapter would have been more 'appro In "The Sending Body," Sam priate as an editorial in a periodical than Wade Coggins, retiring Executive Director of uel Moffett reviews and evaluates the as a chapter in an important reference EFMA (Evangelical Foreign Missions Associasending base of North America, mak work. -

History and Ecumenics Courses, 2014-2016

June 11, 2014 History and Ecumenics Church History Early/Medieval CH1100 Survey of Early and Medieval Church History The life and thought of the Christian church from the apostolic period to the eve of the Reformation. Lectures and group discussions of brief writings representative of major movements and doctrinal developments. Designed as an orientation to the shape of the whole tradition in its social setting. • This course fulfills the early/medieval church history requirement. • 3 credits. Fall Semester, 2014–2015; Ms. McVey Fall Semester, 2015–2016; Mr. Rorem CH3212 Introduction to the Christian Mystical Tradition An investigation of the theological and philosophical roots, the motifs, practices, and literary expressions of Christian mystical piety with special attention given to selected medieval mystics. Discussions, lectures, interpretations of primary sources. • This course fulfills the early/medieval church history requirement. • 3 credits. (Capstone course) Fall Semester, 2014–2015; Mr. Rorem CH3215 Syriac Christianity and the Rise of Islam The history of Christianity in the Syriac-speaking world from the Apostle Thomas through the early Islamic period. Living at the eastern boundaries of the Roman Empire, at the edge of Arabia, and in the Persian Empire, Syriac Christians lived in a multicultural and multi-religious context. Course themes include early Jewish Christianity, theology through poetry and hymns, female theological language, Christology and biblical interpretation, early missions to India and China, the possibility of Christian influence on the Qur’an and nascent Islam, and life under early Muslim rule. This course fulfills the early/medieval church history requirement. Pass/D/Fail. 3 credits. (Capstone course) Fall Semester, 2014–2015; Ms. -

What Can Adventists Learn from Jews About the Sabbath the Holistic Spirituality of Ellen White Congratulations! Now What? Q&A with Mt

We Dig Dirt: Archeology at Tell ‘al Umayri What Can Adventists Learn from Jews About the Sabbath The Holistic Spirituality of Ellen White Congratulations! Now What? Q&A with Mt. Ellis Academy’s Principal Through the Lens of Faith VOLUME 39 ISSUE 1 I winter 2011 winter 2011 I VOLUME 39 ISSUE 1 SPECTRUM contents 11 Editorials 2 A Time to Mourn | BY BONNIE DWYER 3 Memo to Elder Wilson | BY CHARLES SCRIVEN Feedback 15 5 Letters | BAKER, OSBORN, WILLEY, EUN, CARR, ROTH, WILL, BULL, GUY Biblical Studies: Sabbath 11 The Sabbath and God’s People | BY GERALD WHEELER 15 What Can Adventists Learn from the Jews about the Sabbath? | BY JACQUES B. DOUKHAN 21 21 My Celtic Sabbath Journey with Esther, Lady MacBeth, and St. Brigid | BY BONNIE DWYER 31 Negotiating Sabbath Observance in the Local Church | BY JOHN BRUNT Archeology 37 We Dig Dirt: Archeology at Tell ‘al Umayri | BY JOHN MCDOWELL 31 Spiritual Journeys 43 The Holistic Spirituality of Ellen White | BY HARRI KUHALAMPI 52 The Art of Intervention: Finding Health in Faith | BY HEATHER LANGLEY 56 Through the Lens of Faith | BY MARTIN DOBLMEIER 62 Capturing Spiritual Moments—Digitally | BY RAJMUND DABROWSKI 36 Adventist Education 66 Time to Act: Strong Convictions Expressed at a National Summit on Adventist Education | BY GILBERT M. VALENTINE 77 Congratulations! Now What? Q & A with Mt. Ellis Academy’s Principal Darren Wilkins | BY JARED WRIGHT 43 Poetry cover She Presents a Paper on the Theory of Everything | BY MIKE MENNARD 77 66 62 56 52 WWW.SPECTRUMMAGAZINE.ORG I CONTENTS EDITORIAL I from the editor A Time to Mourn | BY BONNIE DWYER esus Wept. -

A Case Study of the Eastern Cuba Baptist Theological Seminary

THEOLOGICAL HIGHER EDUCATION IN CUBA: A CASE STUDY OF THE EASTERN CUBA BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY Octavio J. Esqueda, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2003 APPROVED: D. Barry Lumsden, Major Professor Michael S. Lawson, Minor Professor John G. Plotts, Committee Member Ronald W. Newsom, Program Coordinator for Higher Education Michael Altekruse, Chair of the Department of Counseling Development and Higher Education M. Jean Keller, Dean of the College of Education C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Esqueda, Octavio J. Theological Higher Education in Cuba: A Case Study of the Eastern Cuba Baptist Theological Seminary. Doctor of Philosophy (Higher Education), August 2003, 186 pp., 12 tables, 11 illustrations, references, 130 titles. This research attempted to provide a comprehensive overview of the Eastern Cuba Baptist Theological Seminary within the context of theological education in Cuba and the Cuban Revolution. Three major purposes directed this research. The first one was historical: to document and evaluate the rise, survival and achievements of the Eastern Cuba Baptist Theological Seminary, which has continued its mission through extraordinary political opposition and economical difficulties. The second major purpose was institutional: to gain insight into Cuban seminary modus operandi. The third purpose of the study was to identify perceived needs of the seminary. This study sought to provide information that can facilitate a better understanding of Cuban Christian theological higher education. The Eastern Cuba Baptist Theological Seminary was founded in the city of Santiago the Cuba on October 10, 1949 by the Eastern Baptist Convention. -

Digest : Human Rights in Latin America

H UMAN R IGHTS & H UMAN W ELFARE Human Rights in Latin America Introduction by Regina Nockerts Ph.D. Candidate Graduate School of International Studies, University of Denver As with many regions of the world, human rights are an issue of enduring concern for Latin America. The essays and bibliographies in this digest chart the recent history of human rights issues in this region, beginning, in most cases, with the wave of military coups that began in the 1970s, highlighting their lasting effects on the governments, civil societies, and economies of the region today. The cases of Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru are given here; the Organization of American States (OAS) is also covered. In most countries, the military coups that took place removed democratically elected governments, often because of the fear by national and international elites that the elected officials leaned too far to the Left. This was most evident in the military coup in Chile that ousted (and possibly killed) socialist President Allende. Since then, Chile has emerged with a strengthened democracy, as evidenced by two historic moments in recent events: first, Chile has elected President Michelle Bachelet, the first female Latin American head of state elected on her own merits rather than as the successor to a dead or disabled husband (as was the case with Isabella Peron in Argentina). Second, General Pinochet, who ruled Chile from 1973-1990, and was responsible during that time for the torture and killing of thousands of people, was stripped of his parliamentary immunity and put on trial. -

Afro-Caribbean Religions Helps Form Part of a Wider Cultural and Academic Phenomenon

Introduction eligion is one of the most important elements of Ca rib be an culture that links Afro- Caribbean people to their African past. Scattered over the R three-thousand- mile- long rainbow- shaped archipelago and nestled near the American mainland bordering the beautiful Ca rib be an Sea are living spiri- tual memories and traditions of the African diaspora. A family of religions (big and small, long-standing and recently arrived, defunct and vigorous, ancestral and spiritual) and their peoples dot the unique Ca rib be an map. J. Lorand Matory puts it succinctly: “The Atlantic perimeter hosts a range of groups pro- foundly infl uenced by western African conceptions of personhood and of the divine. Their religions include Candomble, Umbanda, Xango, and Batique in Brazil, as well as Vodou in Haiti and ‘Santeria,’ or Ocha, and Palo Mayombe in Cuba.”1 These diverse religious traditions share several commonalities: They show strong African connections and harbor African cultural memory; they are religions of the people, by and for the people; they are nontraditional and cre- ole faiths shaped by cultures; they are an integral part of the Carib be an colo- nial legacy; and they continue to generate international interest and inspire a huge body of literature worthy of academic study. The robust African religious traditions in the region have muted the voice of academic skeptics who have questioned the ability to prove for certain that African religions survived oppressive conditions of colonialism in the Americas. “A per sis tent white view had been that Africa had little par tic u lar culture to begin with, and that the slaves had lost touch with that as well.”2 The provocative Frazier- Herskovits debate, which has raged since the early 1940s, about how much of African religion and culture survived among African Americans epito- mizes the ripening of the controversy that is almost a century old. -

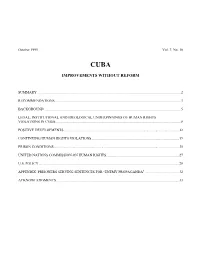

Improvements Without Reform

October 1995 Vol. 7, No. 10 CUBA IMPROVEMENTS WITHOUT REFORM SUMMARY ..............................................................................................................................................................2 RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................................................5 LEGAL, INSTITUTIONAL AND IDEOLOGICAL UNDERPINNINGS OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN CUBA...........................................................................................................................................8 POSITIVE DEVELOPMENTS ...............................................................................................................................12 CONTINUING HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS.................................................................................................19 PRISON CONDITIONS...........................................................................................................................................25 UNITED NATIONS COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS.................................................................................27 U.S. POLICY ...........................................................................................................................................................28 APPENDIX: PRISONERS SERVING SENTENCES FOR AENEMY -

Universal Periodic Review 2009 Cuba

UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW 2009 CUBA NGO: European Centre for Law and Justice 4, Quai Koch 67000 Strasbourg France RELIGIOUS FREEDOM IN CUBA SECTION 1: Legal Framework Notably, in February 2008, Cuba signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. As such, Cuba is now committed by international treaty to respect the religious liberties rights implicated by the right to freedom of expression, association and movement.1 I. Cuban Constitutional Provisions Cuba is still largely considered as a totalitarian state.2 Under Article Eight of the Cuban Constitution, however, the “state recognizes, respects and guarantees freedom of religion. In the Republic of Cuba, religious institutions are separate from the state. The different beliefs and religions enjoy the same consideration.”3 The Constitution also states that religious discrimination “is forbidden and will be punished by law.”4 Article 55 guarantees the individual’s right to change religions, declaring that the state “recognizes, respects and guarantees every citizen’s freedom to change religious beliefs or to not have any, and to profess, within the framework of respect for the law, the religious belief of his preference. The law regulates the state’s relations with religious institutions.”5 Religious freedom in Cuba, however, is subject to the constraints of socialist society. Article 53 explains that “Citizens have freedom of speech and of the press in keeping with the objectives of socialist society.”6 Similarly, Article 62 explicitly states that all freedoms must be exercised within the values of the socialist state: None of the freedoms which are recognized for citizens can be exercised contrary to what is established in the Constitution and by law, or contrary to the existence and objectives of the socialist state, or contrary to the 1 Amnesty International, Cuba Signs Up For Human Rights, (Feb. -

Ibeouuiy Llbrart .; Hatfield

FRINCIPLES AND METHODS INVOLVED IN THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE INDIGENOUS CHURCH IN LATIN AMERICA By THOMAS JAMES CHERRY A.B., Bob Jones College A Thesis Submitted in Fartial Fulf'illment of the Requirements for ; THE D:WREE OF BACHELOR OF SACRED THEOLOGY in The Biblical Seminary in New York New York, N.Y. April 12, 1947 IUBLltl\t 5CUDDL 0~ . iBEOUUiY LlBRARt .; HATfiELD .. PA.. J. TABLE OF COl'iTEN.TS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • .~ • • • • • • • • • • • viii A. The Statement of the Problam ••••••••••••viii B. Definition of Te~ms and Delimitation of the Problem ix 1. Expanded Definition of Term 'Indigenous Church' ix a. Self-supporting Church. • • • • • • • • • x b. Self-propagating Church • • • • • • • • • xi c. Self-governing Church • • • • • • • • • • xi 2. Delimitation of the Problem ••••••••• xii c. Method of Procedure • • • • •••••••••••• xii D. Sources • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • xi v CHAPTER PAGE I. AN HISTORICAL STATEMENT OF THE ERINCIPLE OF THE INDIGENOUS CHURCH IN MISSIONS • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 A. Introduction. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 B. The Indigenous Principle in the New Testament • • • 2 1. Jesus and the Apostles • • • • • • • • • • • • 3 a. Training of the Twelve. • • • • • • • • • 3 b. Evangelization of the Masses ••••••• 3 2. S~aary of Pau1 1 s Practice •••••••••• 4 a. Relationship of Paul to his Converts ••• 5 b. Essential Principles in Method of Paul •• 6 c. Rise of the Indigenous Church Movement ••••••• 8 1. Need for a New Policy. • • • • • ·• • • • • • • 9 a. William Carey1 s Evaluation of a Native Ministry. 9 b. uThe Nevius Planu •••••••••••• 9 1) John L. Nevius' Letter to Home Mission Board. • • • • • • • • • • • 9 2) Results in Korea • • • • • • • • • • 11 c. S.J.W. Clark's Investigation into Missionary Methods. • • • • • • • • • • • 12 1) Resultant Book 11 The Indigenous Churchu. -

Draft Syllabus for Use at Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary

1 DRAFT SYLLABUS FOR USE AT LOUISVILLE PRESBYTERIAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY MISSION IN CONTEXT A JOINT JANUARY TERM COURSE, JANUARY 12-19, 2019 (EM3393) Seminario Evangelico de Matanzas (SET), Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, and Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary (LPTS) Purpose of the Course , The relationship over the years – even when our governments have been most estranged – between the churches and the seminaries in Cuba and the United States has been a great treasure for Christians in both countries and a source of real learning and renewal. It is important to build and continue these relationships with a new generation of church leaders in both countries and to have them shaped by the gifts and realities of the Christian communities in both countries. Toward that end, Louisville and Pittsburgh Seminaries, and Seminario Evangelico de Matanzas will offer in January 2019 an intensive J- term course on Mission in Context for Cuba and the U.S.A. so that our students to study and learn with and from one another. The objectives of this course are to: 1) Explore together our different contexts for mission locally, globally, and historically (perhaps using individual contextual stories and comparing documents for changes in the global context and in the understanding of mission in the past 25 years from the Vatican and the World Council of Churches. [SLO5] 2) Examine together the violent evangelism that began our mission history in this hemisphere and analyze the theological issues that allowed it to happen. To what extent does this persist, in content and-or in method? [SLO 5, 7] 3) Explore the dramatic changes in the context in which we do mission today in Cuba and the U.S.A. -

Nternatlona Etln

Vol. 14, No.1 nternatlona• January 1990 etln• • Forty Years of Missionary Research orty years ago a repatriated missionary from China F launched this journal in New York City as the Occasional Bulletin from the Missionary Research Library. The first issue, a six On Page teen-page mimeographed report, dated March 13, 1950, dealt with a topic that preoccupied many mission analysts: Missions in China. 2 The Legacy of R. Pierce Beaver The present issue of the INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN carries a tribute F. Dean Lueking to our founding editor, R. Pierce Beaver, who died in 1987. F. Dean Lueking, in "The Legacy of R. Pierce Beaver," notes that 6 Mission in the 1990s: Two Views his mentor would be surprised "to learn that his life is a I. Desmond M. Tutu legacy"; but he would nevertheless "be glad for whatever II. Neuza Itioka enhances the mission" of Jesus Christ. 10 Lausanne II and World Evangelization Missionary research continues to be the raison d' etre of the Robert T. Coote INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN. This is especially well reflected in our January issue, with its much-appreciated annual features 14 Noteworthy "Annual Statistical Table on Global Mission: 1990," by David 18 Is Jesus the Son of Allah? B. Barrett, and the editors' selection of "Fifteen Outstanding Graham Kings Books of 1989 for Mission Studies." Readers will also appreciate the continuing series "Mission in the 1990s," with articles by 18 Three Models for Christian Mission Desmond Tutu from South Africa and Neuza Itioka from Brazil. James M. Phillips Associate Editor James M. Phillips offers "Three Models for Christian Mission," identifying basic approaches or stances 26 Annual Statistical Table on Global Mission: that have informed mission through the centuries. -

2016–2017 Catalogue Volume XL 1

Princeton Theological Seminary 2016–2017 Catalogue Volume XL 1. Overview . 3 2. Academic Calendars . 8 2.1 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 Academic Calendar . 9 3. Communication with the Seminary . 14 4. Visiting the Campus . 16 5. Board of Trustees . 17 6. Administration and Professional Staff . 20 7. Faculty . 25 8. Masters-level Programs . 32 8.1 Masters' Application . 33 8.2 Advanced Standing/Transfer Credits . 34 8.3 Mid-year Admissions . 35 8.4 Masters' Admission Requirements . 35 8.5 Non-Degree Students . 36 8.6 Auditing and Auditors . 36 8.7 Unclassified Students . 36 8.8 Academic Advising . 37 8.9 Master of Divinity Program . 37 8.10 Master of Arts in Christian Education and Formation Program . 42 8.11 Master of Divinity/Master of Arts in Christian Education and Formation Dual-degree Program . 48 8.12 Post-MDiv MACEF Program . 48 8.13 Master of Arts (Theological Studies) Program . 48 8.14 Master of Theology Program (advanced master degree) . 52 9. Doctor of Philosophy Program . 54 9.1 PhD Vision Statement . 55 9.2 PhD Learning Goals . 55 9.3 PhD Admission Requirements . 56 9.4 Language Requirements . 56 9.5 PhD Application . 58 9.6 Program of Study . 59 9.7 The Teaching Apprenticeship Program (TAP) . 61 9.8 PhD Seminars at Princeton University . 62 9.9 Areas and Fields of Study . 62 10. Additional Programs and Requirements . 71 10.1 MDiv and MSW Dual Degree Program in Ministry and Social Work . 72 10.2 National Capital Semester for Seminarians (NCSS) . 73 10.3 Presbyterian Exchange Program .