The Dynamics of Sango Language Spread. by Mark Karan. Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steps Toward a Grammar Embedded in Data Nicholas Thieberger

Steps toward a grammar embedded in data Nicholas Thieberger 1. Introduction 1 Inasmuch as a documentary grammar of a language can be characterized – given the formative nature of the discussion of documentary linguistics (cf. Himmelmann 1998, 2008) – part of it has to be based in the relationship of the analysis to the recorded data, both in the process of conducting the analysis with interactive access to primary recordings and in the presenta- tion of the grammar with references to those recordings. This chapter discusses the method developed for building a corpus of recordings and time-aligned transcripts, and embedding the analysis in that data. Given that the art of grammar writing has received detailed treatment in two recent volumes (Payne and Weber 2006, Ameka, Dench, and Evans 2006), this chapter focuses on the methodology we can bring to developing a grammar embedded in data in the course of language documentation, observing what methods are currently available, and how we can envisage a grammar of the future. The process described here creates archival versions of the primary data while allowing the final work to include playable versions of example sen- tences, in keeping with the understanding that it is our professional respon- sibility to provide the data on which our claims are based. In this way we are shifting the authority of the analysis, which traditionally has been lo- cated only in the linguist’s work, and acknowledging that other analyses are possible using new technologies. The approach discussed in this chap- ter has three main benefits: first, it gives a linguist the means to interact instantly with digital versions of the primary data, indexed by transcripts; second, it allows readers of grammars or other analytical works to verify claims made by access to contextualised primary data (and not just the limited set of data usually presented in a grammar); third, it provides an archival form of the data which can be accessed by speakers of the lan- guage. -

LACITO - Laboratoire De Langues & Civilisations À Tradition Orale Rapport Hcéres

LACITO - Laboratoire de langues & civilisations à tradition orale Rapport Hcéres To cite this version: Rapport d’évaluation d’une entité de recherche. LACITO - Laboratoire de langues & civilisations à tradition orale. 2018, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3, Centre national de la recherche scien- tifique - CNRS, Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales - INALCO. hceres-02031755 HAL Id: hceres-02031755 https://hal-hceres.archives-ouvertes.fr/hceres-02031755 Submitted on 20 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Research evaluation REPORT ON THE RESEARCH UNIT: Langues et Civilisations à Tradition Orale LaCiTO UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF THE FOLLOWING INSTITUTIONS AND RESEARCH BODIES: Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3 Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales – INALCO Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique – CNRS EVALUATION CAMPAIGN 2017-2018 GROUP D In the name of Hcéres1 : In the name of the experts committees2 : Michel Cosnard, President Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Chairman of the committee Under the decree No.2014-1365 dated 14 november 2014, 1 The president of HCERES "countersigns the evaluation reports set up by the experts committees and signed by their chairman." (Article 8, paragraph 5) ; 2 The evaluation reports "are signed by the chairman of the expert committee". -

On Adaptation in Military Operations: Tinkering and Bottom–Up Perspectives

AARMS Vol. 13, No. 3 (2014) 389–396. On Adaptation in Military Operations: Tinkering and Bottom–Up Perspectives 1 JOBBÁGY Zoltán A biological perspective has much to offer for a better understanding of military operations. Biological evolution and military operations feature perpetual novelty and conditions far from equilibrium featuring dynamics that demand continuous adaptation. The author suggests that comprehending military operations in an evo- lutionary framework requires a shift from mechanics and engineering to biology and adaptation. Thus the emphasis moves from statics to dynamics, from time–free to time–prone reality, from determinism to probability and chance, and from uni- formity to variation and diversity, with all the consequences. Introduction A biological perspective on human behaviour has much to offer for a better understanding of the relationship between co-operation and conflict. Regardless whether one sees war and military operations through the eyes of Clausewitz, approach it as a complex adaptive sys- tem, or examine it along attributes that display similarities with biological evolution, there are timeless and innate characteristics. It is not difficult to conclude that both biological evolution and military operations are intrinsically complex, and primordial violence is at the heart of both. [1] Military operations indeed can be understood as a complex adaptive system in which the system properties emerge from the interactions of the many components at lower levels. The abundance of dispersed interactions in military operations indicates a mechanism that often lacks global control, but feeds from cross–cutting hierarchical setup. Similar to biolog- ical evolution, military operations also feature perpetual novelty and far from equilibrium dynamics that demand continual adaptation. -

Colloque International Backing / Base Articulatoire Arrière

Colloque International Backing / Base Articulatoire Arrière du 2 au 4 mai 2012 Lieu/Place : Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3, E MAISON DE LA RECHERCHE, 4 RUE DES IRLANDAIS, PARIS 5 (RER B – LUXEMBOURG) Organisateurs : Jean Léo Léonard (LPP, UMR 7018 Paris 3), Samia Naïm (LACITO, UMR 7107, associé à Paris 3), Antonella Gaillard-Corvaglia (LPP, UMR 7018 Paris 3) Pour toute information concernant l’hébergement vous pouvez consulter le site de l’hôtel Senlis : http://www.paris-hotel-senlis.com/ Pourquoi il n'y a pas de pharyngalisation ? Jean-Pierre Angoujard (LLING - Université de Nantes) Si les études sur les consonnes pharyngalisées de l'arabe (les « emphatiques ») ont porté sur la nature de ces consonnes et de l'articulation secondaire qui leur est associée, elles ont plus souvent débattu des effets de coarticulation, c'est-à-dire de la célèbre « diffusion de l'emphase ». A côté de travaux essentiels comme ceux de S. Ghazeli (1977, 1981), la phonologie générative et ses récentes variantes optimales ont suscité de nombreux débats sur cette « diffusion » (types de règles, itération, extension du domaine etc.). L'ensemble de cette littérature sur la « diffusion de l'emphase » (et spécifiquement l'interprétation du terme « pharyngalisation ») a souffert d'une confusion entre, d'une part la reconnaissance des effets de coarticulation et, d'autre part, les descriptions par règles de réécriture ou par contraintes de propagation (spread). Nous montrerons, dans un cadre purement déclaratif (Bird 1995, Angoujard 2006), que la présence de segments pharyngalisés (que l'on peut désigner, pour simplifier, comme non « lexicaux ») n'implique aucun processus modificateur (insertion, réécriture). -

Repupublic of Congo

BE TOU & IMPFONDO MARKET ASSESSMENT IN LIKOUALA – REPUBLIC OF CONGO Cash Based Transfer Market This market assessment assesses the feasibility of markets in Bétou and Assessment: Impfondo to absorb and respond to a CBT intervention aimed at supporting CAR refugees’ food security in The Republic of Congo’s Likouala region. The December report explores appropriate measures a CBT intervention in Likouala would 2015 need to adopt in order to address hurdles limiting Bétou and Impfondo markets’ functionality. Contents Executive Summary: ............................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Introduction and Macro-Economic Analysis of RoC .............................................................. 5 1.1: Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2: The Economy ................................................................................................................................... 6 Section 2: Market Assessment Introduction and Methodology ............................................................. 9 2.1: Market Assessment Introduction .................................................................................................... 9 2.2: Market Assessment Methodology ................................................................................................... 9 Section 3: Limitations of the Market Assessment ............................................................................... -

Dissolved Major Elements Exported by the Congo and the Ubangui Rivers

Journal of Hydrology, 135 (1992) 237-257 237 Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam [21 Dissolved major elements exported by the Congo and the Ubangi rivers during the period 1987-1989 Jean-Luc Probst a, Renard-Roger NKounkou ~', G6rard Krempp ~, Jean-Pierre Bricquet b, Jean-Pierre Thi6baux c and Jean-Claude Olivry d ~Centre de G~ochimie de ia Surface (CNRS), I. rue Blessig, 67084 Strasbourg Cedex, France bCentre ORSTOM, B.P. 181, Brazzaville, Congo ~Centre ORSTOM. B.P. 893, Bangui. Central dfrican Republic OCentre ORSTOM, B.P. 2528. Bamako. Mali (Received 20 September 1991; accepted 6 October 1991) ABSTRACT Probst, J.-L., NKounkou, R.-R., Krempp, G., Bricquet, J.-P., Thi6baux, J.-P. and Olivry, J.-C., 1992. Dissolved major elements exported by the Congo and the Ubangi rivers during the period 1987-1989. J. Hydrol., 135: 237-257. On the basis of monthly sampling during the period 1987-1989, the geochemis:ry of ~he Congo and the Ubangi (second largest tributary of the Congo) rivers was studied in order (I) to understand the seasonal variations of the physico-chemical parameters of the waters and (2) to estimate the annual dissolved fluxes exported by the two rivers. The results presented here correspond to the first three years of measurements carried out for a scientific programme (Interdisciplinary Research Programme on Geodynamics of Peri- Atlantic lntertropical Environments, Operation 'Large River Basins' (PIRAT-GBF) undertaken jointly by lnstitut National des Sciences de l'Univers (INSU) and Institut Fran~ais de Recherche Scientifique pour ie D6veloppement en Coop6ration (ORSTOM)) planned to run for at least ten years. -

Frustrations of the Documentary Linguist: the State of the Art in Digital Language Archiving and the Archive That Wasnâ•Žt

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Department of Spanish Research Spanish 2006 Frustrations of the Documentary Linguist: The State of the Art in Digital Language Archiving and the Archive that Wasn’t Robert E. Vann [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/spanish_research Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Vann, Robert E., "Frustrations of the Documentary Linguist: The State of the Art in Digital Language Archiving and the Archive that Wasn’t" (2006). Department of Spanish Research. 1. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/spanish_research/1 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Spanish at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Spanish Research by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frustrations of the documentary linguist: The state of the art in digital language archiving and the archive that wasn’t Robert E. Vann Western Michigan University 1.0 Introduction This paper is a qualitative review and critique of existing electronic language archives from the perspective of the documentary linguist. In today’s day and age there are many online archives available for storage of and access to digital language data, among others: AILLA, ANLC, ASEDA, DOBES, ELRA, E-MELD, LACITO, LDC, LPCA, OTA, PARADISEC, Rosetta, SAA, THDL, and UHLCS. It is worth pointing out that I use the term language archive loosely in this paper, referring to a variety of organizations and resources such as those listed above that store and provide digital language data to different degrees and for different purposes. -

THE DOUBLE-FRANKING PERIOD ALSACE-LORRAINE, 1871-1872 by Ruth and Gardner Brown

WHOLE NUMBER 199 (Vol. 41, No.1) January 1985 USPS #207700 THE DOUBLE-FRANKING PERIOD ALSACE-LORRAINE, 1871-1872 By Ruth and Gardner Brown Introduction Ruth and I began this survey in December 1983 and 1 wrote the art:de in November] 984 after her sudden death in July. I have included her narre as an author since she helped with the work. 1 have used the singular pro noun in this article because it is painful for me to do otherwise. After buying double-franking covers for over 30 years I recently made a collection (an exhibit) out of my accumulation. In anticipation of this ef fort, about 10 years ago, I joined the Societe Philatelique Alsace-Lorraine (SPAL). Their publications are to be measured not in the number of pages but by weight! Over the years I have received 11 pounds of documents, most of it is xeroxed but in 1983 they issued a nicely printed, up to date catalogue covering the period 1872-1924. Although it is for the time frame after the double-franking era, it is the only source known to me which solves the mys teries of the name changes of French towns to German. The ones which gave me the most trouble were French: Thionville, became German Dieden l!{\fen, and Massevaux became Masmunster. One of the imaginative things done by SPAL was to offel' reduced xerox copies of 40, sixteen-page frames, exhibited at Colmar in 1974. Many of these covered the double-franking period. Before mounting my collection I decided to review the SPAL literature to get a feeling for what is common and what is rare. -

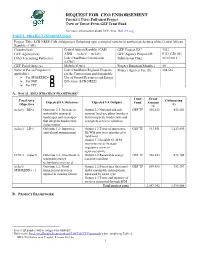

REQUEST for CEO ENDORSEMENT PROJECT TYPE: Full-Sized Project TYPE of TRUST FUND:GEF Trust Fund

REQUEST FOR CEO ENDORSEMENT PROJECT TYPE: Full-sized Project TYPE OF TRUST FUND:GEF Trust Fund For more information about GEF, visit TheGEF.org PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Project Title: LCB-NREE CAR child project: Enhancing agro-ecological systems in northern prefectures of the Central African Republic (CAR) Country(ies): Central African Republic (CAR) GEF Project ID:1 9532 GEF Agency(ies): AfDB (select) (select) GEF Agency Project ID: P-Z1-CZ0-001 Other Executing Partner(s): Lake Chad Basin Commission Submission Date: 06/16/2016 (LCBC) GEF Focal Area (s): Multifocal Area Project Duration(Months) 60 Name of Parent Program (if Lake Chad Basin Regional Program Project Agency Fee ($): 204,636 applicable): for the Conservation and Sustainable For SFM/REDD+ Use of Natural Resources and Energy For SGP Efficiency (LCB-NREE) For PPP A. FOCAL AREA STRATEGY FRAMEWORK2 Trust Grant Focal Area Cofinancing Expected FA Outcomes Expected FA Outputs Fund Amount Objectives ($) ($) (select) BD-2 Outcome 2.1: Increase in Output 2.2 National and sub- GEF TF 502,453 855,203 sustainably managed national land-use plans (number) landscapes and seascapes that incorporate biodiversity and that integrate biodiversity ecosystem services valuation conservation (select) LD-1 Outcome 1.2: Improved Output 1.2 Types of innovative GEF TF 913,551 1,113,890 agricultural management SL/WM practices introduced at field level Output 1.3 Suitable SL/WM interventions to increase vegetative cover in agroecosystems CCM-3 (select) Outcome 3.2: Investment in Output 3.2 Renewable energy GEF TF 502,453 672,100 renewable energy capacity installed technologies increased (select) Outcome 1.2: Good Output 1.2 Forest area (hectares) GEF TF 639,485 753,307 SFM/REDD+ - 1 management practices under sustainable management, applied in existing forests separated by forest type Output 1.3 Types and quantity of services generated through SFM Total project costs 2,557,942 3,394,500 B. -

Sociolinguistic Situation of Kurdish in Turkey: Sociopolitical Factors and Language Use Patterns

DOI 10.1515/ijsl-2012-0053 IJSL 2012; 217: 151 – 180 Ergin Öpengin Sociolinguistic situation of Kurdish in Turkey: Sociopolitical factors and language use patterns Abstract: This article aims at exploring the minority status of Kurdish language in Turkey. It asks two main questions: (1) In what ways have state policies and socio- historical conditions influenced the evolution of linguistic behavior of Kurdish speakers? (2) What are the mechanisms through which language maintenance versus language shift tendencies operate in the speech community? The article discusses the objective dimensions of the language situation in the Kurdish re- gion of Turkey. It then presents an account of daily language practices and perceptions of Kurdish speakers. It shows that language use and choice are sig- nificantly related to variables such as age, gender, education level, rural versus urban dwelling and the overall socio-cultural and political contexts of such uses and choices. The article further indicates that although the general tendency is to follow the functional separation of languages, the language situation in this con- text is not an example of stable diglossia, as Turkish exerts its increasing pres- ence in low domains whereas Kurdish, by contrast, has started to infringe into high domains like media and institutions. The article concludes that the preva- lent community bilingualism evolves to the detriment of Kurdish, leading to a shift-oriented linguistic situation for Kurdish. Keywords: Kurdish; Turkey; diglossia; language maintenance; language shift Ergin Öpengin: Lacito CNRS, Université Paris III & Bamberg University. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction Kurdish in Turkey is the language of a large population of about 15–20 million speakers. -

Discharge of the Congo River Estimated from Satellite Measurements

Discharge of the Congo River Estimated from Satellite Measurements Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science Degree At The Ohio State University By Lisa Schaller The Ohio State University Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………..….....Page iii List of Figures ………………………………………………………………...……….....Page iv Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….....Page 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………….....Page 2 Study Area ……………………………………………………………..……………….....Page 3 Geology………………………………………………………………………………….....Page 5 Satellite Data……………………………………………....…………………………….....Page 6 SRTM ………………………………………………………...………………….....Page 6 HydroSHEDS ……………………………………………………………….….....Page 7 GRFM ……………………………………………………………………..…….....Page 8 Methods ……………………………………………………………………………..….....Page 9 Elevation ………………………………………………………………….…….....Page 9 Slopes ………………………………………………………………………….....Page 10 Width …………………………………………….…………………………….....Page 12 Manning’s n ……………………………………………………………..…….....Page 14 Depths ……………………………………………………………………...….....Page 14 Discussion ………………………………………………………………….………….....Page 15 References ……………………………….…………………………………………….....Page 18 Figures …………………………………………………………………………...…….....Page 20 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank OSU’s Climate, Water and Carbon program for their generous support of my research project. I would also like to thank NASA’s programs in Terrestrial Hydrology and in Physical Oceanography for support and data. Without Doug Alsdorf and Michael Durand, this project would -

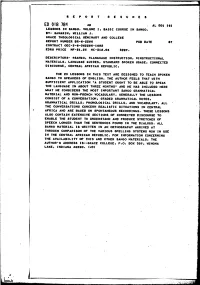

Lessons in Sango. Volume I, Basic Course in Sango. By- Samarin, William J

REPORT RESUMES 46 ED 018 784 . AL 001 161 LESSONS IN SANGO. VOLUME I, BASIC COURSE IN SANGO. BY- SAMARIN, WILLIAM J. GRACE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY AND COLLEGE REPORT NUMBER BR -6 -2286 PUB DATE 67 CONTRACT OEC36062286..1662 MS PRICE mr-s1.25 HC- $12.96 322P. DESCRIPTORS- * SANGO, *LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION, *INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS, LANGUAGE GUIDES, STANDARD SPOKEN USAGE,CONNECTED DISCOURSE, CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, THE 25 LESSONS IN THIS TEXT ARE DESIGNED TO TEACH SPOKEN SANGO TO SPEAKERS OF ENGLISH. THE AUTHOR FEELS THAT WITH SUFFICIENT APPLICATION "A STUDENT OUGHT TO BE ABLE7.(;) SPEAK THE LANGUAGE IN ABOUT THREE MONTHS" AND HE HAS INCLUDEDHERE WHAT. HE CONSIDERS THE MOST IMPORTANT SANGO GRAMMATICAL MATERIAL AND NON - FRENCH VOCABULARY. GENERALLY THELESSONS CONSIST OF A CONVERSATION, GRADED GRAMMATICAL NOTES, GRAMMATICAL DRILLS, PHONOLOGICAL DRILLS, AND VOCABULARY. ALL THE CONVERSATIONS CONCERN REALISTIC SITUATIONS INCENTRAL AFRICA AND ARE BASED ON SPONTANEOUS RECORDINGS. THESELESSONS ALSO CONTAIN EXTENSIVE SECTIONS OF CONNECTED DISCOURSE TO ENABLE THE STUDENT TO UNDERSTAND AND PRODUCE STRETCHES OF SPEECHLONGER THAN THE SENTENCES FOUND IN THE DIALOGS.ALL SANGO MATERIAL IS WRITTEN IN AN ORTHOGRAPHY ARRIVED AT THROUGH COMPARISON OF THE VARIOUS SPELLING SYSTEMS NOW IN USE IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC. FOR INFORMATIONCONCERNING THE AVAILABILITY OF THIS AND OTHER SANGO MATERIALS, THE AUTHOR'S ADDRESS IS- -GRACE COLLEGE, P.O. BOX 397, WINONA LAKE, INDIANA 46590. (JD) ,- ?.4. ?ER Ve.' LESSONS IN SANGO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION -& WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION ;POSITION OR POLICY.