“Notes from the Inside: Building a Center for Feminist Art,” Feminism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Player and the Playing: an Interpretive Study of Richard

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 442 143 CS 510 330 AUTHOR Henry, Mallika TITLE The Player and the Playing: AA Interpretive Study of Richard Courtney's Texts on Learning through Drama. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 411p.; Doctoral dissertation, School of Education, New York University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Doctoral Dissertations (041) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Drama; *Learning Processes; Metaphors; Qualitative Research; *Scholarship ABSTRACT Using qualitative and interpretive methodologies, this dissertation analyzed Richard Courtney's writings to interpret his basic ideas on learning through drama. It focused on later writings (1989, 1990, 1995, 1997) in which Courtney distilled ideas he had been working on for as many as 30 years. It approached Courtney's texts using dramatistic metaphors which concretized his predominantly abstract writings. These metaphors focused on finding the basic elements of a drama: the setting, the act, the actor, and the Other. Through the lenses afforded by these metaphors, the thesis examined Courtney's wide-ranging, eclectic and often imprecise ideas to distill major themes. Courtney used notions like metaphor, symbol, ritual, Being, mind, perspective, oscillation and quaternity with apparently shifting definitions and loosely circumscribed meanings. It collected and analyzed Courtney's meanings recursively, both distilling Courtney's meanings and expanding them through concrete hypothetical examples. Courtney wrote about drama in abstract terms, using notions he had garnered from other disciplines to describe the process of learning through drama. The final construction that emerged in this dissertation represents the experience of the actor/learner: it is concentric, radiating from a nub which represents the feelings and imagination of the actor. -

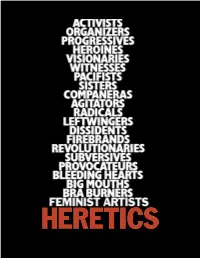

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Mapping Robert Storr

Mapping Robert Storr Author Storr, Robert Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams ISBN 0870701215, 0810961407 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/436 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art bk 99 £ 05?'^ £ t***>rij tuin .' tTTTTl.l-H7—1 gm*: \KN^ ( Ciji rsjn rr &n^ u *Trr» 4 ^ 4 figS w A £ MoMA Mapping Robert Storr THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK (4 refuse Published in conjunction with the exhibition Mappingat The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 6— tfoti h December 20, 1994, organized by Robert Storr, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture The exhibition is supported by AT&TNEW ART/NEW VISIONS. Additional funding is provided by the Contemporary Exhibition Fund of The Museum of Modern Art, established with gifts from Lily Auchincloss, Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and Mr. and Mrs. Ronald S. Lauder. This publication is supported in part by a grant from The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. Produced by the Department of Publications The Museum of Modern Art, New York Osa Brown, Director of Publications Edited by Alexandra Bonfante-Warren Designed by Jean Garrett Production by Marc Sapir Printed by Hull Printing Bound by Mueller Trade Bindery Copyright © 1994 by The Museum of Modern Art, New York Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited in the Photograph Credits. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1995 ARTIST'S CHOICE: ELIZABETH MURRAY June 20 - August 22, 1995 An exhibition conceived and installed by American artist Elizabeth Murray is the fifth in The Museum of Modern Art's series of ARTIST'S CHOICE exhibitions. On view from June 20 to August 22, 1995, ARTIST'S CHOICE: ELIZABETH MURRAY presents more than 100 drawings, paintings, prints, and sculptures by approximately seventy women artists. The exhibition involves works created between 1914 and 1973, including those ranging from early modernists Frida Kahlo and Liubov Popova to contemporary artists Nancy Graves and Dorothea Rockburne. Murray focuses particular attention on artists who made their reputations during the 1950s and 1960s, such as Lee Bontecou, Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell, when Murray herself was studying and forming her style. This exhibition and the accompanying video and panel discussion are made possible by a generous grant from The Charles A. Dana Foundation. Organized in collaboration with Kirk Varnedoe, Chief Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, the ARTIST'S CHOICE series invites artists to create an exhibition from the Museum's collection according to a personally chosen theme or principle. "I wanted, for myself, to explore what being a woman in the art world has meant," Murray writes in the exhibition brochure. "I wanted to weave together a sense of the genuine and profound contribution women's work has made to the art of our time." - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Fax: 212-708-9889 2 Installed in the Museum's third-floor contemporary painting and sculpture galleries, the exhibition is arranged in thematic groupings. -

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930S-2007, Bulk 1960-1990

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930s-2007, bulk 1960s-1990, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie L. Ashley and Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 May Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1960s-circa 1980s........................................ 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1950s-2006.................................................................. 7 Series 3: Writings, 1930s-1990s........................................................................... -

Download Artist's CV

I N M A N G A L L E R Y Michael Jones McKean b. 1976, Truk Island, Micronesia Lives and works in New York City, NY and Richmond, VA Education 2002 MFA, Alfred University, Alfred, New York 2000 BFA, Marywood University, Scranton, Pennsylvania Solo Exhibitions 2018-29 (in progress) Twelve Earths, 12 global sites, w/ Fathomers, Los Angeles, CA 2019 The Commune, SuPerDutchess, New York, New York The Raw Morphology, A + B Gallery, Brescia, Italy 2018 UNTMLY MLDS, Art Brussels, Discovery Section, 2017 The Ground, The ContemPorary, Baltimore, MD Proxima Centauri b. Gleise 667 Cc. Kepler-442b. Wolf 1061c. Kepler-1229b. Kapteyn b. Kepler-186f. GJ 273b. TRAPPIST-1e., Galerie Escougnou-Cetraro, Paris, France 2016 Rivers, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA Michael Jones McKean: The Ground, The ContemPorary Museum, Baltimore, MD The Drift, Pittsburgh, PA 2015 a hundred twenty six billion acres, Inman Gallery, Houston, TX three carbon tons, (two-person w/ Jered Sprecher) Zeitgeist Gallery, Nashville, TN 2014 we float above to spit and sing, Emerson Dorsch, Miami, FL Michael Jones McKean and Gilad Efrat, Inman Gallery, at UNTITLED, Miami, FL 2013 The Religion, The Fosdick-Nelson Gallery, Alfred University, Alfred, NY Seven Sculptures, (two person show with Jackie Gendel), Horton Gallery, New York, NY Love and Resources (two person show with Timur Si-Qin), Favorite Goods, Los Angeles, CA 2012 circles become spheres, Gentili APri, Berlin, Germany Certain Principles of Light and Shapes Between Forms, Bernis Center for ContemPorary Art, Omaha, NE -

Cartographic Perspectives Information Society 1

Number 53, Winterjournal 2006 of the Northcartographic American Cartographic perspectives Information Society 1 cartographic perspectives Number 53, Winter 2006 in this issue Letter from the Editor INTRODUCTION Art and Mapping: An Introduction 4 Denis Cosgrove Dear Members of NACIS, FEATURED ARTICLES Welcome to CP53, the first issue of Map Art 5 Cartographic Perspectives in 2006. I Denis Wood plan to be brief with my column as there is plenty to read on the fol- Interpreting Map Art with a Perspective Learned from 15 lowing pages. This is an important J.M. Blaut issue on Art and Cartography that Dalia Varanka was spearheaded about a year ago by Denis Wood and John Krygier. Art-Machines, Body-Ovens and Map-Recipes: Entries for a 24 It’s importance lies in the fact that Psychogeographic Dictionary nothing like this has ever been kanarinka published in an academic journal. Ever. To punctuate it’s importance, Jake Barton’s Performance Maps: An Essay 41 let me share a view of one of the John Krygier reviewers of this volume: CARTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES …publish these articles. Nothing Cartographic Design on Maine’s Appalachian Trail 51 more, nothing less. Publish them. Michael Hermann and Eugene Carpentier III They are exciting. They are interest- ing: they stimulate thought! …They CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS are the first essays I’ve read (other Illinois Historical Aerial Photography Digital Archive Keeps 56 than exhibition catalogs) that actu- Growing ally try — and succeed — to come to Arlyn Booth and Tom Huber terms with the intersections of maps and art, that replace the old formula REVIEWS of maps in/as art, art in/as maps by Historical Atlas of Central America 58 Reviewed by Mary L. -

History of Encaustic

THE HISTORY OF ENCAUSTIC Wax is an excellent preservative of materials. The Greeks applied coatings of wax and pitch to weatherproof their ships. Pigmenting the wax gave rise to the decorating of warships and merchant ships. The use of a rudimentary encaustic was an established practice in the Classical Period (500-323 BC). It is possible that at about that time the crude paint applied with tar brushes to the ships was refined for the art of painting on panels. ENCAUSTIC AND TEMPERA Encaustic on panels rivaled that of tempera in what are the earliest known portable easel paintings. Tempera was a faster, cheaper process. Encaustic was a slow involved technique, but the paint could be built up in relief, and the wax gave a rich optical effect to the pigment. These characteristics made the finished work startlingly lifelike. Moreover, encaustic had far greater durability than tempera, which was vulnerable to moisture. Pliny refers to encaustic paintings several hundred years old in the possession of Roman aristocrats of his own time. ENCAUSTIC IN SCULPTURE We know that the white marble we see today in the monuments of Greek antiquity was once colored, either boldly or delicately and that wax was used to both preserve and enhance that marble (see "Polychromy in Greek Sculpture" below). The literary evidence of how this was done is scant. The figures on the Alexander Sarcophagus in the archeological Museum of Istanbul are an example of such coloration, although it is not clear how intense the original color was. The methods used to color the marble probably varied. -

Hauser & Wirth Announces Major Initiative to Raise Funds for Key

Press Release Hauser & Wirth Announces Major Initiative to Raise Funds for Key Visual Arts Organizations in New York City Impacted by the COVID-19 Pandemic Beginning early October, works by scores of artists will be sold to benefit 16 non-profit institutions and charitable partners New York…Hauser & Wirth co-presidents Iwan Wirth, Manuela Wirth, and Marc Payot, announced today that the gallery has organized ‘Artists for New York,’ a major initiative to raise funds in support of a group of pioneering non-profit visual arts organizations across New York City that have been profoundly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The project brings together dozens of works committed by foremost artists across generations, from both within and outside of the gallery’s program, that will be sold to benefit these institutions that have played a significant role in shaping the city’s rich cultural history and will play a critical role in its future recovery. The coronavirus pandemic has taken an unprecedented toll upon the arts in New York. Facing dire budget shortfalls for the 2020 fiscal year caused by necessary and prolonged closures during the pandemic, and expecting further impact upon earned income and contributed revenue in the year ahead, the city’s small and mid-scale institutions are extremely vulnerable at this moment. ‘Artists for New York’ will raise funds to support the recovery needs of fourteen of these organizations: Artists Space, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Dia Art Foundation, The Drawing Center, El Museo del Barrio, High Line Art, MoMA PS1, New Museum, Public Art Fund, Queens Museum, SculptureCenter, The Studio Museum in Harlem, Swiss Institute, and White Columns. -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

Ida Applebroog

ronald ſeldman gallery IDA APPLEBROOG Born: Bronx, New York, 1929 New York Institute of Applied Arts and Sciences, 1948-50 School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 1965-68 SELECTED INDIVIDUAL EXHIBITIONS 2011 Hauser & Wirth London, ‘Ida Applebroog’, London, England 2010 Hauser & Wirth New York, ‘Monalisa’, New York NY 2009 Nathalie Parienté, ‘Ida Applebroog: l’histoire par la fenêtre’, Paris, France 2007 Rowland Contemporary, ‘Photogenetics’, Chicago IL 2005 Ronald Feldman Fine Arts Booth, ‘The Armory Show’, New York NY2002 Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, NY, Modern Olympia, January 12-February 9. 2001 Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, NY, Galileo Works, April 28-June 2. 2000 Galerie Nathalie Pariente, Paris, France, Works on paper from the 1980s, November 16-December 20. 1999 Lowe Gallery, Atlanta, GA, Ida Applebroog, January 8-29. 1998 Galerie Nathalie Pariente, Paris, France. The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts/Museum of American Art, Philadelphia, PA. 1997 Modernism, San Francisco, CA. Barbara Gross Galerie, Munich, Germany. 1996 Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, NY. 1994 Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, NY. Freedman Gallery, Center for the Arts, Albright College, Reading, PA. Sarah Moody Gallery of Art, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL. 1993 The Weatherspoon Gallery, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC. (catalogue) The Metropolitan Museum Mezzanine Gallery, New York. Gallery Paule Anglim, San Francisco. Orchard Gallery, Derry, Ireland, and travel to the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland, Cubitt Street, London. (catalogue) Brooklyn Museum, New York. Frith Street Gallery, London. 1992 Kunsthallen Brandts Klaedefabrik, Odense, Denmark. RealistmusStudio, Berlin, Germany. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216