Carla A. Fellers “What a Wonderful World”: the Rhetoric of the Official

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Memoriam 2018: Military Figures We Lost

In Memoriam 2018: Military Figures We Lost Farewell: Remembering Those Who Died in 2018 19.6K At the close of 2018, it's time to remember some of the notable service members we lost through the year. Military Times remembers some of those who served and made their mark on the military and their country. In Memoriam 2018: Military figures we lost JANUARY Thomas Ellis, left, joins his fellow Tuskegee Airmen as they answer questions from the audience during an event at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph Air Force Base, Texas, Feb. 8, 2010. Former Sgt. Maj. Thomas Ellis, 97: He was one of six Tuskegee Airmen living in the San Antonio area when he died. He was drafted in 1942 and later spoke with pride in his unit — the first all-black Army Air Forces unit. “They had the cream of the crop in our outfit because we had to do everything better than the other outfits,” he said during a 2010 event honoring the Tuskegee Airmen. “No one will ever beat our record.” Jan. 2. In this April 1972 photo made available by NASA, John Young salutes the U.S. flag at the Descartes landing site on the moon during the first Apollo 16 extravehicular activity. NASA says the astronaut, who walked on the moon and later commanded the first space shuttle flight, died on Friday, Jan. 5, 2018. He was 87. John Young, 87: After an early career as a Navy officer who flew the F-4 Phantom II, Young became one of NASA’s pioneers and one of a select few to walk on the moon. -

Coping Strategies: Three Decades of Vietnam War in Hollywood

Coping Strategies: Three Decades of Vietnam War in Hollywood EUSEBIO V. LLÁCER ESTHER ENJUTO The Vietnam War represents a crucial moment in U.S. contemporary history and has given rise to the conflict which has so intensively motivated the American film industry. Although some Vietnam movies were produced during the conflict, this article will concentrate on the ones filmed once the war was over. It has been since the end of the war that the subject has become one of Hollywood's best-sellers. Apocalypse Now, The Return, The Deer Hunter, Rambo or Platoon are some of the titles that have created so much controversy as well as related essays. This renaissance has risen along with both the electoral success of the conservative party, in the late seventies, and a change of attitude in American society toward the recently ended conflict. Is this a mere coincidence? How did society react to the war? Do Hollywood movies affect public opinion or vice versa? These are some of the questions that have inspired this article, which will concentrate on the analysis of popular films, devoting a very brief space to marginal cinema. However, a general overview of the conflict it self and its repercussions, not only in the soldiers but in the civilians back in the United States, must be given in order to comprehend the between and the beyond the lines of the films about Vietnam. Indochina was a French colony in the Far East until its independence in 1954, when the dictator Ngo Dinh Diem took over the government of the country with the support of the United States. -

DD 214 Sept-Oct 2018

The Newspaper for Veterans and All Who Love Them. SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 YOU CAN RUN, BUT YOU CANNOT HIDE. — U.S. Navy SEALs We Honor Those Who Have Served America: OUR VETERANS GT BROTHERS AUTOMOTIVE WERNER G. SMITH, INC. 15501 Madison Avenue Bio-sustainable • (216) 226-8100 Bio-renewable • Biodegradable Lakewood, Ohio 44107 Seed Oils, Fish Oils, Esters, and Waxes MaDISON AVENUE CAR WASH 1730 Train Avenue AND DEtaIL CENTER Cleveland OH 44113-4289 11832 Madison Avenue (216) 861.3676 (216) 221-1255 wernergsmithinc.com Lakewood, Ohio 44107 [email protected] madisonavecarwash.com ELMWOOD HOME BAKERY THE MOHIcaNS 15204 Madison Avenue Treehouses • Lakewood, Ohio 44107 Wedding Venue • Cabins (216) 221-4338 23164 Vess Road Glenmont, Ohio 44628 WEST END TAVERN Office: (704) 599-9030 18514 Detroit Avenue Cell: (440) 821-6740 Lakewood, Ohio 44107 [email protected] Menus and Specials: TheMohicans.net westendtav.com Hi-def TVs for all sporting events ANDY’S SHOE & LUggagE SERVICE Celebrating 60 Years of Service Join the Companies 27227 Wolf Road Grateful for our Veterans. Bay Village, 44140 Call (216) 789-3502 or [email protected] (440) 871-1082 www.dd214chronicle.com DD 214 Chronicle September/October 2018 ✩3 STand AT EasE By John H. Tidyman, Editor VOLUME 8 NUMBER 6 WALTER PALMER, DDS; MURDERER The Newspaper for Veterans and DESERVES DEATH BY LIONS All Who Love Them. PUBLISHER EMERITUS his isn’t a new story, yet conservationists argue that fees Terence J. Uhl every time I see or read it, from hunts support conservation PUBLISHER AND EDITOR I’m sickened by dentist Wal- efforts for the big cats, whose main T John H. -

Reel-To-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Reel-to-Real: Intimate Audio Epistolarity During the Vietnam War Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alan Campbell, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Ryan T. Skinner, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Barry Shank 1 Copyrighted by Matthew Alan Campbell 2019 2 Abstract For members of the United States Armed Forces, communicating with one’s loved ones has taken many forms, employing every available medium from the telegraph to Twitter. My project examines one particular mode of exchange—“audio letters”—during one of the US military’s most trying and traumatic periods, the Vietnam War. By making possible the transmission of the embodied voice, experiential soundscapes, and personalized popular culture to zones generally restricted to purely written or typed correspondence, these recordings enabled forms of romantic, platonic, and familial intimacy beyond that of the written word. More specifically, I will examine the impact of war and its sustained separations on the creative and improvisational use of prosthetic culture, technologies that allow human beings to extend and manipulate aspects of their person beyond their own bodies. Reel-to-reel was part of a constellation of amateur recording technologies, including Super 8mm film, Polaroid photography, and the Kodak slide carousel, which, for the first time, allowed average Americans the ability to capture, reify, and share their life experiences in multiple modalities, resulting in the construction of a set of media-inflected subjectivities (at home) and intimate intersubjectivities developed across spatiotemporal divides. -

Good Morning Vietnam Full Movie Free Download Good Morning, Vietnam

good morning vietnam full movie free download Good Morning, Vietnam. Radio funny man Adrian Cronauer is sent to Vietnam to bring a little comedy back into the lives of the soldiers. After setting up shop, Cronauer delights the G.I.s but shocks his superior officer, Sergeant Major Dickerson, with his irreverent take on the war. While Dickerson attempts to censor Cronauer's broadcasts, Cronauer pursues a relationship with a Vietnamese girl named Trinh, who shows him the horrors of war first-hand. Good Morning, Vietnam - watch online: stream, buy or rent. Currently you are able to watch "Good Morning, Vietnam" streaming on Disney Plus. It is also possible to buy "Good Morning, Vietnam" on Apple iTunes, Google Play Movies, Amazon Video, Microsoft Store, YouTube as download or rent it on Apple iTunes, Google Play Movies, Amazon Video, YouTube online. Good Morning, Vietnam. Add HBO Max™ to any Hulu plan for an additional $14.99/month . New subscribers only. Good Morning, Vietnam. Robin Williams portrays Armed Forces Radio deejay Adrian Cronauer whose manic morning show incites laughs and controversy in Vietnam. Start Your Free Trial. About this Movie. Good Morning, Vietnam. Robin Williams portrays Armed Forces Radio deejay Adrian Cronauer whose manic morning show incites laughs and controversy in Vietnam. Starring: Robin Williams Forest Whitaker Tung Thanh Tran Chintara Sukapatana B. Kirby Jr. Good Morning, Vietnam. Good morning, vietnam is a 1987 american war-comedy film written by mitch markowitz and directed by barry levinson. set in saigon in 1965, during the vietnam war, the film stars robin williams as a radio dj on armed forces radio service, who proves hugely popular with the troops, but infuriates his superiors with what they call his "irreverent tendency". -

Attorney News - October 2014

Click here to view this email in your browser Attorney News - October 2014 Articles & Updates Things to Remember • Guidance on Social, Political • Follow the Disciplinary Board on Activities of Judges and Candidates Twitter Issued • Former Top Legislative Aide Disbarred for Bonusgate Conviction • Comments on Fiduciary Funds Rule Proposal Due November 3 • Pennsylvania Courts Webpage Helps Self-Representing Litigants • Not Such a Good Morning, Vietnam • Anything that Can Go Wrong . This newsletter is intended to inform and educate members of the legal profession regarding activities and initiatives of the Disciplinary Board of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. To ensure you receive each newsletter and announcement from the Disciplinary Board of the Supreme Court of PA, please add us to your "safe recipients" list in your email system. Please do not reply to this email. Send any comments or questions to [email protected]. Guidance on Social, Political Activities of Judges and Candidates Issued The past month saw the publication of two items which should provide guidance to judicial officials and candidates. The Ethics Committee of the Pennsylvania Conference of State Trial Judges published Formal Opinion 2014-1, addressing the propriety of various social activities of judges. The opinion provides lists of social activities deemed acceptable in three categories: those involving attorneys, law firms and attorney associations; those sponsored by charitable organizations; and other activities such as inaugurations, symposia, and seminars. The opinion identifies ten questions a judge should ask regarding any proposed engagement: 1. Is the event intended to improve the law, the legal system, or the administration of justice, or is it purely a social function? 2. -

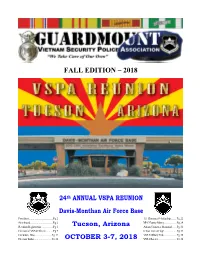

2018 Fall Edition Gm By

FALL EDITION – 2018 24th ANNUAL VSPA REUNION Davis-Monthan Air Force Base President .................................... Pg 2 J.J. Chestnut Scholarship ........ Pg 22 Sisterhood .................................. Pg 2 MPC-Funny Money .................. Pg 24 Reunion Registration ................. Pg 3 Tucson, Arizona Adrian Cronauer Memorial ...... Pg 32 Election of VSPA Officers .......... Pg 9 It Was Just A Flag! .................. Pg 33 Candidate Bios ......................... Pg 12 VSPA Military Pride ................. Pg 35 Election Ballot .......................... Pg 20 OCTOBER 3-7, 2018 VSPA Roster ........................... Pg 38 PRESIDENT’S CORNER Greg Cain, Life Member #62, Binh Thuy – 67-68 My Brothers and Sisters, We are looking forward to our reunion in Tucson, AZ at Davis Monthan AFB in October. Sheila and I had a wonderful meeting in February with Bill and Janice Cummings who are Tucson area residents and did the groundwork for site selection. We visited the Desert Diamond Casino/Hotel complex next to the airport. The facility far exceeded our expectations by miles when compared to other not so nice selections. The staff was very cordial and professional and catered to all our requirements. They are very experienced in Veteran reunions and met our needs remarkably well. Expect a most excellent time! You can find specific information about the site by going to their website at www.ddcaz.com. Please bring any informational items you wish to present or have presented to our members during the business meeting and we will make a spot for you on the agenda (Sisterhood too). This would include health updates, new potential events and personnel. This past ugly winter was as bad as it gets. -

Former Roanoke Disc Jockey Adrian Cronauer, Depicted in “Good Morning, Vietnam,” Dies at 79 | Local News | Roanoke.Com

7/19/2018 Former Roanoke disc jockey Adrian Cronauer, depicted in “Good Morning, Vietnam,” dies at 79 | Local News | roanoke.com https://www.roanoke.com/news/local/former-roanoke-disc-jockey-adrian-cronauer-depicted-in-good- morning/article_e525841b-84dc-58b1-8160-8ca8cb7cda84.html Former Roanoke disc jockey Adrian Cronauer, depicted in “Good Morning, Vietnam,” dies at 79 By Henri Gendreau [email protected] 540-981-3227 7 hrs ago Adrian Cronauer moved to Troutville in 2009. The Roanoke Times | File https://www.roanoke.com/news/local/former-roanoke-disc-jockey-adrian-cronauer-depicted-in-good-morning/article_e525841b-84dc-58b1-8160-8… 1/5 7/19/2018 Former Roanoke disc jockey Adrian Cronauer, depicted in “Good Morning, Vietnam,” dies at 79 | Local News | roanoke.com Keynote speaker Adrian Cronauer (left) and Vietnam Vet John Inge honor the memorial while taps is Buy Now being played at The Wall That Heals, a 250-foot-long replica of the wall in Washington, D.C., at the Salem Veterans Aairs Medical Center for ve days to honor those who made the ultimate sacrice. About 100 names on the wall are from the Roanoke and New River Valleys. Don Petersen |Special to The Roanoke Times Adrian Cronauer, a disc jockey, actor and Pentagon adviser whose story as a radio host during the Vietnam War inspired the 1987 lm “Good Morning, Vietnam,” helping make its star Robin Williams a household name, died Wednesday in Troutville. He was 79. His death was conrmed by Je Hunt, a longtime Roanoke radio announcer who hired Cronauer at Roanoke FM station WPVR. -

G6600 Good Morning, Vietnam (Usa, 1987)

G6600 GOOD MORNING, VIETNAM (USA, 1987) Credits: director, Barry Levinson ; writer, Mitch Markowitz. Cast: Robin Williams, Forest Whitaker, Tung Thanh Tran. Summary: War/comedy set in and around Saigon in the 1960s based on the true story of Adrian Cronauer. Cronauer (Williams) is an irreverent, nonconformist Air Force enlisted man who works as a disc jockey on Armed-Forces Radio in Saigon early in the Vietnam War. Imported by the Army to host an early morning radio show, Cronauer blasts the formerly staid, sanitized airwaves with a constant barrage of rapid-fire humor and the hottest hits from back home. The G.I.’s love him, but the brass is up in arms. Adair, Gilbert. Hollywood’s Vietnam [GB] (p. 4, 210) Alion, Yves. “Good morning, Vietnam” Revue du cinema hors ser. 35 (1988), p. 50- 51. Althen, Michael. “Baseball, Bonanza, Baltimore” Steadycam n. 10 (spring 1988), p. ? Auster, Al and Quart, Leonard. How the war was remembered: Hollywood & Vietnam [GB] (p. 147) Baxter, Brian (see under Lewis, Brent) Bernikow, Louise. “The right role at last” Premier 1 (Jan 1988), p. 38-41. “A Big ‘Good morning, Vietnam’” Philadelphia inquirer (Jan 20, 1988), p. E8. Boyum, Joy Gould. [Good morning, Vietnam] Glamour 86 (Mar 1988), p. 253. Buchka, Peter. “Die grosste Kanone von Da-Da-Da-Nang” Suddeutsche Zeitung (Sep 10, 1988), p. ? “Can Disney film make us laugh about Vietnam?” Miami herald (Jun 7, 1987), p. 5K. Canby, Vincent. “Film: ‘Good morning, Vietnam’” New York times 137 (Dec 23, 1987), p. C11. Carr, Jay. “Making ‘M*A*S*H’ seem tame” Boston globe (Jan 15, 1988), Living, p. -

September 2018 NOTEFROMPRESIDENTDAVE

September 2018 N O T E F R O M P R E S I D E N T D A V E Greetings to All!!! August was a good month for AHRS!!! All meetings were well attended. All work stations in the shop continue to be active. Progress is being made in getting items in the shop repaired and back to the owners. The shop committee is making progress in identifying items that have no paper work. Our procedure for taking in items for repair or for donation is improving. If you take in any item, be sure all necessary information is on the paper work. We need full names, addresses and contact information. The August business meeting on the 27th was one of the best attended that I can remember!!! The excellent program on the National Company presented by Dave Cisco and Joe Veras really brought the people out!!! The program was videotaped with the assistance of Ed Boutwell, and we hope to have it on YouTube and the AHRS website shortly. Upgrading of our various displays is continuing. We are waiting for an enclosure to place the search light radio in the Alabama Power Company atrium. We may have to rearrange the current limited display area to make room, but I believe the result will be worth the effort. The reset of the displays in the shop continues. Now that John Outland is back from his Alaska Adventure, we will move into Phase #2 of the project, the rearranging and organizing the broadcast radio and television area and the novelty radio cases. -

Good Morning, Vietnam

Commentary by Don Kunz Barry Levinson’s Good Morning, Vietnam arry Levinson’s Good Morning, Vietnam (Touchstone Pictures, 1987) is an oddity among Vietnam War films. Unlike most Hollywood treatments of that war, it focus- es attention on REMFs B(rear-echelon motherfuckers) rather than grunts. And, although based loosely on airman Adrian Cronauer’s tour of duty as an Armed Forces Radio Disc Jockey in Saigon in 1965 and 1966, it nevertheless largely decontextualizes the war from specific historical events. At the same time, despite being produced at the end of the 1980s, it shuns the Reagan era’s rewriting of the war as a cartoonish revenge scenario in which Americans fight and win a rematch against the North Vietnamese. But most peculiarly, it is a comedy. As a result of departing from expectations created by its subject matter, production era, and ostensible genre, critical assessments of the film have been sharply divided. William Palmer dismissed Good Morning, Vietnam as a “shallow, plotless combination of a Robin Williams comedy concert and an extended music video masquerading as a biopic” (Gilman 235). And Henry A. Giroux denigrated it as a Disney inspired slapstick version of the war which is sexist, racist, and colonialist in its representations (51-56). But Owen W. Gilman, Jr. celebrated it as an improvisational text whose form brilliantly mirrors the insanity and chaos of American involvement in Vietnam (242). Whatever the critical opinion of Good Morning, Vietnam, it was Barry Levinson’s most lucrative work to date, earning $125 million (Greenburg 136), and it revived Robin William’s flagging movie career with a Best Actor Academy Award nomination and a Golden Globe award for his performance as Adrian Cronauer (Dougan 119, 133-34). -

Racism at the Movies: Vietnam War Films, 1968-2002 Sara Pike University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2008 Racism at the Movies: Vietnam War Films, 1968-2002 Sara Pike University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Pike, Sara, "Racism at the Movies: Vietnam War Films, 1968-2002" (2008). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 181. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/181 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACISM AT THE MOVIES: VIETNAM WAR FILMS, 1968-2002 A Thesis Presented by Sara L. Pike to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2008 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: Advisor - Chairperson HyyMurphree, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of Graduate Studies Date: March 25,2008 Abstract Films are a reflection of their time, and portrayals of the Vietnamese in film are reflective of the attitudes of American culture and society toward Vietnamese people. Films are particularly important because for many viewers, all they know about Vietnam and the Vietnamese is what they have seen on screen. This is why it is so important to examine the racist portrayals of the Vietnamese that have been presented, where they come from, and how and why they have changed.