The 100 Most Influential Inventors of All Time / Edited by Robert Curley.—1St Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Years of the Acoustic Phonograph Its Developmental Origins and Fall from Favor 1877-1929

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE ACOUSTIC PHONOGRAPH ITS DEVELOPMENTAL ORIGINS AND FALL FROM FAVOR 1877-1929 by CARL R. MC QUEARY A SENIOR THESIS IN HISTORICAL AMERICAN TECHNOLOGIES Submitted to the General Studies Committee of the College of Arts and Sciences of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of BACHELOR OF GENERAL STUDIES Approved Accepted Director of General Studies March, 1990 0^ Ac T 3> ^"^^ DEDICATION No. 2) This thesis would not have been possible without the love and support of my wife Laura, who has continued to love me even when I had phonograph parts scattered through out the house. Thanks also to my loving parents, who have always been there for me. The Early Years of the Acoustic Phonograph Its developmental origins and fall from favor 1877-1929 "Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snov^. And everywhere that Mary went, the lamb was sure to go." With the recitation of a child's nursery rhyme, thirty-year- old Thomas Alva Edison ushered in a bright new age--the age of recorded sound. Edison's successful reproduction and recording of the human voice was the end result of countless hours of work on his part and represented the culmination of mankind's attempts, over thousands of years, to capture and reproduce the sounds and rhythms of his own vocal utterances as well as those of his environment. Although the industry that Edison spawned continues to this day, the phonograph is much changed, and little resembles the simple acoustical marvel that Edison created. -

Thomas Edison Vs Nikola Tesla THOMAS EDISON VS NIKOLA TESLA

M C SCIENTIFIC RIVALRIES PHERSON AND SCANDALS In the early 1880s, only a few wealthy people had electric lighting in their homes. Everyone else had to use more dangerous lighting, such as gas lamps. Eager companies wanted to be the first to supply electricity to more Americans. The early providers would set the standards—and reap great profits. Inventor THOMAS EDISON already had a leading role in the industry: he had in- vented the fi rst reliable electrical lightbulb. By 1882 his Edison Electric Light Company was distributing electricity using a system called direct current, or DC. But an inventor named NIKOLA TESLA challenged Edison. Tesla believed that an alternating cur- CURRENTS THE OF rent—or AC—system would be better. With an AC system, one power station could deliver electricity across many miles, compared to only about one mile for DC. Each inventor had his backers. Business tycoon George Westinghouse put his money behind Tesla and built AC power stations. Meanwhile, Edison and his DC backers said that AC could easily electrocute people. Edison believed this risk would sway public opinion toward DC power. The battle over which system would become standard became known as the War of the Currents. This book tells the story of that war and the ways in which both kinds of electric power changed the world. READ ABOUT ALL OF THE OF THE SCIENTIFIC RIVALRIES AND SCANDALS BATTLE OF THE DINOSAUR BONES: Othniel Charles Marsh vs Edward Drinker Cope DECODING OUR DNA: Craig Venter vs the Human Genome Project CURRENTS THE RACE TO DISCOVER THE -

Army Radio Communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE

Army radio communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE Introduction Prior to the outbreak of WW1 in August 1914 many of the techniques to be used in later years for radio communications had already been invented, although most were still at an early stage of practical application. Radio transmitters at that time were predominantly using spark discharge from a high voltage induction coil, which created a series of damped oscillations in an associated tuned circuit at the rate of the spark discharge. The transmitted signal was noisy and rich in harmonics and spread widely over the radio spectrum. The ideal transmission was a continuous wave (CW) and there were three methods for producing this: 1. From an HF alternator, the practical design of which was made by the US General Electric engineer Ernst Alexanderson, initially based on a specification by Reginald Fessenden. These alternators were primarily intended for high-power, long-wave transmission and not suitable for use on the battlefield. 2. Arc generator, the practical form of which was invented by Valdemar Poulsen in 1902. Again the transmitters were high power and not suitable for battlefield use. 3. Valve oscillator, which was invented by the German engineer, Alexander Meissner, and patented in April 1913. Several important circuits using valves had been produced by 1914. These include: (a) the heterodyne, an oscillator circuit used to mix with an incoming continuous wave signal and beat it down to an audible note; (b) the detector, to extract the audio signal from the high frequency carrier; (c) the amplifier, both for the incoming high frequency signal and the detected audio or the beat signal from the heterodyne receiver; (d) regenerative feedback from the output of the detector or RF amplifier to its input, which had the effect of sharpening the tuning and increasing the amplification. -

The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18Th Century Great Britain

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain Scott H. Zurawel Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Zurawel, Scott H., "The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain" (2011). Honors Theses. 1092. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1092 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i THE LUNAR SOCIETY OF BIRMINGHAM AND THE PRACTICE OF SCIENCE IN 18TH CENTURY GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF JOSPEH PRIESTLEY, JAMES WATT AND WILLIAM WITHERING By Scott Henry Zurawel ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2011 ii ABSTRACT Zurawel, Scott The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in Eighteenth-Century Great Britain: A Study of Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and William Withering This thesis examines the scientific and technological advancements facilitated by members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham in eighteenth-century Britain. The study relies on a number of primary sources, which range from the regular correspondence of its members to their various published scientific works. The secondary sources used for this project range from comprehensive books about the society as a whole to sources concentrating on particular members. -

The Power of Light

David N Payne Dedicated to: Guglielmo Marconi and Charles Kao Director ORC University of Southampton 1909 2009 Nobel Laureates in Physics Wireless and optical fibres The power of light GPS systems, synchronous data networks, cell phone telephony, time stamping financial trades Large scale interferometers for telescopes Optical gyroscopes Data centres/computer interconnects Financial traders You can’t beat vacuum for loss, speed of light or stability! The Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI) on Paranal Mountain Data Centre Interconnection Information flow/unit area and latency is key in supercomputers and data centres 20,000 km of fibre per data centre in Facebook alone! Vacuum transit time is 30% lower High-performance: applications in inertial guidance, navigation, platform stabilization, GPS flywheeling, etc. Lower-performance: Consumer / industrial applications in Performancemotion control, industrial limited processing, byconsumer glass electronics, core etc. Periodic lattice of holes Hollow air core Advantage: Typically less than 0.1% optical power in cladding. Ultra-low nonlinearity, lower loss? Vacuum fibre technology Fibres that largely ignore the materials from which they are made Power in glass < 0.01% low nonlinearity Transmission loss < 0.01 dB/m As you wouldLow Latencyexpect (30% from lower) vacuum! Phase insensitive Radiation hard IR transmitting The new anti-resonant fibre 22.3 µm 40.2 µm Width = 359.6 nm 20μm OFC 2016, Los Angeles, PDPTh5A.3 Low Latency data communications • Data transmission at 99.7% the speed of light in vacuum • ‘Only’ 69.4% in a conventional fibre Latency savings (vs conventional fibres): 1m 1.54 ns 100m 154 ns 1km 1.54 µs 100km 154 µs Phase Insensitive Fibres The phase of a signal in a fibre changes with temperature owing to: • Change in refractive index • Change in fibre length • Vacuum fibre temperature sensitivity 2 ps/km/K • 18.5 times smaller than conventional fibres Dr Radan Slavik Slavik et al., Scientific Reports 2015. -

Subwavelength Resolution Fourier Ptychography with Hemispherical Digital Condensers

Subwavelength resolution Fourier ptychography with hemispherical digital condensers AN PAN,1,2 YAN ZHANG,1,2 KAI WEN,1,3 MAOSEN LI,4 MEILING ZHOU,1,2 JUNWEI MIN,1 MING LEI,1 AND BAOLI YAO1,* 1State Key Laboratory of Transient Optics and Photonics, Xi’an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710119, China 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3College of Physics and Information Technology, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an 710071, China 4Xidian University, Xi’an 710071, China *[email protected] Abstract: Fourier ptychography (FP) is a promising computational imaging technique that overcomes the physical space-bandwidth product (SBP) limit of a conventional microscope by applying angular diversity illuminations. However, to date, the effective imaging numerical aperture (NA) achievable with a commercial LED board is still limited to the range of 0.3−0.7 with a 4×/0.1NA objective due to the constraint of planar geometry with weak illumination brightness and attenuated signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Thus the highest achievable half-pitch resolution is usually constrained between 500−1000 nm, which cannot fulfill some needs of high-resolution biomedical imaging applications. Although it is possible to improve the resolution by using a higher magnification objective with larger NA instead of enlarging the illumination NA, the SBP is suppressed to some extent, making the FP technique less appealing, since the reduction of field-of-view (FOV) is much larger than the improvement of resolution in this FP platform. Herein, in this paper, we initially present a subwavelength resolution Fourier ptychography (SRFP) platform with a hemispherical digital condenser to provide high-angle programmable plane-wave illuminations of 0.95NA, attaining a 4×/0.1NA objective with the final effective imaging performance of 1.05NA at a half-pitch resolution of 244 nm with a wavelength of 465 nm across a wide FOV of 14.60 mm2, corresponding to an SBP of 245 megapixels. -

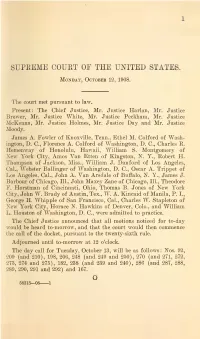

1908 Journal

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 12, 1908. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day and Mr. Justice Moody. James A. Fowler of Knoxville, Tenn., Ethel M. Colford of Wash- ington, D. C., Florence A. Colford of Washington, D. C, Charles R. Hemenway of Honolulu, Hawaii, William S. Montgomery of Xew York City, Amos Van Etten of Kingston, N. Y., Robert H. Thompson of Jackson, Miss., William J. Danford of Los Angeles, Cal., Webster Ballinger of Washington, D. C., Oscar A. Trippet of Los Angeles, Cal., John A. Van Arsdale of Buffalo, N. Y., James J. Barbour of Chicago, 111., John Maxey Zane of Chicago, 111., Theodore F. Horstman of Cincinnati, Ohio, Thomas B. Jones of New York City, John W. Brady of Austin, Tex., W. A. Kincaid of Manila, P. I., George H. Whipple of San Francisco, Cal., Charles W. Stapleton of Mew York City, Horace N. Hawkins of Denver, Colo., and William L. Houston of Washington, D. C, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would then commence the call of the docket, pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 13, will be as follows: Nos. 92, 209 (and 210), 198, 206, 248 (and 249 and 250), 270 (and 271, 272, 273, 274 and 275), 182, 238 (and 239 and 240), 286 (and 287, 288, 289, 290, 291 and 292) and 167. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

Introduction to Light Microscopy

Introduction to light microscopy A CAMDU training course Claire Mitchell, Imaging specialist, L1.01, 08-10-2018 Contents 1.Introduction to light microscopy 2.Different types of microscope 3.Fluorescence techniques 4.Acquiring quantitative microscopy data 1. Introduction to light microscopy 1.1 Light and its properties 1.2 A simple microscope 1.3 The resolution limit 1.1 Light and its properties 1.1.1 What is light? An electromagnetic wave A massless particle AND γ commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EM-Wave.gif www.particlezoo.net 1.1.2 Properties of waves Light waves are transverse waves – they oscillate orthogonally to the direction of propagation Important properties of light: wavelength, frequency, speed, amplitude, phase, polarisation upload.wikimedia.org 1.1.3 The electromagnetic spectrum 퐸푝ℎ표푡표푛 = ℎν 푐 = λν 퐸푝ℎ표푡표푛 = photon energy ℎ = Planck’s constant ν = frequency 푐 = speed of light λ = wavelength pion.cz/en/article/electromagnetic-spectrum 1.1.4 Refraction Light bends when it encounters a change in refractive index e.g. air to glass www.thetastesf.com files.askiitians.com hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Sound/imgsou/refr.gif 1.1.5 Diffraction Light waves spread out when they encounter an aperture. electron6.phys.utk.edu/light/1/Diffraction.htm The smaller the aperture, the larger the spread of light. 1.1.6 Interference When waves overlap, they add together in a process called interference. peak + peak = 2 x peak constructive trough + trough = 2 x trough peak + trough = 0 destructive www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/demos/superposition/superposition.html 1.2 A simple microscope 1.2.1 Using lenses for refraction 1 1 1 푣 = + 푚 = physicsclassroom.com 푓 푢 푣 푢 cdn.education.com/files/ Light bends as it encounters each air/glass interface of a lens. -

The Marriage That Almost Was Western Union Has Always Been R.Idiculed for Rejecting the All Telephone

RETROSPECTIVE .Innovation The marriage that almost was Western Union has always been r.idiculed for rejecting the telephone. But what actually happened wasn't so ridiculous after all The hirth of the telephone.,-one hundred years ago railway and illuminating gas to Cambridge, Mass. this month-is a fascinating story of the geJ;Jius and Long intrigued by telegraphy, he decided to do persistence of on.e man. In addition, it is an instruc something about what he called "this monopoly tive demonstration of how an industrial giant, in with its inflated capital which serves its stockhold this case the Western Union Telegraph Co., can ers better than the 'public and whose:rates are ex miss its chance to foster an industry-creating orbitant and prohibiting of many kinds of busi breakthrough-something that has happened again ness." Between 1868 and 1874, he lobbied unceas and again in electronics and other fields. ingly, shuttling back and forth betweep. homes in Between ·1875 and 1879, Western Union's chiefs Boston and Washington. for a private "postal tele engaged in an intricate minuet with Alexander graph company" to be chartered by Congress but Graham Bell and his associates. On more than one with Hubbard and some of his friends among the occasion, the telegraph colossus came excruciating incorporators. As Hubbard envisioned it, the com ly close to absorbing the small group of ~ntre pany would build telegraph lines along the nation's preneurs, That the absorption was finally avoided rail and post roads and contract with the Post was probably the result of a technological gamble Office Department to send telegrams on its wires ~t that simply didn't payoff, as rates roughly half those being charged by Western ••• The place: the ollie of well as a clash of personali Union. -

Clarence Birdseye's Outrageous Idea About Frozen Food Online

PJaze [Download ebook] Frozen in Time: Clarence Birdseye's Outrageous Idea About Frozen Food Online [PJaze.ebook] Frozen in Time: Clarence Birdseye's Outrageous Idea About Frozen Food Pdf Free Mark Kurlansky audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #237930 in Books 2014-11-11 2014-11-11Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.25 x .50 x 5.50l, .81 #File Name: 0385372442176 pages | File size: 30.Mb Mark Kurlansky : Frozen in Time: Clarence Birdseye's Outrageous Idea About Frozen Food before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Frozen in Time: Clarence Birdseye's Outrageous Idea About Frozen Food: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Makes you appreciate the genius of frozen vegetablesBy Forest ReaderWhile this is a youth book and I'm anything but, I still enjoyed it. I had never thought about how those boxes of frozen vegetables we bought when I was young had come about. (You can still buy them, but bags are more common now.) Nor had I any idea how innovative they were. Very interesting.1 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Three StarsBy angelA lot of information... but too much info on other things in his life ...rather than his personal journey0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. A parent's review: Large font, easy readingBy M. HeissThis book is geared to the level where my sixth grader can easily manage it independently. That's good, since it's a biography and a good retelling of the spirit of American entrepreneurship. -

LEARNING in the 21ST CENTURY Author Photograph : © Monsitj/Istockphoto

FRANÇOIS TADDEI LEARNING IN THE 21ST CENTURY Author photograph : © Monsitj/iStockphoto © Version française, Calmann-Lévy, 2018 SUMMARY FRANÇOIS TADDEI with Emmanuel Davidenkoff LEARNING IN THE 21ST CENTURY Translated from French by Timothy Stone SUMMARY SUMMARY To all those who have taught me so much. SUMMARY SUMMARY If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea...” Antoine de SAINT-EXUPÉRY, Citadelle SUMMARY Summary Prologue ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................13 1. Why will we learn differently st in the 21 century? ................................................................................................21 2. What i’ve learned ...........................................................................................55 3. New ways of teaching .........................................................................79 4. Before you can learn, you have to unlearn ...................................................................................113 5. Learn to ask (yourself) good questions ........................................................................................................201 6. A how-to guide for a learning planet