Spook Show Francisco (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Kidnapped Santa Claus L

Vocabulary lists are available for these titles: A Blessing Richard Wright A Boy at War Harry Mazer A Break with Charity Ann Rinaldi A Case of Identity Sir Arthur Conan Doyle A Christmas Carol Charles Dickens A Christmas Memory Truman Capote A Clockwork Orange Anthony Burgess A Corner of the Universe Ann M. Martin A Cup of Cold Water Christine Farenhorst A Dark Brown Dog Stephen Crane A Day No Pigs Would Die Robert Newton Peck A Day's Wait Ernest Hemingway A Doll's House Henrik Ibsen A Door in the Wall Marguerite De Angeli A Farewell to Arms Ernest Hemingway A Game for Swallows Zeina Abirached A Jury of Her Peers Susan Glaspell A Just Judge Leo Tolstoy www.wordvoyage.com A Kidnapped Santa Claus L. Frank Baum A Land Remembered Patrick D. Smith A Lion to Guard Us Clyde Robert Bulla A Long Walk to Water Linda Sue Park A Mango-Shaped Space Wendy Mass A Marriage Proposal Anton Chekhov A Midsummer Night's Dream William Shakespeare A Midsummer Night's Dream for Kids Lois Burdett A Night Divided Jennifer A. Nielsen A Painted House John Grisham A Pale View of Hills Kazuo Ishiguro A Raisin in the Sun Lorraine Hansberry A Retrieved Reformation O. Henry A Rose for Emily William Faulkner A Separate Peace John Knowles A Single Shard Linda Sue Park A Sound of Thunder Ray Bradbury A Stone in My Hand Cathryn Clinton A Streetcar Named Desire Tennessee Williams A String of Beads W. Somerset Maugham A Tale Dark and Grimm Adam Gidwitz A Tale of Two Cities Charles Dickens www.wordvoyage.com A Tangle of Knots Lisa Graff A Telephone Call Dorothy Parker A Thousand Never Evers Shana Burg A Thousand Splendid Suns Khaled Hosseini A Visit of Charity Eudora Welty A Week in the Woods Andrew Clements A Wind In The Door Madeleine L'Engle A Worn Path Eudora Welty A Wrinkle In Time Madeleine L'Engle Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, The Sherman Alexie Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt Across the Lines Caroline Reeder Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie Kristiana Gregory Adam of the Road Elizabeth Gray Adoration of Jenna Fox, The Mary E. -

Biblioteca Digital De Cartomagia, Ilusionismo Y Prestidigitación

Biblioteca-Videoteca digital, cartomagia, ilusionismo, prestidigitación, juego de azar, Antonio Valero Perea. BIBLIOTECA / VIDEOTECA INDICE DE OBRAS POR TEMAS Adivinanzas-puzzles -- Magia anatómica Arte referido a los naipes -- Magia callejera -- Música -- Magia científica -- Pintura -- Matemagia Biografías de magos, tahúres y jugadores -- Magia cómica Cartomagia -- Magia con animales -- Barajas ordenadas -- Magia de lo extraño -- Cartomagia clásica -- Magia general -- Cartomagia matemática -- Magia infantil -- Cartomagia moderna -- Magia con papel -- Efectos -- Magia de escenario -- Mezclas -- Magia con fuego -- Principios matemáticos de cartomagia -- Magia levitación -- Taller cartomagia -- Magia negra -- Varios cartomagia -- Magia en idioma ruso Casino -- Magia restaurante -- Mezclas casino -- Revistas de magia -- Revistas casinos -- Técnicas escénicas Cerillas -- Teoría mágica Charla y dibujo Malabarismo Criptografía Mentalismo Globoflexia -- Cold reading Juego de azar en general -- Hipnosis -- Catálogos juego de azar -- Mind reading -- Economía del juego de azar -- Pseudohipnosis -- Historia del juego y de los naipes Origami -- Legislación sobre juego de azar Patentes relativas al juego y a la magia -- Legislación Casinos Programación -- Leyes del estado sobre juego Prestidigitación -- Informes sobre juego CNJ -- Anillas -- Informes sobre juego de azar -- Billetes -- Policial -- Bolas -- Ludopatía -- Botellas -- Sistemas de juego -- Cigarrillos -- Sociología del juego de azar -- Cubiletes -- Teoria de juegos -- Cuerdas -- Probabilidad -

Bill Konigsberg Is the Award-Winning Author of Six Young Adult Novels

WRITERS WEEK 2021 WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 10 JULIA SCHEERES After graduating from the University of Southern California with an M.A. in Journalism, Julia worked as a daily reporter for the Los Angeles Times and El Financiero de Mexico. In 2005, she published a memoir called Jesus Land, which was a New York Times and London Times bestseller. In 2011, she published a narrative history of the Jonestown tragedy called A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Jonestown. Between books, she writes features, essays, profiles and book reviews for magazines and newspapers; does content writing for companies; and works with private clients. In addition to writing, she has taught memoir and narrative writing for over a decade – to beginning writers and MFA students alike. WRITERS WEEK 2021 BILL THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 11 KONIGSBERG Bill Konigsberg is the award-winning author of six young adult novels. The Porcupine of Truth won the PEN Center USA Literary Award and the Stonewall Book Award in 2016. Openly Straight won the Sid Fleischman Award for Humor, was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in 2014 and has been translated into five languages. His debut novel, Out of the Pocket, won the Lambda Literary Award in 2009. The Music of What Happens, released in 2019, received two starred reviews, and has been optioned for a film. His latest novel, The Bridge, was released in the fall of 2020. It has received two starred reviews. In 2018, The National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE)’s Assembly on Literature for Adolescents (ALAN) established the Bill Konigsberg Award for Acts and Activism for Equity and Inclusion through Young Adult Literature. -

Great California Fiction at the Pleasanton Public Library

Earthquake at Dawn by Kristiana Gregory must deal with his feelings about the war, Japanese internment camps, California Historical Fiction his father, and his own identity. Grades 5-8 (192 p) A novelization of twenty-two-year-old photographer, Edith Irvine’s Carlota by Scott O’Dell by Gennifer Choldenko experience in the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, as Al Capone Does My Shirts Grades 5-8 (153 p) Great Grades 5-8 (228 p) Audiobook available seen through the eyes of fifteen-year-old Daisy, a fictitious traveling A young California girl learns to deal with her father’s Sequel: Al Capone Shines My Shoes companion. expectations that she act as the son he lost years before. A twelve-year-old boy named Moose moves to Alcatraz California She relates her feelings and experiences as a participant Island in 1935 when guards’ families were housed there, Seeds of Hope: The Goldrush Diary of Suzanna in the Battle of San Pasqual during the last days of the and has to contend with his extraordinary new Fairchild war between the Californians and Americans. Fiction environment in addition to life with his autistic sister. by Kristiana Gregory Grades 5-8 (186 p) Dear America series The Ballad of Lucy Whipple by Karen Cushman A diary account of fourteen-year-old Susanna Fairchild’s life in 1849. Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O’Dell at the Grades 4-8 (195 p) Audiobook available Her father succumbs to gold fever and abandons his plan of Grades 4-7 (189 p) Audiobook available Twelve-year-old California Morning Whipple moves with her establishing a medical practice in Oregon after losing his wife and This book records the courage and self-reliance of an Pleasanton widowed mother and younger siblings to a California gold-mining money on their steamboat journey from New York. -

Great Reads for 4Th & 5Th Grade! Contemporary Realistic Fiction Out

Great Reads for 4th & 5th grade! Contemporary Realistic Fiction Because of Winn Dixie- Kate DiCamillo (F Dic) Ten year old India Opal Buloni describes her first summer in the town of Naomi, Florida, and all the good things that happen to her because of her big ugly dog Winn- Dixie. Frindle-Andrew Clements (F Cle) When he decides to turn his fifth-grade teacher's love of the dictionary around on her, clever Nick Allen invents a new word and begins a chain of events that quickly moves beyond his control. Flush-Carl Hiaasen (F Hia) With their father jailed for sinking a river boat, Noah Underwood and his younger sister, Abbey, must gather evidence that the owner of this floating casino is emptying his bilge tanks into the protected waters around their Florida Keys home. Homework Machine-Dan Gutman (F Gut) Four fifth-grade students--a geek, a class clown, a teacher's pet, and a slacker--as well as their teacher and mothers, each relate events surrounding a computer programmed to complete homework assignments. Hoot-Carl Hiaasen (F Hia) Roy, who is new to his small Florida community, becomes involved in another boy's attempt to save a colony of burrowing owls from a proposed construction site. Lawn Boy-Gary Paulsen (F Pau) Things get out of hand for a twelve-year-old boy when a neighbor convinces him to expand his summer lawn mowing business. Mother Daughter Book Club-Heather Vogel Fredrick No Talking -Andrew Clements (F Cle) The noisy fifth grade boys of Laketon Elementary School challenge the equally loud fifth grade girls to a "no talking" contest. -

Saints Catholic School Recommended Books by Lexile Level

All Saints Catholic School Recommended Books by Lexile Level You will receive your child’s lexile reading level with the first progress report. Educational research has proven that students who read at or slightly above their reading level will make the most progress in reading. To assist you and your child in finding books to read on his/her appropriate level, we have compiled the following recommended titles. There is also a website that you can use to search titles; however this website is based on readability only, not on content appropriateness. If you use this site, be sure to read the book summary before approving for your child. The website url is https://www.lexile.com/findabook/. Lexile Level 0 - 100 Autumn Leaves by Gail Saunders-Smith The Berenstain Bears in the House of Mirrors by Stan & Jan Berenstain Cars by Gail Saunders-Smith Count and See by Tana Hoban Do You Want to Be My Friend? by Eric Carle Growing Colors by Bruce McMillan Look what I Can Do by Jose Aruego My Book by Ron Maris My Class by Lynn Salem What Do Insects Do? by Susan Canizares Cat on the Mat by Brian Wildsmith Chickens by Peter Brady Fun with Hats by Lucy Malka Hats around the World by Liza Charlesworth Have You Seen My Cat? by Eric Carle Have You Seen My Duckling? by Nancy Tafuri The Headache by Rod Hunt Mrs. Wishy-washy by Joy Cowley Where’s the Fish? by Taro Gomi All Fall Down by Brian Wildsmith Baby Says by John Steptoe Boats by Gail Saunders-Smith Brown Bear, Brown Bear by Bill Martin Cars by Gail Saunders-Smith Costumes by Lola Schaefer Eating Apples -

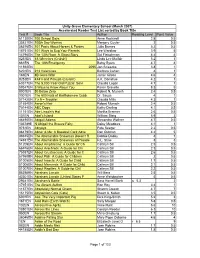

Test # Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value 61130EN 100

Unity Grove Elementary School (March 2007) Accelerated Reader Test List sorted by Book Title Test # Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value 61130EN 100 School Days Anne Rockwell 2.8 0.5 35821EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 3 0.5 56576EN 101 Facts About Horses & Ponies Julia Barnes 5.2 0.5 18751EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5 14796EN The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman 4.4 4 8251EN 18-Wheelers (Cruisin') Linda Lee Maifair 5.2 1 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 3.8 1 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 4 1 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups (Cruisin') A.K. Donahue 4.2 1 60317EN The 5,000-Year-Old Puzzle: Solvi Claudia Logan 4.7 1 59347EN 5 Ways to Know About You Karen Gravelle 8.3 5 8001EN 50 Below Zero Robert N. Munsch 2.4 0.5 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 4 1 57142EN 7 x 9 = Trouble! Claudia Mills 4.3 1 51654EN Aaron's Hair Robert Munsch 2.4 0.5 70144EN ABC Dogs Kathy Darling 4.1 0.5 11151EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner 2.6 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 46490EN Abigail Adams Alexandra Wallner 4.7 0.5 105789E N Abigail the Breeze Fairy Daisy Meadows 4.1 1 9751EN Abiyoyo Pete Seeger 2.2 0.5 86479EN Abner & Me: A Baseball Card Adve Dan Gutman 4.2 5 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't R Debbie Dadey 4 1 14931EN The Abominable Snowman of Pasade R.L. -

ONE-LETTER WORDS a Dictionary for M

www.IELTS4U.blogfa.com www.IELTS4U.blogfa.com CRAIG CONLEY ONE-LETTER WORDS A Dictionary www.IELTS4U.blogfa.com For M. T. Wentz The conquest of the superfluous gives us greater spiritual excitement than the conquest of the necessary. — Gaston Bachelard, French philosopher www.IELTS4U.blogfa.com www.IELTS4U.blogfa.com www.IELTS4U.blogfa.comINTRODUCTION WHEN THE WORDS GET IN THE WAY Ninety- nine down: a one letter word meaning something indefi nite. The indefinite article or—would it perhaps be the personal pronoun? But what runs across it? Four letter word meaning something With a bias towards its opposite, the second letter Must be the same as the one letter word. It is time We left these puzzles and started to be ourselves. And started to live, is it not? —Louis MacNeice, Solstices e live in a world of mass communication. As you read this, words are staring you W in the face. But they’re not the only ones. Miles above you, words are flown in jets across the country and over the oceans. They are www.IELTS4U.blogfa.comtossed at 5 a.m. on newspaper routes. They are deliv- ered six days a week by mail carriers. They’re propped up on display at book stores. They’re bouncing off satellites and showing up on television and cell phone screens. We are constantly bombarded by language pollution. And these empty words are overwhelming. Either they scream out to be noticed (as in TV commercials), or they hide in small print (at the bottom of contracts), or they bury their meaning behind jargon (generated by computers and bureaucracy). -

Downloading the Digital Edition of Our Summer 2013 Shelf Sale Catalog

Public Auction #020 Shelf Sale Including Contemporary & Collectible Conjuring Books; Epemera & Posters; Modern & Vintage Magic Apparatus; and More Auction Saturday, July 27th 2013 - 10:00 Am Exhibition July 24 - 26, 10:00 am - 5:00 pm Inquries [email protected] Phone: 773-472-1442 Potter & Potter Auctions, Inc. 3759 N. Ravenswood Ave. -Suite 121- Chicago, IL 60613 Thank you for downloading the digital edition of our Summer 2013 Shelf Sale Catalog. Additional detailed photos — of every lot in the auction, including those not pictured here — can be viewed on our partner website, www. liveauctioneers.com. 3 1 2 4 AppArAtus And MAgic sets 1. Block Through Board. Florida, Paul Lembo, ca. 2005. 3. Delben Blotter. Ben Stone, ca. 1980. A wooden blotter that Modeled after the effect made famous by Karl Germain. A solid visibly transforms a blank slip of paper into a real dollar bill. block penetrates a solid black board in several locations, and at Hallmarked. With instructions and resetting device. Good different angles. Includes two blocks, board, tray, and gimmicks. condition. Board 12 ¼ x 9 ½”, blocks 12” long. With instructions. Modeled 100/150 after the popular UF Grant model. Very good. 300/500 4. Booth, John. Booth’s Magicraft Set. Hamilton Ontario, Homecrafters Guild, ca. 1930. Magic set created and crafted by 2. Blooming Bouquet. Akron Ohio, Horace Marshall, ca. 1945. John Booth early in his career. Props and instructions packaged Flowers are plucked from a bouquet and dropped to the floor. in a 5 x 8” manila envelope imprinted with advertising copy Then, the flowers slowly and amazingly re-grow in the bouquet, and a picture of a young John Booth. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl -

![[Wwz5l.Ebook] the Dream Stealer Pdf Free](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0169/wwz5l-ebook-the-dream-stealer-pdf-free-4840169.webp)

[Wwz5l.Ebook] the Dream Stealer Pdf Free

WwZ5l [FREE] The Dream Stealer Online [WwZ5l.ebook] The Dream Stealer Pdf Free Sid Fleischman audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #739003 in Books Greenwillow Books 2011-09-20 2011-09-20Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 7.63 x .26 x 5.13l, .20 #File Name: 0061787299128 pages | File size: 19.Mb Sid Fleischman : The Dream Stealer before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Dream Stealer: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Fun and entertaining readBy Michon ZuritaMy son and I love this book; have read it multiple times at our public library, so just broke down and bought a copy for ourselves! It helps that I read it in accents and with many giggles from my son. Just a precious little story that is kind of unexpected and with charming characters. Not crazy about the illustrations--this is not how I picture the Dream Stealer in my own head--but you can't fault the author for that! I recommend it for a good read-aloud and even for a read-alone for beginning readers.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. It was a great book my 10yr old son loves itBy mitchyIt was a great book my 10yr old son loves it. My son did a book report on it on the science project display board. He really did and outstanding job . I also read the book it was a great book.0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. -

A Teacher's Guide for Sid Fleischman

A Teacher’s Guide for Sid Fleischman Featuring The Whipping Boy, Jim Ugly, and Disappearing Act Grades 3 up ABOUT THE BOOKS The Whipping Boy Tr 0-688-06216-4 • Pb 0-06-052122-8 A Greenwillow Book In the Middle Ages, it was considered treasonous for anyone to spank a prince, so the orphan Jemmy is plucked off the street and forced to be the whipping boy for the disobedient and obnoxious Prince Brat. Whenever the Prince does anything that deserves a whipping, Jemmy is brought to the king and whipped severely by the guards. Jemmy plans an escape, but the Prince beats him to it, and together they leave the palace grounds to find adventure. Along the way, they meet two dangerous crooks who hold them for ransom, a young girl with a dancing bear who saves them from a beating, a man selling hot potatoes who helps them escape, and Jemmy’s old friends who live in the sewers of London catching rats. Newbery Medal ALA Notable Children’s Book School Library Journal Best Book Jim Ugly Tr 0-688-10886-5 • Pb 0-06-052121-X A Greenwillow Book Part wolf and part dog, Jim Ugly has the ability to sniff out anything and anybody. So when Jake’s father, Sam Bannock, is buried without anyone seeing the body, Jake and his dog Jim Ugly set out to prove he is still alive. Their Old West adventure leads them on a chase for missing diamonds, and they tangle with some strange stage actors who knew things about Jake’s father that Jake didn’t know, and a bounty hunter who wants Sam Bannock dead for real.