The Wild Cascades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Cascades Contested Terrain

North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History CONTESTED TERRAIN: North Cascades National Park Service Complex, Washington An Administrative History By David Louter 1998 National Park Service Seattle, Washington TABLE OF CONTENTS adhi/index.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-1999 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/[11/22/2013 1:57:33 PM] North Cascades NP: Contested Terrain: North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History (Table of Contents) NORTH CASCADES Contested Terrain North Cascades National Park Service Complex: An Administrative History TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Cover: The Southern Pickett Range, 1963. (Courtesy of North Cascades National Park) Introduction Part I A Wilderness Park (1890s to 1968) Chapter 1 Contested Terrain: The Establishment of North Cascades National Park Part II The Making of a New Park (1968 to 1978) Chapter 2 Administration Chapter 3 Visitor Use and Development Chapter 4 Concessions Chapter 5 Wilderness Proposals and Backcountry Management Chapter 6 Research and Resource Management Chapter 7 Dam Dilemma: North Cascades National Park and the High Ross Dam Controversy Chapter 8 Stehekin: Land of Freedom and Want Part III The Wilderness Park Ideal and the Challenge of Traditional Park Management (1978 to 1998) Chapter 9 Administration Chapter 10 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/noca/adhi/contents.htm[11/22/2013 -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Cascades Butterfly Project North Cascades National Park Resource Brief - 2011

CASCADES BUTTERFLY PROJECT NORTH CASCADES NATIONAL PARK RESOURCE BRIEF - 2011 Cascades Butterfly Project Climate change is expected to affect mountain ecosystems in many ways. Scientists predict that warmer summers may result in earlier snowmelt, more frequent forest fires, and changes in distributions of plants and animals. Although some ecosystem changes have already been observed, (e.g. melting glaciers), many future impacts remain uncertain. Monitoring provides a way to document ecosystem changes, anticipate future changes, and improve management of protected lands. Butterflies are sensitive indicators of butterflies are able to fly to higher eleva- climate change because temperature tions in response to warming tempera- influences the timing of an individual’s tures, will they be able to establish as life cycle and the geographic distribu- breeding residents? Will host plants be tion of species. As individuals develop able to migrate up quickly enough to from egg to larvae to pupae and finally support butterfly populations, or will to mature butterfly, temperature thresh- some species become extinct? olds may trigger these changes. Annual temperature patterns are often the What are we doing? primary determinant of the distribution Six protected areas in the Cascade of “generalist” butterflies. Generalist Mountains are establishing a program butterflies are species that can utilize to monitor butterflies to learn how cli- many different plant species for nectar, mate is affecting their populations. The larval development, and egg deposition. six areas include four sites in Washing- Specialist butterflies depend on a few ton: North Cascades National Park, plant species for food and development Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National and they can be directly and indirectly Forest, Okanagan-Wenatchee National influenced by climate (temperature and Forest, and Mount Rainier National precipitation). -

Snowmobiles in the Wilderness

Snowmobiles in the Wilderness: You can help W a s h i n g t o n S t a t e P a r k s A necessary prohibition Join us in safeguarding winter recreation: Each year, more and more people are riding snowmobiles • When riding in a new area, obtain a map. into designated Wilderness areas, which is a concern for • Familiarize yourself with Wilderness land managers, the public and many snowmobile groups. boundaries, and don’t cross them. This may be happening for a variety of reasons: many • Carry the message to clubs, groups and friends. snowmobilers may not know where the Wilderness boundaries are or may not realize the area is closed. For more information about snowmobiling opportunities or Wilderness areas, please contact: Wilderness…a special place Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (360) 902-8500 Established by Congress through the Wilderness Washington State Snowmobile Association (800) 784-9772 Act of 1964, “Wilderness” is a special land designation North Cascades National Park (360) 854-7245 within national forests and certain other federal lands. Colville National Forest (509) 684-7000 These areas were designated so that an untouched Gifford Pinchot National Forest (360) 891-5000 area of our wild lands could be maintained in a natural Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest (425) 783-6000 state. Also, they were set aside as places where people Mt. Rainier National Park (877) 270-7155 could get away from the sights and sounds of modern Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest (509) 664-9200 civilization and where elements of our cultural history Olympic National Forest (360) 956-2402 could be preserved. -

Welcome to Neverland! I Hope Each of You Are As Excited As I Am to Embark on a New Grand Year. This Year, I Encourage Everyone T

Welcome to Neverland! I hope each of you In August, I began the second semester of my are as excited as I am to embark on a new Grand senior year at UTC and I am year. This year, I encourage everyone to chase anxiously countng down the their dreams through hard work and dedicaton. days. Right now, I am taking Though the 2020-2021 term may look a litle microbiology, plant morpholo- diferent than normal, that just means we’ll gy, and physics; so far I have need to get creatve! Even a global pandemic learned that I do not care for plants. I have al- can’t stop Rainbow Girls. ready submited my vet school applicatons to a variety of schools and, hopefully, I will hear some- During the quarantne, I have been busier thing by February! I have an interview already than ever! I work as a nurse at an animal ER on scheduled for UTK so wish me luck! the weekends; afer COVID hit, I began working full tme because our clinic was overwhelmed with cases. Thankful- I hope each of you are staying healthy and safe during ly, I work with a great group of people so the added hours these uncertain tmes. Though we cannot have our weren’t too bad. Even though I have been able to cut back typical fall events, I hope to be back to ofcial visits in to part-tme again, you can stll fnd me in the ICU Friday no tme! My thoughts are with you and always remem- through Sunday doing what I love and treatng patents. -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe

1 Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe: Traditional Resource Harvest Sites West of the Crest of the Cascades Mountains in Washington State and below the Cascades of the Columbia River Eugene Hunn Department of Anthropology Box 353100 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-3100 [email protected] for State of Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife WDFW contract # 38030449 preliminary draft October 11, 2003 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 5 Map 1 5f 1. Goals and scope of this report 6 2. Defining the relevant Indian groups 7 2.1. How Sahaptin names for Indian groups are formed 7 2.2. The Yakama Nation 8 Table 1: Yakama signatory tribes and bands 8 Table 2: Yakama headmen and chiefs 8-9 2.3. Who are the ―Klickitat‖? 10 2.4. Who are the ―Cascade Indians‖? 11 2.5. Who are the ―Cowlitz‖/Taitnapam? 11 2.6. The Plateau/Northwest Coast cultural divide: Treaty lines versus cultural 12 divides 2.6.1. The Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast versus 13 Plateau 2.7. Conclusions 14 3. Historical questions 15 3.1. A brief summary of early Euroamerican influences in the region 15 3.2. How did Sahaptin-speakers end up west of the Cascade crest? 17 Map 2 18f 3.3. James Teit‘s hypothesis 18 3.4. Melville Jacobs‘s counter argument 19 4. The Taitnapam 21 4.1. Taitnapam sources 21 4.2. Taitnapam affiliations 22 4.3. Taitnapam territory 23 4.3.1. Jim Yoke and Lewy Costima on Taitnapam territory 24 4.4. -

A. Forbes Mackay 1908-1909 Dr

The Diary of A. Forbes Mackay 1908-1909 Dr. Allister Forbes Mackay on board the Nimrod a few days after the return from the South Magnetic Pole. The Diary of A. Forbes Mackay. 1908-1909 -1- Dr. Allister Forbes Mackay. This diary and its accompanying material are excerpted from Manuscripts in the Royal Scottish Museum Edinburgh, part 2. William S Bruce papers and diary of A Forbes Mackay. Arranged, edited and with an introduction by Joy Pitman. Information Series. Natural History 8. Edinburgh: Royal Scottish Museum, March 1982. This version is ‘By Kind Permission of National Museums Scotland.’ This edition of 100 copies was issued by The Erebus & Terror Press, Jaffrey, New Hampshire, for those attending the SouthPole-sium v.2 Craobh Haven, Scotland, 1-4 May 2015. Certain images and footnotes were not included. Printed at Savron Graphics Jaffrey, New Hampshire April 2015 INTRODUCTION by Joy Pitman LISTER FORBES MACKAY was born on February 22, 1878, in Carskey, Southend, A Argyllshire, son of Colonel Alexander Forbes Mackay and Margaret Isabella (Innes) Mackay. While his parents were in India, he was brought up in Campbeltown. The family later moved to Edinburgh, where he attended George Watson’s College. Mackay did biological work under Professor Geddes and D’Arcy Thomson at Dundee. He served as a trooper in South Africa and later with Baden Powell’s police. After returning to graduate from Edinburgh in 1901 as M.B., CH.B., he went back to the front as a civil surgeon. Later he entered the Navy as a surgeon, but retired after four years to join Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition. -

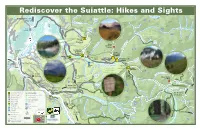

Rediscover the Suiattle: Hikes and Sights

Le Conte Chaval, Mountain Rediscover the Suiattle:Mount Hikes and Sights Su ia t t l e R o Crater To Marblemount, a d Lake Sentinel Old Guard Hwy 20 Peak Bi Buckindy, Peak g C reek Mount Misch, Lizard Mount (not Mountain official) Boulder Boat T Hurricane e Lake Peak Launch Rd na Crk s as C en r G L A C I E R T e e Ba P E A K k ch e l W I L D E R N E S S Agnes o Mountain r C Boulder r e Lake e Gunsight k k Peak e Cub Trailhead k e Dome e r Lake Peak Sinister Boundary e C Peak r Green Bridge Put-in C y e k Mountain c n u Lookout w r B o e D v Darrington i Huckleberry F R Ranger S Mountain Buck k R Green Station u Trailhead Creek a d Campground Mountain S 2 5 Trailhead Old-growth Suiattle in Rd Mounta r Saddle Bow Grove Guard een u Gr Downey Creek h Mountain Station lp u k Trailhead S e Bannock Cr e Mountain To I-5, C i r Darrington c l Seattle e U R C Gibson P H M er Sulphur S UL T N r S iv e uia ttle R Creek T e Falls R A k Campground I L R Mt Baker- Suiattle d Trailhead Sulphur Snoqualmie Box ! Mountain Sitting Mountain Bull National Forest Milk n Creek Mountain Old Sauk yo Creek an North Indigo Bridge C Trailhead To Suiattle Closure Lake Lime Miners Ridge White Road Mountain No Trail Chuck Access M Lookout Mountain M I i Plummer L l B O U L D E R Old Sauk k Mountain Rat K Image Universal C R I V E R Trap Meadow C Access Trail r Lake Suiattle Pass Mountain Crystal R e W I L D E R N E S S e E Pass N Trailhead Lake k Sa ort To Mountain E uk h S Meadow K R id Mountain T ive e White Chuck Loop Hwy ners Cre r R i ek R M d Bench A e Chuc Whit k River I I L Trailhead L A T R T Featured Trailheads Land Ownership S To Holden, E Other Trailheads National Wilderness Area R Stehekin Fire C Mountain Campgrounds National Forest I C Beaver C I F P A Fortress Boat Launch State Conservation Lake Pugh Mtn Mountain Trailhead Campground Other State Road Helmet Butte Old-growth Lakes Mt. -

Mt. Baker Ski Area

Winter Activity Guide Mount Baker Ranger District North Cascades National Park Contacts Get ready for winter adventure! Head east along the Mt. Baker Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest State Road Conditions: /Mt. Baker Ranger District Washington State Dept. of Transportation Highway to access National Forest 810 State Route 20 Dial 511 from within Washington State lands and the popular Mt. Baker Ski Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284 www.wsdot.wa.gov Area. Travel the picturesque North (360) 856-5700 ext. 515 Glacier Public Service Center Washington State Winter Recreation and Cascades Highway along the Skagit 10091 Mt. Baker Highway State Sno-Park Information: Wild & Scenic River System into the Glacier, WA 98244 www.parks.wa.gov/winter heart of the North Cascades. (360) 599-2714 http://www.fs.usda.gov/mbs Mt. Baker Ski Area Take some time for winter discovery but North Cascades National Park Service Ski Area Snow Report: be aware that terrain may be challenging Complex (360) 671-0211 to navigate at times. Mountain weather (360) 854-7200 www.mtbaker.us conditions can change dramatically and www.nps.gov/noca with little warning. Be prepared and check Cross-country ski & snowshoe trails along the Mt. Baker Highway: forecasts before heading out. National Weather Service www.weather.gov www.nooksacknordicskiclub.org Northwest Weather & Avalanche For eagle watching information visit: Travel Tips Center: Skagit River Bald Eagle Interpretive Center Mountain Weather Conditions www.skagiteagle.org • Prepare your vehicle for winter travel. www.nwac.us • Always carry tire chains and a shovel - practice putting tire chains on before you head out. -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES Fall, 1984 2 The Wild Cascades PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE ONCE THE LINES ARE DRAWN, THE BATTLE IS NOT OVER The North Cascades Conservation Council has developed a reputation for consistent, hard-hitting, responsible action to protect wildland resources in the Washington Cascades. It is perhaps best known for leading the fight to preserve and protect the North Cascades in the North Cascades National Park, the Pasayten and Glacier Peak Wilderness Areas, and the Ross Lake and Lake Chelan National Recreation Areas. Despite the recent passage of the Washington Wilderness Act, many areas which deserve and require wilderness designation remain unprotected. One of the goals of the N3C must be to assure protection for these areas. In this issue of the Wild Cascades we have analyzed the Washington Wilderness Act to see what we won and what still hangs in the balance (page ). The N3C will continue to fight to establish new wilderness areas, but there is also a new challenge. Our expertise is increasingly being sought by government agencies to assist in developing appropriate management plans and to support them against attempts to undermine such plans. The invitation to participate more fully in management activities will require considerable effort, but it represents a challenge and an opportunity that cannot be ignored. If we are to meet this challenge we will need members who are either knowledgable or willing to learn about an issue and to guide the Board in its actions. The Spring issue of the Wild Cascades carried a center section with two requests: 1) volunteers to assist and guide the organization on various issues; and 2) payment of dues. -

Northeast Chapter Volunteer Hours Report for Year 2013-2014

BACK COUNTRY HORSEMEN OF WASHINGTON - Northeast Chapter Volunteer Hours Report for Year 2013-2014 Work Hours Other Hours Travel Equines Volunteer Name Project Agency District Basic Skilled LNT Admin Travel Vehicle Quant Days Description of work/ trail/trail head names Date Code Code Hours Hours Educ. Pub. Meet Time Miles Stock Used AGENCY & DISTRICT CODES Agency Code Agency Name District Codes for Agency A Cont'd A U.S.F.S. District Code District Name B State DNR OKNF Okanogan National Forest C State Parks and Highways Pasayten Wilderness D National Parks Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness E Education and LNT WNF Wenatchee National Forest F Dept. of Fish and Wildlife (State) Alpine Lakes Wilderness G Other Henry M Jackson Wilderness M Bureau of Land Management William O Douglas Wilderness T Private or Timber OLNF Olympic National Forest W County Mt Skokomish Wilderness Wonder Mt Wilderness District Codes for U.S.F.S. Agency Code A Colonel Bob Wilderness The Brothers Wilderness District Code District Name Buckhorn Wilderness CNF Colville National Forest UMNF Umatilla National Forest Salmo-Priest Wilderness Wenaha Tucannon Wilderness GPNF Gifford Pinchot National Forest IDNF Idaho Priest National Forest Goat Rocks Wilderness ORNF Oregon Forest Mt Adams Wilderness Indian Heaven Wilderness Trapper Wilderness District Codes for DNR Agency B Tatoosh Wilderness MBS Mt Baker Snoqualmie National Forest SPS South Puget Sound Region Glacier Peak Wilderness PCR Pacific Cascade Region Bolder River Wilderness OLR Olympic Region Clear Water Wilderness NWR Northwest Region Norse Peak Mt Baker Wilderness NER Northeast Region William O Douglas Wilderness SER Southeast Region Glacier View Wilderness Boulder River Wilderness VOLUNTEER HOURS GUIDELINES Volunteer Name 1.