Expression in Technical Exercises for the Cello: an Artistic Approach to Teaching and Learning the Caprices of Piatti and Etudes of Popper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Application of the Kinesthetic Sense: an Introduction of Body Awareness in Cello Pedagogy and Performance

The Application of the Kinesthetic Sense: An Introduction of Body Awareness in Cello Pedagogy and Performance A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2014 by Gustavo Carpinteyro-Lara BM, University of Southern Mississippi, 2001 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2003 Committee Chair: Lee Fiser, BM Abstract This document on cello pedagogy and playing focuses on the importance of the kinesthetic sense as it relates to teaching and performance quality. William Conable, creator of body mapping, has described how the kinesthetic sense or movement sense provides information about the body’s position and size, and whether the body is moving and, if so, where and how. In addition Craig Williamson, pioneer of Somatic Integration, claims that the kinesthetic sense enables one to sense what the body is doing at any time, including muscular effort, tension, relaxation, balance, spatial orientation, distance, and proportion. Cellists can develop and awaken the kinesthetic sense in order to have conscious body awareness, and to understand that cello playing is a physical, aerobic, intellectual, and musical activity. This document describes the physical, motion, aerobic, anatomic, and kinesthetic approach to cello playing and is supported by somatic education methods, such as the Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais Method, and Yoga. By applying body awareness and kinesthesia in cello playing, cellists can have freedom, balance, ease in their movements, and an intelligent way of playing and performing. ii Copyright © 2014 by Gustavo Carpinteyro-Lara. -

[email protected] N

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED May 28, 2015 February 17, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC TO RETURN TO BRAVO! VAIL FOR 13th-ANNUAL SUMMER RESIDENCY, JULY 24–31, 2015 Music Director Alan Gilbert To Lead Three Programs Bramwell Tovey and Joshua Weilerstein Also To Conduct Soloists To Include Violinist Midori, Cellist Alisa Weilerstein, Pianists Jon Kimura Parker and Anne-Marie McDermott, Acting Concertmaster Sheryl Staples, Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps, Soprano Julia Bullock, and Tenor Ben Bliss New York Philharmonic Musicians To Perform Chamber Concert The New York Philharmonic will return to Bravo! Vail in Colorado for the Orchestra’s 13th- annual summer residency there, featuring six concerts July 24–31, 2015, as well as a chamber music concert performed by Philharmonic musicians. Music Director Alan Gilbert will conduct three programs, July 29–31, including an all-American program and works by Mendelssohn, Mahler, Mozart, and Shostakovich. The other Philharmonic concerts, conducted by Bramwell Tovey (July 24 and 26) and former New York Philharmonic Assistant Conductor Joshua Weilerstein (July 25), will feature works by Grieg, Elgar, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Richard Strauss, among others. The soloists appearing during the Orchestra’s residency are pianists Jon Kimura Parker and Anne-Marie McDermott, cellist Alisa Weilerstein, violinist Midori, soprano Julia Bullock and tenor Ben Bliss, and Acting Concertmaster Sheryl Staples and Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps. The New York Philharmonic has performed at Bravo! Vail each summer since 2003. Alan Gilbert will lead the concert on Wednesday, July 29, featuring Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, with Midori as soloist, and Mahler’s Symphony No. -

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Violino Gianantonio Viero, Violoncello A.Vivaldi Concerto in La Min

2010 Con il Contributo Ente Copromotore Regione Liguria Provincia della Spezia Assessorato alla Cultura Sponsor principale Enti patrocinatori Comune di Carro Si ringrazia Regione Liguria Signor Angelo Berlangieri Assessore alla Cultura Sport Spettacolo, Signor Daniele Biello Provincia della Spezia Signor Marino Fiasella Presidente, Signora Pa- ola Sisti Assessore alla Cultura, Signora Elisabetta Pieroni Comune della Spezia Signor Massimo Federici Sindaco, Comune di Carro Signor Antonio Solari Sindaco Comune di Beverino Signor Andrea Costa Sindaco, Comune di Bo- nassola Signor Andrea Poletti Sindaco, Signor Giampiero Raso Assessore alla Cultura, Comune di Rocchetta Vara Signor Riccardo Barotti Sindaco, Comune di Santo Stefano di Magra Signor Juri Mazzanti Sindaco, Comune di Sesta Godano Signor Giovanni Lucchetti Morlani Sindaco, Co- mune di Varese Ligure Signora Michela Marcone Sindaco, Signor Adriano Pietronave, Signora Maria Cristina De Paoli Istituzione per i servizi Culturali del Comune della Spezia Signora Cinzia Aloisini CAMeC Signor Giacomo Borrotti Teatro Civico Signora Patrizia Zanzucchi, Signor Luigi Lu- petti Camera di Commercio Industria Agricoltura e Arti- gianato della Spezia Signor Aldo Sammartano Presidente, Pro Loco Niccolò Paganini di Carro Signor Giuseppe Garau Presidente, Signora Teresa Paganini Associazione Amici del Festival Paganiano di Carro Sig.ra Monica Amari Staglieno Presidente Associazione Amici di Paganini Signor Enrico Volpato Presidente Questa pubblicazione è stata curata da Andrea Barizza l’omaggio Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2010 Convegno giovedì 15 luglio La Spezia ore 21.00 Teatro Civico I Solisti veneti diretti da 4 Claudio Scimone Programma Il virtuosismo strumentale da Vivaldi a Paganini Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2010 Convegno Programma A.Vivaldi Dall’Opera Terza L’Estro Armonico Concerto n.11 in Re min. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Techniques in David Popper's Hohe Schule Des Violoncello-Spiels, Op. 73

Conservatorium of Music Techniques in David Popper's Hohe Schule des Violoncello-Spiels, op. 73 by Felicity Allan-Eames Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Music (Honours) University of Tasmania (June, 2013) DECLARATION I declare that all material in this exegesis is my own work except where there is clear acknowledgement or reference to the work of others and I have read the University statement on Academic misconduct (Plagia rism) on the University website at www.utas.edu.au/plagiarism or in the Student Information Handbook. I further declare that no part of this pa per has been submitted for assessment in any other unit at this university or any other institution. I consent the authority of access to copying this exegesis. This authority is subject to any agreement entered into by the University concerning access to the exegesis. Felicity Allan-Eames 6th June 2013 ABSTRACT Virtuoso cellist, pedagogue and composer, David Popper was an instru mental figure in the development of cello technique in the late nine teenth and early twentieth centuries. Popper's technical principles and innovations are laid down in his monumental work the Hohe Schule des Violoncello-Spiels. Certainly his greatest contribution, these forty im mensely challenging and musically-rewarding etudes are now studied all over the world. A thorough understanding of the many techniques re quired in these etudes, as well as effective practice methods, are cru cial for a cellist's development of technical skills. These techniques and practice methods have been somewhat overlooked in the available liter ature. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 27,1907-1908, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL - - NEW YORK Twenty-second Season in New York DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor fnigrammra of % FIRST CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 7 AT 8.15 PRECISELY AND THK FIRST MATINEE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 9 AT 2.30 PRECISELY WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER : Piano. Used and indorsed by Reisenauer, Neitzel, Burmeister, Gabrilowitsch, Nordica, Campanari, Bispham, and many other noted artists, will be used by TERESA CARRENO during her tour of the United States this season. The Everett piano has been played recently under the baton of the following famous conductors Theodore Thomas Franz Kneisel Dr. Karl Muck Fritz Scheel Walter Damrosch Frank Damrosch Frederick Stock F. Van Der Stucken Wassily Safonoff Emil Oberhoffer Wilhelm Gericke Emil Paur Felix Weingartner REPRESENTED BY THE JOHN CHURCH COMPANY . 37 West 32d Street, New York Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1907-1908 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor First Violins. Wendling, Carl, Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Czerwonky, R. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. < Second Violins. • Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Rennert, B. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H Kuntz, A. Swornsbourne, W. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Goldstein, H. Violas. Ferir, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. t Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loefner, E. Heberlein, H. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

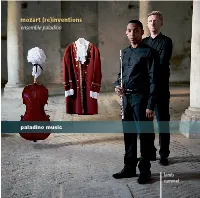

Mozart (Re)Inventions Ensemble Paladino

RZ_pmr0050_BOOKLET-Lamb-Rummel_24-stg_Layout 1 22.12.14 17:58 Seite 1 mozart (re)inventions ensemble paladino lamb rummel RZ_pmr0050_BOOKLET-Lamb-Rummel_24-stg_Layout 1 22.12.14 17:58 Seite 2 RZ_pmr0050_BOOKLET-Lamb-Rummel_24-stg_Layout 1 22.12.14 17:58 Seite 3 mozart (re)inventions eric lamb & martin rummel 3 RZ_pmr0050_BOOKLET-Lamb-Rummel_24-stg_Layout 1 22.12.14 17:58 Seite 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) arr. Eric Lamb & Martin Rummel from “Die Zauberflöte“ from the “London Sketchbook” (“The Magic Flute”), K 620 07 […] K Anh. 109b, No 1 (K 15a) 01:40 01 “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” 01:27 02 “Das klinget so herrlich” 01:21 08 Menuet in G Major, K 1 (1e) 02:13 09 Menuet in F Major, K 2 00:58 Duo in G Major, K 423 10 Allegro in B Flat Major, K 3 01:05 (original for violin and viola) 11 Andante in F Major, K 6 03:10 03 Allegro 06:58 12 Menuet in D Major, K 7 01:10 04 Adagio 03:34 13 […] K 15hh 01:58 05 Rondeau. Allegro 05:29 14 […] K 33b 01:12 06 Allegro in C Major 02:27 Duo in B Flat Major, K 424 (original for violin and viola) 15 Adagio - Allegro 08:43 16 Andante cantabile 03:06 17 Andante con variazioni 09:09 from “Die Zauberflöte“ (“The Magic Flute”), K 620 18 “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” 01:07 19 “Wie stark ist nicht dein Zauberton” 02:50 TT 59:40 4 RZ_pmr0050_BOOKLET-Lamb-Rummel_24-stg_Layout 1 22.12.14 17:58 Seite 5 Eric Lamb, flute Martin Rummel, cello 5 RZ_pmr0050_BOOKLET-Lamb-Rummel_24-stg_Layout 1 22.12.14 17:58 Seite 6 RZ_pmr0050_BOOKLET-Lamb-Rummel_24-stg_Layout 1 22.12.14 17:58 Seite 7 “Mozart (re)inventions” is ensemble paladino’s The Duos K 423 and 424 were written in Salzburg continued reimagining and exploration of classical works during the summer of 1783, as favors for his old friend of great composers. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

The St. Petersburg String Quartet Alla Aranovskaya

THE ST. PETERSBURG STRING QUARTET ALLA ARANOVSKAYA, VIOLIN BORIS VAYNER, VIOLA ALLA KROLEVICH, VIOLIN LEONID SHUKAEV, CELLO ASSISTING ARTIST: PETER KOLKAY, BASSOON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2010 AT 3PM PROGRAM STRING QUARTET IN B FLAT MAJOR, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart K. 458 "Hunt" (1784) (1756-1791) Allegro vivace assai Menuetto: Moderato Adagio Adagio assai This is the 13th performance of the Hunt Quartet at Music Mountain QUINTET FOR BASSOON & STRINGS, OPUS 14 (1997) Russell Platt (1965.....) Slow Movement Song Still Slow-Fast This is the Music Mountain premier of the Platt Bassoon Quintet INTERMISSION (Intermission Recital by Students of the St. Petersburg International Music Academy) STRING QUARTET IN C MINOR, Johannes Brahms OPUS 51 # 1 (1873) (1833-1897) Allegro Romanze: Poco Adagio Allegretto molto moderato e comodo Allegro This is the 25th performance of the C Minor Quartet at Music Mountain ********************* Please join us immediately after the concert in Music Mountain House for a Post Concert discussion with Peter Kolkay and others of the Bassoon and its place in Chamber Music. THE ARTISTS THE ST. PETERSBURG STRING QUARTET The St. Petersburg String Quartet is one of Music Mountain's favorite guests, having played here every year since 1995. The Quartet was formed at what was then the Leningrad Conservatory. They went on to win major honors both in the Soviet Union and abroad. For over 25 years, they have toured the United States, Europe (both East and West) and Asia. Their recordings have been nominated for Grammies and have won honors in Stereo Review and Gramophone as well as the WQXR/Chamber Music America prize for best CD of 2001.